Toulmin Argument

Toulmin Argument

130

In The Uses of Argument (1958), British philosopher Stephen Toulmin presented structures to describe the way that ordinary people make reasonable arguments. Because Toulmin’s system acknowledges the complications of life — situations when we qualify our thoughts with words such as sometimes, often, presumably, unless, and almost — his method isn’t as airtight as formal logic that uses syllogisms (see introduction to Chapter 7, “Structuring Arguments” in this chapter and “Using Reason and Common Sense” in Chapter 4, “Arguments Based on Facts and Reason: Logos.”). But for that reason, Toulmin logic has become a powerful and, for the most part, practical tool for understanding and shaping arguments in the real world.

Toulmin argument will help you come up with and test ideas and also figure out what goes where in many kinds of arguments. Let’s take a look at the basic elements of Toulmin’s structure:

| Claim | the argument you wish to prove |

| Qualifiers | any limits you place on your claim |

| Reason(s)/Evidence | support for your claim |

| Warrants | underlying assumptions that support your claim |

| Backing | evidence for warrant |

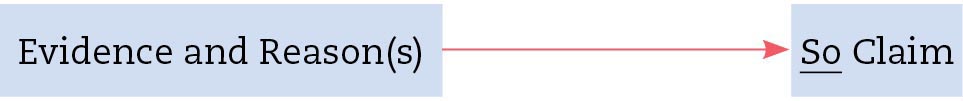

If you wanted to state the relationship between them in a sentence, you might say:

My claim is true, to a qualified degree, because of the following reasons, which make sense if you consider the warrant, backed by these additional reasons.

These terms — claim, evidence, warrants, backing, and qualifiers — are the building blocks of the Toulmin argument structure. Let’s take them one at a time.

Making Claims

Toulmin arguments begin with claims, debatable and controversial statements or assertions you hope to prove.

A claim answers the question So what’s your point? or Where do you stand on that? Some writers might like to ignore these questions and avoid stating a position. But when you make a claim worth writing about, then it’s worth standing up and owning it.

131

Is there a danger that you might oversimplify an issue by making too bold a claim? Of course. But making that sweeping claim is a logical first step toward eventually saying something more reasonable and subtle. Here are some fairly simple, undeveloped claims:

Congress should enact legislation that establishes a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants.

It’s time for the World Health Organization (WHO) to exert leadership in coordinating efforts to stem the Ebola epidemic in West Africa.

NASA should launch a human expedition to Mars.

Veganism is the most responsible choice of diet.

Military insurance should not cover the cost of sex change surgery for service men and women.

Good claims often spring from personal experiences. You may have relevant work or military or athletic experience — or you may know a lot about music, film, sustainable agriculture, social networking, inequities in government services — all fertile ground for authoritative, debatable, and personally relevant claims.

RESPOND •

Claims aren’t always easy to find. Sometimes they’re buried deep within an argument, and sometimes they’re not present at all. An important skill in reading and writing arguments is the ability to identify claims, even when they aren’t obvious.

Collect a sample of six to eight letters to the editor of a daily newspaper (or a similar number of argumentative postings from a political blog). Read each item, and then identify every claim that the writer makes. When you’ve compiled your list of claims, look carefully at the words that the writer or writers use when stating their positions. Is there a common vocabulary? Can you find words or phrases that signal an impending claim? Which of these seem most effective? Which ones seem least effective? Why?

Click to navigate to this activity.

Offering Evidence and Good Reasons

You can begin developing a claim by drawing up a list of reasons to support it or finding evidence that backs up the point.

Academic arguments such as “Playing with Prejudice: The Prevalence and Consequences of Racial Stereotypes in Video Games” by Melinda C. R. Burgess et al. often closely follow the Toulmin structure, making sure that their claims are well supported.

