MOBILITY

2.2

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Describe the ways that mobility interacts with cultural difference.

The movement of things, ideas, and people shapes and is shaped by geography. For example, things and people in motion can minimize the relevance of nation-state borders or nation-state borders can greatly restrict mobility. The interactions of geography and mobility are complex and not altogether predictable.

VAMPIRE TOURISTS

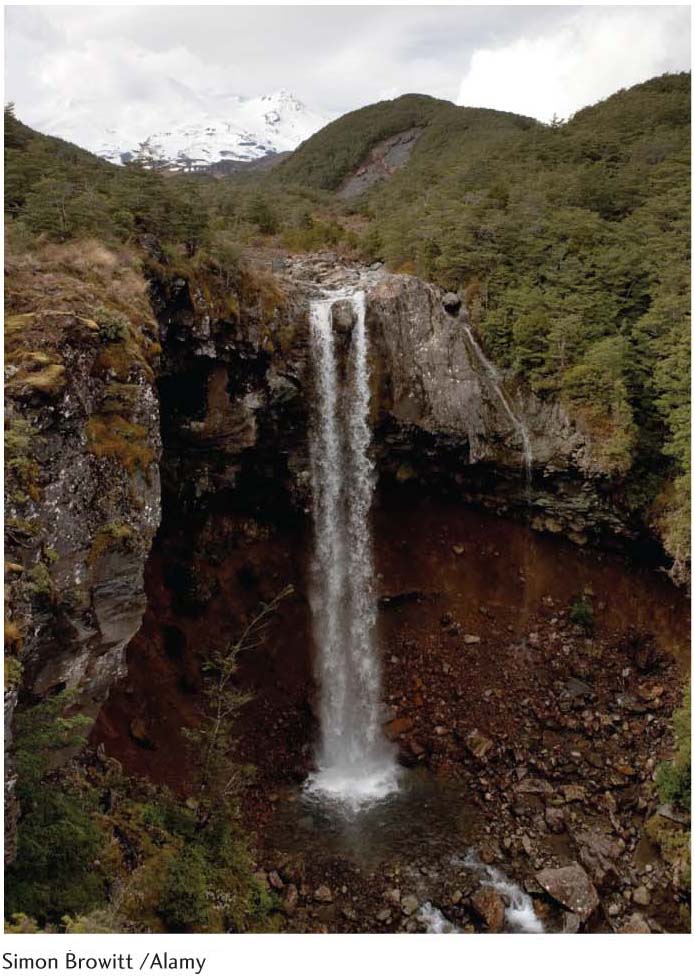

No other practice better exemplifies mobility in popular culture than tourist travel. And no form of tourist travel provides a more surprising blend of reality and fiction, folk and popular culture, than vampire tourism. According to geographer Duncan Light, vampire tourism is a form of “media tourism,” a practice whereby fans of a fictional story or character—whether portrayed in a novel, film, or television program—travel to key places and landscapes in the plot. The New Zealand locations of the Lord of the Rings film series, for example, have become a key destination for the country’s foreign tourists (Figure 2.31).

Vampires are popping up everywhere in popular culture. They appear in novels and cinema (the Twilight series), animated feature films (Hotel Transylvania), graphic novels (Interview with the Vampire: Claudia’s Story), and cable television (Vampire Diaries). So saturated is popular culture with vampire stories that one would be hard pressed to find a mass entertainment medium in which they do not materialize. Interestingly, the undead lives of these ubiquitous blood suckers are anchored in real geography, resulting in the rapid growth in vampire tourism nationally and globally. The Lonely Planet, a well-known publisher of travel guides, features a list of the “world’s best vampire-spotting locations” on its web site.

