How Has the Internet Changed the Meaning of Privacy?

27

How Has the Internet Changed the Meaning of Privacy?

732

The last time you downloaded a software update, did you stop to read the agreement listing the rights and information you were giving away when you clicked ACCEPT? Likely not. Even if you had, odds are you would’ve realized that given our reliance on (and addiction to) technology, we have little choice but to “share” all sorts of information about who we are and what we do online — and to do so freely. But there is also the issue of the information we don’t give away, information that someone — governments and big corporations, for example — manages to obtain about our online and offline selves, whether they do so legally, illegally, or in that gray space in between. The selections in this chapter give you a chance to investigate these issues and the impact they have on you as someone who depends on technology.

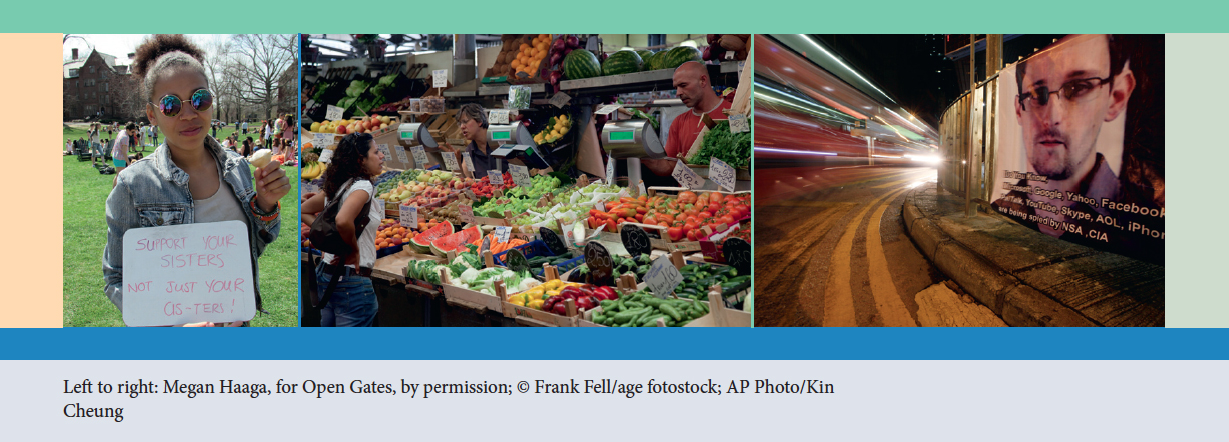

The chapter opens with a selection from Daniel J. Solove’s 2011 book, Nothing to Hide: The False Tradeoff between Privacy and Security. Solove, a law professor, does his best to demolish the argument that most of us needn’t worry about issues of privacy online because we’re law-abiding citizens with nothing to hide. The second selection, Rebecca Greenfield’s “What Your Email Metadata Told the NSA about You,” explains and illustrates the important concept of metadata and how it can be used by organizations like the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA). As you’ll see when you geolocate yourself, every time you use a computer, someone somewhere could be learning all sorts of things about you. The third selection, the chapter’s visual argument, asks you to analyze three cartoons dealing with privacy and government surveillance.

733

The next two selections consider privacy and surveillance with respect to technology companies in particular. In an excerpt from their conference paper Six Provocations for Big Data, researchers danah boyd (who spells her name all lowercase) and Kate Crawford explain what constitutes “Big Data,” how such data can be used, and why all of us should be paying attention to who gets access to it. “It’s Not OK Cupid,” an interview from The Takeaway, a Public Radio International program, gives Christian Rudder, co-founder of OkCupid, a popular dating site, a chance to defend experiments his site conducted on its unsuspecting users, manipulating the messages they received about good and bad matches. (After listening to the program and reading the transcript, you may want to say that program host Todd Zwillich takes Rudder to task for what his company did, demonstrating the very different conclusions individuals with different assumptions about privacy come to about what Rudder would label “business as usual.”)

The final two selections in the chapter return to the question of privacy and the government, but the focus is a 2014 Supreme Court ruling in Riley v. California, which made it illegal for law enforcement officials to search the contents of someone’s cell phone without first obtaining a warrant. This narrowing of the rights of law enforcement with regard to searches of cell phones represents a major victory for privacy advocates — at least in certain situations. The final selection in the chapter, Amy Davidson’s “Four Ways the Riley Ruling Matters for the NSA,” argues that the Riley ruling will have major consequences for continuing debates and court cases about the behavior of the NSA, although she also admits that not everyone agrees.

So who’s watching over your shoulder as you type away, and what do they see that you likely don’t realize is visible? The selections in this chapter will give you new perspectives on what it means to be wired and on the tradeoffs you’re making, whether or not you realize it.