CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

As powerfully transformative as the processes of globalization are, they are unlikely to result in cultural homogenization any time soon. As we learned by examining globalization’s interaction with each of cultural geography’s five themes, we do not yet live in a placeless world. In fact, we have observed many trends suggesting that globalization will produce more geographic diversity and many unintended and unforeseen outcomes in our future.

In closing, it is our hope that we have excited your interest in the world’s cultural diversity. To paraphrase the words of Aldous Huxley, we hope that our vicarious world travels have left you “poorer by exploded convictions” and “perished certainties,” but richer by what you have seen. Perhaps we, like Huxley, set out on this journey with preconceptions of how people should best “live, be governed, and believe.” When one travels—even if just through the pages of a geography book as we have—such convictions often get mislaid. The main message of Contemporary Human Geography is that we will best be prepared to thrive in this new millennium if we maintain a willingness to question even our most closely held convictions and remain open to the boundless capacity of human cultural expression to surprise and amaze.

486

SEEING GEOGRAPHY

SEEING GEOGRAPHY

Global Reach

What do these images convey about empire and globalization, and their similarities and differences?

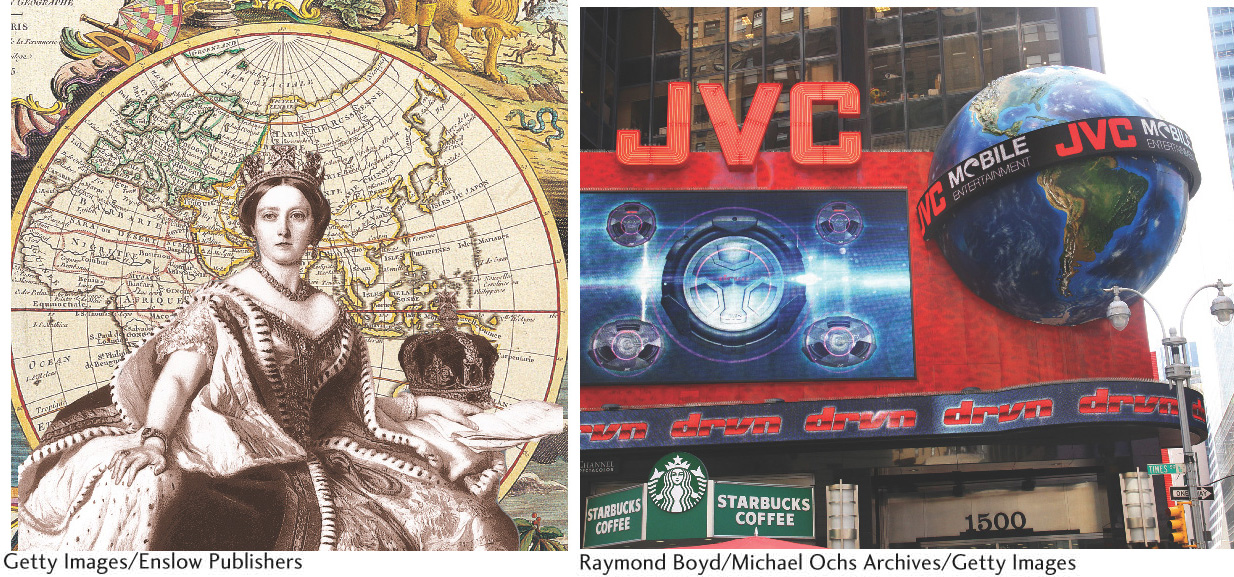

Two images of global reach, more than a century apart (Queen Victoria with world map; a JVC advertisement).

(Left: Getty Images/Enslow Publishers; Right: Raymond Boyd/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images.)

In his book Apollo’s Eye, the late cultural geographer Denis Cosgrove attempted to interpret the power represented in images of the globe and to show how the practices of globalization are historically rooted in a Western cultural history of imagining, seeing, and representing the globe. We will try a little of this interpretive method on these two images.

The image on the left shows Queen Victoria circa 1850 in front of a world map oriented so that the majority of Britain’s territorial empire is displayed. We know that during this period of European history, the queen was sovereign, meaning that she personified, even embodied, Britain and its colonial empire. The image is scaled such that the queen’s arm span matches the span of the British Empire. She is positioned in front of the map, emphasizing her authority and power over it. With power and authority comes responsibility; the viewer is meant to read in the queen’s pose and dress a moral role as protector and civilizing force. Foregrounded as she is, then, all lines of power, authority, and moral right and responsibility in empire run through her.