132

One student writer wanted to gather good reasons in support of an assertion that his college campus needed more official spaces for parking bicycles. He did some research, gathering statistics about parking-space allocation, numbers of people using particular designated slots, and numbers of bicycles registered on campus. Before he went any further, however, he listed his primary reasons for wanting to increase bicycle parking:

Personal experience: At least twice a week for two terms, he was unable to find a designated parking space for his bike.

Anecdotes: Several of his friends told similar stories. One even sold her bike as a result.

Facts: He found out that the ratio of car to bike parking spaces was 100 to 1, whereas the ratio of cars to bikes registered on campus was 25 to 1.

Authorities: The campus police chief told the college newspaper that she believed a problem existed for students who tried to park bicycles legally.

On the basis of his preliminary listing of possible reasons in support of the claim, this student decided that his subject was worth more research. He was on the way to amassing a set of good reasons and evidence that were sufficient to support his claim.

In shaping your own arguments, try putting claims and reasons together early in the writing process to create enthymemes. Think of these enthymemes as test cases or even as topic sentences:

Bicycle parking spaces should be expanded because the number of bikes on campus far exceeds the available spots.

It’s time to lower the driving age because I’ve been driving since I was fourteen and it hasn’t hurt me.

National legalization of marijuana is long overdue since it is already legal in over twenty states, has shown to be less harmful than alcohol, and provides effective relief from pain associated with cancer.

Violent video games should be carefully evaluated and their use monitored by the industry, the government, and parents because these games cause addiction and psychological harm to players.

As you can see, attaching a reason to a claim often spells out the major terms of an argument.

133

But your work is just beginning when you’ve put a claim together with its supporting reasons and evidence — because readers are certain to begin questioning your statement. They might ask whether the reasons and evidence that you’re offering really do support the claim: should the driving age really be changed just because you’ve managed to drive since you were fourteen? They might ask pointed questions about your evidence: exactly how do you know that the number of bikes on campus far exceeds the number of spaces available? Eventually, you’ve got to address potential questions about the quality of your assumptions and the quality of your evidence. The connection between claim and reason(s) is a concern at the next level in Toulmin argument.

