Critical analysis, Shuqiao Song

“Residents of a DysFUNctional HOME” is a researched argument in which Shuqiao Song analyzes Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. You can use the markup tools to highlight and annotate this essay. Try these activities:

- Highlight the in-text references and compare them with citations at the end of the critical analysis to see how the two are connected in MLA style.

- To try a low-stakes practice peer review session, annotate with questions you would ask the writer. Show your annotations to your instructor for feedback or compare notes with classmates.

Watch the presentation based on this analysis

Activity: Analyze Shuqiao Song’s genre choices

Go to “Analysis activities” in the table of contents to try an activity using this student’s work.

Song 1

Shuqiao Song

Dr. Andrea Lunsford

English 87N

13 Mar. 2009

Residents of a DysFUNctional HOME

In a recent online interview, comic artist Alison Bechdel remarked, “I love words, and I love pictures. But especially, I love them together—in a mystical way that I can’t even explain” (Interview). Indeed, in her graphic novel memoir, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, text and image work together in a mystical way: text and image. But that little conjunction “and” is a deceitfully simple demonstration of the relationship between the two. Using both image and text results not in a simple summation but in a strange relationship—as strange as the relationship between Alison Bechdel and her father. These strange pairings have an alluring quality that makes Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home compelling; for her, both text and image are necessary. As Bechdel tells and shows us, alone, words can fail; alone, images deceive. Yet her life story ties both concepts inextricably to her memories and revelations such that only the interplay of text and image offers the reader the rich complexity, honesty, and possibilities in Bechdel’s quest to understand and find closure for the past.

The idea that words are insufficient is not new—certainly we have all felt moments when language simply fails us and we are at a loss of words—moments like being “left … wordless” by “the infinite gradations of color in a fine sunset” (Bechdel Fun 150). In those wordless moments, we strain to express just what we mean. Writers are especially aware of what is lost between word and meaning; Bechdel’s comment on the translation of Proust’s À la Recherche du Temps Perdu is a telling example of the troubling gap:

After Dad died, an updated translation of Proust came out. Remembrance of Things Past was re-titled In Search of Lost Time. The new title is a more literal translation of À la Recherche du Temps Perdu, but it still doesn’t quite capture the full resonance of perdu. This means not just lost, but ruined, undone, wasted, wrecked, and spoiled. (Bechdel Fun 119)

Song 2

Bechdel says of the new Proust title, “What’s lost in translation is the complexity of loss itself”—the very struggles of loss that Bechdel must also confront (Bechdel Fun 120). But how do we express something as complex as loss, if something is always lost between what we say and what we mean? Bechdel addresses the “complexity of loss” by trying to correlate herself with her father, attempting a “translation” of their lives (Bechdel Fun 120).

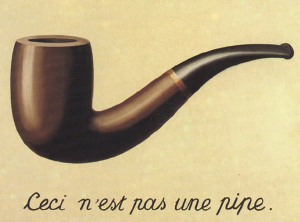

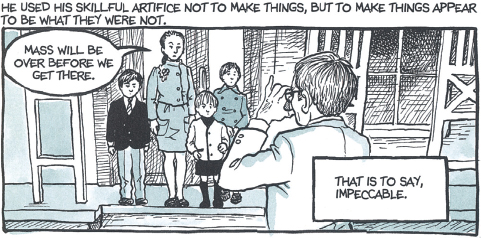

René Magritte’s painting The Treachery of Images (Fig. 1), with text that translates as “This is not a pipe,” reminds us to remain skeptical of images because images can deceive. This is a lesson that Alison Bechdel shows us again and again within her own story and images. Bechdel’s father constructs a false image of himself and of his home and family. The elaborately restored house is the gilded, but tense, context of young Alison’s familial relationships and a metaphor for her father’s deceptions. “He used his skillful artifice not to make things, but to make things appear to be what they were not,” Bechdel notes alongside an image of her father taking a photo of their family, shown in Fig. 2 (Bechdel Fun 16). The scene represents the nature of her father’s artifice; her father is posing a photo, an image of their family.

