CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

1.5

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Explain the concept of cultural landscape.

Our fifth and final theme is cultural landscape. The human or cultural landscape is made up of all the built forms that cultural groups create in inhabiting the Earth— roads, agricultural fields, cities, houses, parks, gardens, commercial buildings, and so on. Every inhabited area has a cultural landscape, fashioned from the natural landscape, and each uniquely reflects the culture or cultures that created it (Figure 1.15). Landscape mirrors a culture’s needs, values, and attitudes toward the Earth, and the human geographer can learn much about a group of people by carefully observing and studying the landscape. Indeed, so important is this visual record of cultures that some geographers regard landscape study as geography’s central interest.

cultural landscape

The visible human imprint on the land.

When the membership of the United Nations initiated the system of World Heritage Sites, it was a clear signal that landscape is universally valued as an expression of culture and identity. World Heritage Sites simultaneously celebrate both the vast diversity of cultural achievements worldwide and also the singular impulse to creatively manipulate the material environment that unites all humanity. Since the program’s establishment, countries have lobbied hard to receive World Heritage Site status for their landscapes and take pride in the global recognition of local cultural achievement. Members pledge precious government resources to forever protect landscapes within their borders and to respond with emergency assistance when threats to sites arise in any other member state.

29

Why is such importance attached to the human landscape? Perhaps part of the answer is that it visually reflects the most basic strivings of humankind: shelter, food, and clothing. In addition, the cultural landscape reveals people’s different attitudes toward the modification of the Earth. It also contains valuable evidence about the origin, spread, and development of cultures because it usually preserves various types of archaic forms. Dominant and alternative cultures use, alter, and manipulate landscapes to express their diverse identities (Figure 1.16).

33

Aside from containing archaic forms, landscapes also convey revealing messages about their present-day inhabitants and cultures. According to geographer Pierce Lewis, “The cultural landscape is our collective and revealing autobiography, reflecting our tastes, values, aspirations, and fears in tangible forms.” Cultural landscapes offer “texts” that geographers read to discover dominant ideas and prevailing practices within a culture as well as less dominant and alternative forms within it. This “reading,” however, is often a very difficult task, given the complexity of cultures, cultural change, and recent globalizing trends that can obscure local histories.

Geographers have pushed the idea of “reading” the landscape further to focus on the symbolic and ideological qualities of landscape. In fact, as geographer Denis Cosgrove has suggested, the very idea of landscape itself was ideological, in that its development in the Renaissance served the interests of the new elite class for whom agricultural land was valued not for its productivity but for its use as a visual subject. Land, in other words, was important to look at as a scene, and the actual activities necessary for agriculture were thus hidden from these views. If you go to an art museum, for example, it will be difficult, if not impossible, to find in the Italian Renaissance room any landscape paintings that depict agricultural laborers (Figure 1.17).

Closer to home, we need only to look outside our windows to see other symbolic and ideological landscapes. One of the most familiar and obvious symbolic landscapes is the urban skyline. Composed of tall buildings that normally house financial service industries, it represents the power and dominance of finance and economics within that culture (Figure 1.18). However, other cities are dominated by tall structures that have little to do with economics but more with religion. In medieval Europe, for example, cathedrals and churches rose high above other buildings, symbolizing the centrality and dominance of Catholicism in this culture (Figure 1.19).

symbolic landscapes

Landscapes that express the values, beliefs, and meanings of a particular culture

Even the most mundane landscape element can be interpreted as symbolic and ideological. The typical, middle-class, suburban, American or Canadian home, for example, expresses a dominant set of ideas about culture and family structure (Figure 1.20). These homes often include a living room, dining room, kitchen, and bedrooms, all separated by walls. The cultural assumptions built into this division of space are the assumed value of individual privacy (everyone has his or her own bedroom); the idea that certain functions should be spatially separate from others (cooking, eating, socializing, sleeping); and the notion that a family is composed of a mother, father, and children (indicated by the “master” bedroom and smaller “children’s” bedrooms). Thus, even the most common of landscapes can be seen as symbolic of a particular culture and built from ideological assumptions.

