REGION

7.1

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Define the differences among religions as well as the basic tenets of the world’s principal religions, and locate their primary regional expressions on a world map.

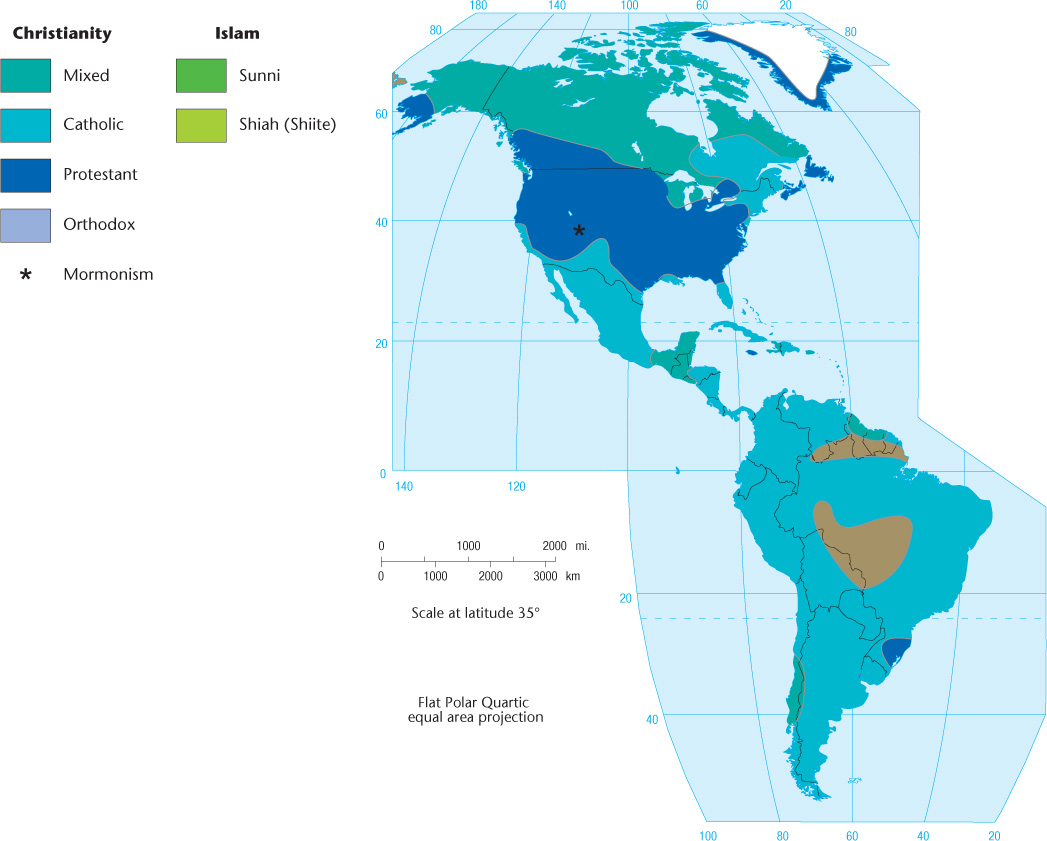

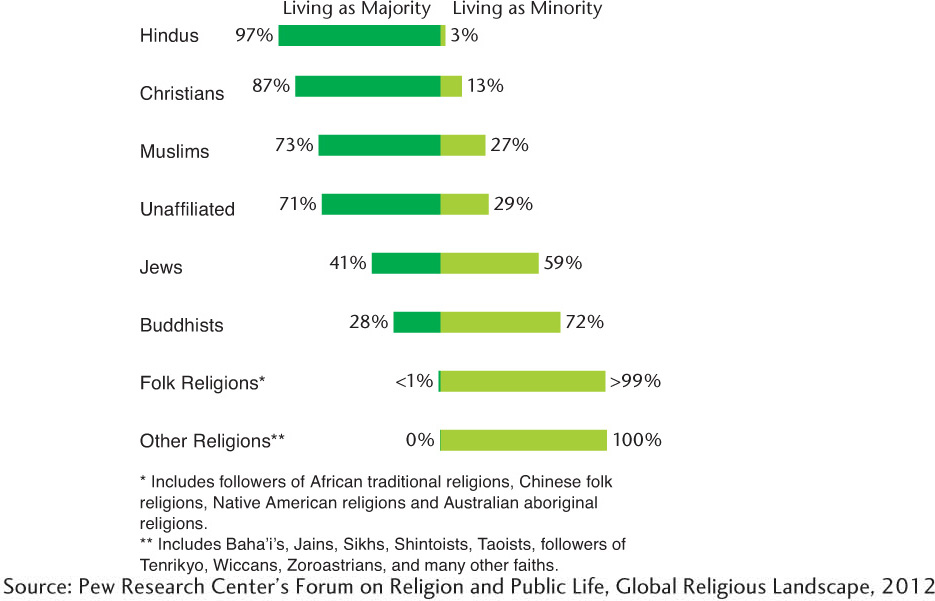

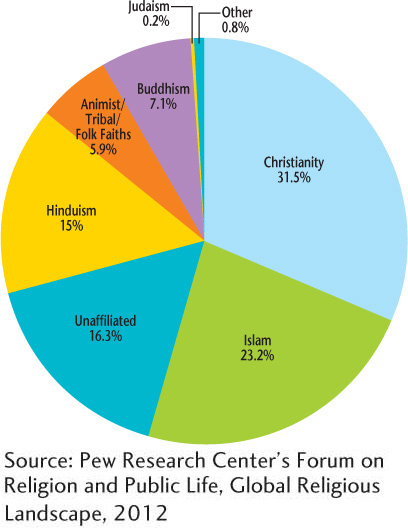

Because religion, like all of culture, has a strong territorial association, religious culture regions abound. The most basic kind of formal religious culture region depicts the spatial distribution of organized religions (Figure 7.3). Some religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism, are strongly associated with one world region, while others, such as Islam and Christianity, are dispersed across many regions (Figure 7.4). Some parts of the world exhibit an exceedingly complicated pattern of religious adherence, and the boundaries of formal religious culture regions, like most cultural borders, are rarely sharp. While roughly three-quarters of the world’s inhabitants live in countries where their religion is in the majority, persons of different faiths often live in the same province or town.

JUDAISM

Judaism is a 4000-year-old religion and the first major monotheistic faith to arise in southwestern Asia. It is the parent religion of Christianity and is also closely related to Islam. Jews believe in one God who created humankind for the purpose of bestowing kindness on them. As with Islam and Christianity, people are rewarded for their faith, are punished for violating God’s commandments, and can atone for their sins. The Jewish holy book, or Torah, comprises the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. In contrast to other monotheistic faiths, Judaism is not proselytic and has remained an ethnic religion through most of its existence.

