REGION

4.1

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Understand the geographical patterning of languages.

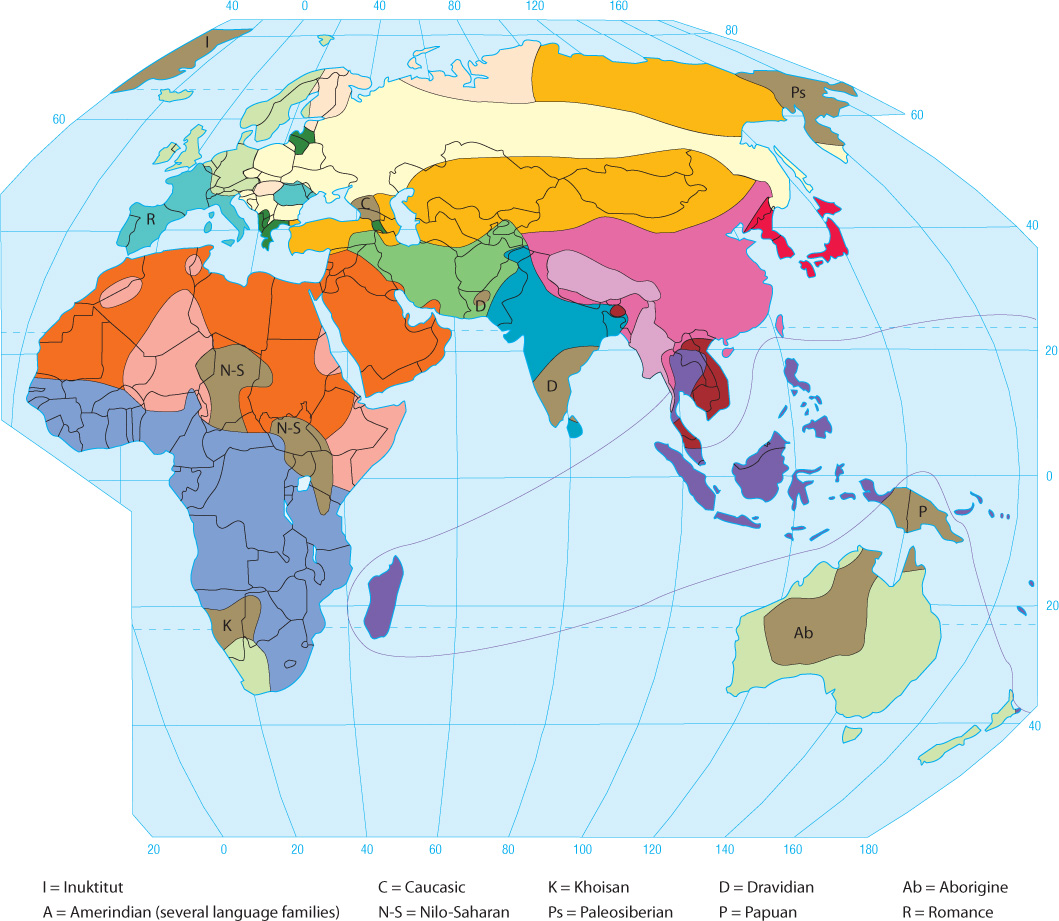

The spatial variation of speech is remarkably complicated, adding intricate patterns to the human mosaic (Figure 4.2). Because language is such a central component of culture, understanding the spatiality of language, and how and why its patterns change over time, provides a particularly valuable window into cultural geography more generally. The logical place to begin our geographical study of language is with the regional theme.

Separate languages are those that cannot be mutually understood. In other words, a monolingual speaker of one language cannot comprehend the speaker of another. Dialects, by contrast, are variant forms of a language where mutual comprehension is possible. A speaker of English, for example, can generally understand that language’s various dialects, regardless of whether the speaker comes from Australia, Scotland, or Mississippi. Nevertheless, a dialect is distinctive enough in vocabulary and pronunciation to label its speaker as hailing from one place or another, or even from a particular city. About 7000 languages and many more dialects are spoken in the world today.

dialect

A distinctive local or regional variant of a language that remains mutually intelligible to speakers of other dialects of that language; a subtype of a language.