34

As we have seen, the physical content of the cultural landscape is both varied and complex. To better study and understand these complexities, geographical studies focus on three principal aspects of landscape: settlement forms, land-division patterns, and architectural styles. In the study of settlement forms, human geographers describe and explain the spatial arrangement of buildings, roads, and other features that people construct while inhabiting an area. One of the most basic ways in which geographers categorize settlement forms is to examine their degree of nucleation, a term that refers to the relative density of landscape elements. Urban centers are of course very nucleated, whereas rural farming areas tend to be much less nucleated, what geographers call dispersed. Another common way to think about settlement forms is the degree to which they appear standardized and planned, such as the grid form of much of the American West (Figure 1.21), versus the degree to which the forms appear to be organic, that is, built without any apparent geometric plan, such as the central areas of most European cities. Thinking about settlement forms in terms of these two basic categories helps geographers begin their analysis of the relationships between cultures and the landscapes they produce.

settlement forms

The spatial arrangement of buildings, roads, towns, and other features that people construct while inhabiting an area.

nucleation

A relatively dense settlement form.

dispersed

A type of settlement form in which people live relatively distant from each other.

Land-division patterns indicate the uses of particular parcels of land and, as such, reveal the way people have divided the land for economic, social, and political uses. Within a particular nucleated settlement form—a city, for example—you can see different patterns of land use. Some areas are devoted to economic uses, others to residential, political (city hall, for example), social, and cultural uses. Each of these areas can be further divided. Economic uses may include offices for financial services, retail stores, warehouses, and factories. Residential areas are often divided into middle-class, upper-class, and working-class districts and/or are grouped by ethnicity and race (see Chapter 10). Such patterns, of course, vary a great deal from place to place and culture to culture, as we will see throughout this book. One of the best ways to glimpse settlement and land-division patterns is through an airplane window. Looking down, you can see the multicolored abstract patterns of planted fields, as vivid as any modern painting, and the regular checkerboard or chaotic tangle of urban streets.

land-division patterns

Refers to the spatial patterns of different land uses.

Perhaps no other aspect of the human landscape is as readily visible from ground level as the architectural style of a culture. Geographers look at the exterior materials and decoration, as well as the layout and design of the interiors. Styles tend to vary both through time, as cultures change, and across space, in the sense that different cultures adopt and invent their own stylistic detailing according to their own particular needs, aesthetics, and desires. Thus, examining architectural style is often useful when trying to date a particular landscape element or to understand the particular values and beliefs that cultures may hold. In North American culture, different building styles catch the eye: modest white New England churches and giant urban cathedrals, hand-hewn barns and geodesic domes, wooden one-room schoolhouses and the new windowless school buildings of urban areas, shopping malls and glass office buildings. Each tells us something about the people who designed, built, or inhabit these spaces. Thus, architecture provides a vivid record of the resident culture (Figure 1.22). For this reason, cultural geographers have traditionally devoted considerable attention to examining architecture and style in the cultural landscape.

35

Subject To Debate: HUMAN ACTIVITIES AND GLOBAL CLIMATE CHANGE

Subject To Debate

HUMAN ACTIVITIES AND GLOBAL CLIMATE CHANGE

One of the most important and vexing scientific and political issues of the early twenty-first century is understanding the causes of recent global climate change and deciding what policies to pursue to lessen its effects. It’s also an issue that human geographers, with their emphasis on understanding nature-culture relationships, are well prepared to discuss.

According to a report by the National Academies of the United States (a joint body made up of the National Academy of Science, the National Academy of Engineering, the Institute of Medicine, and the National Research Council), the Earth’s temperatures are rising. Since the early twentieth century, the surface temperature of the Earth has risen 1.4°F, with the greatest increase occurring since 1978. Global climate, of course, is always changing. What is critical today, however, is the degree to which scientists have been able to correlate global warming trends with the rise in the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide is one of several greenhouse gases that keep radiative energy (and therefore warmth) trapped in the Earth’s atmosphere. It occurs naturally in the atmosphere but is also released when fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas are burned. Changes in the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, therefore, lead to changes in the Earth’s temperature. Changes in temperature, in turn, lead to other changes in the environment, such as the melting of glacial caps and the rising of sea levels.

