CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

4.5

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Identify the ways languages are visibly part of the cultural landscape.

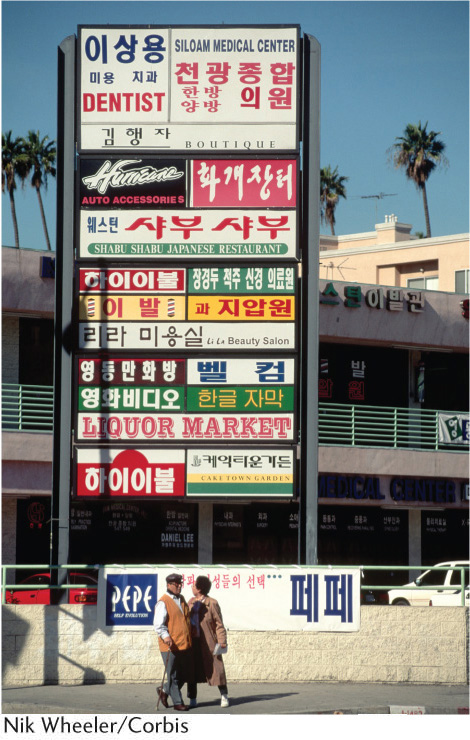

Road signs, billboards, graffiti, placards, and other publicly displayed writings not only reveal the locally dominant language but also can be a visual index to bilingualism, linguistic oppression of minorities, and other facets of linguistic geography. Furthermore, differences in writing systems render some linguistic landscapes illegible to those not familiar with these forms of writing (Figure 4.17).

MESSAGES

Linguistic landscapes send messages, both friendly and hostile. Often these messages have a political content and deal with power, domination, subjugation, or freedom. In Turkey, for example, until recently Kurdish-speaking minorities were not allowed to broadcast music or television programs in Kurdish, to publish books in Kurdish, or even to give their children Kurdish names. Because Turkey wishes to join the European Union, these minority language restrictions have come under intense outside scrutiny. In 2002 Turkey reformed its legal restrictions to allow the Kurdish language to be used in daily life but not in public education. In 2012 Kurdish language instruction became an elective subject in Turkey’s public schools. The Canadian province of Québec, similarly, has tried to eliminate English-language signs. French-speaking immigrants settled Québec, and its official language is French, in contrast to Canada’s policy elsewhere of bilingualism in English and French. As Figure 4.18 indicates, there is a movement in Ireland to replace English-language place-name signs with signs depicting the original Gaelic place-names. The suppression of minority languages and attempts to reinstate them in the landscape offer an indication of the social and political status of minority populations more generally.