62

Fictional vampire characters appear in the most unexpected places, including Forks, Washington; New Orleans, Louisiana; Volterra, Italy; and Mystic Falls, Virginia. Actually, Mystic Falls, the setting for the Vampire Diaries, is fictional, too, but the television show is shot in real-life Covington, Georgia. Entrepreneurs in Covington have wasted no time creating “Mystic Falls” tour packages. As one web site advertises, “The Mystic Falls Tour is the perfect destination for travelers looking for a memorable Vampire Diaries adventure.” Forks, Washington, where the Twilight series is based, has been overrun by hundreds of tourists daily—many of them young women around the age of Bella’s character—a phenomenon that has significantly improved the fortunes of this economically depressed logging town.

The Curse of Dracula, Revisited Forks and Covington, however, are mere way stations on the pilgrimage route to the mecca of vampire tourism, the Transylvania region of Romania (Figure 2.32). Transylvania is home to the world’s most famous vampire, Count Dracula, subject of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula and of the numerous subsequent film versions. Dracula already had an international reputation—the novel has been translated into numerous languages—when Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 film Bram Stoker’s Dracula made the count a global personality. Stoker loosely based Dracula on vampire folktales that circulated throughout southeastern Europe in the eighteenth century. In his novel, Stoker located the count’s home in Transylvania’s Dran Castle, which makes it a global destination for vampire tourists (Figure 2.33). Ironically, no folk tradition of vampirism exists in the region’s culture. This inconvenient fact did not prevent Stoker from vaguely modeling Count Dracula on Vald III (or Vlad Ţepeş), a real-life Transylvanian ruler from the 1450s whom the Romanians revere as a nationalist hero for his role in repelling an Ottoman Turkish invasion.

Light shows in his study The Dracula Dilemma how vampire tourism raises difficult questions for the Romanian government and its citizens on issues of national and cultural identity. The Dracula story, Light points out, positions Romania as a backward, superstitious region on the eastern margins of modern, civilized western Europe. Moreover, Stoker links the evil beast Dracula, who is threatening the English homeland, to Vlad III, a heroic figure in the creation of Romanian cultural and national identity. Imagine the world outside the United States believing George Washington was a vampire. In short, Stoker’s character casts Romania in a negative light and challenges its citizens’ national identity at its deepest level. Dracula is an awkward figure around which to build a Romanian tourist industry.

Cashing In on the Count Until 1989 Romania was a communist country where government censorship of popular media, including the Dracula stories, was widespread. When the country abandoned communism, it lifted censorship and unleashed private entrepreneurship. Stoker’s novel and Coppola’s film began to circulate widely in Romania. The borders were opened up to the global tourist industry. Businesses started trading on the Dracula name, which is used to market guesthouses, restaurants, and even beer and cigarettes (Figure 2.34). The main marketing target is foreign tourists arriving to visit the “home” of Dracula.

63

The Romanian government and many citizens were not as quick as entrepreneurs to embrace Stoker’s portrayal of Transylvania. As Light points out, the Romanian nation-state wishes “to project a sense of its own political and cultural identity to the wider world on its own terms.” Those terms are defined by a desire to be politically and economically integrated into the European Union while maintaining a distinct and proud cultural heritage. The ironies and frustrations of being the nation and culture most identified with Dracula are manifold, not least being the fact that no tradition of vampires exists in Romanian folklore. According to Light, Romanians do not and never did believe in vampires, but the whole world thinks of Transylvania as the home of the most infamous vampire of all.

European Union

The union of 28 European countries established through a set of political, cultural, and economic treaties and supranational institutions.

Vampire tourism illustrates a number of features of mobility in popular culture. There is the mobility of the vampire myth; the ways it is transported and transplanted from folk to popular culture; the ways it circulates globally, linking unlikely places as distant and dissimilar as Forks and Transylvania; and the ways it has set people in motion in search of direct experiences with these places. Fictional characters move through factual landscapes and consequently affect real-life political, economic, and cultural relations through media tourism. The mobility of vampire tourists following fictional plot lines, as Light emphasizes for Romania, “illustrates global inequalities and asymmetries in cultural power.” The Romanian government and citizenry have fought a losing battle for control over representation of their cultural heritage. In popular culture, Transylvania appears doomed to an undying association with a superstition transported from folk traditions rooted in far-off places.

