Applications of Supply Elasticity

Let’s examine two important issues in public policy, gun buybacks and slave redemption. In both cases, understanding the elasticity of supply is critical if we are to evaluate these policies wisely.

80

Gun Buyback Programs

The police in Washington, D.C., bought over 6,000 guns, no questions asked, from anyone coming to one of their gun buybacks held between August 1999 and December 2000. The program got a big assist from then President Clinton and the Department of Housing and Urban Development, which paid most of the buyback’s $528,000 cost. Millions of dollars more were spent buying guns in Chicago, Sacramento, Seattle, and dozens of other cities around the country.5

The theory of gun buybacks is that gun buybacks (1) reduce the number of guns in circulation and (2) reductions in the number of guns in circulation reduces crime. It’s not obvious that point (2) is true—guns are used for self-defense as well as for crime so fewer guns could mean more crime. But we don’t have to decide that controversial question here because simple economic theory suggests that point (1) is false—gun buybacks in a city like Washington, D.C., are unlikely to reduce the number of guns in circulation. Let’s see why.

We can analyze the effect of this program with a few questions. What kinds of guns are most likely to be sold at the gun buyback, high-quality or low-quality guns? And, what is the elasticity of supply of such guns to a city like Washington, D.C.?

The best gun to sell at a buyback is one that you can’t sell anywhere else, so buybacks attract low-quality guns. In one Seattle buyback, 17% of the guns turned in didn’t even fire.6

Now here is the key question: What is the elasticity of supply of low-quality guns to a city like Washington, D.C.? Recall from Table 5.3 that local supply curves are typically more elastic than global or national supply curves. It’s estimated that there are 200 to 300 million guns in the United States so there are plenty of low-quality guns—so many that the supply of such guns to Washington, D.C., will be very elastic—elastic enough to make perfectly elastic a good working assumption.

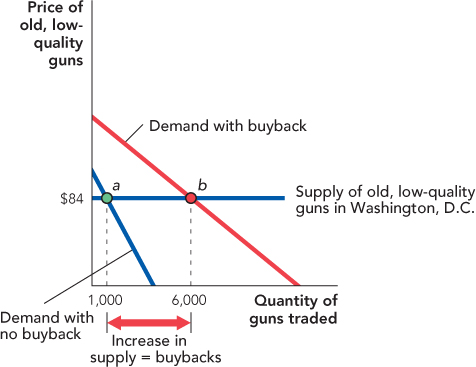

Now that we know that the supply of low-quality guns to Washington, D.C., is very elastic, let’s draw the diagram and analyze the policy. In Figure 5.8, we draw a perfectly elastic supply curve. With no buyback, the price of a low-quality, used gun is $84 and 1,000 guns are traded in Washington. The gun buyback program increases the demand for used guns, shifting the demand curve outward, and the increase in demand pushes up the quantity of guns supplied in Washington, D.C., to 6,000 units. But the supply is so elastic that the price of guns doesn’t increase, so even though the police buy 5,000 guns, the quantity of guns traded on the streets stays at 1,000. In other words, there is no net change in the number of guns on the streets of D.C.

If this seems difficult to believe, imagine that instead of guns, the Washington police decided to buy back shoes. Remember, the idea of a gun buyback is to reduce the number of guns in Washington, D.C. Now, do you think that a shoe buyback would reduce the number of shoes in Washington, D.C.? Of course not. What will happen? People will sell their old shoes, the ones they don’t wear anymore. Some enterprising individuals might even buy old shoes from thrift shops and sell those to the police. (In one Oakland gun buyback, some enterprising gun dealers from Reno, Nevada, drove to Oakland and sold the police more than 50 low-quality guns.7) The shoe buyback is unlikely to cause people to go shoeless, and for the same reasons a gun buyback is unlikely to cause people to go gunless.

81

The key point is that if the police can’t drive up the price of guns, then they can’t reduce the quantity of guns demanded on the streets. And the price of guns is determined not in Washington, D.C., but in the national market for guns where millions of guns are bought and sold so a police buyback of 5,000 guns is too small to influence the price.