163

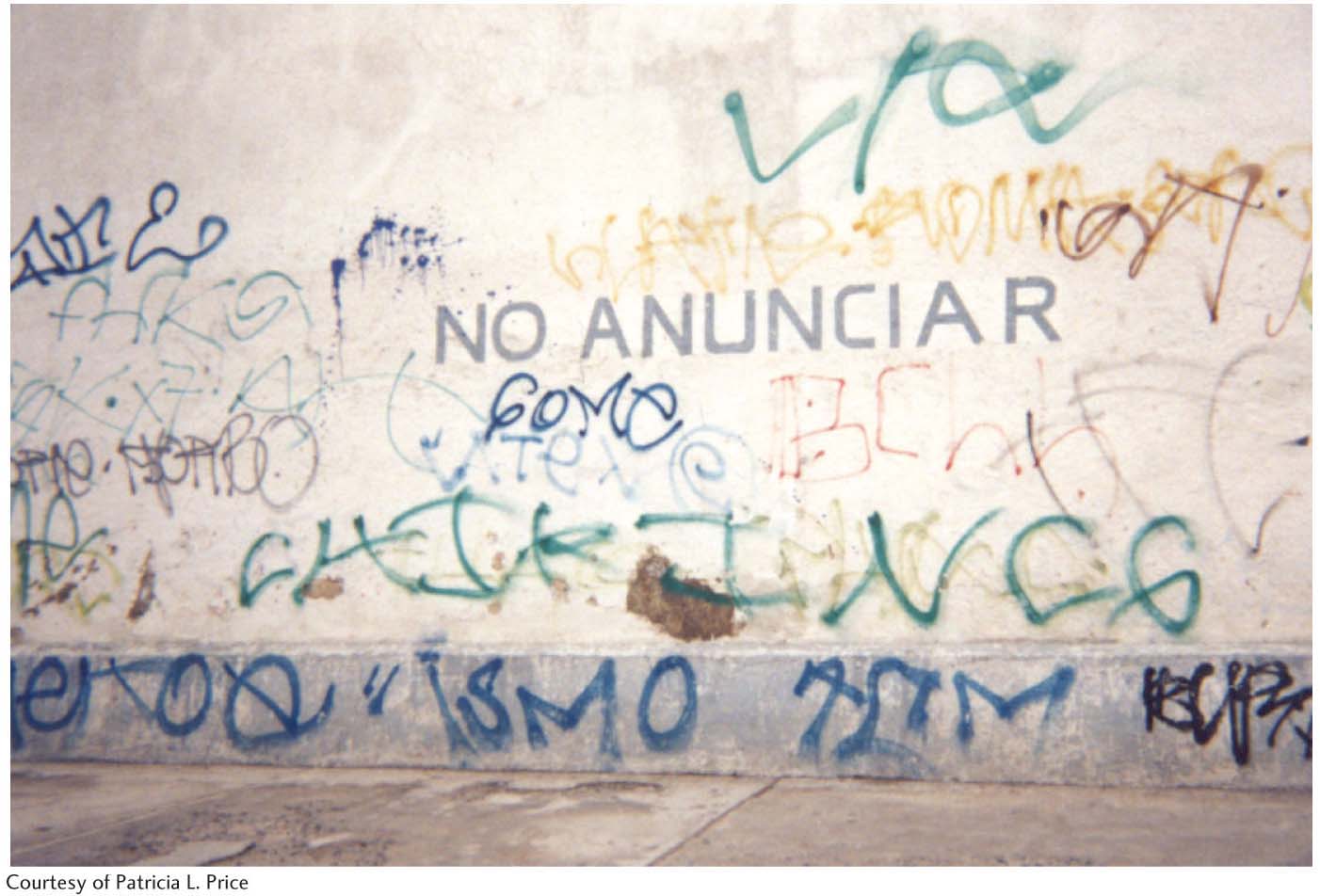

Other types of writing, such as gang-related graffiti, can denote ownership of territory or send messages to others that they are not welcome (Figure 4.19). Only those who understand the specific gang symbols used will be able to decipher the message. Misreading such writing can have dangerous consequences for those who stray into unfriendly territory. In this way, gang symbols can be understood as a dialect that is particular to a subculture and transmitted through symbols or a highly stylized script.

TOPONYMS

Language and culture also intersect in the names that people place on the land, whether they are given to settlements, terrain features, streams, or various other aspects of their surroundings. These place-names, or toponyms, often directly reflect the spatial patterns of language, dialect, and ethnicity. Toponyms become part of the cultural landscape when they appear on signs and placards. Many place-names consist of two parts—the generic and the specific. For example, in the American place-names Huntsville, Harrisburg, Ohio River, Newfound Gap, and Cape Hatteras, the specific segments are Hunts-, Harris-, Ohio, Newfound, and Hatteras. The generic parts, which tell what kind of place is being described, are -ville, -burg, River, Gap, and Cape.

toponym

A place-name usually consisting of two parts: the generic and the specific.

164

Generic toponyms are of greater potential value to the cultural geographer than specific names because they appear again and again throughout a culture region. There are literally thousands of generic place-names, and every culture or subculture has its own distinctive set of them. They are particularly valuable both in tracing the spread of a culture and in reconstructing culture regions of the past. Sometimes generic toponyms provide information on changes people brought about long ago in their physical surroundings.

generic toponym

The descriptive part of many place-names, often repeated throughout a culture area.