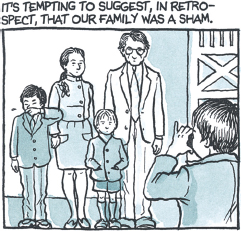

In that same scene, Bechdel also shows her own sleight of hand; she manipulates the scene to the purpose of her memoir and reverses her father’s role and her own to show young Alison taking the photograph of the family and her father posing in Alison’s place (Fig. 3). In the image, young Alison symbolizes Bechdel in the present—looking back through the camera lens to create a portrait of her family. But unlike her father, she isn’t using false images to deceive.

Song 3

Bechdel overcomes the treason of images by confessing herself as an “artificer” to her audience (Bechdel Fun 16). For example, in her grandmother’s story about her father being stuck in the mud as a baby, Bechdel admits to depicting her father being rescued by a milkman (instead of a mailman) because of the romantic notion that the milkman, dressed all in white, was “a reverse grim reaper” (Bechdel Fun 41). Bechdel doesn’t villainize the illusory nature of images; she repurposes their illusory power to reinterpret her memories. The nature of images allows her to illustrate the same scenes from different angles, but the angling and the new rendering of the scene hold new symbolic significance. Thus, despite the deceptive nature of images, they are still necessary to tell Bechdel’s story.

Song 4

Readers must understand that in Bechdel’s Fun Home, neither image nor text plays a supporting role. The text does not only caption the image and the image does not always literally illustrate the text. Each is a version of the memoir. Both are interpretations and manipulations. In Chapter 1, “Old Father, Old Artificer,” Bechdel draws up a tableau of her family situation. Here is an excerpt with only the text narration:

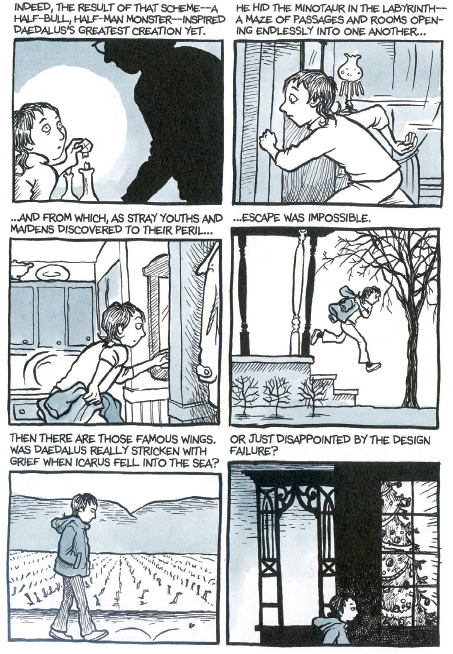

Daedalus, too, was indifferent to the human cost of his projects. He blithely betrayed the king, for example, when the queen asked him to build her a cow disguise so she could seduce the white bull. Indeed the result of that scheme—a half-bull, half-man monster—inspired Daedalus’s greatest creation yet. He hid the minotaur in the labyrinth—a maze of passages and rooms opening endlessly into one another … and from which, as stray youths and maidens discovered to their peril … escape was impossible. Then there are those famous wings. Was Daedalus really stricken with grief when Icarus fell into the sea? Or just disappointed by the design failure? (Bechdel Fun 11-12)

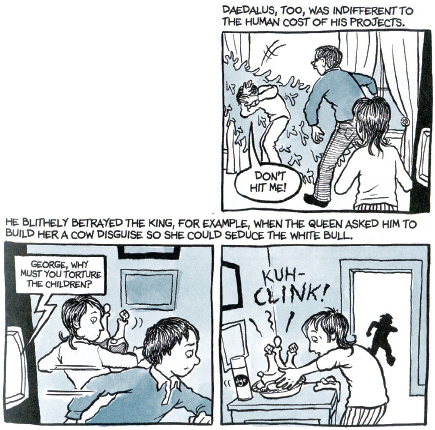

The text can stand alone as a story. However, a parallel storyline is lost. Karim Chabani notes, “To read a graphic novel is to follow a double narrative line, one pictorial and the other textual. On closer inspection, in Fun Home this ‘double line’ turns out to be two independent lines that are juxtaposed, playing at times side by side and on several occasions against one another. … [T]ext and images actually converge up to a point where they collide” (2).

