Contemporary Psychology

KEY THEME

As psychology has developed as a scientific discipline, the topics it investigates have become progressively more diverse.

KEY QUESTIONS

How do the perspectives in contemporary psychology differ in emphasis and approach?

How do psychiatry and psychology differ, and what are psychology’s major specialty areas?

Over the past half-

10

Major Perspectives in Psychology

Any given topic in contemporary psychology can be approached from a variety of perspectives. Each perspective discussed here represents a different emphasis or point of view that can be taken in studying a particular behavior, topic, or issue. As you’ll see in this section, the influence of the early schools of psychology is apparent in the first four perspectives that characterize contemporary psychology.

THE BIOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE

As we’ve already noted, physiology has played an important role in psychology since it was founded. Today, that influence continues, as is shown by the many psychologists who take the biological perspective. The biological perspective emphasizes studying the physical bases of human and animal behavior, including the nervous system, endocrine system, immune system, and genetics. More specifically, neuroscience refers to the study of the nervous system, especially the brain. Sophisticated brain-

THE PSYCHODYNAMIC PERSPECTIVE

The key ideas and themes of Freud’s landmark theory of psychoanalysis continue to be important among many psychologists, especially those working in the mental health field. As you’ll see in Chapter 10 on personality, and Chapter 14 on therapies, many of Freud’s ideas have been expanded or modified by his followers. Today, psychologists who take the psychodynamic perspective may or may not follow Freud or take a psychoanalytic approach. However, they do tend to emphasize the importance of unconscious influences, early life experiences, and interpersonal relationships in explaining the underlying dynamics of behavior or in treating people with psychological problems.

THE BEHAVIORAL PERSPECTIVE

Watson and Skinner’s contention that psychology should focus on observable behaviors and the fundamental laws of learning is evident today in the behavioral perspective. Contemporary psychologists who take the behavioral perspective continue to study how behavior is acquired or modified by environmental causes. Many psychologists who work in the area of mental health also emphasize the behavioral perspective in explaining and treating psychological disorders. In Chapter 5 on learning, and Chapter 14 on therapies, we’ll discuss different applications of the behavioral perspective.

11

THE HUMANISTIC PERSPECTIVE

The influence of the work of Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow continues to be seen among contemporary psychologists who take the humanistic perspective (Serlin, 2012; Waterman, 2013). The humanistic perspective focuses on the motivation of people to grow psychologically, the influence of interpersonal relationships on a person’s self-

THE POSITIVE PSYCHOLOGY PERSPECTIVE

The humanistic perspective’s emphasis on psychological growth and human potential contributed to the recent emergence of a new perspective. Positive psychology is a field of psychological research and theory focusing on the study of positive emotions and psychological states, positive individual traits, and the social institutions that foster those qualities in individuals and communities (Csikszentmihalyi & Nakamura, 2011; Peterson, 2006; Seligman & others, 2005). By studying the conditions and processes that contribute to the optimal functioning of people, groups, and institutions, positive psychology seeks to counterbalance psychology’s traditional emphasis on psychological problems and disorders (McNulty & Fincham, 2012).

Topics that fall under the umbrella of positive psychology include personal happiness, optimism, creativity, resilience, character strengths, and wisdom. Positive psychology is also focused on developing therapeutic techniques that increase personal well-

THE COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE

During the 1960s, psychology experienced a return to the study of how mental processes influence behavior. Often referred to as “the cognitive revolution” in psychology, this movement represented a break from traditional behaviorism. Cognitive psychology focused once again on the important role of mental processes in how people process and remember information, develop language, solve problems, and think.

The development of the first computers in the 1950s contributed to the cognitive revolution. Computers gave psychologists a new model for conceptualizing human mental processes—

THE CROSS-

More recently, psychologists have taken a closer look at how cultural factors influence patterns of behavior—

12

CULTURE AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR

What Is Cross-

People around the globe share many attributes: We all eat, sleep, form families, seek happiness, and mourn losses. Yet the way in which we express our human qualities can vary considerably among cultures (Triandis, 2005). What we eat, where we sleep, and how we form families, define happiness, and express sadness can differ greatly in different cultures.

Culture refers to the attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors shared by a group of people and communicated from one generation to another (Cohen, 2009, 2010). Studying the differences among cultures and the influences of culture on behavior are the fundamental goals of cross-

Cultural identity is influenced by many factors, including ethnicity, nationality, race, religion, and language. As we grow up within a given culture, we learn our culture’s norms, or unwritten rules of behavior. And, we tend to act in accordance with those internalized norms without thinking. For example, according to the dominant cultural norms in the United States, babies usually sleep separately from their parents. But in many cultures around the world, it’s taken for granted that babies will sleep in the same bed as their parents (Mindell & others, 2010a, b). Members of these other cultures are often surprised and even shocked at the U.S. practice of separating babies from their parents at night. (In Chapter 9 on lifespan development, we discuss this topic at greater length.)

The tendency to use your own culture as the standard is called ethnocentrism. Ethnocentrism may be a natural tendency, but it can prevent us from understanding the behaviors of others (Bizumic & others, 2009). Ethnocentrism may also prevent us from being aware of how our behavior has been shaped by our own culture.

Extreme ethnocentrism can lead to intolerance toward other cultures. If we believe that our way of seeing things or behaving is the only proper one, other ways of behaving and thinking may seem laughable, inferior, wrong, or even immoral.

In addition to influencing how we behave, culture affects how we define our sense of self (Markus & Kitayama, 1991, 1998, 2010). For the most part, the dominant cultures of the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Europe can be described as individualistic cultures. Individualistic cultures emphasize the needs and goals of the individual over the needs and goals of the group (Henrich, 2014; Markus & Kitayama, 2010). In individualistic societies, the self is seen as independent, autonomous, and distinctive. Personal identity is defined by individual achievements, abilities, and accomplishments.