GENERIC TOPONYMS OF THE UNITED STATES

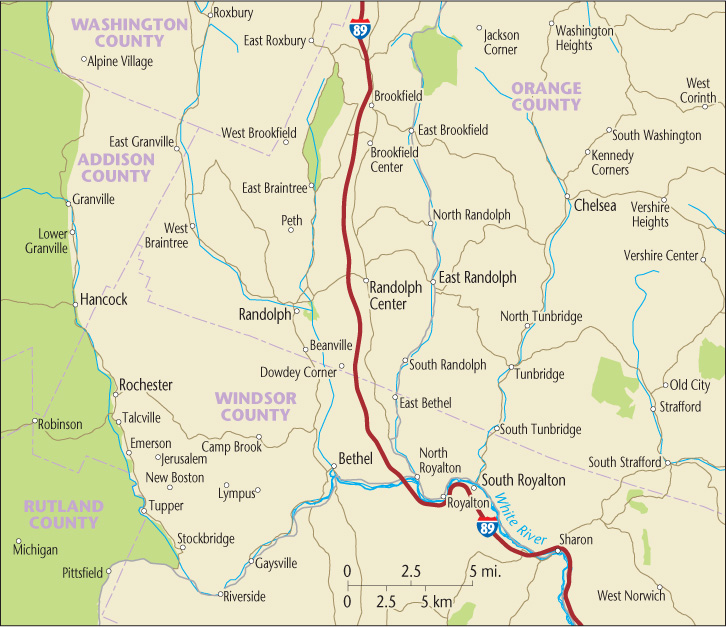

The three dialects of the eastern United States (see Figure 4.8)—Northern, Midland, and Southern—illustrate the value of generic toponyms in cultural geographical detective work. For example, New Englanders, speakers of the Northern dialect, often used the terms Center and Corners in the names of the towns or hamlets. Outlying settlements frequently bear the prefix East, West, North, or South, with the specific name of the township as the suffix. Thus, in Randolph Township, Orange County, Vermont, we find settlements named Randolph Center, South Randolph, East Randolph, and North Randolph (Figure 4.20). A few miles away lies Hewitts Corners.

These generic usages and duplications are peculiar to New England, and we can locate areas settled by New Englanders as they migrated westward by looking for such place-names in other parts of the country. A trail of “Centers” and name duplications extending westward from New England through upstate New York and Ontario and into the upper Midwest clearly indicates their path of migration and settlement. Toponymic evidence of New England exists in areas as far away as Walworth County, Wisconsin, where Troy, Troy Center, East Troy, and Abels Corners are clustered; in Dufferin County, Ontario, where one finds places such as Mono Centre; and even in distant Alberta, near Edmonton, where the toponym Michigan Centre doubly suggests a particular cultural diffusion. Similarly, we can identify Midland American areas by such terms as Gap, Cove, Hollow, Knob (a low, rounded hill), and -burg, as in Stone Gap, Cades Cove, Stillhouse Hollow, Bald Knob, and Fredericksburg. We can recognize southern speech by such names as Bayou, Gully, and Store (for rural hamlets), as in Cypress Bayou, Gum Gully, and Halls Store.

165

TOPONYMS AND CULTURES OF THE PAST

Place-names often survive long after the culture that produced them vanishes from an area, thereby preserving traces of the past. Australia abounds in Aborigine toponyms, even in areas from which the native peoples disappeared long ago. No toponyms are more permanently established than those identifying physical geographical features, such as rivers and mountains. Even the most absolute conquest, exterminating an aboriginal people, usually does not entirely destroy such names. Quite the contrary, in fact. Geographer R. D. K. Herman speaks of anticonquest, in which the defeated people finds its toponyms venerated and perpetuated by the conqueror, who at the same time denies the people any real power or cultural influence. The abundance of Native American toponyms in the United States provides an example (see Doing Geography). India, however, has recently decided to revert to traditional toponyms, after many Indian place-names had been Anglicized under British colonial rule (Figure 4.21).

In Spain and Portugal, seven centuries of Moorish rule left behind a great many Arabic place-names. An example is the prefix guada- on river names (as in Guadalquivir and Guadalupejo). The prefix is a corruption of the Arabic wadi, meaning “river” or “stream.” Thus, Guadalquivir, corrupted from Wadial-Kabir, means “the great river.” The frequent occurrence of Arabic names in any particular region or province of Spain reveals the remnants of Moorish cultural influence in that area, rather than anticonquest. Many such names were brought to the Americas through Iberian conquest, so that Guadalajara, for example, appears on the map as an important Mexican city.

Vigilante Copyeditor

![]() Vigilante Copyeditor

Vigilante Copyeditor

http://www.tinyurl.com/l5mxlpk

This video depicts vandalism of the Sculpture Park at Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute. The vandalism was not done by your run-of-the-mill vandal bent on destroying or defacing the sculptures. Instead, Pratt’s vandal has made it his (or her) job to correct the grammar on the sculpture placards. The narrator discusses how the edits to the text of the placards interact with the sculptures in a way that demonstrates critical thinking. Because the corrections are not signed, the identity of the “vigilante copyeditor” remains unknown.

