Chapter 1. Sensation and Perception

Introduction to the chapter

Twenty-four hours a day, stimuli from the outside world bombard

your

body. Meanwhile, in a silent, cushioned, inner world, your brain

floats in utter darkness. This raises a question, one that predates

psychology by thousands

of years and helped inspire its beginnings a

little more than a

century ago: How does the world out there get in?

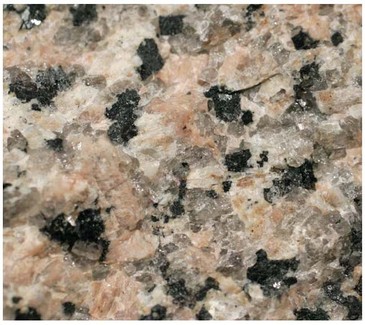

caption line 2

To modernize the question: How do we construct our representations of the external world? How do we represent a campfire's flicker, crackle, and smoky scent as patterns of active neural connections? And how, from this living neurochemistry, do we create our conscious experience of the fire's motion and temperature, its aroma and beauty?

Here's a formula!:

To represent the world in our head, we must detect physical energy from the environment and encode it as neural signals , a process traditionally called sensation . And we must select, organize, and interpret our sensations, a process traditionally called perception. In our everyday experiences, sensation and perception blend into one continuous process. In this chapter, we slow down that process to study its parts.

1.1 Reflections on Two Major Developmental Issues

Sensory systems enable organisms toobtain needed information. Consider:

- A frog, which feeds on flying insects, has eyes with receptor cells that fire only in response to small, dark, moving objects. A frog could starve to death knee-deep in motionless flies. But let one zoom by and the frog's "bug detector" cells snap awake.

- A male silkworm moth has receptors so sensitive to the odor of the female sex-attractant that a single female silkworm moth need release only a billionth of an ounce per second to attract every male silkworm moth within a mile. That is why there continue to be silkworms.

- We are similarly designed to detect what are, for us, the important features of our environments. Our ears are most sensitive to sound frequencies that include human voice consonants and a baby's cry.

Nature's sensory gifts suit each recipient's needs.