Chapter 1. Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

And finally, a collective thank you to all Psychology students, past,present, and to come, who continue to teach us more than we can ever teach them. Our work is never done.

This Introduction to Psychology project began with a germ of an idea. Two years later, after careful cultivation and creative collaboration, it has become a viable organism, with a name. B110 is now ready to interact with students who are beginning their foray into the scientific study of behavior and mental processes.

John Kremer, on whose shoulders I stand. Gerald Nosich, for lighting and sustaining the flame of critical thinking. Kathy Johnson, for believing in the project and giving it legs. Jane Williams, for maintaining the momentum of the project. Gayle Yamazaki, for seeing the vision before it was clear. Bethany Neal-Beliveau, for tireless editing and fearless championing. Scott Comer, for genius computer programming and being a kind human. Lisa LaRew, for managing the project with supreme patience and skill.

The authors of the eBook have something special in common, and that is their connection to the Department of Psychology at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI). Each author is (or was) on the faculty or received his/her doctoral training in the department. Working with this group of people has been the most gratifying and enjoyable experience of my professional life. They like teaching, they like students,and moreover, they like thinking about how to teach Psychology.

Leslie Ashburn-Nardo, Ph.D., Experimental (Social) Psychology Amy Bracken, Ph.D., Neuroscience Kikuko Campbell, Ph.D., Clinical Psychology, MPH, Public Health Lisa Contino, Ph.D., Clinical Psychology, MS, Education Nicholas Grahame, Ph.D., Behavioral Neuroscience Michele Hansen, Ph.D., Social Psychology Debora S. Herold, Ph.D., Cognitive and Developmental Psychology Shenan Kroupa, Ph.D., Developmental Psychology Jennifer Lydon-Lam, Ph.D., Clinical Psychology Bethany-Neal Beliveau, Ph.D., Pharmacology Kevin L. Rand, Ph.D., Clinical Psychology

Question 1.1

s6tOk2g6wTMMJ74jD2mfaiUlFsNp3q+JKcKZGoYal2MGeWOvAekoeoQY3FPgoV/lNNdRo89HRzRG/3aVSample header with gradient

You are about to embark on an excursion into the science of behavior and the mind. You signed up, without knowing where you were going, how you would get there, or what you would be doing along the way. You may not even know why you signed up. What have you brought with you?Ironically, you’ve brought the very things we will be studying—your own behavior and mental processes, your assumptions about the causes of behavior, your ability to observe the behavior of others, and most importantly, your ability and willingness to observe yourself. So, do you have everything you need? Actually, you do: self, others, the content of Psychology delivered in the course materials, and guides in the form of your instructor, teaching assistant, and peer mentor. Your instructor has been on this trip many times, and therefore, knows what to expect along the way. Let’s go.

You are about to embark on an excursion into the science of behavior and the mind. You signed up, without knowing where you were going, how you would get there, or what you would be doing along the way.

You may know more about Psychology than you think you do. You already know something about behavior because you’ve been engaged in it all your life. Furthermore, you’ve beenobserving it in yourself and others, and that means you’ve begun to think about it, maybe even wonder about it. You may have even tried to understand and solve a psychological problem or two. In doing so, you were acting like a behavioral scientist, a detective of sorts, although you may not have been aware of it at the time. You made observations and gathered information as you developed your own ideas about the reasons people think, feel, and act as they do.

Some more text

1.1 Introduction to Psychology: Thinking Through the Themes

Why and How Do We Study Behavior?

1.2 INTRODUCTION

Critical Thinking Table

Printable Chapter

1.1.1 What Is This Course About?

1.1.2 How Am I Going to Learn Psychology?

1.1.3 Homework

1.2.1 What Is This Course About?

You may know more about Psychology than you think you do. You already know something about behavior because you’ve been engaged in it all your life. Furthermore, you’ve been observing it in yourself and others, and that means you’ve begun to think about it, maybe even wonder about it. You may have even tried to understand and solve a psychological problem or two. In doing so, you were acting like a behavioral scientist, a detective of sorts, although you may not have been aware of it at the time. You made observations and gathered information as you developed your own ideas about the reasons people think, feel, and act as they do.

Students who are new to the study of Psychology are filled with questions.Why do I have to take this course? What does Psychology have to do with other majors and professions, like Biology, Nursing, Business, Education,or Criminal Justice? How are we going to approach Psychology—will we take a macro view or a micro view? Will there be more of an emphasis on how the field developed into what it is today, or will we learn how Psychology applies to everyday life? Is it about how people behave or is it about what brain cells are doing? Many students are interested in the connection between mind and body, such as the effect of nutrition and exercise on mood and wellbeing. Others want to be able to recognize when a person is psychologically unstable, or know more about the causes and solutions to destructive behaviors like violence and alcohol abuse. You may wonder how Psychology is used in advertising, sales, and law enforcement,or if this course will help you be a better person, partner, or parent. In a nutshell, Psychology is about behavior—describing it, explaining it,predicting it, changing it.

Psychology is the scientific study of behavior and mental processes. You are going to study behavior and mental processes in scientific ways.Let’s break that down. Behavior is an observable action emitted by an organism. Mental processes, though more difficult to observe directly,include thoughts, feelings, and beliefs. If our ways of studying something are scientific, they are based on systematic observation, and their goals are to describe, explain, predict, and change. So you know what you will be studying and how you will be studying it—you will come to know the content of the field of Psychology through its systematic, scientific ways of thinking about behavior. Introductory Psychology is just that—a firstexposure to an entire discipline. The goal of this course is to familiarize you with the logic of the discipline of Psychology so that you will begin tothink like a psychologist about anything and everything related to behavior and mental processes. As you develop this skill, you will notice that you are using it and applying it wherever you are in the world.

