What’s Globalization Doing to Language?

24

What’s Globalization Doing to Language?

568

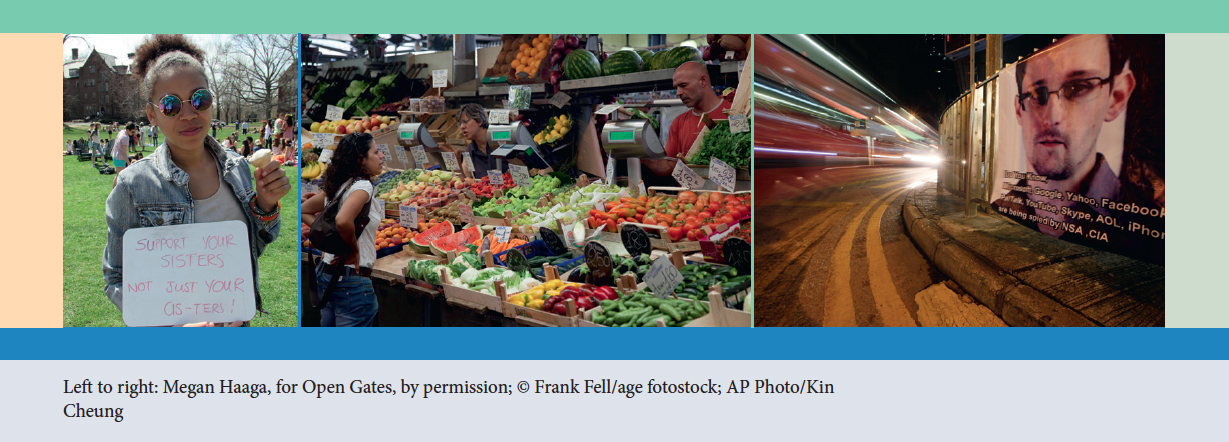

Globalization, or the deepening connections among nations, governments, companies, and individuals, is having an impact on all kinds of things — the food we eat, the people whom we end up with in class, and even the language(s) we speak. In this chapter, you’ll read selections investigating some of the many ways that globalization has consequences for language. Most of the time, we take language for granted. We treat it much like a glass windowpane, not even realizing it’s there until, of course, we meet someone who speaks a markedly different dialect or who doesn’t speak the language well or at all. In those situations, we’re reminded that language is much more than a mere medium of communication. It reflects who we are and aren’t and how we do and don’t want to be identified.

The chapter’s opening selection, an editorial from the Lebanon (PA) Daily News, comments on that most American of events, the Super Bowl. It focuses specifically on a commercial broadcast during the 2014 game, an ad for Coca-Cola that featured “America the Beautiful.” As you may recall, the lines of the song were sung in a variety of languages now found across the United States. The Twittersphere went wild, and this editorial responds to the controversy, asking some profound questions about what makes for a successful commercial and a successful country, especially where language and attitudes toward language are concerned.

569

The second selection, Kirk Semple’s newspaper article “Immigrants Who Speak Indigenous Languages Encounter Isolation,” considers the situation of immigrants to the United States from Spanish-speaking Latin America whose first language is not Spanish but, rather, an indigenous language. Because of where they live, they often find learning Spanish helps them integrate in the United States more quickly than would learning English. Obviously, these languages are adding to the complexity of our country’s linguistic mosaic.

Scott L. Montgomery focuses on a very different consequence of globalization — the use of English as the global language in the field of science. Because the most prestigious scientific journals are published in English-speaking countries, scientists around the world who want to share their research with colleagues must do so in English. While such a situation encourages the exchange of ideas and information, it also has its downsides, as Montgomery discusses. Interestingly, he argues that the biggest losers may be those of us who speak English as our first and often only language.

“Infographic: Speak My Language” by Santos Henarejos presents a visual argument that highlights some of the side effects of globalization for language, such as the ways that the availability of technology influences how we communicate, including the languages we use.

Picking up a topic mentioned by Montgomery, Nicholas Ostler asks whether globalization is the reason many “small” languages are disappearing. Depending on whom you ask, you’ll hear that there are some six thousand languages spoken in the world today, but given the growing influence of more widely spoken languages, as few as six hundred of them will likely still be spoken a century from now. Many are quick to blame globalization as the reason for this loss; Ostler, who is chair of the Foundation for Endangered Languages, contends that globalization alone is not the culprit.

Finally, Rose Eveleth’s “Saving Languages through Korean Soap Operas” investigates what at first seems like a wacky idea: crowd-sourcing the subtitling of television programs into these small languages as a way of encouraging their maintenance and use — that is, creating reasons for people to learn them. These last two articles remind us that mutually reinforcing, complex forces like technology and globalization can work in amazing and unpredictable ways.