To what degree are our activities—particularly our energy demands that lead to the burning of fossil fuels— responsible for this climate change? This is where the real debate starts. Some scientists are wary of pointing the finger at carbon dioxide emissions as the primary culprit, arguing along several lines that it is far from certain whether human activities have had such impacts on the Earth’s climate. Some are critical of the data that show increases in surface temperature. Some believe that the recent fluctuation in climate is a far more natural occurrence than one induced by humans. And some believe that the Earth’s atmospheric and climatic systems are simply so complex that it is premature to isolate one factor. Yet, there is growing worldwide consensus that human activities—particularly our reliance on the burning of fossil fuels—are the primary factors responsible for recent global warming. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a group of scientists from many different countries, concluded that because of the increase in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, by 2100 average temperatures on the surface of the Earth are likely to rise between 2.5°F and 10.4°F above 1990 levels. The question for this group of scientists is not what is causing these changes but what to do about it. The first step, these scientists argue, is to find ways to decrease levels of carbon dioxide released by looking to new technologies and alternative energy sources. But because the changes in climate are already occurring, the second step is finding ways to deal with the effects of global warming.

Geography is a discipline well suited to addressing this debate because, as we have seen, one of its primary activities is understanding nature-culture relationships. Figuring out to what degree, how, and why human activities interact with our physical environment is clearly the heart of what is being disputed here.

Continuing the Debate

As geographers, we know that various cultures interact with the environment differently and have varied beliefs and ideas about the role of science in explaining physical phenomena. Keeping this all in mind, consider these questions:

How might such cultural differences affect people’s conclusions about the causes and effects of global climate change?

How are your ideas about global climate change impacted by your position in the world?

30

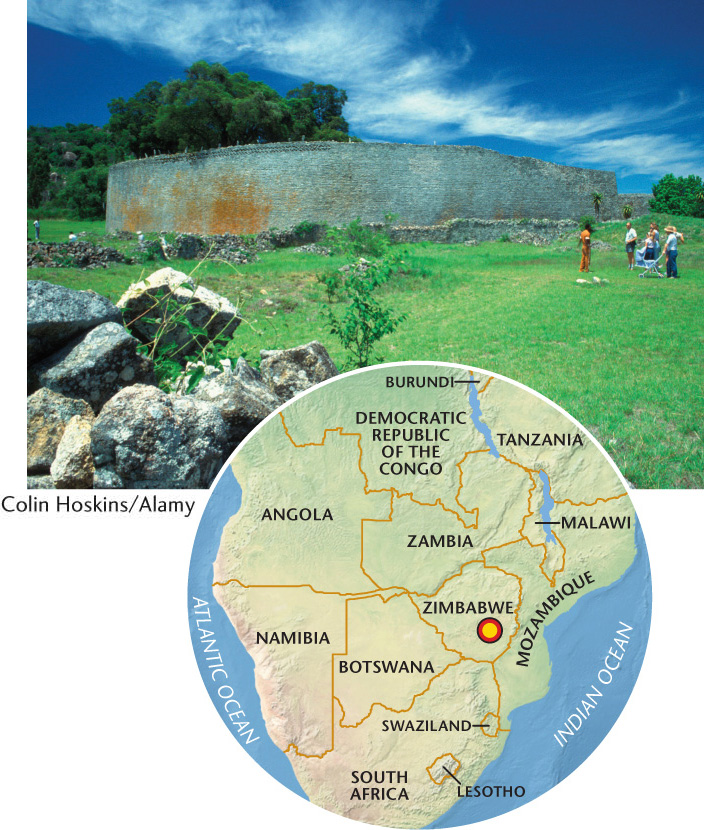

World Heritage Site: The Great Zimbabwe National Monument

World Heritage Site

The Great Zimbabwe National Monument

The Great Zimbabwe National Monument was constructed between 1100 and 1450 C.E. and encompasses over 700 hectares in a region populated by the Shona people of Zimbabwe. Placed on the list of World Heritage Sites in 1986, Great Zimbabwe contains the best example of African architecture south of the Sahara.