Thinking Geographically:

This chapter discusses toponyms, or place-names, and notes that there are sometimes very contentious battles about what name a place should be given, and who should do the naming. Can you view what happened with the placards at the Sculpture Park as a battle over toponyms? How (or how not)?

What is the relationship between art and language in a public space such as Pratt’s Sculpture Park?

The video claims that most graffiti artists in Brooklyn “tattoo ... egocentric message[s]” on public spaces. Is this a fair assessment? In what ways was the work of the “vigilante copyeditor” different from—and the same as—that of other urban graffiti artists? What’s the difference between a graffiti artist and a vandal? What label would you assign to the individual (or individuals) who corrected the grammar on the placards at the Pratt Institute Sculpture Park, and why?

166

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF TOPONYMS

Without a doubt,you are familiar with places that bear the names of wealthy and influential individuals, politicians, or corporate sponsors. Sports stadiums, campus buildings, museums—all provide specific spaces that can be named. The owners of these spaces typically use naming opportunities as a way to raise funds. For instance, universities provide naming rights for donors contributing anywhere from $5 million to $20 million (Figure 4.22).

But, what happens when a place that has been built using public monies—say, a train station that was constructed using tax revenues—is given a corporate name (Figure 4.23)? Geographers Reuben Rose-Redwood and Derek Alderman examine this practice, using the example of the building that was constructed to replace the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers, which were destroyed in the terrorist attacks of 9/11. The building was initially dubbed “The Freedom Tower,” but once it acquired corporate tenants, the building began to be referred to by its legal address, One World Trade Center. According to Rose-Redwood and Alderman, this illustrates “how the naming of places has become . . . one of the next ‘frontiers’ in the neoliberalization of urban spaces” (2011, p. 2).

167

What happens when the corporate sponsor of a place has a less-than-acceptable reputation? Florida Atlantic University, for instance, sold the naming rights for its sports stadium to GEO Group for $6 million in February 2013. GEO Group operates private prisons and has been implicated in the inhuman treatment of inmates at its facilities. Less than two months later, the agreement was cancelled. In this instance, the negative place image cast by a shady corporate sponsor simply wasn’t worth the price paid.

Is no place safe from corporate ownership? Apparently not. People are paid to allow companies to use their cars as mobile billboards. What about the items of clothing and accessories that prominently bear the names of their designers? Is what poet Adrienne Rich called “the geography closest-in”—our bodies—a place that is also open for corporate naming opportunities?

168

World Heritage Site: Alhambra, Generalife, and Albayzín

World Heritage Site

Alhambra, Generalife, and Albayzín

The Alhambra fortress-palace complex, gardens and rural estates of the Generalife, and the Albayzín residential quarter together form this World Heritage Site. All three are located in the city of Granada, in southern Spain. The Alhambra and the Albayzín are situated on hills above the modern lower city. Hills were important defense sites in medieval European cities (see Chapter 10). And, the irrigated gardens of the Generalife were part of the rulers’ rural estates.