In contrast, collectivistic cultures emphasize the needs and goals of the group over those of the individual. Social behavior is more heavily influenced by cultural norms and social context than by individual preferences and attitudes (Owe & others, 2013; Talhelm & others, 2014). In a collectivistic culture, the self is seen as being much more interdependent with others. Relationships with others and identification with a larger group, such as the family or tribe, are key components of personal identity. The cultures of Asia, Africa, Mexico, and Central and South America tend to be collectivistic. About two-

The distinction between individualistic and collectivistic societies is useful in cross-

The Culture and Human Behavior boxes that we have included in this book will help you learn about human behavior in other cultures. They will also help you understand how culture affects your behavior, beliefs, attitudes, and values as well.

13

For example, one well-

Today, psychologists are keenly attuned to the influence of cultural factors on behavior (Heine, 2010; Henrich & others, 2010). Although many psychological processes are shared by all humans, it’s important to keep in mind that there are cultural variations in behavior. Thus, we have included Culture and Human Behavior boxes throughout this textbook to help sensitize you to the influence of culture on behavior—

THE EVOLUTIONARY PERSPECTIVE

Evolutionary psychology refers to the application of the principles of evolution to explain psychological processes and phenomena (Buss, 2009, 2011b). The evolutionary perspective reflects a renewed interest in the work of English naturalist Charles Darwin. As noted previously, Darwin’s (1859) first book on evolution, On the Origin of Species, played an influential role in the thinking of many early psychologists.

The theory of evolution proposes that the individual members of a species compete for survival. Because of inherited differences, some members of a species are better adapted to their environment than are others. Organisms that inherit characteristics that increase their chances of survival in their particular habitat are more likely to survive, reproduce, and pass on their characteristics to their offspring. But individuals that inherit less useful characteristics are less likely to survive, reproduce, and pass on their characteristics. This process reflects the principle of natural selection: The most adaptive characteristics are “selected” and perpetuated in the next generation.

Psychologists who take the evolutionary perspective assume that psychological processes are also subject to the principle of natural selection. As David Buss (2008) writes, “An evolved psychological mechanism exists in the form that it does because it solved a specific problem of survival or reproduction recurrently over evolutionary history.” That is, psychological processes that helped individuals adapt to their environments also helped them survive, reproduce, and pass those abilities on to their offspring (Confer & others, 2010). However, as you’ll see in later chapters, some of those processes may not necessarily be adaptive in our modern world (Loewenstein, 2010; Tooby & Cosmides, 2008).

14

Specialty Areas in Psychology

Many people think that psychologists primarily diagnose and treat people with psychological problems or disorders. In fact, psychologists who specialize in clinical psychology are trained in the diagnosis, treatment, causes, and prevention of psychological disorders, leading to a doctorate in clinical psychology.

In contrast, psychiatry is a medical specialty. A psychiatrist has earned a medical degree, either an M.D. or D.O., followed by several years of specialized training in the treatment of mental disorders. As physicians, psychiatrists can hospitalize people, order biomedical therapies such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), and prescribe medications. Clinical psychologists are not medical doctors and cannot order medical treatments. However, a few states have passed legislation allowing clinical psychologists to prescribe medications after specialized training (Riding-

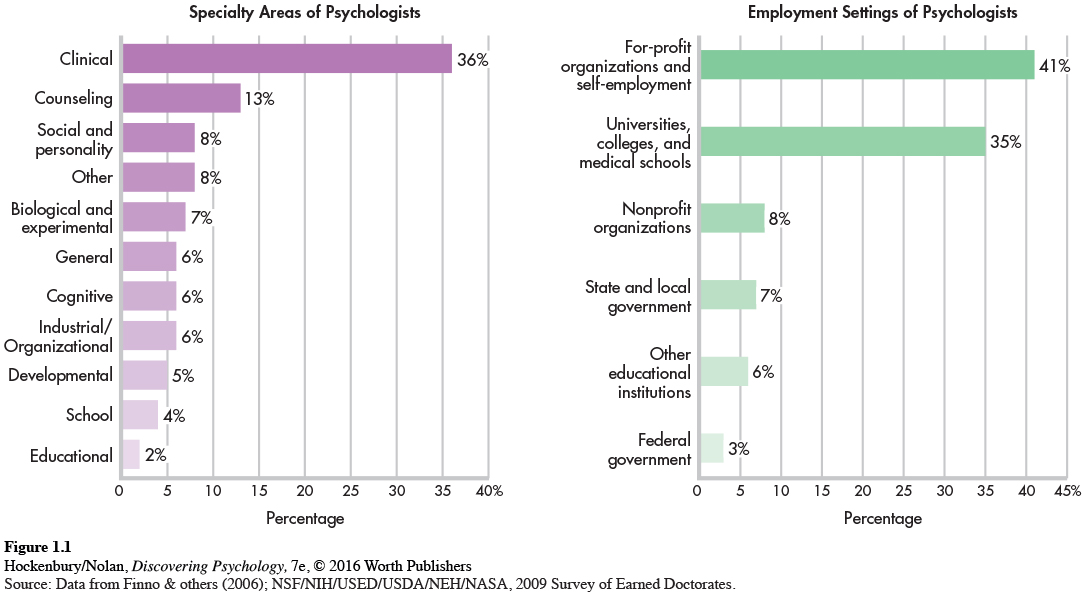

As you’ll learn, contemporary psychology is a very diverse discipline that ranges far beyond the treatment of psychological problems. This diversity is reflected in Figure 1.1, which shows the range of specialty areas and employment settings for psychologists. Table 1.1 provides a brief overview of psychology’s most important specialty areas.

15

Test your understanding of Contemporary Psychology with  .

.