It’s even possible that gun buybacks will increase the number of guns in circulation. Suppose that gun buybacks become a common and permanent feature of the market for guns. Before the gun buyback, a purchaser of a new gun expects that it will eventually wear out or otherwise fall in value until it becomes worthless. But when gun buybacks are common, someone buying a gun knows that if it stops working, he can always sell it to the government. A buyback makes new guns more valuable; now they come with an insurance policy protecting against declines in value, which increases the demand for new guns.8 You have probably experienced the same effect—students are more willing to buy an expensive textbook if they know they can easily sell it at the end of the semester—but do keep this book forever!

Given the economic analysis, it’s not surprising that studies of gun buybacks have shown them to be ineffective at reducing crime.9

The Economics of Slave Redemption

Let’s return to our opening example. Recall that Harvard sophomore Jay Williams flew to the Sudan in fall 2000 to buy the freedom of people who had been enslaved. Working with Christian Solidarity International, Williams was able to buy and free 4,000 people. Donations came from all over the United States, including a fourth-grade class in Denver.10

Elasticity and Slave Redemption

http://qrs.ly/284ax6k

The policy of slave redemption has been controversial. Some groups such as Christian Freedom International, equally as humanitarian as Christian Solidarity International, have argued that slave redemption can make a bad situation even worse. Perhaps surprisingly, at the heart of the controversy is the concept of the elasticity of supply. If groups who pay to free people from slavery increase the demand for slaves, what effect will this have on the price of slaves and on the incentives of those who traffic in people?

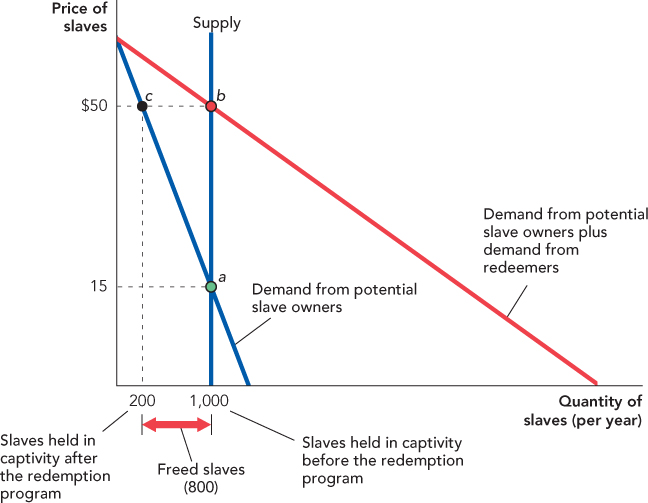

In Figure 5.9, we show the best case for slave redemption, when the supply curve is perfectly inelastic (vertical). When the supply curve is perfectly inelastic, there is a fixed number of slaves no matter what the price. As a result, every person ransomed and freed is one less slave held in captivity. This may be the case that people like Jay Williams were implicitly thinking of when they flew to the Sudan.

In the initial equilibrium at point a, potential slave owners purchase 1,000 slaves at a price of $15. The increase in demand from the redeemers pushes up the price of slaves to $50 at point b. At the higher price, the quantity of slaves demanded by potential slave owners is just 200, so the redeemers are able to free 800 slaves. Since there is no increase in the quantity supplied, every slave purchased is a slave freed.

82

Let’s take a closer look at Figure 5.9. Before the slave redemption program begins, the price of a slave is $15, a realistic number for slaves in Sudan, and there are 1,000 slaves bought and held in captivity every year (point a). With the redemption program, the demand for slaves increases (shifts outward), which pushes the price of slaves up to $50 (point b). Now here is the key: At a price of $50, the quantity of slaves demanded by potential slave owners decreases to 200 (point c). The remaining 800 slaves are bought and freed by the redeemers. Because there is no increase in the quantity supplied in this case, every slave purchased means one less person held in slavery. Note that slave redemption works by driving up the price of slaves so high that potential owners cannot afford to buy slaves. In other words, to work well, slave redeemers must outbid potential slave owners.

Unfortunately, the supply of slaves is unlikely to be perfectly inelastic. We return to one of the primary lessons of this book, incentives. When people enter the market to buy back slaves and increase the price of slaves, they increase the incentive to capture more slaves.

