CHAPTER REVIEW

FACTS AND TOOLS

Question 22.7

1. This chapter had four big lessons. Each of the following situations illustrates one and (we think) only one of those lessons. Which one?

Militaries throughout the world give medals, citations, and other public honors to members of the military who excel in their duties.

People tip for good service after their meal is concluded.

Real estate agents work on commission, but office managers at a real estate office are paid a straight salary.

In Pennsylvania in 2009, two judges received $2.6 million in bribes from a juvenile prison. The more people they sent to jail, the more they received from the prison owners. What tipped off prosecutors was that the judges were sentencing teens to such harsh sentences for relatively minor crimes. One teenager was sent to prison for putting up a Facebook page that said mean things about her school principal; another accidentally bought a stolen bicycle. (Both judges pled guilty.)

Studies have shown that when employers initially enroll all workers in a retirement plan, the workers save more than when they must ask to join the retirement plan, even when in both cases workers can quit or join the plan at any time.

Question 22.8

2. An American church sends 10 missionaries to Panama for three years to find new converts. Every six months, the missionary with the most new converts gets to be the supervising missionary for the next six months. This basically means that he or she gets to drive a car, while the other nine have to walk or ride bicycles. Clearly, this is a tournament. Now consider the following two cases. For which case will the church’s incentive plan work better? (Hint: Think about ability risk vs. environment risk.)

Case 1: Missionaries specialize in different regions: Some stay in rich neighborhoods for the whole six months, others stay in poor neighborhoods for the whole six months.

Case 2: Missionaries move from region to region every few weeks, so that all missionaries spend a little time in every kind of Panamanian neighborhood.

Question 22.9

3. Clever marketers understand choice architecture. Why are clearance racks in clothing stores usually located in the back of the store rather than in the front?

Question 22.10

4. The basketball player Tim Hardaway was once promised a big bonus if he made a lot of assists. Can you think of any problems that such an incentive scheme might cause? Many professional athletes get a bonus if they win a championship. Is this kind of incentive better or worse than a basketball player’s bonus for assists? Why?

Question 22.11

5. Let’s return to Big Idea Four (thinking on the margin) back in Chapter 1. Why are calls to give harsher penalties to drug dealers and kidnappers often met with warnings by economists?

Question 22.12

6. Why are salespeople so much more likely than other kinds of workers to be paid on a “piece rate” (i.e., on commission)? What is it about the kind of work they do that makes the high-commission + low-base-salary combination the equilibrium outcome?

Question 22.13

7. Unlike in the previous question, sometimes piece rates don’t work so well. Why might the following incentive mechanisms turn out to be more trouble than they’re worth?

An industrial materials company pays welders by the number of welds per hour. Of course, the company pays only for necessary welds.

424

A magazine publisher pays its authors to write “serial novels” one chapter at a time. The authors are paid by the word (common in the nineteenth century and how Dickens and Dostoyevsky made their livings).

Question 22.14

8. The typical corporate executive’s incentive package offers higher pay when the company’s stock does well. One proposal for such executive merit pay is to instead pay executives based on whether their firm’s stock price does better or worse than the stock price of the average firm in their own industry. Does this proposal solve an environment risk problem or an ability risk problem? How can you tell?

THINKING AND PROBLEM SOLVING

Question 22.15

1. In 1975, economist Sam Peltzman published a study of the effects of recent safety regulations for automobiles. His results were surprising: Increased safety standards for automobiles had no measurable effect on passenger fatalities. Pedestrian fatalities in automobile accidents, however, increased. (This is now known as the Peltzman effect and has been tested repeatedly over the decades.)

Why might more pedestrians be killed when a car has more safety features?

Economists have looked for ways out of Peltzman’s dilemma. Here’s one possible solution: Gordon Tullock, our colleague at George Mason, has argued that cars could have long spikes jutting out of the steering column pointed directly at the driver’s heart. Keeping Peltzman’s paper and the role of incentives in mind, would you expect this safety mechanism to result in an increase, decrease, or no change in automobile accident fatalities? Why?

Would a pedestrian who never drives or rides in cars tend to favor Tullock’s solution? Why or why not?