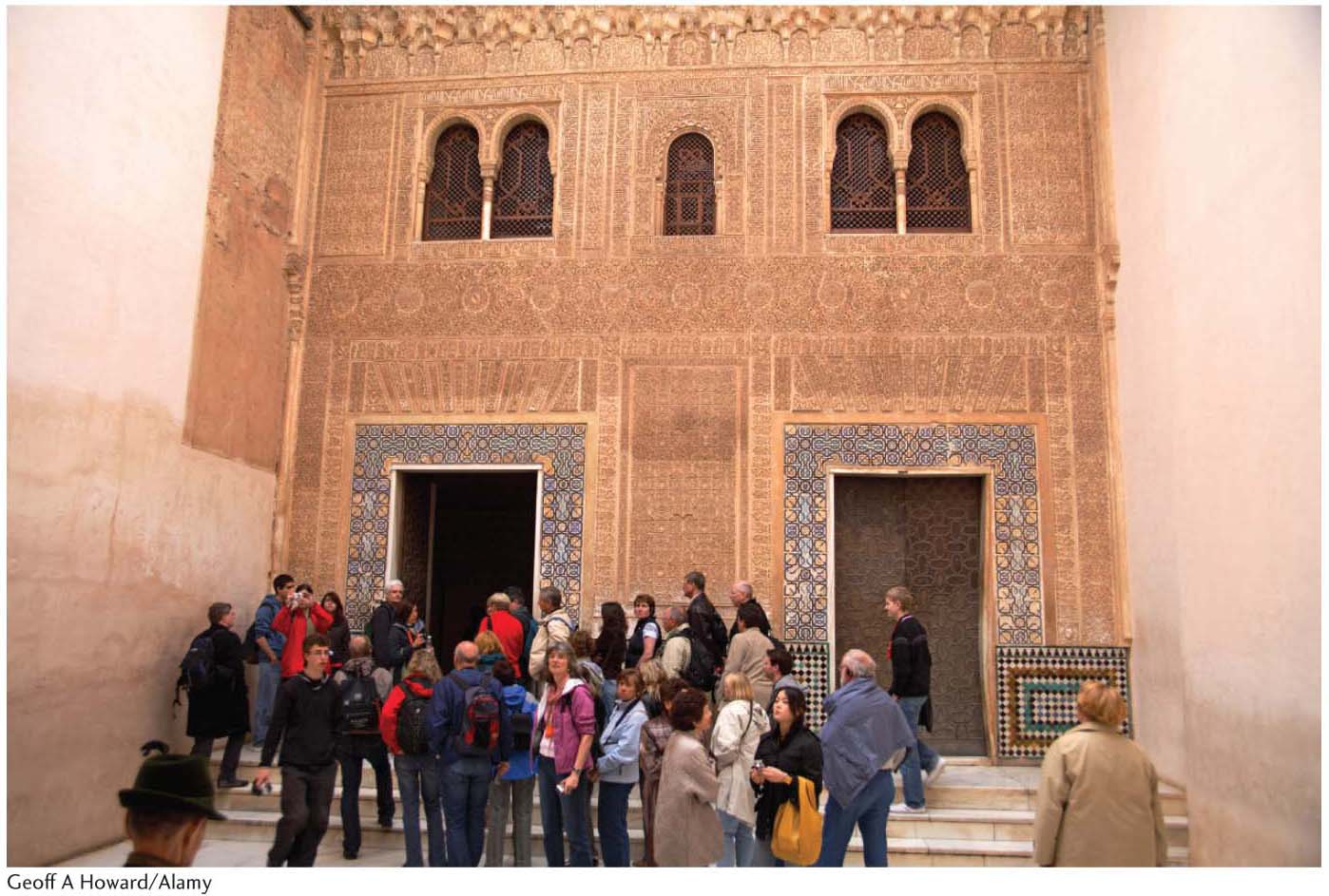

From the eleventh through fourteenth centuries, Muslim rulers, or emirs, oversaw the construction of the Alhambra fortress and residences, gardens of the Generalife, and the Albayzín residential quarter. From the eighth through fifteenth centuries, Spain was ruled by the Moors, Muslims of North African descent.

These sites are exceptional examples of Moorish imperial architecture. Though Spain became Christianized after the Moors were expelled in 1492, Spanish monarchs greatly admired and sought to safeguard the architectural achievements of the Moors in the Andalusian region of southern Spain. Through careful restoration, the architecture of these sites remains true to its Spanish-Moorish roots. The urban layout, colors, and materials look today much as they did over 700 years ago.

The Albayzín residential quarter occupies a hill that, according to archaeological evidence, has been continuously occupied since early Roman times (about 2500 years).

169

WALL WRITING IN THE ALHAMBRA: The original Alhambra fortress-palace was built by Samuel Ha-Nagid, an eleventh-century Jewish grand vizier (a prime minister of sorts) to the Zirid sultans of Granada. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the Nazrid emirs constructed an entire complex of palaces and irrigated gardens at the site. the buildings are adorned with what appear at first glance to be elaborate intricate designs. In reality, the walls, ceilings, and other architectural elements are covered with words. over 10,000 Arabic inscriptions adorn the interior of the Alhambra complex. “There is probably no other place in the world where studying walls, columns and fountains is so similar to turning the pages of a book” according to Spanish researcher Juan Castilla.

Islamic architecture is typically adorned with decorative writing called calligraphy and other geometric patterns, rather than representations of living beings. According to some Muslims, figural representation was a form of idolatry (the worship of a physical object as a God), while others saw the body as an imperfect covering for the soul.

Because calligraphy was commonly regarded as the preeminent expression of the visual arts, calligraphers typically had a higher status than other artists and were housed in the Ministry of Writing.