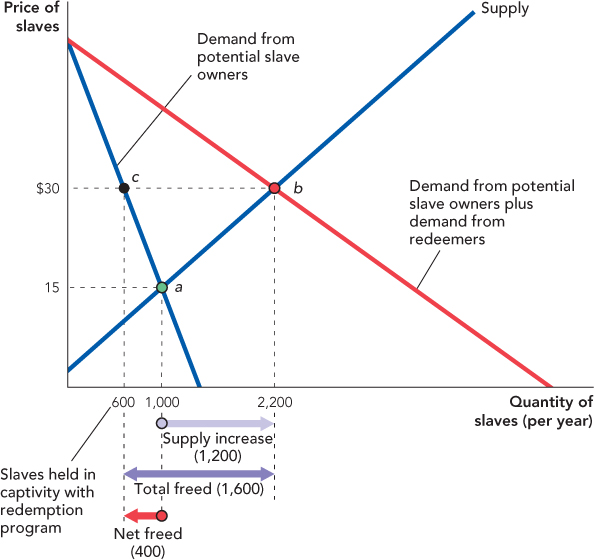

Figure 5.10 analyzes the more realistic case when the supply curve is not perfectly inelastic. In the initial equilibrium, the price of slaves is $15 and potential owners buy 1,000 slaves (point a). When the redeemers enter the market, the demand for slaves increases and the price increases from $15 to $30 (point b). The price of slaves does not increase as much as when the supply curve was perfectly inelastic because some of the increased demand for slaves is met by a greater quantity supplied. At a price of $30, the quantity of slaves demanded by potential owners falls from 1,000 to 600 (point c), but notice also that the total number of people captured by traffickers increases by 1,200 to 2,200 (point b). Of these 2,200, 1,600 are freed by the redeemers, leaving 600 held in captivity.

83

Let’s summarize: Before redemption, 1,000 slaves were demanded by slave owners. After redemption, demand has dropped to 600 slaves from these slave owners. This is the good result of the redemption program. But due to the higher price of slaves, slave traffickers increase the quantity of slaves from 1,000 to 2,200. The redeemers free 1,600 of these 2,200 slaves, but 1,200 of these would not have been enslaved had it not been for the increase in demand. Thus, on net, the slave redeemers free just 400 slaves.

The key point is this: The additional demand for slaves from those who wish to free slaves pushes up the price of slaves, which reduces the quantity demanded—that’s good. But the higher price also pushes up the quantity supplied—that’s bad.

Thus, slavery redemption programs create a true dilemma. The groups that buy freedom can reduce the number of slaves held in captivity, but only at the price of increasing the number of people who are enslaved for at least some time. An economist can point to this dilemma, but economics does not offer a solution (and unfortunately neither does anyone else).

Is there any evidence on the effect of slave redemption programs? Remember that one sign of whether the redemption program is working is how much the program increases the price of slaves. Higher prices mean that the redeemers are outbidding potential slave traffickers. Data on slave prices in the Sudan are unreliable, but the fragmentary data that do exist are not encouraging. Although the redemption program initially appeared to raise prices, prices soon began to fall.11 Recall that supply tends to be more elastic in the long run—thus, the data on prices are consistent with a supply curve that became more elastic over time. Since redemption programs are less effective when the elasticity of supply is greater, the data on prices suggest that the program became less effective over time.

84

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 5.4

A computer manufacturer makes an experimental computer chip that critics praise, leading to a huge increase in the demand for the chip. How elastic is supply in the short run? What about the long run?

A computer manufacturer makes an experimental computer chip that critics praise, leading to a huge increase in the demand for the chip. How elastic is supply in the short run? What about the long run?

Question 5.5

Will the same increase in the demand for housing increase prices more in Manhattan or in Des Moines, Iowa?

Will the same increase in the demand for housing increase prices more in Manhattan or in Des Moines, Iowa?

Finally, let us note some further complications. Slavery in the Sudan is part of a larger civil war—the government in Khartoum permits and even encourages slave traffickers who attack the government’s enemies. When redeemer groups buy slaves, they are funding not simply slave traffickers but shock troops in a civil war. Guns bought with money received from selling slaves can be used to kill as well as to enslave. Even if we concluded that slave redemption was on average good for the slaves, it might not be good once we account for all of the external effects of enriching slave raiders. (We explain the idea of external effects at greater length in Chapter 10.)

Ultimately, the only way to truly end slavery is to raise the punishment for buying or selling slaves to so high a level that there is no longer a market for slaves. Doing this in the Sudan will require an end to the civil war and the establishment of the rule of law.*