Forgetting

WHEN RETRIEVAL FAILS

KEY THEME

Forgetting is the inability to retrieve information that was once available.

KEY QUESTIONS

What discoveries were made by Hermann Ebbinghaus?

How do encoding failure, interference, and decay contribute to forgetting, and how can prospective memory be improved?

What is repression and why is the topic controversial?

Forgetting is so common that life is filled with reminders to safeguard against forgetting important information. Cars are equipped with beeping tones so you don’t forget to fasten your seatbelt or turn off your headlights. Dentists thoughtfully send brightly colored postcards and call you the day before your scheduled appointment so that it doesn’t slip your mind.

243

Although forgetting can be annoying, it does have adaptive value. Our minds would be cluttered with mountains of useless information if we remembered the name of every person we’d ever met, or every word of every conversation we’d ever had (Kuhl & others, 2007; Roediger & others, 2010).

Psychologists define forgetting as the inability to remember information that was previously available. Note that this definition does not refer to the “loss” or “absence” of once-

Hermann Ebbinghaus

THE FORGETTING CURVE

German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus began the scientific study of forgetting in the 1870s. Because there was a seven-

Ebbinghaus’s goal was to determine how much information was forgotten after different lengths of time. But he wanted to make sure that he was studying the memory and forgetting of completely new material, rather than information that had preexisting associations in his memory. To solve this problem, Ebbinghaus (1885) created new material to memorize: thousands of nonsense syllables. A nonsense syllable is a three-

Ebbinghaus carefully noted how many times he had to repeat a list of 13 nonsense syllables before he could recall the list perfectly. To give you a feeling for this task, here’s a typical list:

DIS, ROH, LEZ, SUW, QOV, XAR, KUF, WEP, BIW, CUL, TIX, QAP, WEJ, ZOD

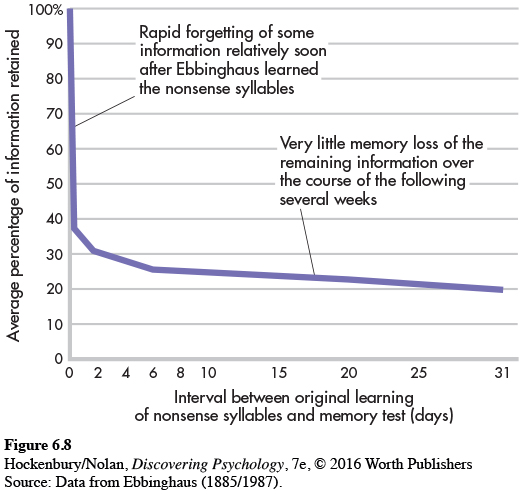

Once he had learned the nonsense syllables, Ebbinghaus tested his recall of them after varying amounts of time, ranging from 20 minutes to 31 days. He plotted his results in the now-

The Ebbinghaus forgetting curve reveals two distinct patterns in the relationship between forgetting and the passage of time. First, much of what we forget is lost relatively soon after we originally learned it. How quickly we forget material depends on several factors, such as how well the material was encoded in the first place, how meaningful the material was, and how often it was rehearsed.

244

In general, if you learn something in a matter of minutes on just one occasion, most forgetting will occur very soon after the original learning—

Second, the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve shows that the amount of forgetting eventually levels off. In fact, there’s very little difference between how much Ebbinghaus forgot eight hours later and a month later. The information that is not quickly forgotten seems to be remarkably stable in memory over long periods of time.

Ebbinghaus’s work with nonsense syllables and his forgetting curve have achieved legendary status in psychology. However, it turns out that the pattern of forgetting that Ebbinghaus identified is not universal. Under some conditions, memory for new information actually improves over time (Erdelyi, 2010; Roediger, 2008).

One well-

Why Do We Forget?

Ebbinghaus was a pioneer in the study of memory. His major contribution was to identify a basic pattern of forgetting: rapid forgetting of some information relatively soon after the original learning, followed by stability of the memories that remain. But what causes forgetting? Psychologists have identified several factors that contribute to forgetting, including encoding failure, decay, interference, and motivated forgetting.