Judaism has split into a variety of subgroups, partly as a result of the Diaspora, a term that refers to the forced dispersal of the Jews from Palestine in Roman times and the subsequent loss of contact among the various colonies. Jews, scattered to many parts of the Roman Empire, became a minority group wherever they went. In later times, they spread throughout much of Europe, North Africa, and Arabia. Those Jews who lived in Germany and France before migrating to central and eastern Europe are known as the Ashkenazim; those who never left the Middle East and North Africa are called Mizrachim; and those from Spain and Portugal are known as Sephardim. Spain expelled its Sephardic Jews in 1492, the same year that Christopher Columbus set sail for the New World. It was not until the quincentennial of both events, in 1992, that the Spanish government issued an official apology for the expulsion.

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed large-scale Ashkenazic migration from Europe to America. The Holocaust that befell European Judaism during the Nazi years involved the systematic murder of perhaps a third of the world’s Jewish population, mainly Ashkenazim. Europe ceased to be the primary homeland of Judaism, and many of the survivors fled overseas, mainly to the Americas and later to the newly created state of Israel. Today, Judaism has about 15 million adherents throughout the world. At present, a roughly equal number—6 million—of the world’s Jews reside in North America and Israel; Europe and Latin American are home to most of the rest.

CHRISTIANITY

Christianity, a proselytic faith, is the world’s largest religion, both in area covered and in number of adherents, claiming about a third of the global population (Figure 7.5). Christians are monotheistic, believing that God is a Trinity consisting of three persons: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Jesus Christ is believed to be the incarnate Son of God who was given to humankind for the sake of redemption some 2000 years ago. Through Jesus’s death and resurrection, all of humanity is offered redemption from sin and provided eternal life in heaven and a relationship with God.

