What Your Email Metadata Told the NSA about You

Rebecca Greenfield is currently a staff writer at Fast Company, an award-winning magazine and Web site about technology, business, and design. Formerly, she was a staff writer at the Atlantic Wire, where her focus was technology and where this selection first appeared in June 2013. (The Atlantic Wire, now the Wire, is still associated with the Atlantic magazine and includes original reporting as well as news and opinion pieces aggregated from a number of media outlets.) As you read this selection, consider how Daniel J. Solove, author of the previous selection, “The Nothing-to-Hide Argument,” might respond to it; you might also consider a comment posted on the Wire Web site in response to this article: “the point is that if they can get their hands on the headers, they certainly can read the message content too.”

What Your Email Metadata Told the NSA about You

REBECCA GREENFIELD

746

President Obama said “nobody is listening to your telephone calls,” even though the National Security Agency could actually track you from cellphone metadata. Well, the latest from the Edward Snowden leaks shows that Obama eventually told the NSA to stop collecting your email communications in 2011, apparently because the so-called StellarWind program “was not yielding much value,” even when collected in bulk. But how much could the NSA learn from all that email metadata, really? And was it more invasive than phone data collection? The agency is well beyond its one trillionth metadata record, after all, so they must have gotten pretty good at this.

747

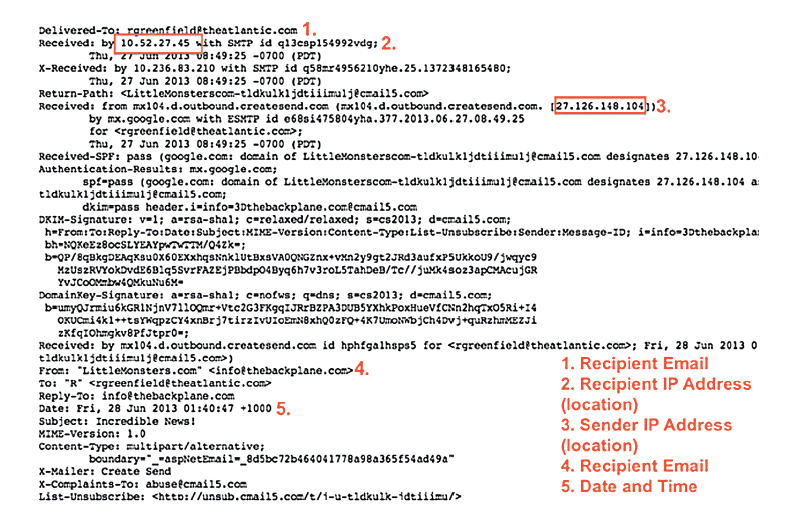

To offer a basic sense of how StellarWind collection worked — and how much user names and IP addresses can tell a spy about a person, even if he’s not reading the contents of your email — we took a look at the raw source code of an everyday email header. It’s not the exact kind of information the NSA was pulling, of course, but it shows the type of information attached to every single one of your emails.

Below is what the metadata looks like as it travels around with an email — we’ve annotated the relevant parts, based on what the Guardian reported today as the legally allowed (and apparently expanded) powers of the NSA to read without your permission. After all, it’s right there behind your words:

748

As you can see, at the bare minimum, your average email metadata offers location (through the IPs), plus names (or at least email addresses), and dates (down to the second). The Guardian’s Glenn Greenwald and Spencer Ackerman report that Attorney General Michael Mukasey and Defense Secretary Bob Gates signed a document that OK’d the collection and mining of “the information appearing on the ‘to,’ ‘from,’ or ‘bcc’ lines of a standard email or other electronic communication” from, well, you and your friends and maybe some terrorists.