ENCODING FAILURE

IT NEVER GOT TO LONG-

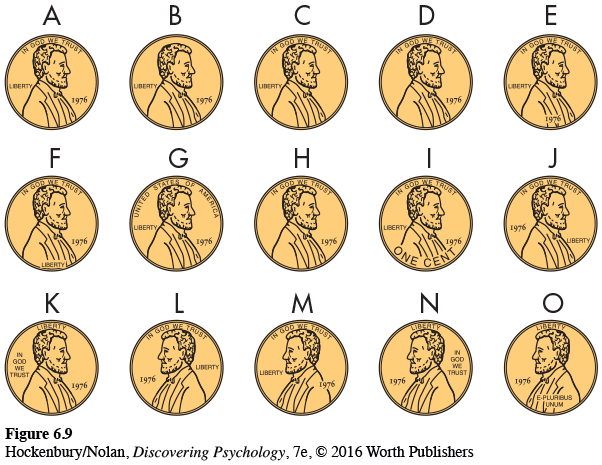

Without rummaging through your loose change, take a look at Figure 6.9. Circle the drawing that accurately depicts the face of a U.S. penny. Now, check your answer against a real penny. Were you correct?

When this task was presented to participants in one study, fewer than half of them picked the correct drawing (Nickerson & Adams, 1982). The explanation? Unless you’re a coin collector, you’ve probably never looked carefully at a penny. Even though you may have handled thousands of pennies, chances are that you’ve encoded only the most superficial characteristics of a penny—

In a follow-

245

As these simple demonstrations illustrate, one of the most common reasons for forgetting is called encoding failure—we never encoded the information into long-

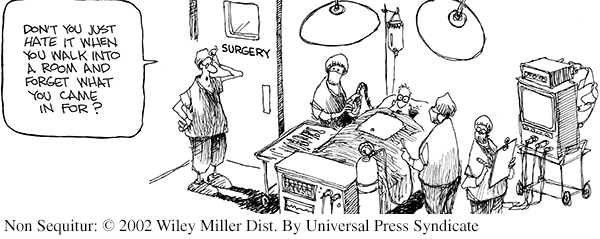

Encoding failure can also help explain everyday memory failures due to absentmindedness. Absentmindedness occurs because you don’t pay enough attention to a bit of information at the time when you should be encoding it, such as in which aisle you parked your car at the airport. Absentminded memory failures often occur because your attention is divided. Rather than focusing your full attention on what you’re doing, you’re also thinking about other matters (McVay & Kane, 2010).

Research has shown that divided attention at the time of encoding tends to result in poor memory for the information (Craik & others, 1996; Riby & others, 2008; Smallwood & others, 2007). Such absentminded memory lapses are especially common when you’re performing habitual actions that don’t require much thought, such as parking your car in a familiar parking lot or setting down your cell phone, keys, and wallet or purse when you come home. In some situations, divided attention might even contribute to déjà vu experiences, as we discuss in the In Focus box on the next page.

Absentmindedness is also implicated in another annoying memory problem—

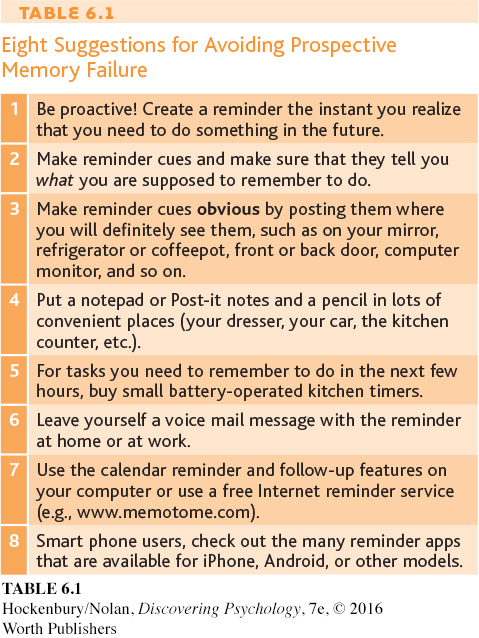

Rather than encoding failure, prospective memory failures are due to retrieval cue failure—the inability to recall a memory because of missing or inadequate retrieval cues. For example, you forget to submit your credit card payment on time and incur a late fee. The problem with this sort of scenario is that there is no strong, distinctive retrieval cue embedded in the situation. This is why ovens are equipped with timers that buzz and why reminder programs are popular smart phone apps. Such strategies provide distinctive retrieval cues that will hopefully trigger those prospective memories at the appropriate moment. Table 6.1 lists additional suggestions to help minimize prospective memory failures.