Question 22.16

2. One reason it’s difficult for a manager to set up good incentives is because it’s easy for employees to lie about how they’ll respond to incentives. For example, Simple Books pays Mary Sue to proofread chapters of new books. After an author writes a draft of a book, Simple sends chapters out to proofreaders like Mary Sue to make sure that spelling, punctuation, and basic facts are correct.

As you can imagine, some books are easy to proofread (perhaps Westerns and romances), while others are hard to proofread (perhaps engineering textbooks). But what’s difficult or easy is often in the eye of the beholder: Simple can’t tell which books are particularly easy for Mary Sue to proof, so they have to take her word for it. Let’s see how this fact influences the publishing industry.

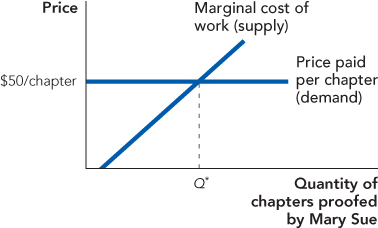

In the following figure, Q* is the number of chapters in the new book Burned: The Secret History of Toast. It’s a strange mix of chemistry and history, so Simple isn’t sure how Mary Sue will feel about proofing it. The marginal cost curve shows Mary Sue’s true willingness to work: The more chapters she has to read, the more you have to pay her. If Simple offers to pay her $50 per chapter, as shown, she’ll actually finish the job.

If Mary Sue wants to bluff, claiming that the book is actually painful to read, what is that equivalent to?

Supply curve shifting left

Supply curve shifting right

Demand curve shifting down

Demand curve shifting up

Once you decide, make the appropriate shift in the figure.

The publisher just has to have Mary Sue proof all Q* chapters of Burned: All its other proofreaders are busy. The publisher will pay what it needs to for her to finish the book. This is the same as another curve shift in a certain direction: Draw in this shift in the figure.

425

What did Mary Sue’s complaining do to her price per chapter? What did it do to her work load?

(Bonus) You’ve seen how Mary Sue’s bluffing influenced the outcome. What are some things that Simple might do to keep this from happening?

Question 22.17

3. Who do you think is in favor of forbidding baseball player contracts from including bonuses based on playing skill? Owners or players? Why?

Question 22.18

4. In the short, readable classic Congress: The Electoral Connection, David Mayhew uses the basic ideas of incentives and information as a pair of lenses through which to view members of Congress. What he saw was quite simple: The urge for reelection drives everything. Thus, members are driven by self-interest to give the voters in their home district as much as possible. Of course, voters face the same problem in judging members of Congress that any manager faces when evaluating an employee: Some outputs are harder to measure than others, so voters focus on measurable outputs. With that in mind, what will voters be most likely to care about? Choose one from each pair and briefly explain why you made that choice.

How many dollars come to the district for new hospitals and highways vs. how many dollars are spent on top-secret military research.

How well the member behaved in private meetings with Chinese leaders vs. how the member sounded on Meet the Press.

How well the member did in reforming the Justice Department vs. how well the member did at the Turkey Toss back in the district last Thanksgiving.

(As you’ve seen, voters’ focus on the visible can easily drive the member’s entire career. Mayhew’s book was an important early work in “public choice,” the use of basic microeconomic ideas like self-interest and strategy to study political behavior. For more on the topic, Kenneth Shepsle and Mark Bonchek’s short textbook Analyzing Politics is highly recommended. See also Chapter 20 of this textbook.)

Question 22.19

5. In the movie business, character actors are typically paid a fixed fee, while movie “stars” are typically paid a share of the box office revenues. Why the difference? Try to give two explanations based on the ideas in this chapter.

Question 22.20

6. Let’s return to the question we posed in the chapter: Suppose that the big environment risk is not bad professors but rather hard material. Imagine, for example, that some classes are more difficult than other classes (quantum physics 101 vs. handball 101). If you really wanted to learn a little about quantum physics but you were afraid of reducing your GPA, you’d face a tough choice. A curve is better for you than an absolute scale, but even if your professor grades on a curve, you’re probably still sitting in a class with other well-trained physics majors. Let’s see if we can find a work-around.

At your school, are there certain times of the day when the less serious, more fun-loving tend to take their classes? If so, what time is that? If you sign up for a section scheduled then, you might look better on the curve.

