Personality Disorders

562

MALADAPTIVE TRAITS

KEY THEME

The personality disorders are characterized by inflexible, maladaptive patterns of thoughts, emotions, behavior, and interpersonal functioning.

KEY QUESTIONS

How do people with a personality disorder differ from people who are psychologically well adjusted?

What behaviors and personality characteristics are associated with antisocial and borderline personality disorders?

Like every other person, you have your own unique personality—the consistent and enduring patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving that characterize you as an individual. As we described in Chapter 10, your personality can be described as a specific collection of personality traits. Your personality traits are relatively stable predispositions to behave or react in certain ways. In other words, your personality traits reflect different dimensions of your personality.

By definition, personality traits are consistent over time and across situations. But that’s not to say that personality traits are etched in stone. Rather, the psychologically well-

In contrast, someone with a personality disorder has personality traits that are inflexible and maladaptive across a broad range of situations. However, the behavior of people with personality disorders goes well beyond that of a normal individual who occasionally experiences an emotional meltdown or who is grumpier, more aloof, or more self-

The personality disorders involve pervasive patterns of perceiving, relating to and thinking about the self, other people, and the environment that interfere with long-

Many researchers believe that personality disorders reflect conditions in which “normal” personality traits are taken to an abnormal extreme (Samuel & others, 2010; Trull & Widiger, 2008). For example, it’s normal to feel uneasy or sad when separated from a loved one. In a personality disorder, however, these responses reach pathological extremes. Rather than uneasiness, a person might experience intense feelings of desperation and intense anxiety. And rather than sadness, the person might experience unbearably intense feelings of abandonment and emptiness.

Despite the fact that the maladaptive personality traits consistently cause personal or social turmoil, people with personality disorders often blame others for their difficulties. Even if they are aware of their maladaptive personality patterns, they typically don’t think there’s anything wrong with them. In other words, they are unable to see that their inflexible style of thinking and behaving is at the root of their personal and social difficulties. Consequently, people with personality disorders often don’t seek help.

563

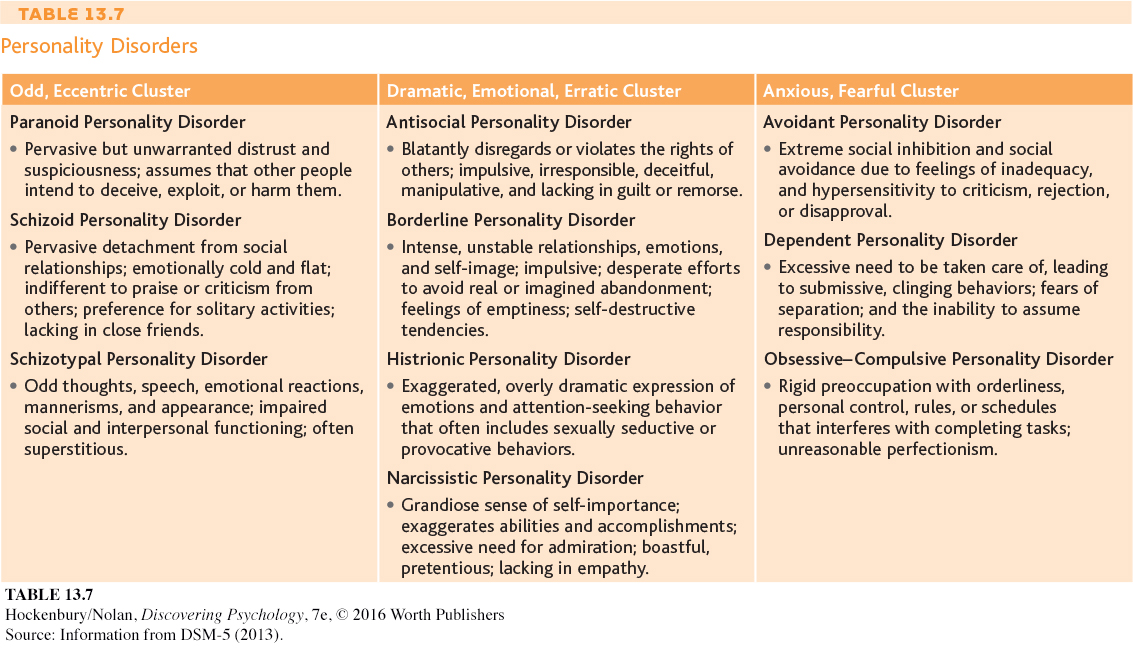

DSM-

For the first time, DSM-

In this section, we’ll focus our discussion on two of the more serious personality disorders, antisocial personality disorder and borderline personality disorder. These two disorders are also among the most thoroughly researched. Because clinicians use the older method of diagnosis more commonly than the newer one, we will refer to it throughout our discussion.