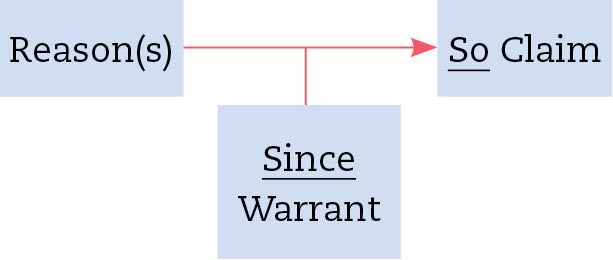

Determining Warrants

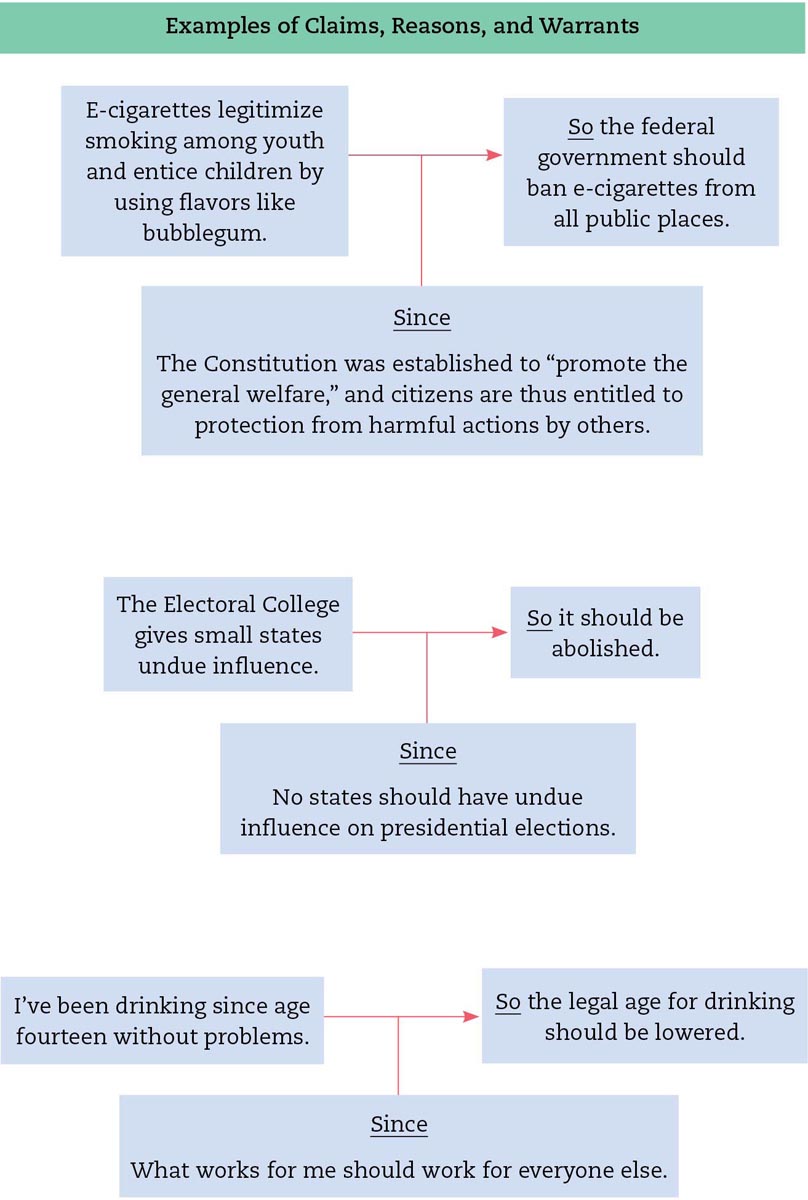

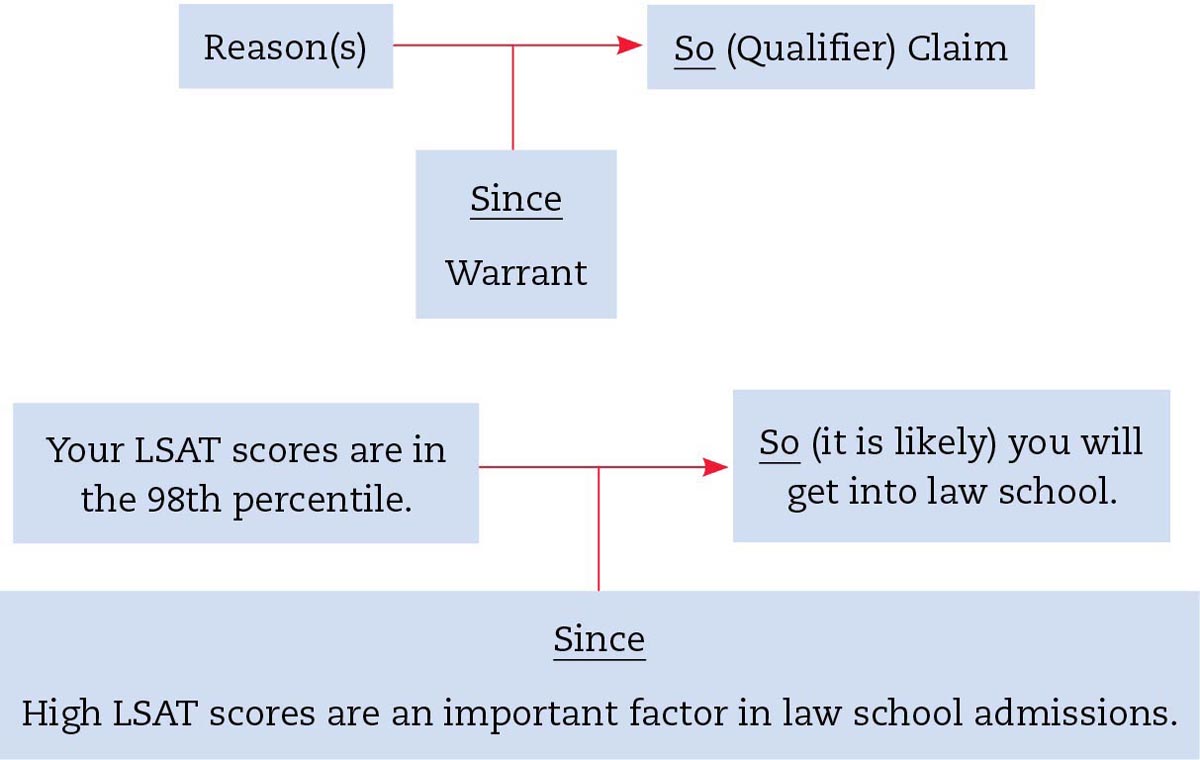

Crucial to Toulmin argument is appreciating that there must be a logical and persuasive connection between a claim and the reasons and data supporting it. Toulmin calls this connection the warrant. It answers the question How exactly do I get from the data to the claim? Like the warrant in legal situations (a search warrant, for example), a sound warrant in an argument gives you authority to proceed with your case.

134

The warrant tells readers what your (often unstated) assumptions are — for example, that any practice that causes serious disease should be banned by the government. If readers accept your warrant, you can then present specific evidence to develop your claim. But if readers dispute your warrant, you’ll have to defend it before you can move on to the claim itself.

In “Little Girls or Little Women? The Disney Princess Effect,” Stephanie Hanes interviews blogger and mom Mary Finucane, who believes that girls’ princess obsession is harmful to their development as strong women. What warrants lie behind this claim?

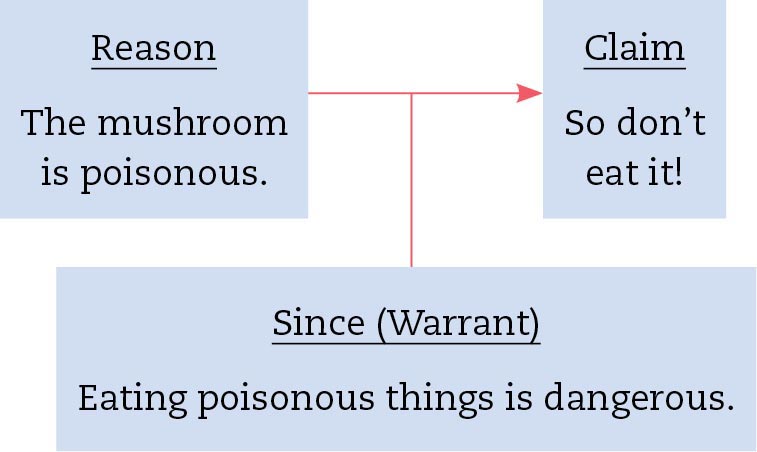

Stating warrants can be tricky because they can be phrased in various ways. What you’re looking for is the general principle that enables you to justify the move from a reason to a specific claim — the bridge connecting them. The warrant is the assumption that makes the claim seem believable. It’s often a value or principle that you share with your readers. Here’s an easy example:

Don’t eat that mushroom: it’s poisonous.

The warrant supporting this enthymeme can be stated in several ways, always moving from the reason (it’s poisonous) to the claim (Don’t eat that mushroom):

Anything that is poisonous shouldn’t be eaten.

If something is poisonous, it’s dangerous to eat.

Here’s the relationship, diagrammed:

135

Perfectly obvious, you say? Exactly — and that’s why the statement is so convincing. If the mushroom in question is a death cap or destroying angel (and you might still need expert testimony to prove that it is), the warrant does the rest of the work, making the claim that it supports seem logical and persuasive.

Let’s look at a similar example, beginning with the argument in its basic form:

We’d better stop for gas because the gauge has been reading empty for more than thirty miles.