Christianity, Islam, and Judaism are the world’s three great monotheisms and share a common culture hearth in southwestern Asia (see Figure 7.14). All three religions venerate the patriarch Abraham and thus are often called Abrahamic religions. Because Judaism is the parent religion of Christianity, the two faiths share many elements, including the Torah, the first five books of what Christians call the Old Testament (which forms part of the Christian Bible or holy book); prayer; and a clergy. This is the basis for the term Judeo-Christian, which is used to describe beliefs and practices shared by the two faiths. Because Jesus was born into the Jewish faith, many Christians still accord Jews a special status as a chosen people and see Christianity as the natural continuation or fulfillment of Judaism.

276

Christianity has long been fragmented into separate branches (see Figure 7.3). The major division is threefold, made up of Roman Catholics, Protestants, and Eastern Christians. Western Christianity, which now includes Catholics and Protestants, was initially identified with Rome and the Latin-speaking areas that are largely congruent with modern western Europe, whereas the Eastern Church dominated the Greek world from Constantinople (now the city of Istanbul, Turkey). Belonging to the Eastern group are the Armenian Church, reputedly the oldest in the Christian faith and today centered among a people of the Caucasus region; the Coptic Church, originally the religion of Christian Egyptians and still today a minority faith there, as well as being the dominant church among the highland people of Ethiopia; the Maronites, Semitic descendants of seventh-century heretics who disagreed with some of early Christianity’s beliefs and retreated to a mountain refuge in Lebanon; the Nestorians, who live in the mountains of the Middle East and in India’s Kerala state; and Eastern Orthodoxy, originally centered in Greek-speaking areas. Having converted many Slavic groups, Orthodox Christianity is today made up of a variety of national churches, such as Russian, Greek, Ukrainian, and Serbian Orthodoxy, with a collective membership of some 260 million (Figure 7.6).

277

278

Western Christianity splintered, most notably with the emergence of Protestantism in the Reformation of the l400s and l500s. As with all religious reformation movements, Protestantism sought to overcome what were viewed to be the wrong practices of Roman Catholicism, such as the need for priestly or saintly mediation between humans and God, while still staying within the general framework of Christianity. Since then, the Roman Catholic Church, which alone includes 1.1 billion people, or more than one-sixth of humanity, has remained unified; but Protestantism, from its beginnings, tended to divide into a rich array of sects, which together and including Anglican and independent Christians have a total membership today of about 801 million worldwide.