139

When different linguistic groups come into contact, a pidgin language, characterized by a very small vocabulary derived from the languages of the groups in contact, often results. Pidgins primarily serve the purposes of trade and commerce: they facilitate exchange at a basic level but do not have complex vocabularies or grammatical structures. An example is Tok Pisin, meaning “talk business.” Tok Pisin is a largely English-derived pidgin spoken in Papua New Guinea, where it has become the official national language in a country where many native Papuan tongues are spoken. Although New Guinea pidgin is not readily intelligible to a speaker of Standard English, certain common words such as gut bai (“good-bye”), tenkyu (“thank you”), and haumas (“how much”) reflect the influence of English. When pidgin languages acquire fuller vocabularies and become native languages of their speakers, they are called creole languages. Obviously, deciding precisely when a pidgin becomes a creole language has at least as much to do with a group’s political and social recognition as it does with what are, in practice, fuzzy boundaries between language forms.

pidgin

A composite language consisting of a small vocabulary borrowed from the linguistic groups involved in commerce.

creole

A language derived from a pidgin language that has acquired a fuller vocabulary and become the native language of its speakers.

140

141

Another response to the need for speakers of different languages to communicate with one another is the elevation of one existing language to the status of a lingua franca. A lingua franca is a language of communication and commerce spoken across a wide area where it is not a mother tongue. The Swahili language enjoys lingua franca status in much of East Africa, where inhabitants speak a number of other regional languages and dialects. English is fast becoming a global lingua franca. Finally, regions that have linguistically mixed populations may be characterized by bilingualism, which is the ability to speak two languages with fluency. For example, along the U.S.-Mexico border, so many residents speak both English and Spanish (with varying degrees of fluidity) that bilingualism in practice—even if not in policy—means there is no need for a lingua franca.

lingua franca

An existing, well-established language of communication and commerce used widely where it is not a mother tongue.

bilingualism

The ability to speak two languages fluently.