Some schools offer simplified (we won’t say “dumbed down”) versions of some hard courses. Does your school offer anything like this? If so, does it allow majors to take the same sections as the nonmajors? How is this sorting related to tournament theory?

If you were a professor, which teaching schedule would you rather have: two sections where the majors and nonmajors are mixed together, or one section with the majors and one with the nonmajors?

Question 22.21

7. When an accused defendant is brought before a judge to schedule a trial, the judge may release the defendant on his or her “own recognizance” or the judge may demand that the defendant post bail, an amount of cash that the defendant must give to the court and that will be forfeited if the defendant fails to appear. Many defendants don’t have the cash, so they borrow the money from a bail bondsperson. So if the defendant fails to appear, the bail bondsperson is out the money, unless the defendant is recaptured within 90–180 days. To recover their money, a bail bondsperson will hire bail enforcement agents, also known as bounty hunters, to track down the missing defendant. If the bounty hunters don’t find the defendant, they don’t get paid.

426

If defendants released on their own recognizance fail to appear, they are pursued by the police, but if they are released on bail borrowed from a bondsperson and they fail to appear, they will be pursued by bounty hunters. Which type of defendant do you think is more likely to fail to appear, and which type is more likely to be recaptured if they do fail to appear? Why?

Perhaps surprisingly, bounty hunters tend to be quite courteous and respectful even to defendants who have tried to skip town. Can you think of one reason why?

Question 22.22

8.

Why do so many charitable activities like marathons, walks, and 5K runs give the participants “free” T-shirts, wristbands, hats, bumper stickers, and so forth?

Charitable organizations could probably make a lot of money for their cause by selling these items on their Web sites, but you usually have to actually attend the “2015 Cancer Run” to get the “2015 Cancer Run” T-shirt. Why?

Question 22.23

9. Waiters and waitresses are generally paid very low hourly wages and receive most of their compensation from customer tips.

As the owner of a restaurant, what do you want from your wait staff?

Which element of a waiter’s or waitress’s compensation—the hourly wage or the tips—represents a method of “tying pay to performance”?

Which element of a waiter’s or waitress’s compensation—the hourly wage or the tips—plays the role of “insurance” that the restaurant owner provides for the wait staff? Against what are the waiters and waitresses being insured?

Theoretically, a restaurant owner could pay workers a higher wage, raise menu prices, and make the restaurant strictly tip-free. Or, the owner could eliminate the wage, reduce menu prices, and encourage greater tipping by alerting customers to the fact that the wait staff do not earn an hourly wage. What are the potential pros and cons (from the point of view of the restaurant owner) of each system?

Question 22.24

10. In early 2004, Donald Trump took the idea of using a tournament for hiring executives to a whole new level with the premiere of the TV show The Apprentice. On the show, a group of contestants compete for a position running one of Trump’s many companies for a starting annual salary of $250,000. Generally speaking, on each episode, the contestants are divided up into teams and compete to most successfully complete some business-related task, and a member of the losing team is eliminated.

Contestants for The Apprentice are carefully auditioned and screened, to make sure that each contestant has the skills necessary to do well on the show. Why do you think this screening is done? What kind of risk is being eliminated by this audition process? What would happen if there was one contestant who, right from the beginning, demonstrated more potential and greater capabilities than the other contestants?

Though only one contestant will end up with the job at the conclusion of the show, each must try to prove his or her worth to Trump by performing well in the team challenges. What impact do you think the tournament structure of this “ultimate job interview” has on these team challenges?

Some of the challenges can be quite demanding, and the contestants often work very hard. Wouldn’t it be easier if they all shirked the challenge rather than working hard? Trump would still (presumably) have to choose one of them as the winner—and chances are it would be the same person whether everybody worked hard or not. Why are the contestants not likely to all agree to stop trying so hard?

427

Question 22.25

11. Suppose a CEO wanted more of her employees to get flu shots. How many of the four big lessons in this chapter can you employ to come up with different solutions? (Don’t worry if they’re not all feasible or practical—that’s the reason there are four big lessons in this chapter, not just one.)