279

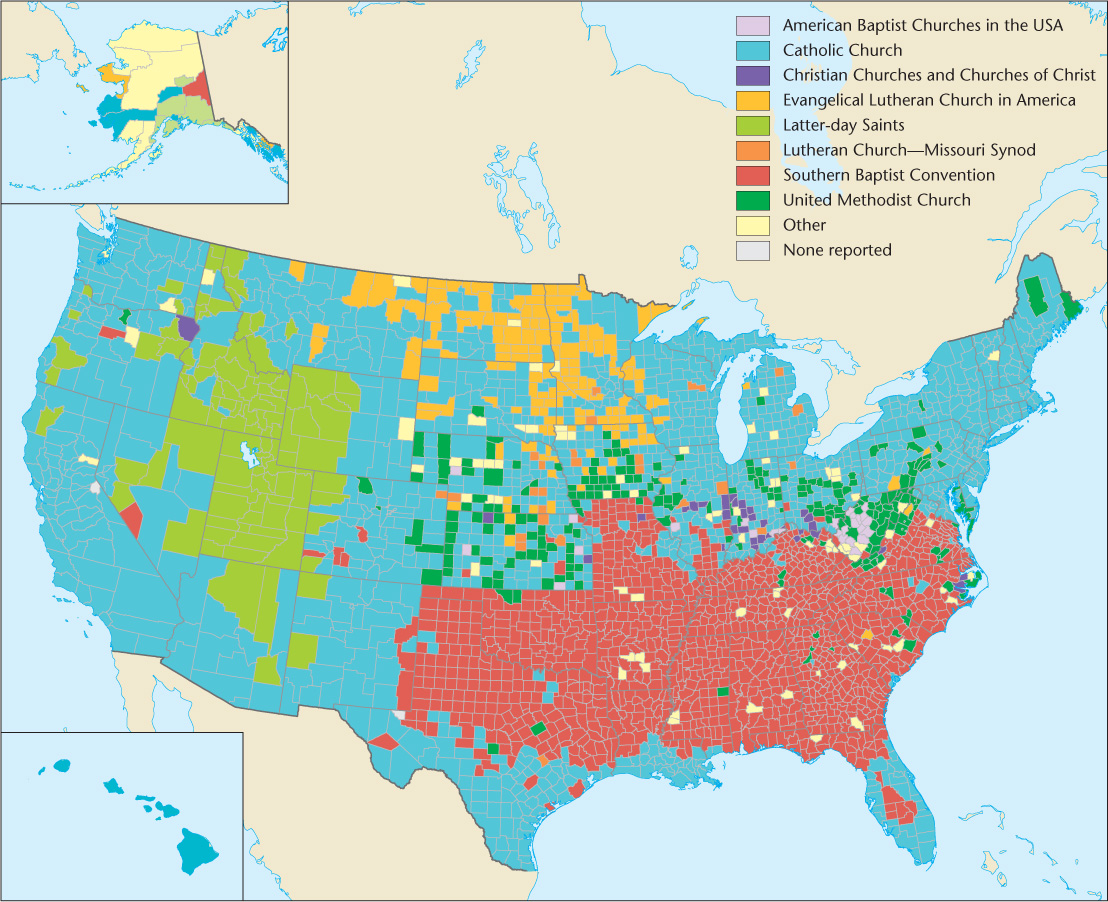

In the United States and Canada, the denominational map vividly reflects the fragmentation of Western Christianity and the resulting complex pattern of religious culture regions (Figure 7.7). Numerous denominations imported from Europe were later augmented by Christian denominations that originated in America. The American frontier was a breeding ground for new religious groups, as individualistic pioneer sentiment found expression in splinter Protestant denominations. Today, in many parts of the country, even a relatively small community may contain the churches of half a dozen religious groups. As a result, we can find about 2000 different religious denominations and cults in the United States alone. In a broad Bible Belt across the South, Baptist and other conservative fundamentalist denominations dominate, and Utah is at the core of the Mormon realm. A Lutheran belt stretches from Wisconsin westward through Minnesota and the Dakotas, and Roman Catholicism is dominant in southern Louisiana, the southwestern borderland, and heavily industrialized areas of the Northeast. The Midwest is a thoroughly mixed zone, although Methodism is the largest single denomination.

280

Today, Christianity is geographically widespread and highly diverse in its local interpretation. Although it is not as fast-growing as Islam, intense missionary efforts strive to increase the number of adherents.

Because of this proselytic work, Africa and Asia are the fastest-growing regions for Christianity.

Subject To Debate: RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM

Subject To Debate

RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM

Throughout history, religions have been one of the main ways in which people have attempted to make sense of the changing world around them. Although we may associate globalization with the fast pace and seemingly shrinking world of the past half century or so, people from diverse cultures have, in fact, been in contact across the globe for thousands of years. So how have religions helped people to cope with the changes brought about by new ideas, new ways of doing things, and new belief systems?

One response is acceptance. The Muslim conquest of Iberia in the eighth century brought a centuries-long flourishing of culture to modern-day Spain and Portugal. Islamic rule here was noted for its humane and enlightened nature, whereas the rest of western Europe languished in the Dark Ages. The Muslims who ruled Iberia were renowned for their religious tolerance, and they included Jews and Christians as valued members of their governmental, scientific, and artistic communities.

Another response is intolerance. When Buddhism branched off from Hinduism, its parent religion, not all Hindus were pleased at the way Buddhism replaced Hinduism in some areas. Angkor Wat (see Figure 11.24), a temple complex in Cambodia, is replete with bas-relief carvings of Buddha figures with their faces either entirely chipped off or recarved to resemble Hindu deities. Hindus intolerant of the Khmer King Jayavarman VII’s Buddhist beliefs were responsible for defacing these sacred images on the king’s death in 1220 C.E.

Yet another response is syncretism, where elements of preexisting faiths are blended with new ones in order to make them more palatable. An example is the scheduling of the Christmas holidays during the older Roman holiday period celebrating the Roman deity Saturn. This occurred in the third and fourth centuries C.E., as Rome was beginning to Christianize, as a way to encourage Romans to adopt Christianity. Feasting, gift giving, singing in the streets (caroling), and consuming human-shaped cookies (gingerbread men) are some of the traditions from the Saturnalia festivities that have found their way into Christmas celebrations.