64

IDENTITY IN DIASPORA CULTURE

Diaspora cultures are, by definition, born of mobility. Civil war and international armed conflicts over the past two generations have set millions of people in motion around the world, creating many new diaspora cultures. The list is long and includes the Cuban diaspora (following the 1959 communist revolution in Cuba), the Hmong diaspora (following the U.S.-Vietnam War in 1975), and the Sudanese diaspora (following civil wars ongoing since the 1980s). The civil wars in Sudan displaced at least 4 million people, creating a new diaspora located on three different continents (Figure 2.35). Major armed conflict in Sudan developed around the economic, religious, cultural, and racial differences distinguishing the Arabic/Islamic northern region, where the military and government were centered, from the African/Christian southern region, where rich oil deposits are found. Thus, a significant portion of the diaspora are southerners fleeing the fighting between the northern military and southern insurgents. The United States has been among the largest receiver countries, taking in approximately 150,000 southern Sudanese. Major Sudanese diaspora concentrations are located in Minnesota, New York, and Texas.

The Sudanese Diaspora and the Establishment of South Sudan Geographer Caroline Faria conducted research among the Sudanese diaspora communities in the United States to investigate how members forge cultural and national identities under conditions of displacement. Faria’s study of the Sudanese diaspora took place during a critical historical juncture, ranging from the 2005 signing of a peace agreement to the establishment in 2011 of South Sudan, the world’s newest nation-state (Figure 2.36). It was during this period that the diaspora community vigorously debated what a new nation should be and what it would mean, culturally, to be a South Sudanese citizen.