Take a Moment to Reflect and Write

What do you want to know?

Take a moment now to formulate some questions you have about behavior. Reflect on yourself, then others; people you know well and those you don’t; people who matter the most to you and those who are not as important; people next door and on the other side of the globe; people whose behavior looks a lot like yours and people who are different. What do you want to know? What do you want to get out of this course?

1.2.2 How Am I Going to Learn Psychology?

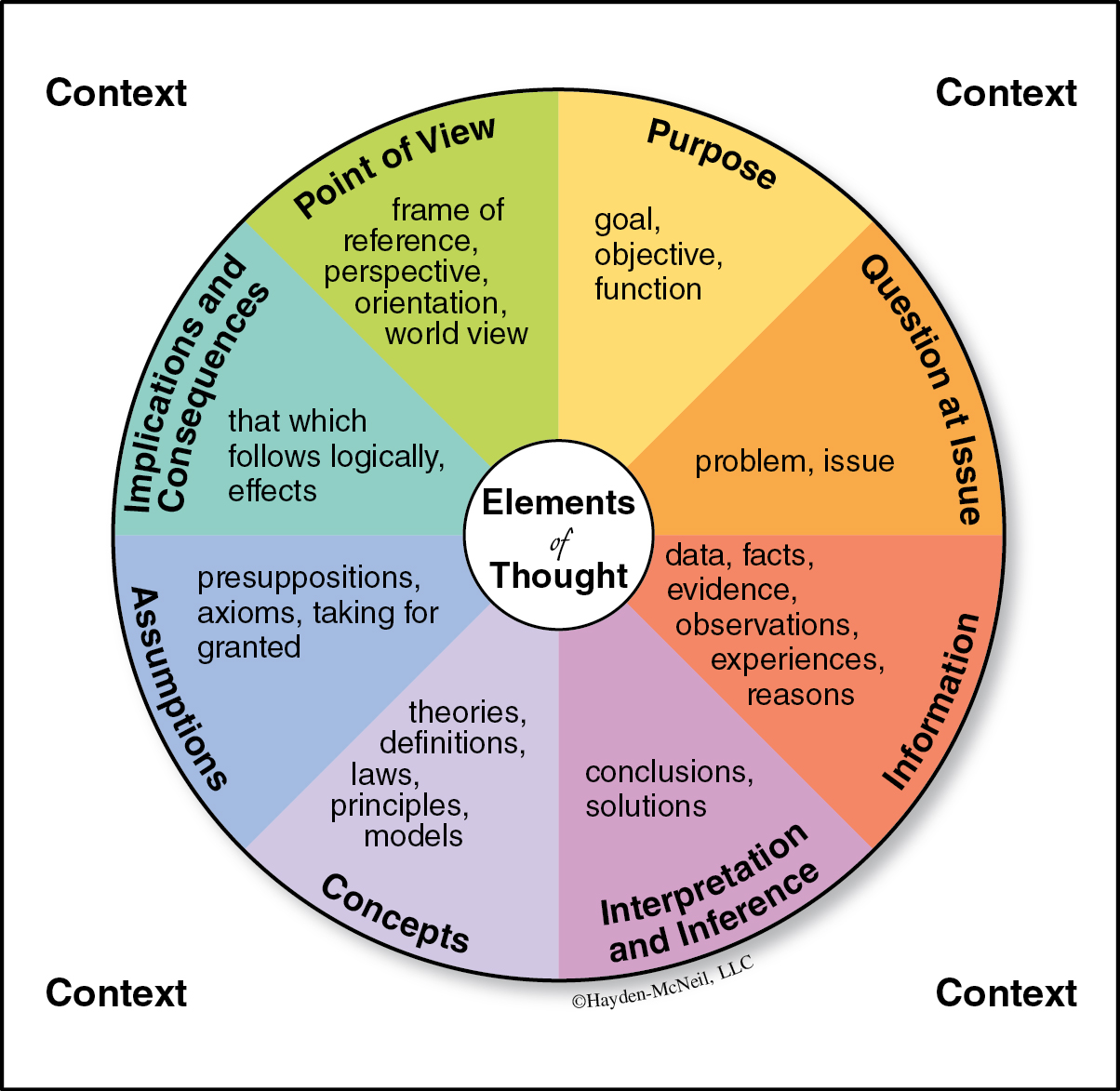

Let’s start with thinking…critically…about anything. You have most certainly heard about critical thinking, as it is often stated as a learning objective in college-level courses. You may even think that the critical thinking you do in your Physics class is not the same critical thinking that you do in your Psychology class.And in a way, you are right.However, I challenge you to broaden your idea of critical thinking, beyond specific courses, even beyond areas of study, to include everything you think about—from the most mundane decisions you make to the weightiest ones. The critical thinking model that we will use in this course is one that allows you to do just that. Developed by Richard Paul and Linda Elder (2006), the model has eight elements of reasoning that, together, capture the essence ofthinking critically- the process of analyzing and assessing thinking with a view to improving it.Let’s analyze the structure of thinking.

For practice, let’s use these elements to think critically about a decision facing many students at some point in their college career—whether or not to stay in school. Although we can start anywhere on the circle, and we don’t have to go in any particular order, let’s start with Purpose. I’ve asked the questions; you answer them. With practice, you’ll ask yourself the questions (and answer them too!).

Critical Thinking: Elements and Questions

The process we just used to think about a real-life, personal issue, is the same process we will use to think about Psychology throughout this course. With deliberate practice, and over time, you can become increasingly aware of your own thinking process, even as it is occurring.The elements of thought are like a dynamic, powerful engine that will move your thinking to another level.