Today many religions, including Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, and Islam, are experiencing intense fundamentalist movements. Fundamentalism means a return to the founding principles of a religion, which may include a literal interpretation of sacred texts and an attempt to follow the ways of a religious founder as closely as possible. Fundamentalists draw a sharp distinction between themselves and other practitioners of their religion, whom they do not believe to be following the proper religious principles, and between themselves and adherents of other faiths. Fundamentalism can be seen as an attempt to purify religious belief and practice in the face of modern influences thought to debase the religion. These tendencies have led to fundamentalists being regarded as antimodern and intolerant, although this view is strongly disputed by fundamentalists themselves.

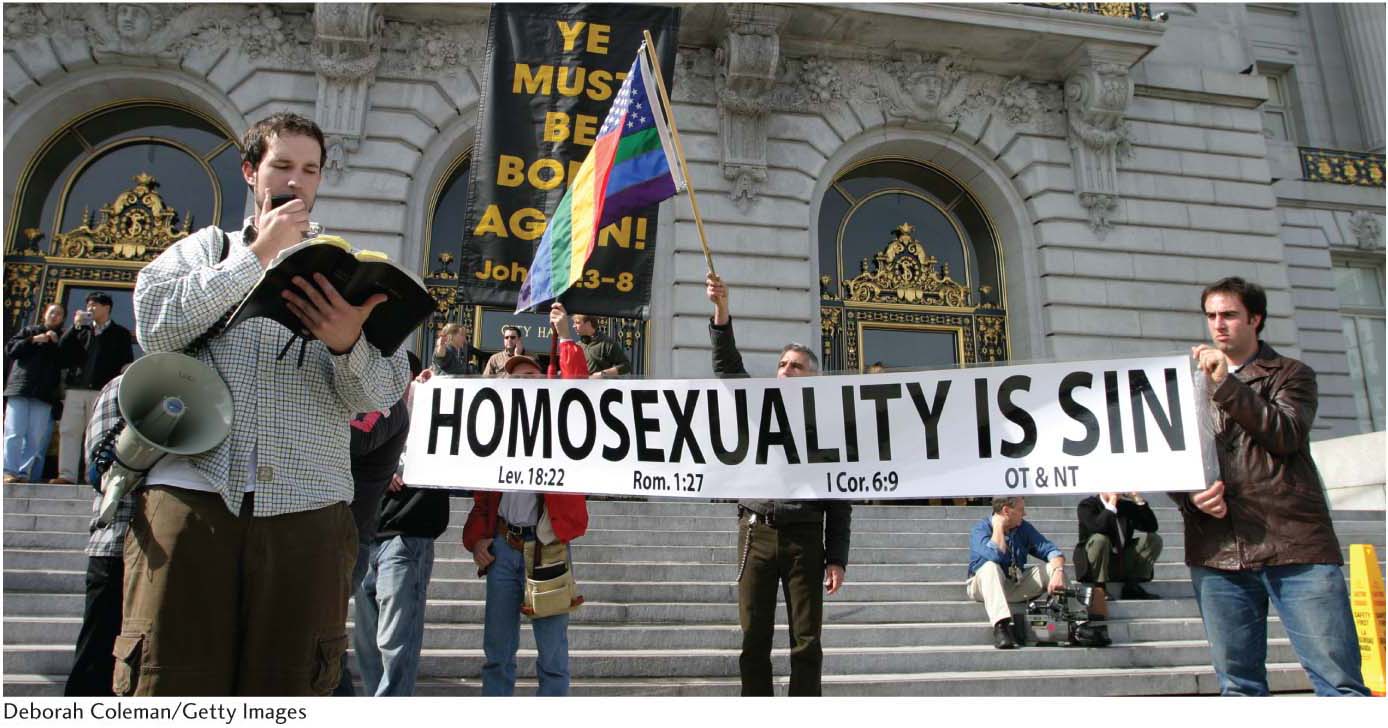

Fundamentalism is an emotionally charged term because it is often used to portray its followers derogatorily as radical extremists. The tendency of the U.S. media to use the term Islamic fundamentalists as a synonym for terrorists is an unfortunate example of this. Yet there are connections between politics and religious fundamentalism. The political agenda of the U.S. government on matters of abortion, adoption, marriage, foreign policy, domestic security, gay rights, and the curriculum in public schools has been notably influenced by politically conservative religious groups. Although not all of these groups are entirely fundamentalist in nature, many embrace fundamentalist Christian beliefs that espouse creationism and the sinfulness of homosexuality as well as question the separation of church and state. Islamism, a political ideology based in conservative Muslim fundamentalism, holds that Islam provides the political basis for running the state. Similar to the influence of Christian fundamentalism, Islamist influences in several Muslim-majority countries have set a conservative social agenda and have strongly questioned the separation of church and state.