Efforts to digitally archive and transcribe the wall writing reveal that fewer than 10 percent of the inscriptions are Qur’anic (religious) verses or poetry. The rest offer praise to the Nasrid emirs or consist of other popular sayings, with “There is no victor but Allah” being the most common inscription.

TOURISM: This site attracts a huge number of international tourists, most of whom arrive in the summer months.

The number of tourists to the Alhambra is limited to a daily quota of 6600.

Unfortunately, the decorative surfaces of the site’s buildings are not well protected, so they continue to be worn away through the touch of so many tourists.

The picturesque city of Granada is situated on a series of hills against the backdrop of the Sierra Mountains. Tourists enjoy the mix of Mediterranean cultures, cuisines, and traditions there.

This World Heritage Site was built by and for the Moorish rulers of southern Spain, and exemplifies the pinnacle of Andalusian architecture, a synthesis of classical Arabic and southern Spanish styles.

The interior structures of the Alhambra palace are covered with more than 10,000 intricate inscriptions in Arabic calligraphy.

The Alhambra and the Generalife were placed on the list of World Heritage Sites in 1984, and in 1994 the site was expanded to include the Albayzín quarter.

http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/314

170

SEEING GEOGRAPHY

SEEING GEOGRAPHY

Aquí se habla Spanglish What does this sign tell you about who lives in this city?

