Closing Thoughts

Over the course of this chapter, you’ve encountered firsthand some of the most influential contributors to modern psychological thought. As you’ll see in Chapter 14, the major personality perspectives provide the basis for many forms of psychotherapy. Clearly, the psychoanalytic, humanistic, social cognitive, and trait perspectives each provide a fundamentally different way of conceptualizing personality. That each perspective has strengths and limitations underscores the point that no single perspective can explain all aspects of human personality. Indeed, no one personality theory could explain why Kenneth and Julian were so different. And, given the complex factors involved in human personality, it’s doubtful that any single theory ever will capture the essence of human personality in its entirety. Even so, each perspective has made important and lasting contributions to the understanding of human personality.

PSYCH FOR YOUR LIFE

Possible Selves: Imagine the Possibilities

Some psychologists believe that a person’s self-

According to psychologist Hazel Markus and her colleagues, an important aspect of your self-

The Influence of Hoped-

Possible selves are more than just idle daydreams or wishful fantasies. In fact, possible selves influence our behavior in important ways (Markus & Nurius, 1986; Oyserman & James, 2011). We’re often not aware of the possible selves that we have incorporated into our self-

448

Imagine that you harbor a hoped-

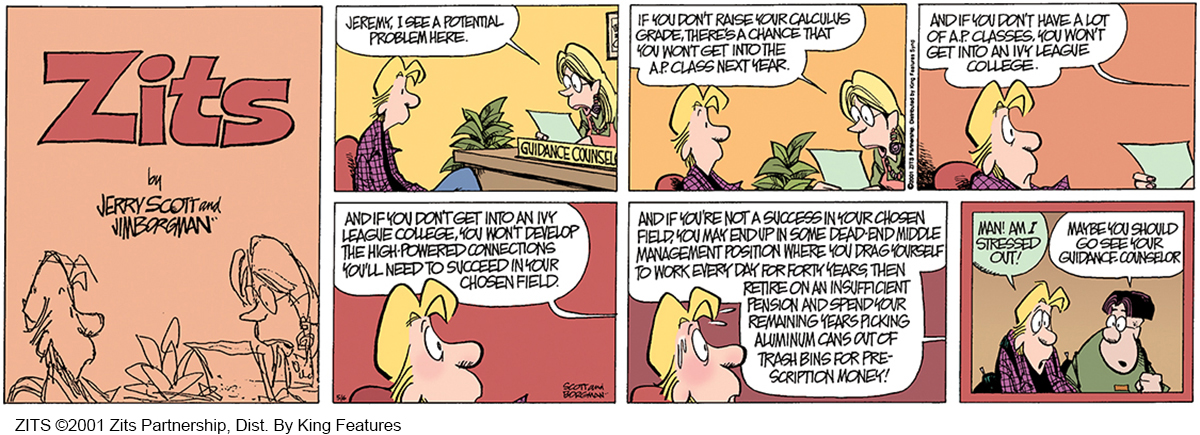

Dreaded possible selves can also influence behavior, whether they are realistic or not. Consider your author Don’s father, Kenneth. Although never wealthy, Kenneth was financially secure throughout his long life. Yet Kenneth had lived through the Great Depression and witnessed firsthand the financial devastation that occurred in the lives of countless people. Kenneth seems to have harbored a dreaded possible self of becoming penniless. When Kenneth died, the family found a $100 bill tucked safely under his mattress.

A positive possible self, even if it is not very realistic, can protect an individual’s self-

Possible Selves, Self-

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that if you can imagine yourself taking the steps to become successful, you’re more likely to actually become successful?

Self-

Thus, people who vividly imagine possible selves as “successful because of hard work” persist longer and expend more effort on tasks than do people who imagine themselves as “unsuccessful despite hard work” (Ruvolo & Markus, 1992). The motivation to achieve academically increases when your possible selves include a future self who is successful because of academic achievement (Oyserman & James, 2011; Oyserman & others, 2015). To be most effective, possible selves should incorporate concrete strategies for attaining goals. For example, students who visualized themselves taking specific steps to improve their grades—

Applying the Research: Assessing Your Possible Selves

How can you apply these research findings to your life? First, it’s important to stress again that we’re often unaware of how the possible selves we’ve mentally constructed influence our beliefs, actions, and self-

Take a few moments and jot down the “possible selves” that are active in your working self-

Next year, I expect to be . . .

Next year, I am afraid that I will be . . .

Next year, I want to avoid becoming . . .

After focusing on the short-

How are your possible selves affecting your current motivation, goals, feelings, and decisions?

Are your possible selves even remotely plausible?

Are they pessimistic and limiting?

Are they unrealistically optimistic?

449

Finally, ask yourself honestly: What realistic strategies are you using to try to become the self that you want to become? To avoid becoming the selves that you dread?

How can you improve the likelihood that you will achieve some of your possible selves? One approach is to link your expectations and hopes to concrete strategies about how to behave to reach your desired possible self (Oyserman & others, 2004).

These questions should help you gain some insight into whether your possible selves are influencing your behavior in productive, constructive ways. If they are not, now is an excellent time to think about replacing or modifying the possible selves that operate most powerfully in your own self-