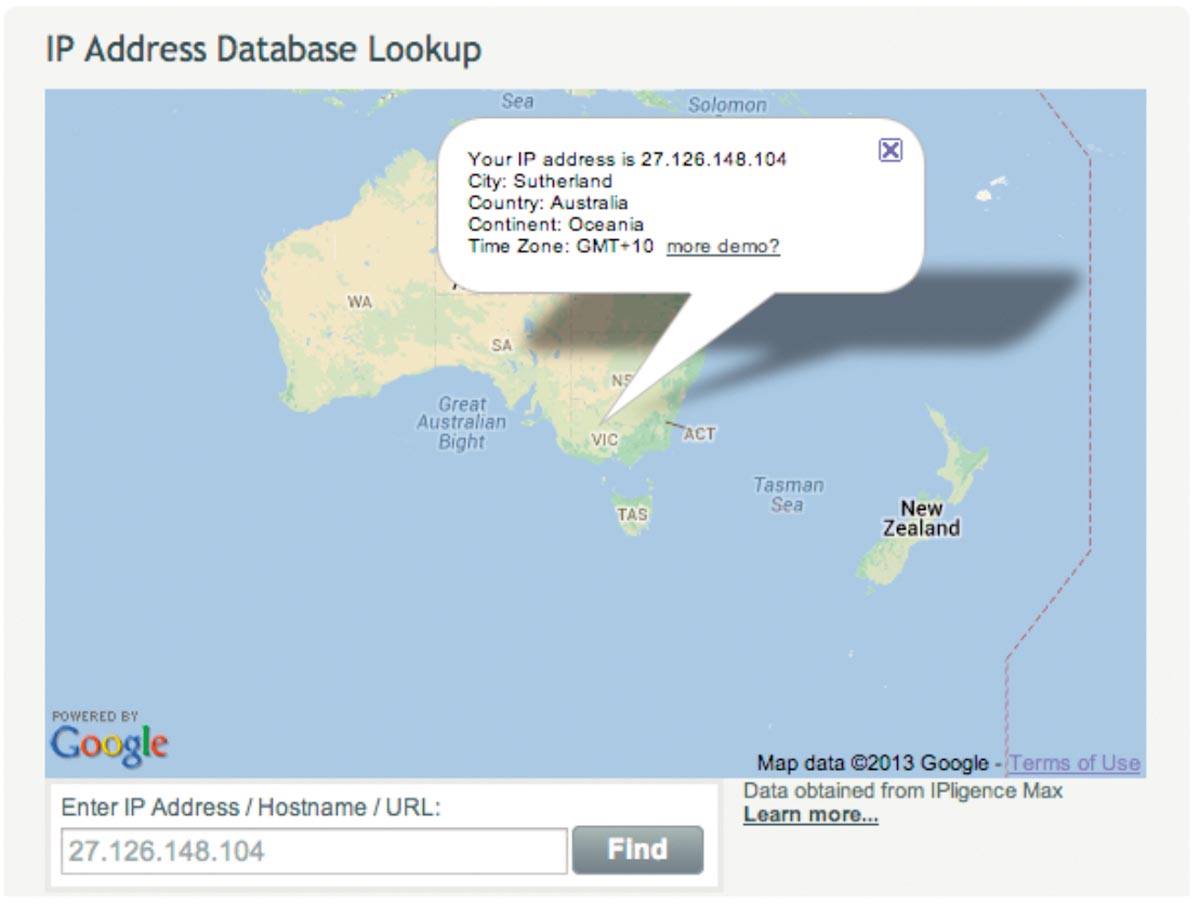

5 But email metadata is more revealing than that — even more revealing than what the NSA could do with just the time of your last phone call and the nearest cell tower. For operation StellarWind, it must have been all about that IP, or Internet protocol, address. Hell, it’d be easy enough for your grandma to geolocate both parties from a couple of IPs: there are countless free services on Google that turn those numbers you give to the IT guy into your exact location. For example, using the two IP addresses in the email sent to me above, we can easily determine that it was sent from Victoria, Australia:

The IP address is like a homing pigeon, and that’s why the revelations of email metadata being authorized under the Bush and Obama administrations amount to a seriously revealing breach of personal security in the name of terror-hunting. “Seeing your IP logs — and especially feeding them through sophisticated analytic tools — is a way of getting inside your head that’s in many ways on par with reading your diary,” Julian Sanchez of the Cato Institute told the Guardian. Of course, the administration has another party line, telling the Los Angeles Times that operation StellarWind was discontinued because it wasn’t adding up to enough good intelligence of “value.” But with one of the many “sophisticated analytic tool” sets developed by the NSA over the last decade or so and leaked during the last month — like, say, EvilOlive, “a near-real-time metadata analyzer” described in yet another Guardian scoop today — America’s intelligence operation certainly can zero in on exactly where Americans are. Even if you’re just emailing your hip grandma.

749

RESPOND •

Was the information presented in this selection new to you? Why or why not? How would you expect privacy advocates to respond to this selection? And what about those who argue that, in the name of national defense, the U.S. government needs to collect such data? How do you anticipate that Daniel J. Solove, author of the previous selection, “The Nothing-to-Hide Argument,” would respond? Why?

How would you characterize this selection: is it an argument of fact, of definition, or of evaluation; a causal argument; or a proposal argument? (The discussion of kinds of arguments in Chapter 1 will help you decide.) How would you characterize its function or purpose? (Chapter 6 on rhetorical analysis may help you here.)

Greenfield, like many people who write professionally for various Internet sites, uses a complex mix of styles: some parts of the article are quite informal while other parts could be part of an academic research paper. Choose several instances of particularly informal writing that would not be appropriate in an academic research paper, and explain why. How does Greenfield use comments about “grandma” to help structure the selection’s argument? (Chapter 13 discusses style in argument.)

Visual arguments play an important role in this selection. Evaluate the role that each of the visual arguments plays by discussing how the selection would have been different without it. (Chapter 14 on visual rhetoric will help you respond to this question.)

When Edward Snowden released confidential data from the NSA in 2013, he was immediately labeled a traitor by some and a hero by others. Collect and examine examples of discussions of Snowden — the comments posted in the Wire about this selection would be an easy place to begin — and write an evaluative argument in which you describe and evaluate the criteria used in making such an assessment by one side or the other. (In other words, your task is not to evaluate Snowden or his actions but to examine and evaluate the criteria his supporters or detractors used in reaching that conclusion.) An interesting challenge would be first to assess your own response to Snowden’s actions and second to evaluate the criteria used by those who share your opinion of his actions to come to such a conclusion. Doing so will require you to examine the tradeoffs you’re willing to make in balancing competing interests when the debate is about privacy. (Chapter 10 on evaluative arguments will help you consider and evaluate the criteria used in these discussions.)

Click to navigate to this activity.