281

Continuing the Debate

We often hear about religion in connection with violence. The next time you watch a news video or read a newspaper, keep these questions in mind:

Do all religions have a dark, violent side to them, even those that profess a peaceful worldview?

Is violence a necessary corollary to religious fundamentalism?

What role does the media play in creating the perception—or inciting the practice—of religious antagonism?

ISLAM

Islam, another great proselytic faith, claims 1.6 billion followers, largely in the desert belt of Asia and northern Africa and in the humid tropics as far east as Indonesia and the southern Philippines (see Figure 7.3 and Figure 7.5). Adherents of Islam, known as Muslims (literally, “those who submit to the will of God”), are monotheists and worship one absolute God known as Allah. Islam was founded by Muhammad, considered to be the last and most important in a long line of prophets. The word of Allah is believed to have been revealed to Muhammad by the angel Gabriel (Jibrail) beginning in 610 C.E. of the Christian calendar in the Arabian city of Mecca (Figure 7.8). The Qur’an, Islam’s holy book, is the text of these revelations and also serves as the basis of Islamic law, or Sharia. Most Muslims consider both Jews and Christians to be, like themselves, “people of the Book,” and all three religions share beliefs in heaven, hell, and the resurrection of the dead. Many biblical figures familiar to Jews and Christians, such as Moses, Abraham, Mary, and Jesus, are also venerated as prophets in Islam. Adherents to Islam are expected to profess belief in Allah, the one God whose prophet was Muhammad; pray five times daily at established times; give alms, or zakat, to the poor; fast from dawn to sunset during the holy month of Ramadan; and make at least one pilgrimage, if possible, to the sacred city of Mecca in Saudi Arabia. These duties are known as the Five Pillars of the faith.

282

Although not as severely fragmented as Christianity, Islam, too, has split into separate groups. Two major divisions prevail. Shiite Muslims, 16 percent of the Islamic total in diverse subgroups, form the majority in Iran and Iraq. Shiites believe that Ali, who was Muhammad’s son-in-law, should have succeeded Muhammad. Sunni Muslims, who represent the Islamic orthodoxy (the word Sunni comes from sunnah, meaning “tradition”), form the large majority worldwide (see Figure 7.3). Islam has not undergone a reformation parallel to that undergone by Christianity with Protestantism. However, reformation is the goal of liberal movements within Sunni and Shiite Islam.

Islam’s strength is greatest in the Arabic-speaking lands in Southwest Asia and North Africa, although the world’s largest Islamic population is found in Indonesia. Other large clusters live in Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and western China. Because of successful conversion efforts in non-Muslim areas and high birthrates in predominantly Muslim areas, Islam is the fastest-growing world religion. In the United States, more people convert to Islam than to any other religion, and Islam will soon surpass Judaism to become America’s second-largest faith.

HINDUISM

Hinduism, a religion closely tied to India and its ancient culture, claims about 1 billion adherents (see Figure 7.3 and Figure 7.5). Hinduism is a decidedly polytheistic religion. Although Hindus recognize one supreme god, Brahman, it is his many manifestations that are worshipped directly. Some principal Hindu deities include Vishnu, Shiva, and the mother goddess Devi. Ganesha, the elephant-headed god depicted in Figure 7.9, is often revered by Hindu university students because Ganesha is the god of wisdom, intelligence, and education. Believing that no one faith has a monopoly on the truth, most Hindus are notably tolerant of other religions (but see Subject to Debate).

Hindus strive to locate the harmonious and eternal truth, dharma, which is within each human being. Social divisions, or castes, separate Hindu society into four major categories, or varna, based on occupational categories: priests (Brahmins), warriors (Kshatriyas), merchants and artisans (Vaishyas), and workers (Shudras). Castes are related to dharma inasmuch as dharma implies a set of rules for each varna that regulate their behaviors with regard to eating, marriage, and use of space. All Hindus also share a belief in reincarnation, the idea that, although the physical body may die, the soul lives on and is reborn in another body. Related to this is the notion of karma. Karma can be viewed almost as a causal law, which holds that what an individual experiences in this life is a direct result of that individual’s thoughts and deeds in a past life. Likewise, all thoughts and deeds, both good and bad, affect an individual’s future lives. Ultimately, moksha, or liberation of the soul from the cycle of death and rebirth, will occur when the worldly bonds of the material self fall away and one’s pure essence is freed. Ahimsa, or the principle of nonviolence, involves veneration of all forms of life. This implies a principle of noninjury to all sentient creatures, which is why many Hindus are vegetarians.