DECAY THEORY

FADING WITH THE PASSAGE OF TIME

According to decay theory, we forget memories because we don’t use them and they fade away over time as a matter of normal brain processes. The idea is that when a new memory is formed, it creates a memory trace—a distinct structural or chemical change in the brain. Over time, the normal metabolic processes of the brain are thought to erode the memory trace, especially if it is not “refreshed” by frequent rehearsal. The gradual fading of memories, then, would be similar to the fading of letters on billboards or newsprint exposed to environmental elements, such as sunlight.

Although decay theory makes sense intuitively, too much evidence contradicts it (Jonides & others, 2008). Look again at the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve on page 244. If memories simply faded over time, you would expect to see a steady decline in the amount of information remembered with the passage of time. Instead, once the information held in memory stabilizes, it changes very little over time. In other words, the rate of forgetting actually decreases over time (Wixted, 2004).

IN FOCUS

Déjà Vu Experiences: An Illusion of Memory?

246

The term déjà vu is French for “already seen.” A déjà vu experience involves brief but intense feelings of familiarity in a new situation (Gerrans, 2012). Psychology’s interest in déjà vu extends back to the late 1800s, when the famous American psychologist William James (1890, 1902) wrote about these experiences.

Déjà Vu Characteristics

Déjà vu experiences are common. Psychologist Alan Brown (2004) analyzed the results of more than 30 surveys and found that about two-

Although typically triggered by a visual scene, déjà vu experiences can involve any of the senses. For example, blind people can also experience déjà vu (O’Connor & Moulin, 2006). Interestingly, there is a higher incidence of déjà vu experiences in people who are well educated, travel frequently, often watch movies, and regularly remember their dreams (Brown, 2003; Cleary, 2008). We’ll come back to that last point shortly.

Because déjà vu experiences can be so compelling, people sometimes assume that the experience must have been an instance of clairvoyance, telepathy, a memory of a past life experience, or some other paranormal experience. But rather than paranormal explanations, contemporary psychologists believe that déjà vu can provide insights into basic memory processes (Brown & Marsh, 2010).

Explaining Déjà Vu

Let’s suppose that you have an intense déjà vu experience as you enter Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium. You know you’ve never visited the Shedd Aquarium before, so there is no memory source you can identify for the intense feeling of recognition.

Psychologist Anne Cleary (2008) believes this sense of familiarity suddenly arises when features in the current situation trigger the sensation of matching features already contained in an old memory. You recognize some details of the memory as familiar, but can’t pinpoint a source for that familiarity (Cleary & others, 2012). This is what memory researchers refer to as a disruption in source memory or source monitoring–your ability to remember the original details or features of a memory, including when, where, and how you acquired the information or had the experience. Interestingly, people who are more sensitive to similarities in their surroundings are also more likely to have déjà vu experiences (Sugimori & Kusumi, 2014).

Most likely, your déjà vu experience was due to source amnesia: You have indirectly experienced this scene or situation before, but you’ve forgotten the memory’s source. Earlier we noted that people who are well educated, travel a lot, often watch movies, and remember their dreams are more prone to déjà vu experiences (Cleary, 2008). Each of these is a potential gold mine of memory retrieval clue fragments that can match elements of the current scene, triggering a sense of familiarity. Of course, had you immediately recalled the previous source from a little over two years ago–

Another memory explanation for déjà vu involves a form of encoding failure called inattentional blindness, which we discussed in Chapter 4. According to the inattentional blindness explanation, déjà vu can be produced when you’re not really paying attention to your surroundings (Brown, 2005; Brown & Marsh, 2010). So, suppose you’re oblivious to your surroundings while chatting on your cell phone as you walk toward the Shedd Aquarium. As the call ends, you glance up at the entrance to the Shedd Aquarium and bang! A déjà vu experience! In this case, the feeling that you have been there before is due to the fact that you really have been there before–

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that déjà vu experiences are a type of ESP, and may be examples of precognition or memories from a previous lifetime?