The image on the right is an advertisement for JVC, a transnational consumer electronics company that began as the Victor Talking Machine Company of Japan, Limited, in 1927. In the advertisement, photographed in 2004, the company’s logo, “JVC,” is scaled to continental size. The message conveyed is one of global dominance and global reach. It also conveys the message of one company bringing together the world, a goal that JVC’s web site describes as “contributing to the global community through cultural activities” with corporate underwriting. Finally, the advertisement is meant to express through the image of the globe the fact that JVC now has a network of manufacturing sites throughout Asia, the Americas, and Europe as well as sales subsidiaries in many more regions.

487

What do these images tell us about continuity and change from empire to globalization? We see a common theme in the claim of global reach. In the JVC ad, it is expressed as the company’s ability to span the globe with its products and services. In the image with Queen Victoria, it is expressed in the cartographic representation of Britain’s global empire. We can also identify significant differences between the emotional and affective meaning of British Empire and globalization conveyed by these images. Under empire, the queen personified British imperial rule, and allegiance to the queen was required of all imperial subjects. Under globalization, on the other hand, allegiance is constructed between the consumer and transnational corporations. Corporations are faceless rather than personified, represented by abstract logos rather than by living, breathing sovereigns. In summary, we can see in these images both the roots of globalization in empire as well as the significant differences between the two kinds of global power.

DOING GEOGRAPHY

DOING GEOGRAPHY

Interpreting the Imagery of Globalization

The mandate of large corporations today, nearly regardless of the type of service or good they produce, is to go global or go bankrupt. In addition to staying competitive, going global gives a company a certain cachet and consumer appeal, the way that being “modern” did in previous decades. Transnational corporations also stress other popular notions related to globalization, such as respect for the world’s cultural diversity and concern for the global environment.

For this activity, you will use your interpretive skills to look at the way the processes of globalization are represented in corporate-produced visual imagery and text. Using the steps below, try to find representations of globalization in more than one medium, including product packaging, magazine advertisements, and corporate web sites.

Steps to Interpreting the Imagery of Globalization

Step 1:

Concentrate on one type of industry, such as pharmaceuticals or automobiles, or several.

Step 2:

Look for materials that include visual and textual representations of the globe, the Earth, or the world, and remember to make use of the five themes of cultural geography.

Step 3:

Analyze and interpret each of the samples that you select by setting up a series of questions such as: What popular notions about globalization are emphasized? How much validity do these representations carry? This is not the same as asking about the truthfulness or falseness of an ad. Rather it is to ask, for example: What does going to the Hard Rock Café and buying a T-shirt have to do with “saving the planet”?

In the cases of visual imagery, look carefully at the way objects are arranged and scaled in relation to one another.

How is power represented in the imagery?

Does power lie with the individual consumer or the corporation?

How are local-global linkages represented?

Are the activities of global corporations given a moral authority and, if so, how?

Step 4:

Provide a written summary of your findings and analysis. Include a copy of the image or images that you use and make sure to reference your sources.

As you do this exercise, bear in mind the power of transnational corporations in an era of globalization. Think about the importance of understanding how the images and texts they produce give meaning to our world, our places, and our landscapes.

488

Chapter 11 LEARNING OBJECTIVES REEXAMINED

Chapter 11

LEARNING OBJECTIVES REEXAMINED

11.1

Describe the possible futures of place and region, and explain their driving forces.

How has the Internet affected regional boundaries?

11.2

Explain how current trends will shape future mobilities.

What role has the automobile played in transforming China’s urban culture?

11.3

Analyze the relationship of contemporary globalization to historical processes and its likely effects on the future.

What are the arguments from the left and right of the political spectrum in terms of globalization’s effect on the future?

11.4

Relate how the continuation of current globalizing trends will shape future nature-culture relations.

What impact do recent globalization trends have on current and future sustainability?

11.5

Identify likely future landscapes.

How is globalization represented in urban landscapes?

KEY TERMS

Match each of the terms on the left with its definition on the right. Click on the term first and then click on the matching definition. As you match them correctly they will move to the bottom of the activity.