Alone, the images tell a story distinct from the text (Fig. 4). Yet the ties between image and text are not severed. In the panel labeled “Daedalus, too, was indifferent to the human cost of his projects,” Bechdel correlates her father with Daedalus. Her father’s household “projects” are accomplished at the “human cost” of cruelty to his children, as the father strikes Alison’s brother and causes him to flee (Bechdel Fun 11). In the panel labeled “Indeed, the result of that scheme … inspired Daedalus’s greatest creation yet,” the reader shifts between the metaphors with surprising ease; now, her father is the looming minotaur whose wrath Alison fears (Bechdel Fun 12).

Song 5

The image evokes both the minotaur metaphor and young Alison’s genuine fear of her father’s anger. In the next three panels, she, too, runs out of the labyrinthine house. However, the text does not mesh exactly with what is seen within the frame: “… Escape was impossible,” Bechdel notes, but shows an image of young Alison fleeing the house and evading the wrath of her father (12). Bechdel uses the Daedalus story—and Daedalus’s relationship with Icarus—to explain her relationship with her father, but she complicates their relationship by casting both father and daughter as both Daedalus and Icarus. In the last two panels of this section, for example, her now-dead father is implied to be the fallen Icarus while Alison becomes the bereaved, disappointed artificer Daedalus. At last, the strange relationship between image and text emerges; image and text support each other, but the combined effect also reveals the many complex interconnections between the two. Young Alison’s escape effort holds a certain dramatic irony; she cannot escape the gravity of her father’s presence or the pages of the book—we see her drawn back to the house in the last frame of the Daedalus section (Bechdel Fun 12).

Song 6

Finally, we can see how image and text function together. On one hand, image and text support each other in that they each highlight the subtleties of the other. But, on the other hand, the more curious interaction comes when there is some degree of distance between what is written and what is depicted. In Fun Home, Bechdel pushes the boundaries of mental closure between image and text.

Song 7

If the words and pictures matched exactly, the story would read like a children’s book. However, text and image can’t be so mismatched that meaning is completely incomprehensible. Bechdel crafts her story deliberately, leaving space for the reader to experience cognitive dissonance. The reader’s need to create coherence from disparate text and image results in a more complex understanding of the story.

Through the strange but compelling pairings of image and text, the reader acquires a more thorough understanding of the strange and compelling relationship between father and daughter—what Jared Gardner calls “the story of the truth, and the truth of the story” (3). Bechdel consistently informs the reader that Fun Home is her interpretation of the past. She understands that “[t]he memoir is in many ways a huge violation of [her] family” (Chute 1009). As an artist, her effort to lay to rest her anxieties about her past comes at the cost of publicizing their family’s secrets in Fun Home. She does not let herself or the reader forget: “We really were a family, and we really did live in those period rooms” (Bechdel Fun 17). And perhaps this is why she dedicates Fun Home to “Mom, Christian, and John” (Bechdel Fun n.p.). Bechdel does not ignore the impact her act of remembering has on the present. In the end, her memoir is not about having an accurate record of events, but rather the incredible human ability for an emotional reappraisal of the past. Her stories told between the lines entwined with stories told within the frames impel our heads and hearts. And if nothing else, the painful confessions and wishful remembering of Fun Home provide a proper tribute for her father and allow Alison Bechdel a sense, almost, of closure.

Song 8

Works Cited

Bechdel, Alison. Fun Home. Houghton Mifflin, 2006. Print.

Bechdel, Alison. Interview with Eva Sollberger. “Stuck in Vermont 109: Alison Bechdel.” YouTube. YouTube 13 Dec. 2008. Web. 6 Feb. 2009.

Chabani, Karim. “Double Trajectories: Crossing Lines in Fun Home.” GRAAT 1 March 2007: 1-14. Print.

Chute, Hillary. “An Interview with Alison Bechdel.” MFS Modern Fiction Studies 52.4 (2006): 1004-1013. Project Muse. Web. 30 Jan. 2009.

Gardner, Jared. “Autography’s Biography, 1972-2007.” Biography 31.1 (Winter 2008). Project Muse. Web. 11 Feb. 2009.

Magritte, René. The Treachery of Images. 1929. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. lacma.org. Web. 11 Feb. 2009.