A different explanation comes from the brain itself. Neurological evidence suggests that at least some instances of déjà vu are related to brain dysfunction (Bartolomei & others, 2012). In particular, it has long been known that déjà vu experiences can be triggered by temporal lobe disruptions (see Brázdil & others, 2012). For many people with epilepsy, the seizures often originate in the temporal lobe. In these people, a déjà vu experience sometimes occurs just prior to a seizure (Lytton, 2008). For most people, however, déjà vu experiences probably involve the common memory processes of source amnesia and inattentional blindness.

247

Beyond that point, many studies have shown that information can be remembered decades after it was originally learned, even though it has not been rehearsed or recalled since the original memory was formed (Custers & Ten Cate, 2011). As we discussed earlier, the ability to access memories is strongly influenced by the kinds of retrieval cues provided when memory is tested. If the memory trace simply decayed over time, the presentation of potent retrieval cues should have no effect on the retrieval of information or events experienced long ago—

So have contemporary memory researchers abandoned decay theory as an explanation of forgetting? Not completely. Although decay is not regarded as the primary cause of forgetting, many of today’s memory researchers believe that it contributes to forgetting (Altmann, 2009; Portrat & others, 2008).

INTERFERENCE THEORY

MEMORIES INTERFERING WITH MEMORIES

According to the interference theory of forgetting, forgetting is caused by one memory competing with or replacing another memory. The most critical factor is the similarity of the information. The more similar the information is in two memories, the more likely it is that interference will be produced.

There are two basic types of interference. Retroactive interference is backward-

Proactive interference is forward-

MOTIVATED FORGETTING

FORGETTING UNPLEASANT MEMORIES

Motivated forgetting refers to the idea that we forget because we are motivated to forget, usually because a memory is unpleasant or disturbing. One form of motivated forgetting, called suppression, involves the deliberate, conscious effort to forget information. For example, after seeing a disturbing report of a horrendous crime or massacre on the evening news, you consciously avoid thinking about it, turning your attention to other matters. According to some researchers, over time and with repeated effort, pushing an unwanted memory out of awareness may make the memory less accessible (M. C. Anderson & Levy, 2009; Meier & others, 2011).

Another form of motivated forgetting is fundamentally different and much more controversial. Repression can be defined as motivated forgetting that occurs unconsciously (Langnickel & Markowitsch, 2006). With repression, all memory of a distressing event or experience is blocked from conscious awareness.

248

As we’ll discuss in greater detail in Chapters 10 (Personality) and 14 (Therapies), the idea of repression is a cornerstone of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud’s famous theory of personality and psychotherapy (Knafo, 2009). Freud (1904) believed that psychologically threatening emotions, feelings, conflicts, and urges, especially those that originated in early childhood, become repressed. Even though they are blocked and unavailable to consciousness, the repressed conflicts continue to unconsciously influence the person’s behavior, thoughts, and personality, often in maladaptive or unhealthy ways.

Among clinical psychologists who work with psychologically troubled people, the notion that behavior can be influenced by repressed memories is accepted, but not as widely as it once was (Gleaves & others, 2004; Patihis & others, 2014). Among the general public, many people believe that we are capable of repressing memories of unpleasant events. However, trying to scientifically confirm and study the influence of memories that a person does not remember is tricky, if not impossible.

One obvious problem is determining whether a memory has been “repressed” or simply forgotten. For example, several studies have found that people are better able to remember positive life experiences than negative life experiences (Lambert & others, 2010). Is that because unhappy experiences have been “repressed”? Or is it simply that people are less likely to think about, talk about, dwell on, or rehearse unhappy memories?

Among psychologists, repression is an extremely controversial topic (see Erdelyi, 2006a, 2006b). At one extreme are those who believe that true repression never occurs (Hayne & others, 2006). At the other extreme are those who are convinced that repressed memories are at the root of many psychological problems, particularly repressed memories of childhood sexual abuse (Gleaves & others, 2004). This latter contention gave rise to a form of psychotherapy involving the recovery of repressed memories. Later in the chapter, we’ll explore this controversy in the Critical Thinking box “The Memory Wars: Recovered or False Memories?”