Question

Xuo/bHleCMalwkc9r+SXg128cOqKLFEQ6wvTH4B+AG8kHRM7ENCz+ZQX1Wmbc+Y3zxBUixhMcoiJJId/Hpqnn7fCLlenR6E1u+ItoNxDHANa17OhTNrnlJYd2zPZTG8HuqdW/i92kNfAh5Ubo/9LiMjMYRBlHlnpbKtWZ7VD4r+cpaQPTvR1+tU/NabkhrnxXjsOLys/0Q21hbHgWSo4MmpjbHEgTD5jgmMpox9v4H4w10yx8KBsZMOd98whKu4Ik5ojF89FDLJ8a6H9mvnVV9+xsRI=The Geography of the Future on the Internet

You can learn more about the geography of the future on the Internet at the following web sites:

An Atlas of Cyberspaces

http://www.cybergeography.org/atlas/atlas.html

Here, cyberspaces are made visible by Martin Dodge: graphic representations of the geography of the electronic territories of the Internet, the World Wide Web, and other new cyberspaces help you to visualize and comprehend the digital “landscapes” beyond your computer screen.

The Hawaii Research Center for Futures Studies

http://www.futures.hawaii.edu/

One of the best-known institutions for future studies. The Hawaii State Legislature created it in 1971 to train students in future thinking for work in government and business.

Millennium Project: World Federation of UN Associations

http://www.millennium-project.org/

A global, participatory, futures-research think tank of futurists, scholars, business planners, and policy makers. It produces numerous future scenarios and such documents as the annual “State of the Future” report.

World Future Society

http://www.wfs.org/

A scientific and educational association exploring how social and technological developments are shaping the future. The society serves as a clearinghouse for forecasts, recommendations, and alternative scenarios. It publishes, among other periodicals, the bimonthly journal The Futurist.

World Futures Studies Federation

http://www.wfsf.org/

Founded in 1967 to further research and education in future studies. It is made up of hundreds of individuals and institutions worldwide that together create a global network of researchers, teachers, policy analysts, and activists.

Sources

Adams, William. 2001. Green Development: Environment and Sustainability in the Third World. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Airriess, Christopher A. 2001. “Regional Production, Information-Communication Technology, and the Developmental State: The Rise of Singapore as a Global Container Hub.” Geoforum 32: 235-254.

Barlow, John P. 1995. “Cyberhood Versus Neighborhood.” Special issue of Utne Reader 68(3): 52-64.

Beaverstock, Jonathan, Phillip Hubbard, and John Short. 2004. “Getting Away with It? Exposing the Geographies of the Super-Rich.” Geoforum 35(4): 401-407.

Bradsher, Keith. 2012. “China Blocks Web Access to Times After Article.” New York Times, 25 October, p. A12.

Bruntland, H. 1987. Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press (for the World Commission on Environment and Development).

Bunge, William. 1973. “The Geography of Human Survival.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 63: 275-295.

Cosgrove, Denis. 2001. Apollo’s Eye: A Cartographic Genealogy of the Earth in the Western Imagination. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Crouch, David (ed.). 1999. Leisure/Tourism Geographies: Practices and Geographical Knowledge. London: Routledge.

Crum, Shannon L. 2000. “The Spatial Diffusion of the Internet.” PhD dissertation, University of Texas at Austin.

Cutter, Susan, and William Soleki. 2013. “Urban Systems, Infrastructure, and Vulnerability I.” Federal Advisory Committee Draft Climate Assessment Report Released for Public Review. National Climate Assessment and Development Advisory Committee, U.S. Global Change Research Program. http://ncadac.globalchange.gov/.

489

Domosh, Mona. 2006. American Commodities in an Age of Empire. New York: Routledge.

Drummond, Ian, and Terry Marsden. 1999. The Condition of Stability: Global Environment Change. New York: Routledge.

Durand, Jorge, and Douglas S. Massey. 2010. “New World Orders: Continuities and Changes in Latin American Migration.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 630: 20-52.

Ehrenreich, Barbara. 2004. “Earth People vs. Wal-Martians.” New York Times, 25 July, p. 11.

Elwood, Wayne. 2001. The No-Nonsense Guide to Globalization. London: Verso.

Feld, Stephen. 2001. “A Sweet Lullaby for World Music.” In Arjun Appadurai (ed.), Globalization, pp. 189-216. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Ferguson, Andrew. 2004. “Wal-Mart Opponents Launch Two-Front Attack.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 20 June, p. C2.

Firebaugh, Glenn. 2003. The New Geography of Global Inequality. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Flack, Wes. 1997. “American Microbreweries and Neolocalism.” Journal of Cultural Geography 16(2): 37-53.