142

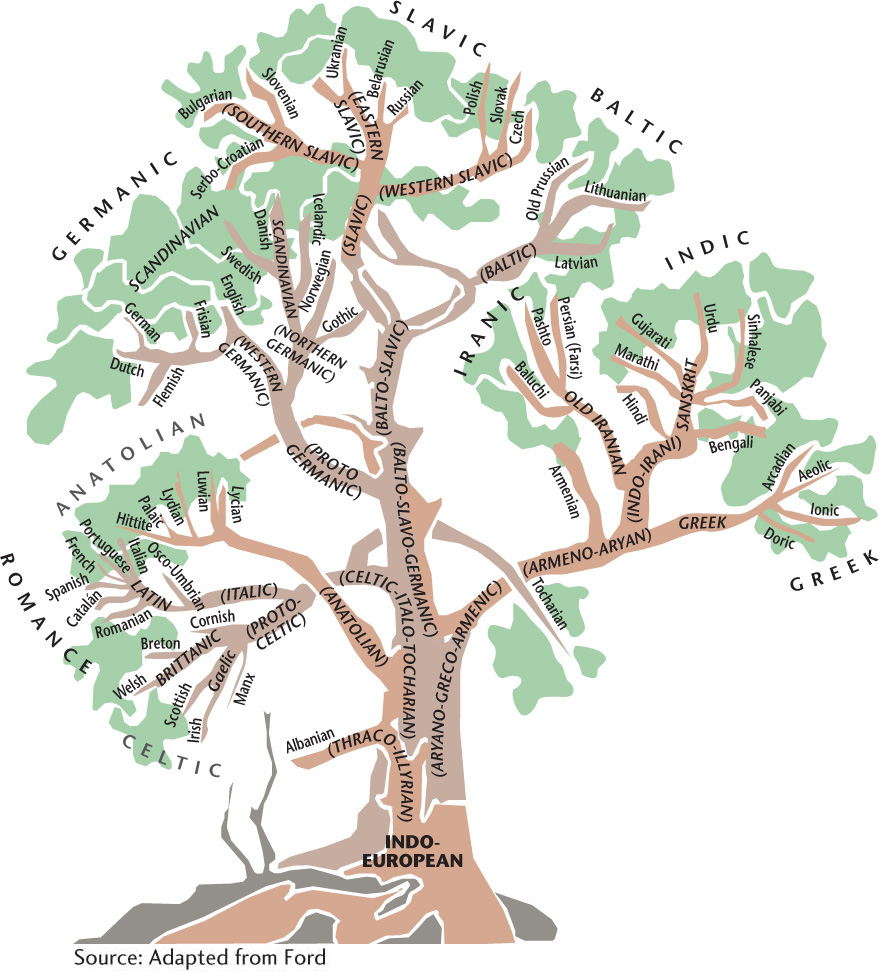

LANGUAGE FAMILIES

One way in which geolinguists often simplify the mapping of languages is by grouping them into language families: tongues that are related and share a common ancestor. Words are simply arbitrary sounds associated with certain meanings. Thus, when words in different languages are alike in both sound and meaning, they may well be related. Over time, languages interact with one another, borrowing words, imposing themselves through conquest, or organically diverging from a common ground. Languages and their interrelations can thus be graphically depicted as a tree with various branches (Figure 4.3). This classification makes the complicated linguistic mosaic a bit easier to comprehend.

language family

A group of related languages derived from a common ancestor.