283

Hinduism has splintered into diverse groups, some of which are so distinctive as to be regarded as separate religions. Jainism, for instance, is an ancient outgrowth of Hinduism, claiming perhaps 4 million adherents, almost all of whom live in India, and traces its roots back more than 25 centuries. Although they reject Hindu scriptures, rituals, and priesthood, the Jains share the Hindu belief in ahimsa and reincarnation. Jains adhere to a strict asceticism, a practice involving self-denial and austerity. For example, they practice veganism, a form of vegetarianism that prohibits the consumption of all animal-based products, including milk and eggs. Sikhism, by contrast, arose much later, in the 1500s, in an attempt to unify Hinduism and Islam. Centered in the Punjab state of northwestern India, where the Golden Temple at Amritsar serves as the principal shrine, Sikhism has about 23 million followers. Sikhs are monotheistic and have their own holy book, the Adi Granth.

No standard set of beliefs prevails in Hinduism, and the faith takes many local forms. Hinduism includes very diverse peoples. This is partly a result of its former status as a proselytic religion. A Hindu majority on the Indonesian island of Bali suggests the religion’s former missionary activity (Figure 7.10). Today, most Hindus consider their religion an ethnic one, whereby one is acculturated into the Hindu community by birth; however, conversion to Hinduism is also allowed. Hindus form a majority in only three countries: Nepal, India, and Mauritius. Yet 97 percent of the world’s Hindus live in these three countries; thus, Hindus are more likely than any other faith to constitute a majority in the country where they reside (see Figure 7.4).

284

BUDDHISM

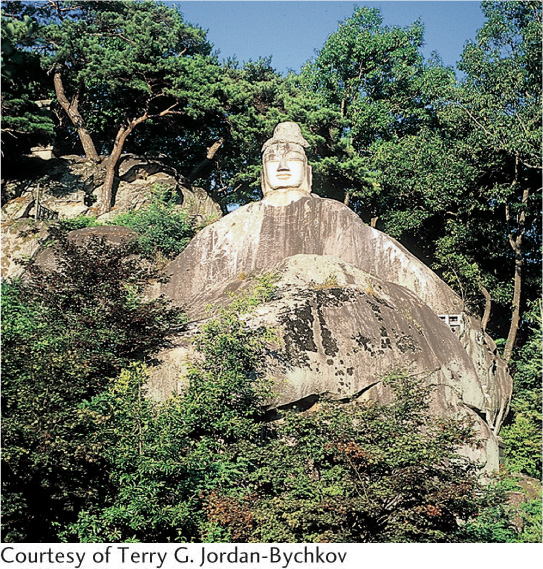

Hinduism is the parent religion of Buddhism, which began 25 centuries ago as a reform movement based on the teachings of Prince Siddhartha Gautama, “the awakened one” (Figure 7.11). He promoted the four “noble truths”: life is full of suffering, desire is the cause of this suffering, cessation of suffering comes with the quelling of desire, and an Eightfold Path of proper personal conduct and meditation permits the individual to overcome desire. The resultant state of enlightenment is known as nirvana. Those few individuals who achieve nirvana are known as Buddhas. The status of Buddha is open to anyone regardless of social status, gender, or age. Because Buddhism derives from Hinduism, the two religions share many beliefs, such as dharma, reincarnation, and ahimsa. Buddhism and its parent religion, Hinduism, as well as the related faiths Jainism and Sikhism, are known as dharmic religions.