Question 22.26

12. A growing anticorruption campaign in India has a clever new tool: a zero-rupee note. The impressive note looks just like a 50-rupee note, but is clearly marked as being worthless and contains anticorruption messages. Indians are encouraged to give these notes to public officials who demand or expect bribes. Over 2.5 million of the notes have been distributed since 2007. A Twitter user tweeted economist Richard Thaler (of Nudge fame) to ask whether this counted as a nudge. What do you think his answer was, and why?

Question 22.27

13. Researchers seem to have a lot of fun testing different nudges to see how well they work. In one experiment, they placed mirrors in shopping carts so customers at a grocery store were forced to look at themselves while they shopped. How would you expect this kind of nudge would impact shoppers’ behavior? (PS: It worked!)

CHALLENGES

Question 22.28

1. Let’s tie together this chapter’s story on incentives with Chapter 15’s story about cartels. Suppose your economics professor grades on a curve: The average score on each test becomes a B–. If all of the students in your class form a conspiracy to cut back on studying, point out how this cartel might break down just like OPEC’s cartel breaks down during some decades.

Question 22.29

2. What type of systems in the United States help overcome the incentives of physicians to order medically unnecessary tests?

Question 22.30

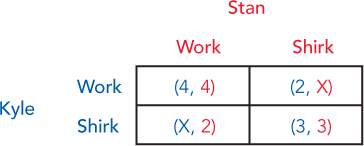

3. In his path-breaking book Managerial Dilemmas, political scientist Gary Miller says that a good corporate culture is one that gets workers to work together even when they face prisoner’s dilemmas (we discussed the prisoner’s dilemma in detail in Chapter 15). In a healthy corporate culture, you feel guilty if you’re being lazy while your buddy is working. Let’s sum up “guilt” as simply as possible: It’s some number “X” that represents how you feel. These figures are adapted from Figure 15.4.

What does X have to be in order to keep this from being a prisoner’s dilemma? Answer with a range (e.g., greater than 12.5, less than −2).

Now, there are two Nash equilibria in this problem. What are they? Using the language of Chapter 15 and Chapter 16, what kind of game has this just become?

There’s an idea buried in the questions from Chapter 16 that will “point” Stan and Kyle toward the best possible outcome. What is it? (Keep in mind that a good corporate culture can help with this part, too.)

Question 22.31

4.

Many HMOs pay their doctors based, in part, on how many patients the doctor sees in a day. What problems does this incentive system create?

If HMOs pay their doctors a fixed salary, what problems does this incentive system create?

Ideally, we would like to pay doctors based on how long their patients live! What problems exist in implementing this type of system?

Question 22.32

5. In most big cities, taxicab fares are fairly standardized, and they are regulated by local governments. For the sake of simplicity, assume that a cab driver works for a licensed taxicab company, and he or she pays a fixed daily fee for the use of the taxi; all fares and tips go to the driver.

In Atlanta, Georgia, meter rates are $2.50 for the first 1/8 mile and $0.25 for each additional 1/8 mile. What are the benefits of allowing cab drivers to charge fares based on the number of miles driven? In other words, what good behavior is encouraged—or what bad behavior is discouraged—by this? What are the possible drawbacks?

428

In addition to the meter rates, there is a $21 per hour waiting fee. Why do you think there is a waiting fee? If cab drivers could not charge a waiting fee, how might that change their behavior? What if cab drivers were always just paid an hourly wage of $21 per hour? What would be the benefits and drawbacks of this payment scheme?

For some fairly standard trips in Atlanta, there are flat fees. A trip from the airport to anywhere downtown, for example, is always $30 (plus $2 for each additional person). What are the potential benefits and drawbacks of this kind of compensation scheme? Why might a city require this payment scheme for trips from the airport?

In the chapter, we talked about the importance of the gap between what you pay for and what you want. What is it that Atlanta’s City Council and taxi customers want from the cab drivers in Atlanta? Which basis for cab fares (miles, hours, trips) comes closest to closing the gap between what is wanted and what is paid for?

!launch! WORK IT OUT

Punishments can be an incentive, not just rewards. Consider an assembly line. Why wouldn’t you necessarily want to reward the fastest worker on the assembly line? What other incentive system might work?