In this case, you have evidence that is so clear (a gas gauge reading empty) that the reason for getting gas doesn’t even have to be stated: the tank is almost empty. The warrant connecting the evidence to the claim is also pretty obvious:

If the fuel gauge of a car has been reading empty for more than thirty miles, then that car is about to run out of gas.

Since most readers would accept this warrant as reasonable, they would also likely accept the statement the warrant supports.

Naturally, factual information might undermine the whole argument: the fuel gauge might be broken, or the driver might know that the car will go another fifty miles even though the fuel gauge reads empty. But in most cases, readers would accept the warrant.

Now let’s consider how stating and then examining a warrant can help you determine the grounds on which you want to make a case. Here’s a political enthymeme of a familiar sort:

Flat taxes are fairer than progressive taxes because they treat all taxpayers in the same way.

136

Warrants that follow from this enthymeme have power because they appeal to a core American value — equal treatment under the law:

Treating people equitably is the American way.

All people should be treated in the same way.

You certainly could make an argument on these grounds. But stating the warrant should also raise a flag if you know anything about tax policy. If the principle is obvious and universal, then why do federal and many progressive state income taxes require people at higher levels of income to pay at higher tax rates than people at lower income levels? Could the warrant not be as universally popular as it seems at first glance? To explore the argument further, try stating the contrary claim and warrants:

Progressive taxes are fairer than flat taxes because people with more income can afford to pay more, benefit more from government, and shelter more of their income from taxes.

People should be taxed according to their ability to pay.

People who benefit more from government and can shelter more of their income from taxes should be taxed at higher rates.

Now you see how different the assumptions behind opposing positions really are. If you decided to argue in favor of flat taxes, you’d be smart to recognize that some members of your audience might have fundamental reservations about your position. Or you might even decide to shift your entire argument to an alternative rationale for flat taxes:

Flat taxes are preferable to progressive taxes because they simplify the tax code and reduce the likelihood of fraud.

Here, you have two stated reasons that are supported by two new warrants:

Taxes that simplify the tax code are desirable.

Taxes that reduce the likelihood of fraud are preferable.

Whenever possible, you’ll choose your warrant knowing your audience, the context of your argument, and your own feelings.

Be careful, though, not to suggest that you’ll appeal to any old warrant that works to your advantage. If readers suspect that your argument for progressive taxes really amounts to I want to stick it to people who work harder than I, your credibility may suffer a fatal blow.

137

RESPOND •

138

At their simplest, warrants can be stated as “X is good” or “X is bad.” Return to the letters to the editor or blog postings that you analyzed in the exercise on “Making Claims” in Chapter 7, “Structuring Arguments,”, this time looking for the warrant that is behind each claim. As a way to start, ask yourself these questions:

If I find myself agreeing with the letter writer, what assumptions about the subject matter do I share with him/her?

If I disagree, what assumptions are at the heart of that disagreement?

The list of warrants you generate will likely come from these assumptions.

Click to navigate to this activity.

Offering Evidence: Backing

The richest, most interesting part of a writer’s work — backing — remains to be done after the argument has been outlined. Clearly stated claims and warrants show you how much evidence you will need. Take a look at this brief argument, which is both debatable and controversial, especially in tough economic times:

NASA should launch a human expedition to Mars because Americans need a unifying national goal.

Here’s one version of the warrant that supports the enthymeme:

What unifies the nation ought to be a national priority.

To run with this claim and warrant, you’d first need to place both in context. Human space exploration has been debated with varying intensity following the 1957 launch of the Soviet Union’s Sputnik satellite, after the losses of the U.S. space shuttles Challenger (1986) and Columbia (2003), and after the retirement of the Space Shuttle program in 2011. Acquiring such background knowledge through reading, conversation, and inquiry of all kinds will be necessary for making your case. (See Chapter 3 for more on gaining authority.)

139

There’s no point in defending any claim until you’ve satisfied readers that questionable warrants on which the claim is based are defensible. In Toulmin argument, evidence you offer to support a warrant is called backing.

Warrant

What unifies the nation ought to be a national priority.