Today, Buddhism is the most widespread religion in South and East Asia, dominating a culture region stretching from Sri Lanka to Japan and from Mongolia to Vietnam. In the process of its proselytic spread, particularly in China and Japan, Buddhism fused with native ethnic religions such as Confucianism, Taoism, and Shintoism to form syncretic faiths that fall into the Mahayana division of Buddhism. Southern, or Theravada, Buddhism, dominant in Sri Lanka and mainland Southeast Asia, retains the greatest similarity to the religion’s original form, whereas a variation known as Tantrayana, or Lamaism, prevails in Tibet and Mongolia (see Figure 7.3). Buddhism’s tendency to merge with native religions, particularly in China, makes it difficult to determine the number of its adherents. Estimates range from 350 million to more than 500 million people (see Figure 7.5). Although Buddhism in China has become mingled with local faiths to become part of a composite ethnic religion, elsewhere it remains one of the three great proselytic religions in the world, along with Christianity and Islam.

TAOIC RELIGIONS

Confucianism, Shinto, and Taoism together make up the faiths that center on Tao, or the force that balances and orders the universe. Derived from the teachings of philosopher K’ung Fu-tzu (551-479 B.C.E.), Confucianism was later promoted by China’s Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.-220 C.E.) as the official state philosophy. Thus, it has bureaucratic, ethical, and hierarchical overtones that have led some to question whether it is more a way of life than a religion in the proper sense. In China, Confucianism’s formalism is balanced by Taoism’s romanticism. Taoism, which is both an established religion and a philosophy, emphasizes the dynamic balance depicted by the Chinese yin-yang symbol. The “three jewels of Tao” are humility, compassion, and moderation. Shinto, once the state religion of Japan, has long been blended with Buddhism, as well as infused with a Confucian-derived legal system, but at its core Shinto is an animistic religion. Because Tao is found in nature, there is some overlap with the animistic faiths discussed next. In addition, because of their fluid nature, Taoic religions tend toward syncretism and have blended with other faiths, particularly Buddhism. People may simultaneously practice elements of all these faiths. For these reasons, it is difficult to provide an exact number of adherents, although estimates hold that there are about half a billion. Taoic religions center on East Asia (see Figure 7.3).

285

ANIMISM/SHAMANISM

Peoples in diverse parts of the world often retain indigenous religions and are usually referred to collectively as animists (Figure 7.12). For the most part, animists do not form organized or recognized religious groups but instead practice as ethnic religions common to clans or tribes. In addition, most animists follow oral, rather than written, traditions and thus do not have holy books. A tribal religious figure, called by some a shaman, usually serves as an intermediary between the people and the spirits.

Currently numbering perhaps 240 million, animists believe that nonhuman beings and inanimate objects possess spirits or souls. These spirits are believed to live in rocks and rivers, on mountain peaks and celestial bodies, in forests and swamps, and even in everyday objects. As such, objects are considered to be alive, and depending on the local beliefs, objects and animals may assume human forms or engage in human activities such as speech. For some animists, the objects in question do not actually possess spirits but rather are valued because they have a particular potency to serve as a link between a person and the omnipresent god. Followers of Wicca, a contemporary neopagan religion derived from pre-Christian European practices of reverence for the mother goddess and the horned god, worship the god and goddess who are thought to inhabit everything. Ritual tools used by Wiccans include the athame (dagger), boline (knife), and besom (broom), which are used in ceremonies to direct energy as practitioners communicate with the god and goddess.

animists

Adherents of animism, the idea that souls or spirits exist in not only humans but also animals, plants, rocks, natural phenomena such as thunder, geographic features such as mountains or rivers, or other entities of the natural environment.

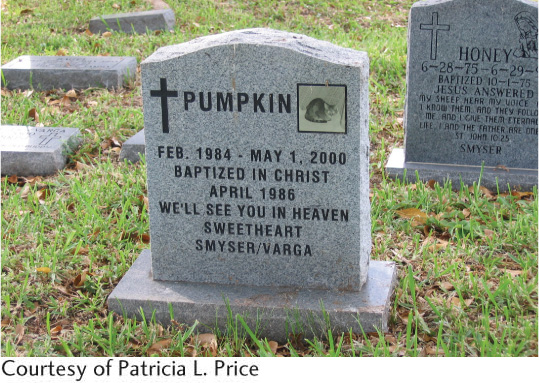

Animistic elements can also pervade established religions. Japanese Shinto adherents worship kami, or spirits, that inhabit natural objects such as waterfalls and mountains. We should not classify such systems of belief as primitive or simple because they can be extraordinarily complex. Even in places such as the United States, where the majority of the inhabitants would not see themselves as animists, such beliefs are pervasive. For example, many people in the United States believe that their pets possess souls that ascend to heaven on death (Figure 7.13).

286