65

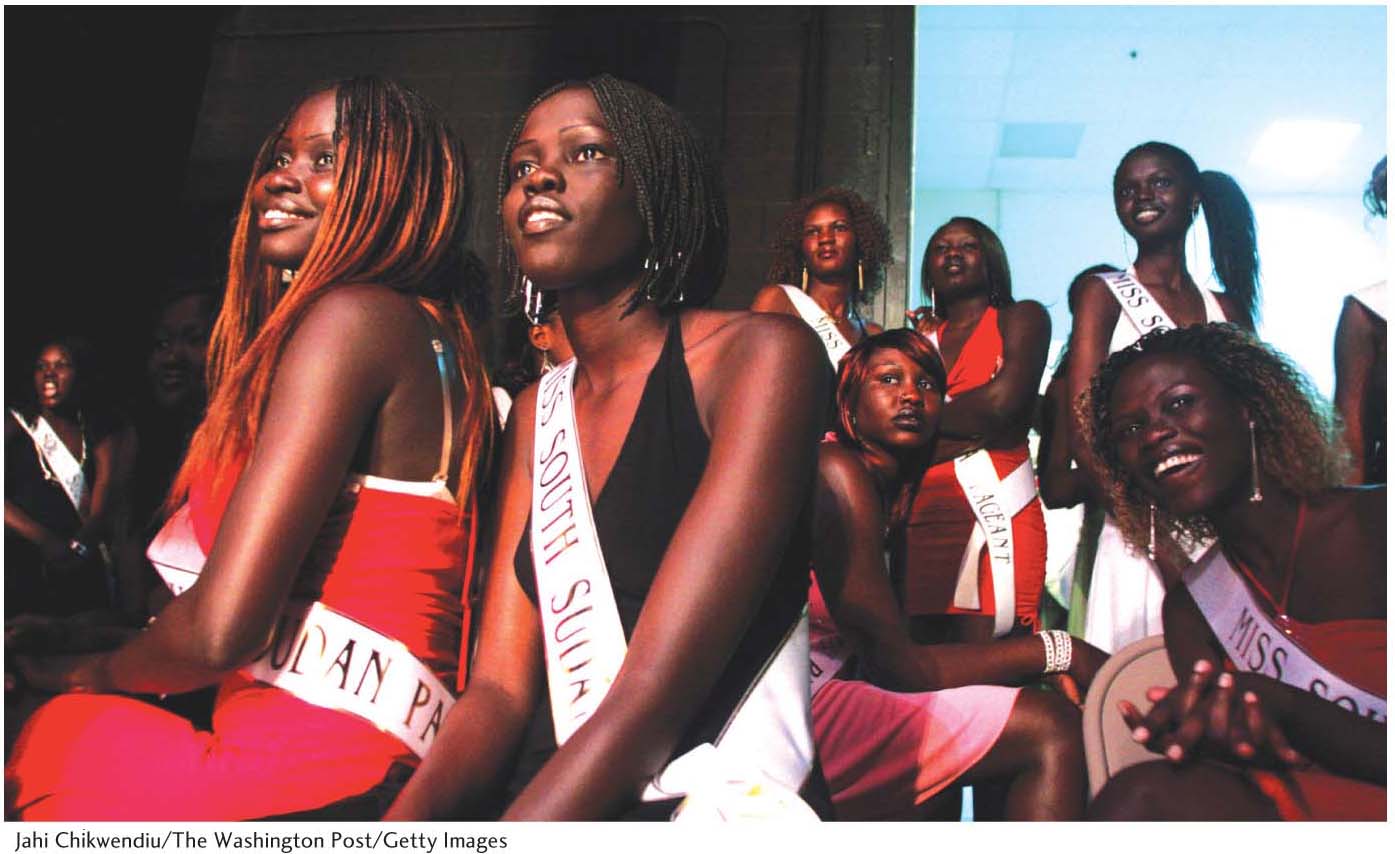

Faria analyzed the first and second “Miss South Sudan” contests held in Washington, D.C., in 2006 and Kansas City in 2007 to demonstrate the importance of diasporic beauty pageants for “promoting and imagining a distant home and nation.” Beauty pageants, in general, are fruitful sites for studying debates around gender, race, and national identity because the contest winner is assumed to represent, even embody, the essential qualities of the nation. Thus in the Miss South Sudan contests, organizers, participants, and spectators struggled to identify an ideal type of woman who would signify the new nation.

As Faria discovered after analyzing interviews and public commentary and debate, the ideal South Sudanese woman must conform to certain racial, religious, and gender identities. First, differences in religious beliefs both supported and were accentuated by the north-south armed conflict in Sudan. Christianity has become an important marker of difference to distinguish southern Sudanese cultural identity from the north. Miss South Sudan pageant commentators and judges thus emphasized “a strong Christian Faith as a vital part of any perspective winner.” Second, southern Sudan is imagined as “culturally and pheno-typically oriented toward Sub-Saharan Africa while the North is associated with an Arab influence and a lighter skin tone.” Consequently, participants and judges in the Miss South Sudan contests linked the notion of feminine beauty to “blackness,” with the 2006 winner opting for the “natural” look of a simple hair weave that projected a more “African” identity for the new nation (Figure 2.37). Finally, the pageant exposed an unresolved contradiction in the Sudanese diaspora’s ideas of womanhood and women’s ideal role in the new South Sudan nation. Contestants were expected on the one hand to delay marriage and aspire to higher education and professional careers, while on the other to maintain a traditional role as mothers who would reproduce the new nation.

The case of the Miss South Sudan pageants highlights the challenge facing many diaspora cultures around the world: how to establish a coherent identity under conditions of displacement and uncertainty. In imagining national and cultural identities from a distance, diaspora cultures must confront basic questions about national ideals of masculinity and femininity and the relationship of race and religion to nationhood. Showcases of national culture, such as beauty pageants, are not merely sources of popular entertainment. Rather, they are cultural cauldrons in which national identities are cemented, reproduced, and reimagined.