Antisocial Personality Disorder

VIOLATING THE RIGHTS OF OTHERS—

Often referred to as a psychopath or sociopath, the individual with antisocial personality disorder has the ability to lie, cheat, steal, and otherwise manipulate and harm other people. And when caught, the person shows little or no remorse for having caused pain, damage, or loss to others (Patrick, 2007). It’s as though the person has no conscience or sense of guilt. This pattern of blatantly disregarding and violating the rights of others is the central feature of antisocial personality disorder (DSM-

564

More recently, researchers have argued that the definitions of psychopath and sociopath are different from the criteria for antisocial personality disorder, despite the fact that all three are often used interchangeably. For example, Arielle Baskin-

Evidence of the maladaptive personality patterns associated with antisocial personality disorder is often seen in childhood or early adolescence (Diamantopoulou & others, 2010; Hiatt & Dishion, 2008). In many cases, the child has repeated run-

Deceiving and manipulating others for their own personal gain is another hallmark of individuals with antisocial personality disorder. With an uncanny ability to look you directly in the eye and speak with complete confidence and sincerity, they will lie in order to gain money, sex, or whatever their goal may be. Often, they are contemptuous about the feelings or rights of others, blaming the victim for his or her stupidity. This quality makes antisocial personality disorder especially difficult to treat because clients often manipulate and lie to their therapists, too (McMurran & Howard, 2009).

Because they are consistently irresponsible, individuals with antisocial personality disorder often fail to hold a job or meet financial obligations. Their past is often checkered with arrests and jail sentences. High rates of alcoholism and other forms of substance abuse are also strongly associated with antisocial personality disorder (Hasin & others, 2011; Fridell & others, 2008). However, by middle to late adulthood, the antisocial tendencies of such individuals tend to diminish.

Borderline Personality Disorder

565

CHAOS AND EMPTINESS

Borderline individuals are the psychological equivalent of third-

This is how psychologist Marsha Linehan (2009) describes the chaotic, unstable world of people with borderline personality disorder (BPD). Borderline personality disorder is characterized by impulsiveness and chronically unstable emotions, relationships, and self-

Relationships with others are as chaotic and unstable as the person’s moods. The person with borderline personality disorder has a chronic, pervasive sense of emptiness. Desperately afraid of abandonment, she alternately clings to others and pushes them away. Because her sense of identity is so fragile, she constantly seeks reassurance and self-

Relationships careen out of control as the person shifts from inappropriately idealizing the newfound lover or friend to viewing them with complete contempt or hostility. She sees herself, and everyone else, as absolutes: ecstatic or miserable, perfect or worthless (Arntz & ten Haaf, 2012; de Montigny-

Often, the deep despair and inner emptiness that people with BPD experience are outwardly expressed in self-

Borderline personality disorder is often considered to be the most serious and disabling of the personality disorders. People with this disorder often also suffer from depression, substance abuse, and eating disorders (Mercer & others, 2009; Walter & others, 2009). And because they often lack control over their impulses, self-

Along with being among the most severe of the personality disorders, borderline personality disorder is also the most commonly diagnosed. A recent survey found that BPD was more prevalent than previously thought. Estimates suggest that BPD affects about 6 percent of the population, or possibly some 18 million Americans (Grant & others, 2008). The researchers also found the highest prevalence of borderline personality disorder among women, people in lower-

WHAT CAUSES BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER?

As with the other personality disorders, multiple factors have been implicated. Because people with borderline personality disorder have such intense and chronic fears of abandonment and are terrified of being alone, some researchers believe that a disruption in attachment relationships in early childhood is an important contributing cause (Barone & others, 2011). Dysfunctional family relationships are common: Many borderline patients report having experienced neglect or physical, sexual, or emotional abuse in childhood (Ball & Links, 2009; Watson & others, 2006).

A more comprehensive theory, called the biosocial developmental theory of borderline personality disorder, has been proposed by Marsha Linehan (1993; Crowell & others, 2009). According to this view, borderline personality disorder is the outcome of a unique combination of biological, psychological, and environmental factors. Some children are born with a biological temperament that is characterized by extreme emotional sensitivity, a tendency to be impulsive, and the tendency to experience negative emotions. Linehan believes that borderline personality disorder results when such a biologically vulnerable child is raised by caregivers who do not teach him how to control his impulses or help him learn how to understand, regulate, and appropriately express his emotions (Crowell & others, 2009).

566

In some cases, Linehan believes, parents or caregivers actually shape and reinforce the child’s pattern of frequent, intense emotional displays by their own behavior. For example, they may sometimes ignore a child’s emotional outbursts and sometimes reinforce them. In Linehan’s theory, a history of abuse and neglect may be present but is not a necessary ingredient in the toxic mix that produces borderline personality disorder. Despite the difficulties faced by people suffering from borderline personality disorder, treatments developed by Linehan and her colleagues have been shown to help patients to manage this mental illness (see Bohus & others, 2000).