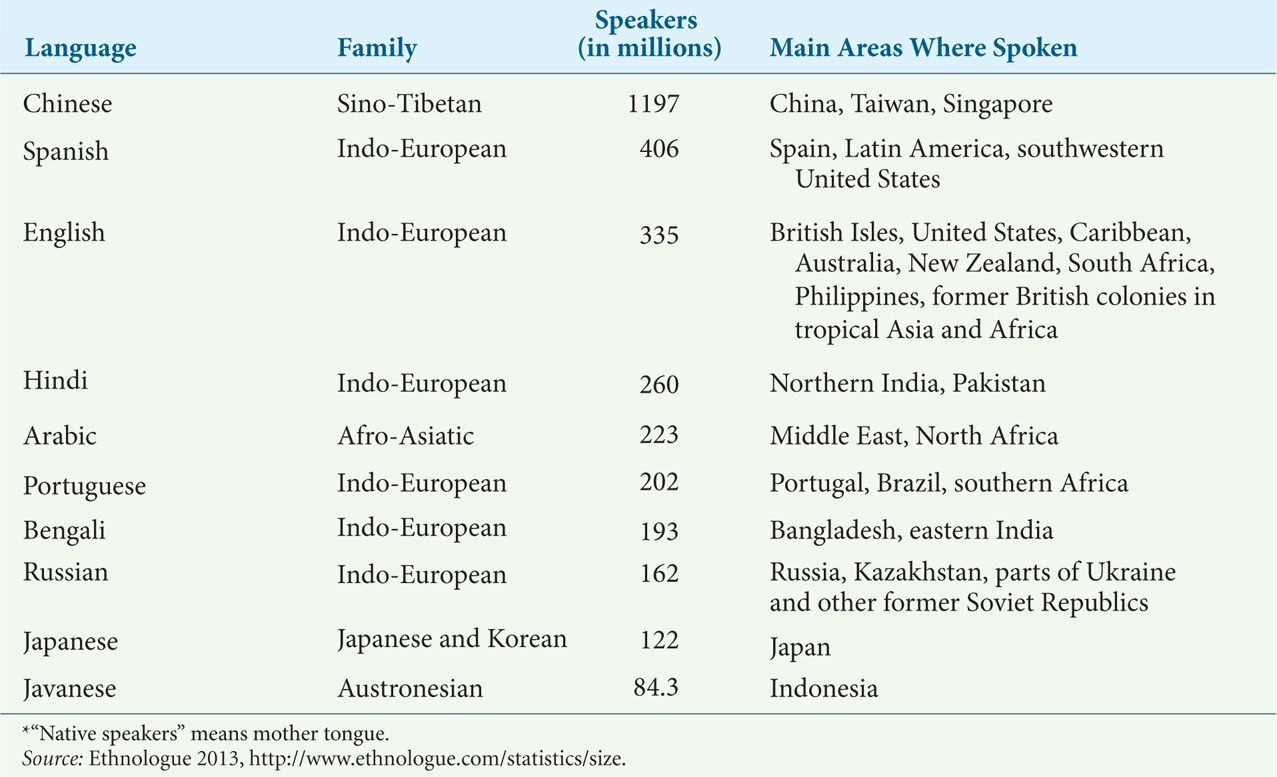

Indo-European Language Family The largest and most widespread language family is the Indo-European, which is spoken on all the continents and is dominant in Europe, Russia, North and South America, Australia, and parts of southwestern Asia and India (see Figure 4.3). Romance, Slavic, Germanic, Indic, Celtic, and Iranic are all Indo-European subfamilies. These subfamilies, in turn, are divided into individual languages. For example, English is a Germanic Indo-European language. Six Indo-European tongues, including English, are among the 10 most spoken languages in the world as classified by the number of native speakers (Table 4.2).

Comparing the vocabularies of various Indo-European tongues reveals their kinship. For example, the English word mother is similar to the Polish matka, the Greek meter, the Spanish madre, the Farsi madar in Iran, and the Sinhalese mava in Sri Lanka. Such similarities demonstrate that these languages have a common ancestral tongue.

Sino-Tibetan Family Sino-Tibetan is another of the major language families of the world and is second only to Indo-European in numbers of native speakers. The Sino-Tibetan region extends throughout most of China and Southeast Asia (see Figure 4.2). The two language branches that make up this group, Sino- and Tibeto-Burman, are believed to have had a common origin some 6000 years ago in the Himalayan Plateau; speakers of the two language groups subsequently moved along the great Asian rivers that originate in this area. “Sino” refers to China and in this context indicates the various languages spoken by more than 1.3 billion people in China. Han Chinese (Mandarin) is spoken in a variety of dialects and serves as the official language of China. The nearly 400 languages and dialects that make up the Burmese and Tibetan branch of this language family border the Chinese language region on the south and west. Other East Asian languages, such as Vietnamese, have been heavily influenced by contact with the Chinese and their languages, although it is not clear that they are linguistically related to Chinese at all.

143

Afro-Asiatic Family The third major language family is the Afro-Asiatic. It consists of two major divisions: Semitic and Hamitic. The Semitic languages cover the area from the Arabian Peninsula and the Tigris-Euphrates river valley of Iraq westward through Syria and North Africa to the Atlantic Ocean. Despite the considerable size of this region, there are fewer speakers of the Semitic languages than you might expect because most of the areas that Semites inhabit are sparsely populated deserts. Arabic is by far the most widespread Semitic language and has the greatest number of native speakers, about 223 million. Although many different dialects of Arabic are spoken, there is only one written form.

Hebrew, which is closely related to Arabic, is another Semitic tongue. For many centuries, Hebrew was a “dead” language, used only in religious ceremonies by millions of Jews throughout the world. With the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, a common language was needed to unite the immigrant Jews, who spoke the languages of their many different countries of origin. Hebrew was revived as the official national language of what otherwise would have been a polyglot, or multilanguage, state (Figure 4.4). Amharic, a third major Semitic tongue, is spoken today by 21 million in the mountains of East Africa.

polyglot

A mixture of different languages.