Backing

Americans want to be part of something bigger than themselves. (Emotional appeal as evidence)

In a country as diverse as the United States, common purposes and values help make the nation stronger. (Ethical appeal as evidence)

In the past, government investments such as the Hoover Dam and the Apollo moon program enabled many — though not all — Americans to work toward common goals. (Logical appeal as evidence)

In addition to evidence to support your warrant (backing), you’ll need evidence to support your claim:

Argument in Brief (Enthymeme/Claim)

NASA should launch a human expedition to Mars because Americans now need a unifying national goal.

Evidence

The American people are politically divided along lines of race, ethnicity, religion, gender, and class. (Fact as evidence)

A common challenge or problem often unites people to accomplish great things. (Emotional appeal as evidence)

A successful Mars mission would require the cooperation of the entire nation — and generate tens of thousands of jobs. (Logical appeal as evidence)

A human expedition to Mars would be a valuable scientific project for the nation to pursue. (Appeal to values as evidence)

As these examples show, appeals to values and emotions can be just as appropriate as appeals to logic and facts, and all such claims will be stronger if a writer presents a convincing ethos. In most arguments, appeals work together rather than separately, reinforcing each other. (See Chapter 3 for more on ethos.)

Using Qualifiers

140

Experienced writers know that qualifying expressions make writing more precise and honest. Toulmin logic encourages you to acknowledge limitations to your argument through the effective use of qualifiers. You can save time if you qualify a claim early in the writing process. But you might not figure out how to limit a claim effectively until after you’ve explored your subject or discussed it with others.

Qualifiers |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| few | more or less | often | ||

| it is possible | in some cases | perhaps | ||

| rarely | many | under these conditions | ||

| it seems | typically | possibly | ||

| some | routinely | for the most part | ||

| it may be | most | if it were so | ||

| sometimes | one might argue | in general | ||

Never assume that readers understand the limits you have in mind. Rather, spell them out as precisely as possible, as in the following examples:

| Unqualified Claim | People who don’t go to college earn less than those who do. |

| Qualified Claim | In most cases, people who don’t go to college earn less than those who do. |

Understanding Conditions of Rebuttal

141

In the Toulmin system, potential objections to an argument are called conditions of rebuttal. Understanding and reacting to these conditions are essential to support your own claims where they’re weak and also to recognize and understand the reasonable objections of people who see the world differently. For example, you may be a big fan of the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) and the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and prefer that federal tax dollars be spent on these programs. So you offer the following claim:

| Claim | The federal government should support the arts. |

You need reasons to support this thesis, so you decide to present the issue as a matter of values:

| Argument in Brief | The federal government should support the arts because it also supports the military. |

Now you’ve got an enthymeme and can test the warrant, or the premises of your claim:

| Warrant | If the federal government can support the military, then it can also support other programs. |

But the warrant seems frail: you can hear a voice over your shoulder saying, “In essence, you’re saying that Because we pay for a military, we should pay for everything!” So you decide to revise your claim:

| Revised Argument | If the federal government can spend huge amounts of money on the military, then it can afford to spend moderate amounts on arts programs. |

Now you’ve got a new warrant, too:

| Revised Warrant | A country that can fund expensive programs can also afford less expensive programs. |

This is a premise that you can defend, since you believe strongly that the arts are just as essential as a strong military is to the well-being of the country. Although the warrant now seems solid, you still have to offer strong grounds to support your specific and controversial claim. So you cite statistics from reputable sources, this time comparing the federal budgets for the military and the arts. You break them down in ways that readers can visualize, demonstrating that much less than a penny of every tax dollar goes to support the arts.

142

But then you hear those voices again, saying that the “common defense” is a federal mandate; the government is constitutionally obligated to support a military, and support for the arts is hardly in the same league! Looks like you need to add a paragraph explaining all the benefits the arts provide for very few dollars spent, and maybe you should suggest that such funding falls under the constitutional mandate to “promote the general welfare.” Though not all readers will accept these grounds, they’ll appreciate that you haven’t ignored their point of view: you’ve gained credibility by anticipating a reasonable objection.