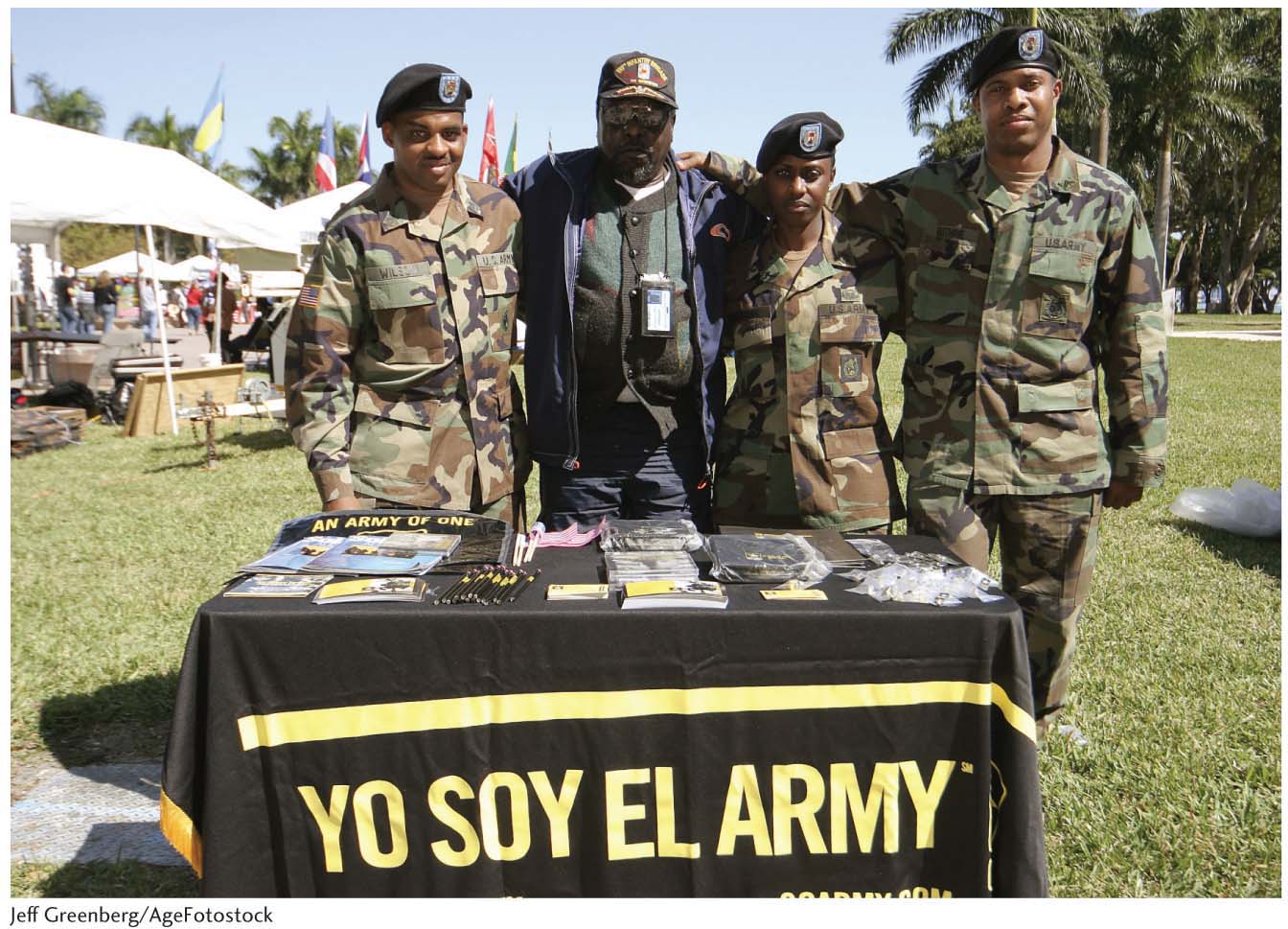

U.S. Army veterans at a recruiting table in Miami, Florida.

(Jeff Greenberg/AgeFotostock.)

Languages are fluid, always being altered and reinvented as the needs and experiences of their users change. Thanks to relocation diffusion resulting from the conquest of the East Coast of North America by the British in the seventeenth century, the primary language of the United States is English. The language then expanded westward as English-speaking peoples conquered more and more of the continent’s territory. But, the English spoken in Britain’s overseas colonies has never been “the Queen’s English.” Rather, British colonies in North America, Australia, the Caribbean, Africa, and eastern and southern Asia all developed their own distinctive dialects. Indigenous words have been incorporated into English vocabularies, as the sections on toponyms in this chapter show. Pidgins, creoles, and distinctive dialects have resulted in places of high multilingual exposure, such as Singapore and the Anglophone Caribbean islands. Waves of immigrants have added further to the linguistic richness of English-speaking areas.

In 2002, Hispanics surpassed African Americans as the nation’s numerically most significant minority group. In some U.S. cities, Hispanics constitute more than half of the population, a fact that brings into question the designation “minority.” For example, the population of Miami, Florida, is two-thirds Hispanic, and more than three-fourths of the residents of El Paso and San Antonio, Texas, are Hispanic. In the United States today, Spanish-speaking peoples from Latin America provide the largest flow of immigrants into the United States. Even midsize and smaller towns in the midwestern and southern United States are becoming destinations for Spanish-speaking immigrants, sharply changing the ethnic composition of cities such as Shelbyville, Tennessee; Dubuque, Iowa; and Siler City, North Carolina.

It is logical to assume that the Spanish language spoken by these new immigrants, and by the families of Hispanic Americans, will have a growing impact on American English. As the opening photograph for this chapter illustrates, Spanish words have become common sights in U.S. cities, appearing frequently on street signs. But, Spanish and English have combined in a rich, complex fashion as well, to produce a hybrid language called Spanglish. The phrase “Vámonos al downtown a tomar una bironga after work hoy” is an excellent example. It translates into Standard English as “Let’s go downtown and have a beer after work today.” Vámonos (“let’s go”), tomar (“to drink”), and hoy (“today”) are Spanish words that are combined in the same sentence with the English words downtown and after work. Linguists refer to this tendency to shift between languages in the same sentence, a very common practice among bilingual speakers, as code-switching. However, the noun bironga, which means “beer” in English, is a Spanglish invention: it exists in neither English nor Spanish. This is quite common in Spanglish, and neologisms such as hanguear (“to hang out”), deioff (“day off”), and parquear (“to park” a vehicle) abound.

171

In the image that opens this chapter, the phrase “Yo soy el Army” employs both Spanish and English to recruit. This image also underscores that people of Hispanic descent can be of any race.

Spanglish reflects the growing Spanish-English bilingualism of many U.S. residents, the flexibility of language, and the enduring creativity of human beings as we attempt to communicate with one another. Ilan Stavans, author of Spanglish: The Making of a New American Language, likens Spanglish to jazz. “Yes,” Stavans writes, “it is the tongue of the uneducated. Yes, it’s a hodgepodge. . . . But its creativity astonished me. In many ways, I see in it the beauties and achievements of jazz, a musical style that sprung up [sic] among African-Americans as a result of improvisation and lack of education. Eventually, though, it became a major force in America, a state of mind breaching out of the ghetto into the middle class and beyond. Will Spanglish follow a similar route?”