Friedman, Thomas. 2005. The World Is Flat: A Short History of the Twenty-First Century. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Fryer, Donald. 1974. “A Geographer’s Inhumanity to Man.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 64: 479-482.

Gilbert, Anne, and Paul Villeneuve. 1999. “Social Space, Regional Development, and the Infobahn.”Canadian Geographer 43: 114-117.

Hanson, Susan, Robert Nicholls, N. Ranger, S. Hallegatte, J. Corfee-Morlot, C. Herweijer, and J. Chateau. 2011. “A Global Ranking of Port Cities with High Exposure to Climate Extremes.” Climatic Change 104: 89-111.

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. 2000. Empire. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Hessler, Peter. 2007. “Wheels of Fortune: The People’s Republic Learns to Drive.” The New Yorker, 26 November, p. 104.

Hollander, Gail. 2004. “Agricultural Trade Liberalization, Multifunctionality, and Sugar in the South Florida Landscape.” Geoforum 35: 299-312.

Hooson, David (ed.). 1994. Geography and National Identity. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hudson, Ray. 2000. “One Europe or Many? Reflections on Becoming European.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 25: 409-426.

Huxley, Aldous. 1926. Jesting Pilate: An Intellectual Holiday. New York: George H. Doran.

Iyer, Pico. 2000. The Global Soul: Jet Lag, Shopping Malls, and the Search for Home. New York: Knopf.

Keating, Michael. 1998. The New Regionalism in Western Europe. Northampton, Mass.: Edward Elgar.

Keeling, David J. 1999. “Neoliberal Reform and Landscape Change in Buenos Aires.” Yearbook, Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers 25: 15-32.

Kelly, Philip F. 2000. Landscapes of Globalization. London: Routledge.

Kitchen, Rob, and Martin Dodge. 2002. “Emerging Geographies of Cyberspace.” In R. J. Johnston, Peter Taylor, and Michael Watts (eds.), Geographies of Global Change: Remapping the World, 2nd ed., pp. 340-354. Oxford: Blackwell.

Knox, Paul. 2002. “World Cities and the Organization of Global Space.” In R. J. Johnston, Peter Taylor, and Michael Watts (eds.), Geographies of Global Change: Remapping the World, 2nd ed., pp. 328-339. Oxford: Blackwell.

Kraus, Clifford. 2002. “Returning Tundra’s Rhythm to the Inuit, in Film.” The New York Times, 30 March, p. A4.

Kunstler, James H. 1993. The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America’s Man-Made Landscape. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Leyshon, Andrew, David Matless, and George Revill (eds.). 1998. The Place of Music. New York: Guilford.

McDowell, Linda (ed.). 1997. Undoing Place? A Geographical Reader. London: Arnold.

Naughton, Keith. 2004. “China Hits the Road.” Newsweek, 28 June, p. E22.

Nemeth, David J. 2000. “The End of the Re(li)gion?” North American Geographer 2: 1-8.

O’Loughlin, John, et al. 1998. “The Diffusion of Democracy, 1946-1994.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 88: 545-574.

Pew Charitable Trusts. 2013. Who’s Winning the Clean Energy Race? 2012 Edition. http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2013/04/17/whos-winning-the-clean-energy-race-2012-edition.

Pew Research Center. 2013. The New Sick Man of Europe: The European Union. http://www.pewglobal.org/files/2013/05/Pew-Research-Center-Global-Attitudes-Project-European-Union-Report-FINAL-FOR-PRINT-May-13-2013.pdf.

Poon, Jessie P. H., Edmund R. Thompson, and Philip F. Kelly. 2000. “Myth of the Triad? The Geography of Trade and Investment Blocs.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 25: 427-444.

Press, Larry. 1997. “Tracking the Global Diffusion of the Internet.” Communications of the Association of Computing Machinery 40(11): 11-17.

Relph, Edward. 1976. Place and Placelessness. London: Pion.

Rohter, Larry. 2002. “Brazil’s Prized Exports Rely on Slaves and Scorched Land.” The New York Times, 25 March, pp. A1, A6.

Sessions, George (ed.). 1995. Deep Ecology for the 21st Century. Boulder, Colo.: Shambala.

Shields, Rob. 1991. Places on the Margin: Alternative Geographies of Modernity. London: Routledge.

Sparke, Matthew. 2013. Introducing Globalization: Ties, Tensions, and Uneven Integration. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

Stiglitz, Joseph. 2007. Making Globalization Work. New York: W.W. Norton.