In the section known as the Great Enclosure, imposing dry masonry stone walls rise 11 meters, enclosing numerous dwellings and other stone structures. In addition to the Great Enclosure, two other distinct zones comprise the complex: the Hill Ruins and the Valley Ruins.

For nearly four centuries, the site served as the principle city of the Kingdom of Zimbabwe, housing 10,000 to 20,000 residents and functioning as the center of an international trading network that stretched across the Indian Ocean and, ultimately, to China. The kingdom ruled over a gold-rich plateau covering a portion of present-day Zimbabwe and Mozambique. Locally mined gold was smelted at the site into ingots for trade with coastal cities, which imported porcelain, glass beads, and other luxury goods.

Racist nineteenth-century theories of history prevented Europeans from recognizing the ruins as the grand achievement of an African civilization. They wildly speculated that ancient Phoenicians, Egyptians, and even the Queen of Sheba had built it. Even in the 1970s, the white-minority government of Zimbabwe (then Southern Rhodesia) officially denied the site’s black African origins. Twentieth-century archaeological studies have confirmed that the Shona’s ancestors built and continuously occupied the site for nearly four centuries.

In the context of the twentieth-century pan-African struggle against European colonialism and white-minority rule, the site came to serve as a key source of cultural pride among black Africans across the continent. It is symbolically important in the formation of both Shona ethnic identity and postcolonial Zimbabwean national identity. Indeed, the present-day country of Zimbabwe took its name from the site and adopted the Zimbabwean bird as its national symbol after gaining independence from white-minority rule in 1980.

Built between 1100 and 1450 C.E. by the Shona people of Zimbabwe, the site is a unique example of African architecture.

There are three main areas to the site: the Great Enclosure, the Hill Ruins, and the Valley Ruins.

Placed on the list of World Heritage Sites in 1986, the site has been visited by thousands of tourists, but tourism has slowed due to political and economic instability in the country.

whc.unesco.org/en/list/364

31

THE GREAT ENCLOSURE: The most remarkable feature of the site is the Great Enclosure, an area dominated by a monumental, oval-shaped outer wall spanning 250 meters in length and 3 meters in width. The craftsmanship of this area is stunning, beginning with the skillful splitting of granite blocks excavated from a nearby quarry. The granite split easily along fracture planes, resulting in cubelike blocks that were stacked and fitted together after craftsmen carefully smoothed the surfaces. This technique resulted in a finished quality that rivals modern brick walls and allowed the stone city to be built without mortar, yet remain intact for centuries.

Cut stones set in herringbone and chevron patterns accent the top of the outer wall. Within the wall are a smaller stone enclosure and a narrow stone passageway leading to the beehive-shaped conical tower. The tower is constructed of solid stone blocks and assumed to have had a primarily symbolic or ceremonial purpose.

The enclosure once contained houses built of clay and gravel, of which only traces remain. These were organized into walled-off community areas composed of a kitchen, dwelling huts, and a court. One key theory suggests that the enclosure contained the royal residence of the kingdom’s ruler. Thus, the Great Enclosure represents the seat of political and economic power for the expansive Zimbabwe kingdom.

TOURISM: The site is readily accessible and also relatively close to other attractions such as Victoria Falls (another World Heritage Site) and many of southern Africa’s wildlife parks.

International tour companies include it on their packaged travel itineraries. Visitors freely roam the site and explore the very different perspectives and features offered by the Great Enclosure, the Hill Ruins, and Valley Ruins.

Political and economic instability in the country, however, has resulted in a significant drop-off in tourist activity in Zimbabwe. Although ruinous to the local economy, the lull in tourist traffic may be giving this archeological wonder a needed respite from overuse.

32