Dealing with conditions of rebuttal is an essential part of argument. But it’s important to understand rebuttal as more than mere opposition. Anticipating objections broadens your horizons, makes you more open to alternative viewpoints, and helps you understand what you need to do to support your claim.

Within Toulmin argument, conditions of rebuttal remind us that we’re part of global conversations: Internet newsgroups and blogs provide potent responses to positions offered by participants in discussions; instant messaging and social networking let you respond to and challenge others; links on Web sites form networks that are infinitely variable and open. In cyberspace, conditions of rebuttal are as close as your screen.

RESPOND •

Using an essay or a project you are composing, do a Toulmin analysis of the argument. When you’re done, see which elements of the Toulmin scheme are represented. Are you short of evidence to support the warrant? Have you considered the conditions of rebuttal? Have you qualified your claim adequately? Next, write a brief revision plan: How will you buttress the argument in the places where it is weakest? What additional evidence will you offer for the warrant? How can you qualify your claim to meet the conditions of rebuttal? Then show your paper to a classmate and have him/her do a Toulmin analysis: a new reader will probably see your argument in different ways and suggest revisions that may not have occurred to you.

Click to navigate to this activity.

143

Outline of a Toulmin Argument

Consider the claim that was mentioned in “Examples of Claims, Reasons, and Warrants” in Chapter 7, “Structuring Arguments”:

| Claim | The federal government should ban e-cigarettes. |

| Qualifier | The ban would be limited to public spaces. |

|

Good

Reasons |

E-cigarettes have not been proven to be harmless.

E-cigarettes legitimize smoking and also are aimed at recruiting teens and children with flavors like bubblegum and cotton candy. |

| Warrants |

The Constitution promises to “promote the general welfare.”

Citizens are entitled to protection from harmful actions by others. |

| Backing | The United States is based on a political system that is supposed to serve the basic needs of its people, including their health. |

| Evidence |

Analysis of advertising campaigns that reveal direct appeals to children

Lawsuits recently won against e-cigarette companies, citing the link between e-cigarettes and a return to regular smoking Examples of bans on e-cigarettes already imposed in many public places |

| Authority | Cite the FDA and medical groups on effect of e-cigarette smoking. |

| Conditions of Rebuttal |

E-cigarette smokers have rights, too.

Smoking laws should be left to the states. Such a ban could not be enforced. |

| Responses | The ban applies to public places; smokers can smoke in private. |

A Toulmin Analysis

144

You might wonder how Toulmin’s method holds up when applied to an argument that is longer than a few sentences. Do such arguments really work the way that Toulmin predicts? In the following short argument, well-known linguist and author Deborah Tannen explores the consequences of a shift in the meaning of one crucial word: compromise. Tannen’s essay, which originally appeared as a posting on Politico.com on June 15, 2011, offers a series of interrelated claims based on reasons, evidence, and warrants that culminate in the last sentence of the essay. She begins by showing that the word compromise is now rejected by both the political right and the political left and offers good reasons and evidence to support that claim. She then moves back to a time when “a compromise really was considered great,” and offers three powerful pieces of evidence in support of that claim. The argument then comes back to the present, with a claim that the compromise and politeness of the nineteenth century have been replaced by “growing enmity.” That claim is supported with reasoning and evidence that rest on an underlying warrant that “vituperation and seeing opponents as enemies is corrosive to the human spirit.” The claims in the argument — that compromise has become a dirty word and that enmity and an adversarial spirit are on the rise — lead to Tannen’s conclusion: rejecting compromise breaks the trust necessary for a democracy and thus undermines the very foundation of our society. While she does not use traditional qualifying words, she does say that the situation she describes is a “threat” to our nation, which qualifies the claim to some extent: the situation is not the “death” of our nation but rather a “threat.” Tannen’s annotated essay follows.