Smaller numbers of people who speak Hamitic languages share North and East Africa with the speakers of Semitic languages. Like the Semitic languages, these tongues originated in Asia but today are spoken almost exclusively in Africa by the Berbers of Morocco and Algeria, the Tuaregs of the Sahara, and the Cushites of East Africa.

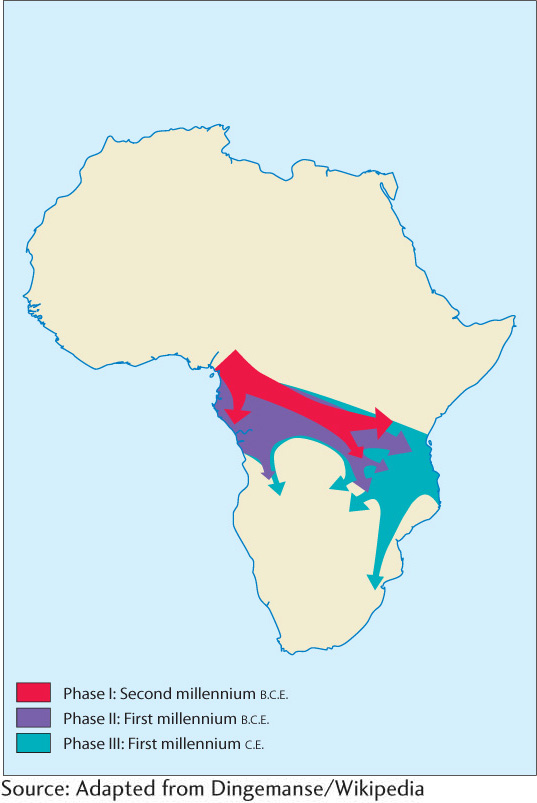

144

Other Major Language Families Most of the rest of the world’s population speak languages belonging to one of six remaining major families. The Niger-Congo language family, also called Niger-Kordofanian, which is spoken by about 430 million people, dominates Africa south of the Sahara Desert. The greater part of the Niger-Congo culture region belongs to the Bantu subgroup. Both Niger-Congo and its Bantu constituent are fragmented into a great many different languages and dialects, including Swahili. The Bantu and their many related languages spread from what is now southeastern Nigeria about 4000 years ago, first west and then south in response to climate change and new agricultural techniques (Figure 4.5).

Flanking the Slavic Indo-Europeans on the north and south in Asia are the speakers of the Altaic language family, including Turkic, Mongolic, and several other subgroups. The Altaic homeland lies largely in the inhospitable deserts, tundra, and coniferous forests of northern and central Asia. Also occupying tundra and grassland areas adjacent to the Slavs is the Uralic family. Finnish and Hungarian are the two more widely spoken Uralic tongues, and both enjoy the status of official languages in their respective countries.

One of the most remarkable language families in terms of distribution is the Austronesian. Representatives of this group live mainly on tropical islands stretching from Madagascar, off the east coast of Africa, through Indonesia and the Pacific islands, to Hawaii and Easter Island. This longitudinal span is more than half the distance around the world. The north-south, or latitudinal, range of this language area is bounded by Hawaii and Taiwan in the north and New Zealand in the south. The largest single language in this family is Javanese, with 84.3 million native speakers, but the most geographically widespread is Polynesian.

145

Japanese and Korean, with about 188.4 million speakers combined, probably form another Asian language family. The two perhaps have some link to the Altaic family, but even their kinship to each other remains controversial and unproven.

In Southeast Asia, the Vietnamese, Cambodians, Thais, and some tribal peoples of Malaya and parts of India speak languages that constitute the Austro-Asiatic family. They occupy an area into which Sino-Tibetan, Indo-European, and Austronesian languages have all encroached.