BARRIERS TO INFORMATION MOBILITY

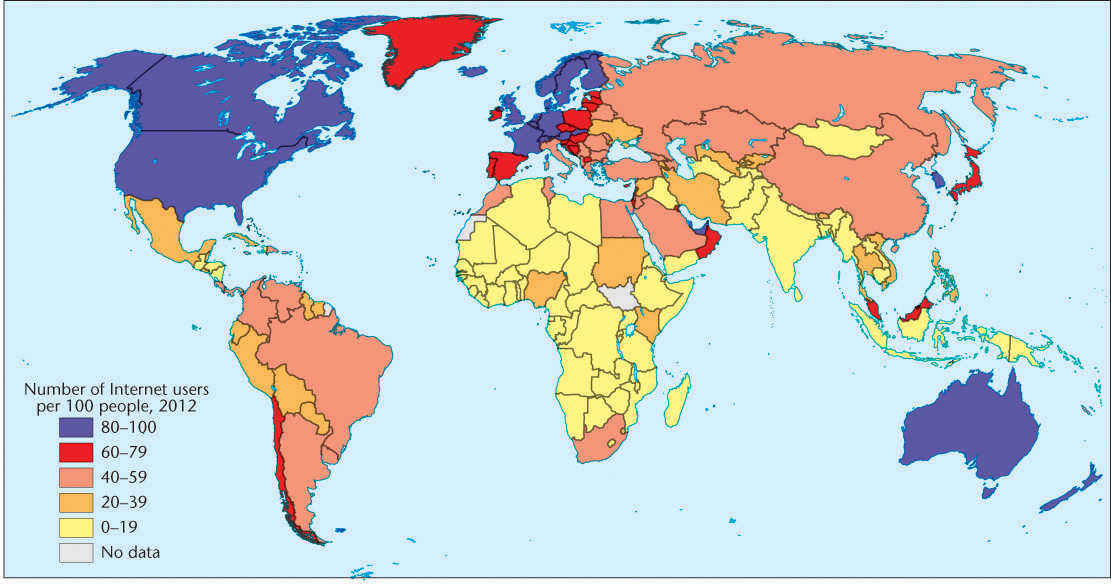

Although mass media create the potential for the almost instant diffusion of information over very large areas, this potential can be greatly impeded and slowed if access is limited or denied. Access to the Internet is a case in point. Though older forms of mass communication, such as television and newspapers, are unlikely to disappear, an increasing proportion of people worldwide turn to the Internet. The shift in technology has created a so-called digital divide between those who have ready access to the Internet information stream and those who have limited or no access (Figure 2.38). Many factors contribute to the digital divide, but one of the most basic is lack of Internet infrastructure in many parts of the world. Thus, while information may diffuse globally on the Internet at near light speed, it is irrelevant to those without a computer and the infrastructure to connect. A historical analogy might be the invention of the printing press when most of the world’s population was illiterate.

66

digital divide

A pattern of unequal access to advanced information technologies produced by socioeconomic inequalities and measured at scales ranging from the individual to countries and world regions.

Recognition of the digital divide and potential solutions have arisen and spread quickly, precisely because information moves around the globe at great speed. New initiatives meant to address the gap spring up continually. For example, the Digital Divide Institute operates as a policy think tank to advise companies and governments on solutions and Pew Research conducts surveys on who does and does not use the Internet and why. The Internet has both exacerbated socioeconomic inequalities and allowed for a rapid response to try to correct them.

