MOBILITY

3.2

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Identify patterns, causes, and consequences of population migrations and things—such as diseases—that accompany them.

After natural increases and decreases in populations, the second of the two basic ways in which population numbers are altered is the migration of people from one place to another, and it offers a straightforward illustration of relocation diffusion. When people migrate, they sometimes bring more than simply their culture; they can also bring disease. The introduction of diseases to new places can have dramatic and devastating consequences. Thus, the spread of diseases is also considered as part of the theme of mobility because diseases move with people.

112

MIGRATION

Humankind is not tied to one locale. Homo sapiens most likely evolved in Africa, and ever since, we have proved remarkably able to adapt to new and different physical environments. We have made ourselves at home in all but the most inhospitable climates, avoiding only such places as ice-sheathed Antarctica and the shifting sands of the Arabian Peninsula’s “Empty Quarter.” Our permanent habitat extends from the edge of the ice sheets to the seashores, from desert valleys below sea level to high mountain slopes. This far-flung distribution is the product of migration.

Early human groups moved in response to the migration of the animals they hunted for food and the ripening seasons of the plants they gathered. Indeed, the agricultural revolution, whereby humans domesticated crops and animals and accumulated surplus food supplies, allowed human groups to stop their seasonal migrations. But, why did certain groups opt for long-distance relocation? Some migrated in response to environmental collapse, others in response to religious or ethnic persecution. Still others—probably the majority, in fact—migrated in search of better opportunities. For those who migrate, the process generally ranks as one of the most significant events of their lives.

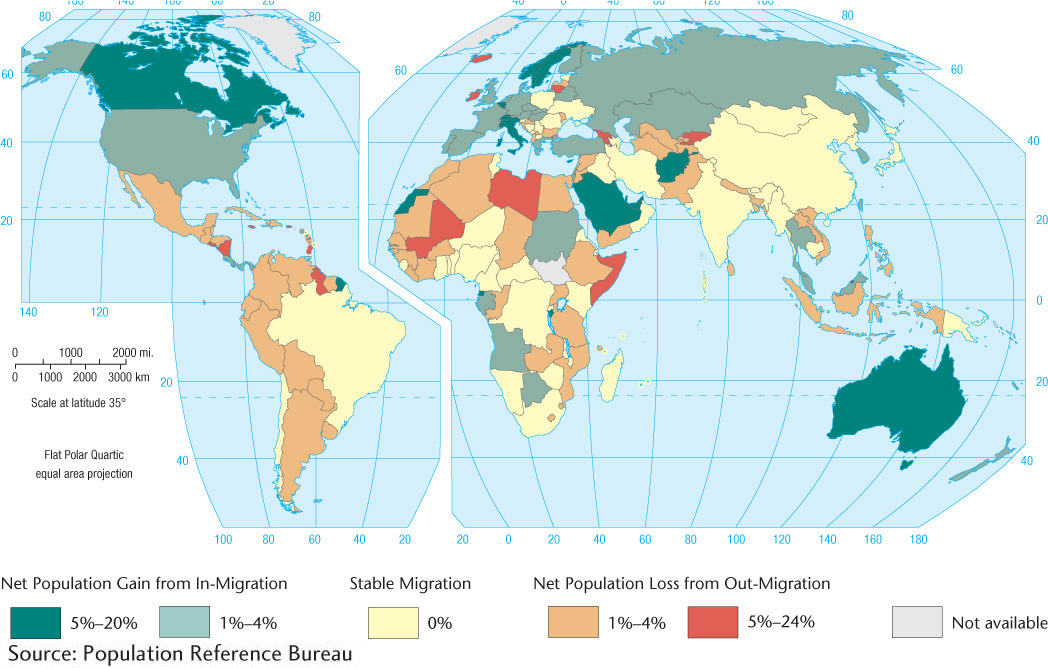

The Decision to Move Migration takes place when people decide that moving is preferable to staying and when the difficulties of moving seem to be more than offset by the expected rewards. In the nineteenth century, more than 50 million European emigrants left their homelands in search of better lives. Today, migration patterns are very different (Figure 3.17). Europe, for example, now predominantly receives immigrants rather than sending out emigrants. International migration stands at an all-time high, much of it labor migration associated with the process of globalization. About 215 million people today live outside the country of their birth.

Historically, and to this day, forced migration also often occurs. The westward displacement of the Native American population of the United States; the dispersal of the Jews from Palestine in Roman times and from Europe in the mid-twentieth century; the export of Africans to the Americas as slaves; and the Clearances, or forced removal, of farmers from Scotland’s Highlands to make way for large-scale sheep raising—all provide depressing examples. Today, refugee movements are far too common, prompted mainly by despotism, war, ethnic persecution, and famine. Recent decades have witnessed a worldwide flood of refugees: people who leave their country because of persecution based on race, ethnicity, religion, nationality, or political opinion (note that economic persecution does not fall under the definition of refugee). Perhaps as many as 16 million people who live outside their native country are refugees (see also Chapter 5).

refugees

Those fleeing from persecution in their country of nationality. The persecution can be religious, political, racial, or ethnic.

