461

CHAPTER [strong]15[/strong]

The Milky Way Galaxy

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

What is the shape of the Milky Way Galaxy?

What is the shape of the Milky Way Galaxy?

Where is our solar system located in the Milky Way Galaxy?

Where is our solar system located in the Milky Way Galaxy?

Is the Sun moving through the Milky Way Galaxy and, if so, about how fast?

Is the Sun moving through the Milky Way Galaxy and, if so, about how fast?

Answers to these questions appear in the text beside the corresponding numbers in the margins and at the end of the chapter.

462

By the beginning of the twentieth century, astronomers knew that we live in a forest of stars and interstellar matter called the Milky Way Galaxy. Just as nearby trees and their leaves hide what lies behind them, the stars and interstellar clouds we can see block light from more distant objects. A discussion ensued back then as to whether there is only one forest, culminating in the inconclusive Shapley–Curtis debate on whether or not the Milky Way fills all space and therefore contains all the “trees” (that is, the stars, other matter, and radiation) that exist. Observations presented in 1924 finally enabled astronomers to see clearly that there are myriad forests, separated from ours by vast regions of relatively empty space. Observations have since revealed that the other forests, also called galaxies, number in the billions. By the end of the twentieth century, astronomers knew that the galaxies that fill the universe are clustered together, rather than randomly dotting the cosmic landscape. They had also discovered that these clusters of galaxies are themselves gathered together in “superclusters.”

The more stars, nebulae, galaxies, and other features that astronomers observed in the cosmos, the more evident it became that something else dwelled in each galaxy that they could not see. Wraithlike, this “dark matter” was necessary because the observable matter in each galaxy lacks sufficient gravitational force to keep the stars and other matter in that galaxy bound together. The dark matter must provide the rest of that gravitational binding force. Without it, the stars, gas, and dust in each galaxy would disperse. As the twenty-first century dawned, astronomers started getting glimpses of these wraiths, revealing that there are several kinds of them. Nevertheless, other than that it interacts gravitationally with matter that we can observe, we still do not know the nature of most of this dark matter.

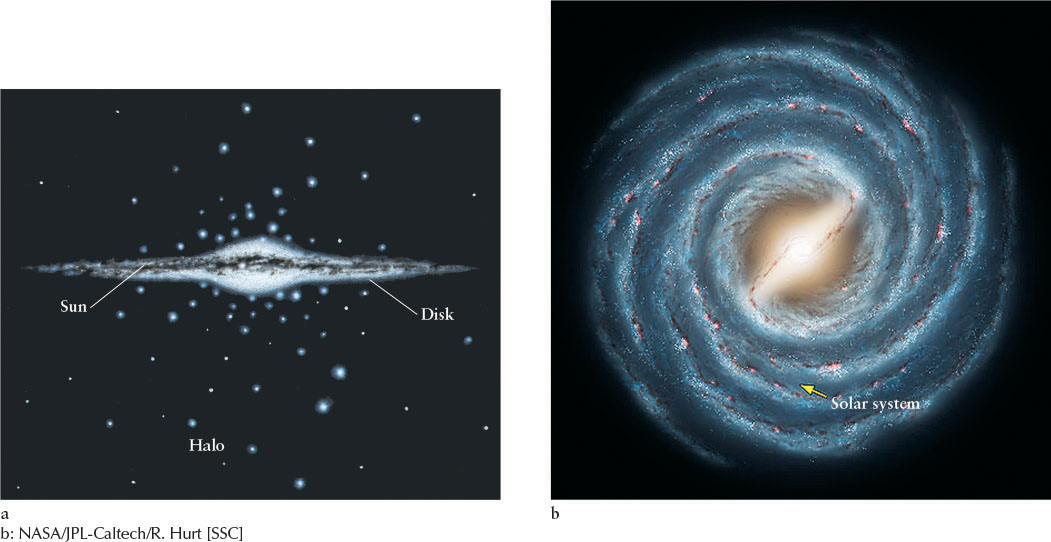

In this part of the book, we explore the galaxies, clusters of galaxies, superclusters of galaxies, the nature of the space that connects them, and the formation, evolution, and fate of the universe, which is defined to be all the matter, energy, and space that we can see or that can ever influence us. We begin by studying our Milky Way. For those fortunate enough to live away from bright outdoor lights and air pollution, the Milky Way appears as a veiled band overlaid with the glow of individual stars (see Figure 1-1). Centuries of observations have firmly established that the Milky Way is an enormous assemblage of hundreds of billions of stars, along with gas, dust, and other matter, all held together by their mutual gravitational attraction. Most of the stars in our Galaxy are located in a disk that looks from its edge like a flying saucer in an old science fiction movie (Figure 15-1a). The inner part of the disk is filled with stars, some of which form a bar (Figure 15-1b). Spiral arms swirl out from the ends of the bar, and, within these arms, new stars form from the debris of earlier generations of stars. The Galaxy’s remaining stars are located in a two-shell, spherical halo that surrounds the disk. (Note: The word “Galaxy” when used alone, as here, is capitalized only when it refers to our Milky Way.)

In the following two chapters, we will examine the rest of the galaxies and the supermassive black holes that lie at the hearts of most of them. Then, like biologists who study the origins and evolution of life, we consider what astronomers know about the formation, evolution, and fate of the universe. The book ends with a discussion of astrobiology—the interrelationship between life and astronomy.

463

In this chapter you will discover

the Milky Way Galaxy—billions of stars along with stellar remnants, gas, dust, and dark (meaning we do not yet know what it is) matter are all bound together by their mutual gravitational attraction

the Milky Way Galaxy—billions of stars along with stellar remnants, gas, dust, and dark (meaning we do not yet know what it is) matter are all bound together by their mutual gravitational attraction

the structure of our Milky Way Galaxy

the structure of our Milky Way Galaxy

Earth’s location in the Milky Way

Earth’s location in the Milky Way

how interstellar gas and dust enable star formation to continue

how interstellar gas and dust enable star formation to continue

that observations reveal the presence of significant mass in the Milky Way that astronomers have yet to identify

that observations reveal the presence of significant mass in the Milky Way that astronomers have yet to identify

that there is a supermassive black hole at the center of our Galaxy

that there is a supermassive black hole at the center of our Galaxy