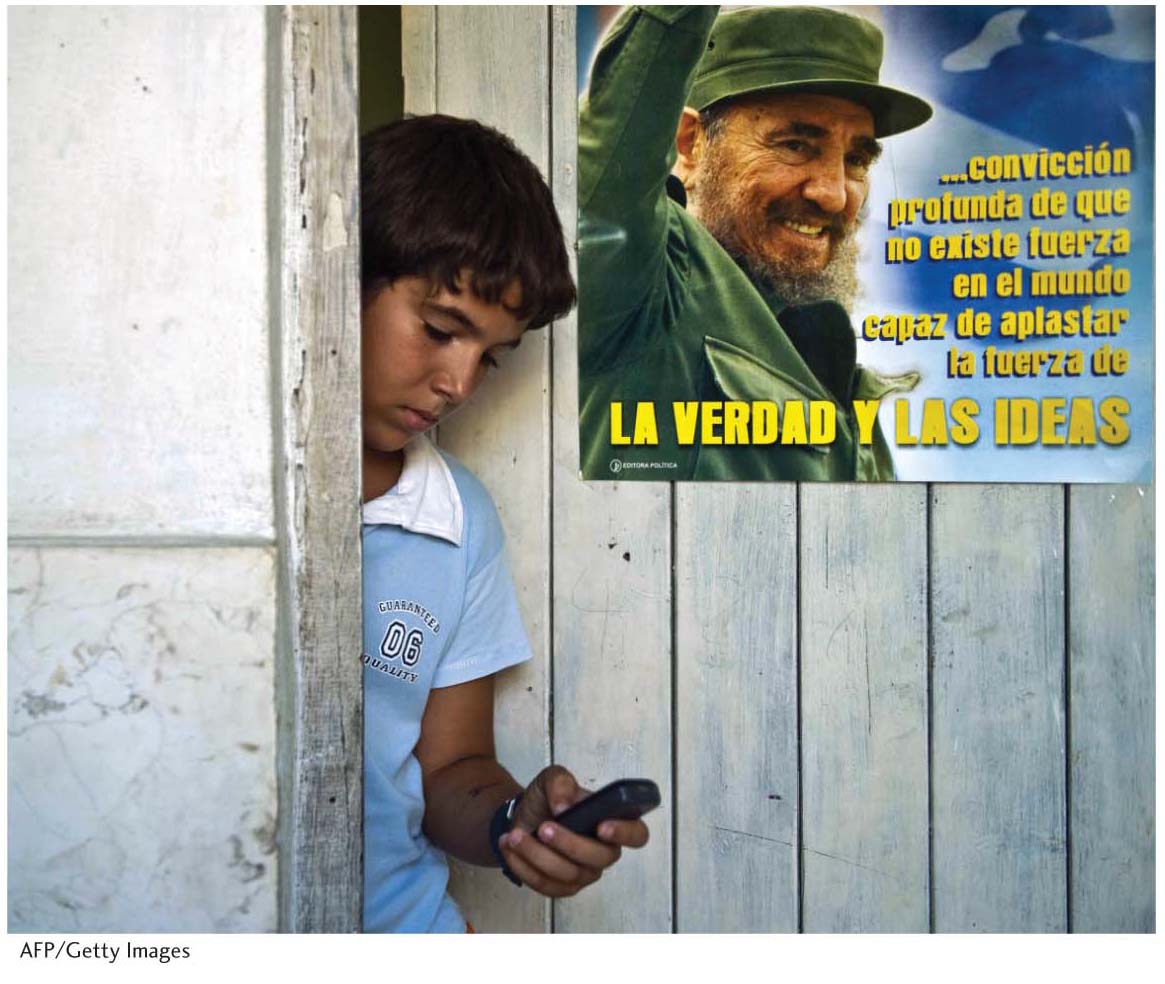

Governmental Bans on Technology In addition to the existing inequalities in Internet access, governments around the world periodically implement technology bans that have the effect of limiting the diffusion of information and ideas (Figure 2.39). For years Cuba banned cell phones, fearing that citizens would have access to information unfavorable to the government. A huge black market in cell phones forced the government to lift the ban in 2008. The government of the Czech Republic in 2010 banned the use of Google’s Street View technology over privacy concerns. It has since lifted the ban after negotiating very strict rules on how Google is allowed to use the technology. The United Arab Emirates briefly banned the BlackBerry in 2010 because the device’s encryption makes it difficult for governments to monitor content for what they consider objectionable material. Though all these bans were ultimately lifted, they suggest that governments will continue to try to limit or control the diffusion of information across nation-state borders.

67