Every migration, from the ancient dispersal of humankind out of Africa to the present-day movement toward urban areas, is governed by a host of push-and-pull factors that act to make the old home unattractive or unlivable and the new land attractive. Generally, push factors are the most central. After all, a basic dissatisfaction with the homeland is prerequisite to voluntary migration. The most important factor prompting migration throughout the thousands of years of human existence has been economic. More often than not, migrating people seek greater prosperity through better access to resources, especially land. Both forced migrations and refugee movements, however, challenge the basic assumption of the push-and-pull model, which posits that human movement is the result of choices and is primarily driven by economic factors.

push-and-pull factors

Unfavorable, repelling conditions (push factors) and favorable, attractive conditions (pull factors) that interact to affect migration and other elements of diffusion.

DISEASES ON THE MOVE

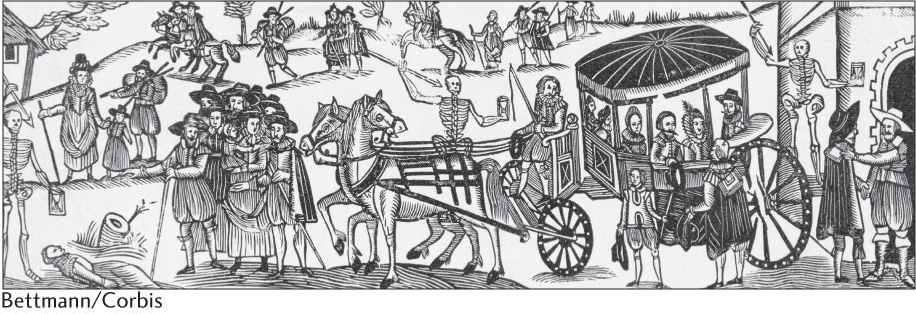

Throughout history, infectious disease has periodically decimated human populations. One has only to think of the vivid accounts of the Black Death episodes that together killed one-third of medieval Europe’s population to get a sense of how devastating disease can be. Importantly for cultural geographers, diseases both move in spatially specific ways and result in responses that are spatial in nature.

113

The spread of disease provides classic illustrations of both expansion and relocation diffusion. Some diseases are noted for their tendency to expand outward from their points of origin. Commonly borne by air or water, the viral pathogens for contagious diseases such as influenza and cholera spread from person to person throughout an affected area. Some diseases spread in a hierarchical diffusion fashion, whereby only certain social strata are exposed. The poor, for example, have always been much more exposed to the unsanitary conditions—rats, fleas, excrement, and crowding—that have led to disease epidemics. Other illnesses, particularly airborne diseases, affect all social and economic classes without regard for human hierarchies: their diffusion pattern is literally contagious. Indeed, disease and migration have long enjoyed a close relationship. Diseases have spread and relocated thanks to human movement. Likewise, widespread human migrations have occurred as the result of disease outbreaks.

When humans engage in long-distance mobility, their diseases move along with them. Thus, cholera—a waterborne disease that had for centuries been endemic to the Ganges River region of India— broke out in the early 1800s in Calcutta (now called Kolkata; see Figure 4.21 and Seeing Geography). Because Calcutta was an important node in Britain’s colonial empire, cholera quickly began to relocate far beyond India’s borders. Soldiers, pilgrims, traders, and travelers spread cholera throughout Europe, then from port to port across the world through relocation diffusion, making cholera the first disease of global proportions.

114

Early responses to contagious diseases were often spatial in nature. Isolation of infected people from the healthy population—known as quarantine—was practiced. Sometimes only the sick individuals were quarantined, whereas at other times households or entire villages were shut off from outside contact. Whole shiploads of eastern European immigrants to New York City were routinely quarantined in the late nineteenth century. Another early spatial response was to flee the area where infection had occurred. During the time of the plague in fourteenth-century Europe, some healthy individuals abandoned their ill neighbors, spouses, and even children. Some of them formed altogether separate communities, whereas others sought merely to escape the city walls for the countryside (Figure 3.18).

Targeted spatial strategies could be implemented once it became known that some diseases spread through specific means. The best-known example is John Snow’s 1854 mapping of cholera outbreaks in London, illustrated in Figure 3.19, which allowed him to trace the source of the infection to one water pump. Thanks to his detective work, and the development of a broader medical understanding of the role of germs in the spread of disease, cholera was discovered to be a waterborne disease that could be controlled by increasing the sanitary conditions of water delivery.

115

The threat of deadly disease is hardly a thing of the past. Today, geographers play vital roles in understanding the diffusion of HIV/AIDS, SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), and the so-called swine flu and bird flu in order to better address outbreaks and halt the spread of these global scourges. By mapping the spread of these contemporary diseases, understanding the pathways traveled by their carriers, and developing appropriate spatial responses, it is hoped that mass epidemics and disease-related panics can be avoided.