Suvantola, Jaakko. 2002. Tourist’s Experience of Place. Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate.

Swerdlow, Joel L. (ed.). 1999. “Global Culture.” Special issue of National Geographic 196(2): 2-132.

Swyngedouw, Erik. 1997. “Neither Global nor Local.” In Kevin R. Cox (ed.), Spaces of Globalization: Reasserting the Power of the Local, pp. 137-166. New York: Guilford.

490

Teo, Peggy, and Lim Hiong Li. 2003. “Global and Local Interactions in Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research 30(2): 287-306.

“Used and Abused: Five Recent Cases with Slavery Convictions.” 2003. Palm Beach Post, 7 December, p. 2.

Wood, William B. 2001. “Geographic Aspects of Genocide: A Comparison of Bosnia and Rwanda.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 26: 57-75.

Woods, Michael. 2012. “Rural Geography III: Rural Futures and the Future of Rural Geography.” Progress in Human Geography 36(1): 125-134.

York, Christopher. 2013. “Marine Le Pen, France’s Front National Leader, Claims Political Links With Nigel Farage’s UKIP.” Huffington Post UK. February2.http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2013/02/20/marine-le-penukip_n_2723386.html.

Zelinsky, Wilbur. 2011 Not Yet a Placeless Land: Tracking an Evolving American Geography. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Ten Recommended Books on the Geography of the Future

(For additional suggested readings, see the Contemporary Human Geography LaunchPad: http://www.macmillanhighered.com/launchpad/DomoshCHG1e.)

Appadurai, Arjun. 2013. The Future as Cultural Fact: Essays on the Global Condition. London: Verso. Using primarily examples from India, a renowned anthropologist presents essays on the past and future of the poor in a globalizating world. Features extended commentary on nationalism, violence, commodification, and terror.

Bagchi-Sen, Sharmistha, and Helen Smith (eds.). 2006. Economic Geography: Past, Present and Future. London: Routledge. Economic geographers point the way for the future development of the subfield in 20 wide-ranging chapters.

Firebaugh, Glenn. 2003. The New Geography of Global Inequality. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Makes the argument that income inequalities among and within world regions are misunderstood. There are a lot of economic data to wade through, but they make the case stronger. The author raises important questions about the effects of globalization.

Gabel, Medard, and Henry Bruner. 2003. Global Inc.: An Atlas of the Multinational Corporation. New York: New Press. A wonderful atlas mapping everything from the historical rise of multinational companies to the latest geographic expansions of Walmart. It’s full of facts on every important global industry, including food, cars, and pharmaceuticals. It also maps the impacts of multinational corporations, including cultural and environmental ones.

Gornitz, Vivien. 2013. Rising Seas: Past, Present, Future. New York: Columbia University Press. A sobering survey of the evidence for and likely future impacts of accelerating sea-level rise in the twenty-first century. The book provides an indispensable foundation for understanding the future of coastal landscapes and nature-culture interactions.

Hastrup, Kirsten, and Karen Fog Olwig (eds.). 2012. Climate change and human mobility: global challenges to the social sciences. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. Geographers and anthropologists bring a range of perspectives in an attempt to understand the effects of climate change on future human migrations. The collection includes cases from the Arctic, Pacifica, and Africa.

Johnston, R. J., Peter Taylor, and Michael Watts (eds.). 2002. Geographies of Global Change: Remapping the World. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell. Considers such issues as post-cold war geopolitics, global environmental governance, and cultural changes related to mass consumption, the Internet, and ethnic identity.

Jussila, Heikki, Roser Majoral, and Fernanda Delgado-Cravidao. 2001. Globalization and Marginality in Geographical Space. Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate. Case studies from Europe, the Americas, Africa, and Australia illustrate how geographical research aids our understanding of the way in which the policies and politics of globalization affect the more marginalized areas of the world.

Miles, Malcolm, and Tim Hall (eds.). 2003. Urban Futures: Critical Commentaries on Shaping Cities. London: Routledge. This volume brings together experts from a range of disciplines to debate the cultures and forms of tomorrow’s cities.

Schmidt, Eric, and Jared Cohen. 2013. The New Digital Age—Reshaping the Future of People, Nations, and Business. New York: Knopf. Eye-opening look at the new digital technologies just around the corner and what their introduction means for human affairs. Written by industry insiders, it reflects a modernist ideology that technology will deliver a better future for all.