11a Edit.

Once you have revised a draft for content and organization, look closely at your sentences and words. Turning a “blah” sentence into a memorable one—or finding exactly the right word to express a thought—can result in writing that is really worth reading. As with life, variety is the spice of sentences. You can add variety to your sentences by looking closely at their length, structure, and opening patterns.

Go to the Thinking Visually exercise to analyze this image

Sentence length

Too many short sentences, especially one following another, can sound like a series of blasts on a car horn, whereas a steady stream of long sentences may tire or confuse readers. Most writers aim for some variety in length, breaking up a series of fairly long sentences with a very brief one.

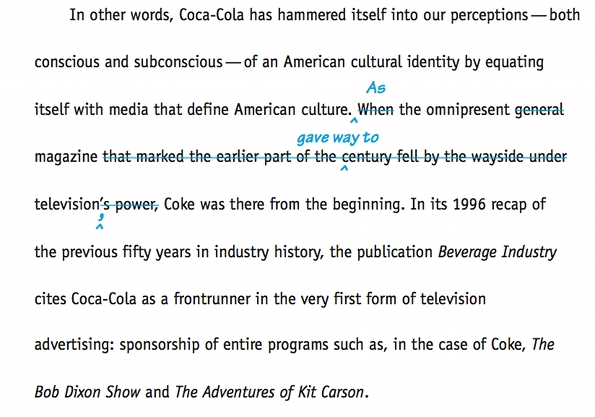

In examining the following paragraph from her essay, Emily Lesk discovered that the sentences were all fairly long. In editing, she decided to shorten the second sentence, thereby offering a shorter sentence between two long ones.

Student Writing

Sentence openings

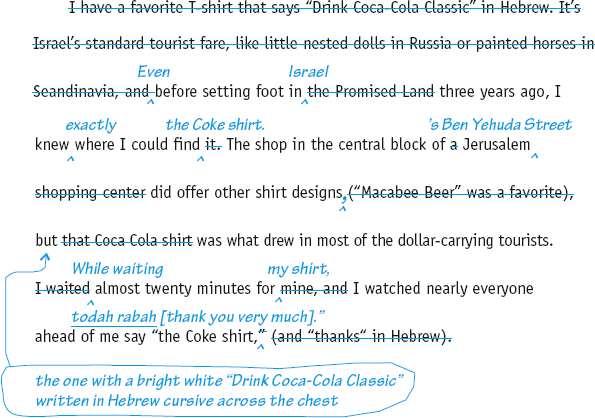

Opening sentence after sentence in the same way results in a jerky, abrupt, or choppy rhythm. You can vary sentence openings by beginning with a dependent clause, a phrase, an adverb, a conjunctive adverb, or a coordinating conjunction (30b). Another paragraph in Emily Lesk’s essay tells the story of how she got her Coke T-shirt in Israel. Before she revised, every sentence in the paragraph opened with the subject, so Emily decided to delete some examples and vary her sentence openings. The final version (which also appears in 5g) is a dramatic and easy-to-read paragraph.

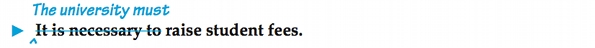

Opening with it and there

As you go over the opening sentences of your draft, look especially at those beginning with it or there. Sometimes these words can create a special emphasis, as in It was a dark and stormy night. But they can also appear too often. Another, more subtle problem with these openings is that they may be used to avoid taking responsibility for a statement. The following sentence can be improved by editing:

Tone

Tone refers to the attitude that a writer’s language conveys toward the topic and the audience. In examining the tone of your draft, think about the nature of the topic, your own attitude toward it, and that of your intended audience. Does your language create the tone you want to achieve (humorous, serious, impassioned, and so on), and is that tone an appropriate one, given your audience and topic?

Word choice

Word choice—or diction—offers writers an opportunity to put their personal stamp on a piece of writing. Becoming aware of the kinds of words you use should help you get the most mileage out of each word. Check for connotations, or associations, of words and make sure you consider how any use of slang, jargon, or emotional language may affect your audience (see 23a–b).

Spell checkers

While these software tools won’t catch every spelling error or identify all problems of style, they can be very useful. Most professional writers use their spell checkers religiously. Remember, however, that spell checkers are limited; they don’t recognize most proper names, foreign words, or specialized language, and they do not recognize homonym errors (misspelling there as their, for example). (See 23e.)

Document design

Before you produce a copy for final proofreading, reconsider one last time the format and the “look” you want your document to have. This is one last opportunity to think carefully about the visual appearance of your final draft. (For more on document design, see Chapter 9. For more on the design conventions of different disciplines, see Chapters 61–65.)

Word Choice

AT A GLANCE

- Are the nouns primarily abstract and general or concrete and specific? Too many abstract and general nouns can result in boring prose.

- Are there too many nouns in relation to the number of verbs? This sentence is heavy and boring: The effect of the overuse of nouns in writing is the placement of strain on the verbs. Instead, say this: Overusing nouns places a strain on the verbs.

- How many verbs are forms of be–be, am, is, are, was, were, being, been? If be verbs account for more than about a third of your total verbs, you are probably overusing them.

- Are verbs active wherever possible? Passive verbs are harder to read and remember than active ones. Although the passive voice has many uses, your writing will gain strength and energy if you use active verbs.

- Are your words appropriate? Check to be sure they are not too fancy–or too casual.

Proofreading the final draft

Take time for one last, careful proofreading, which means reading to correct any typographical errors or other inconsistencies in spelling and punctuation. To proofread most effectively, read through the copy aloud, making sure that you’ve used punctuation marks correctly and consistently, that all sentences are complete (unless you’ve used intentional fragments or run-ons for special effects)—and that no words are missing. Then go through the copy again, this time reading backward so that you can focus on each individual word and its spelling.

A student’s revised draft

Following are the first three paragraphs from Emily Lesk’s edited and proofread draft that she submitted to her instructor. Compare these paragraphs with those from her reviewed draft in 10b.

Emily Lesk

Professor Arráez

Electric Rhetoric

November 15, 2011

Red, White, and Everywhere

America, I have a confession to make: I don’t drink Coke. But don’t call me a hypocrite just because I am still the proud owner of a bright red shirt that advertises it. Just call me an American.

Student Writing

Even before setting foot in Israel three years ago, I knew exactly where I could find the Coke shirt. The shop in the central block of Jerusalem’s Ben Yehuda Street did offer other shirt designs, but the one with a bright white “Drink Coca-Cola Classic” written in Hebrew cursive across the chest was what drew in most of the dollar-carrying tourists. While waiting almost twenty minutes for my shirt (depicted in Fig. 1), I watched nearly everyone ahead of me say “the Coke shirt, todah rabah [thank you very much].”

At the time, I never thought it strange that I wanted one, too. After having absorbed sixteen years of Coca-Cola propaganda through everything from NBC’s Saturday morning cartoon lineup to the concession stand at Camden Yards (the Baltimore Orioles’ ballpark), I associated the shirt with singing along to the “Just for the Taste of It” jingle and with America’s favorite pastime, not with a brown fizzy beverage I refused to consume. When I later realized the immensity of Coke’s corporate power, I felt somewhat manipulated, but that didn’t stop me from wearing the shirt. I still don it often, despite the growing hole in the right sleeve, because of its power as a conversation piece. Few Americans notice it without asking something like “Does that say Coke?” I usually smile and nod. Then they mumble a one-word compliment, and we go our separate ways. But rarely do they want to know what language the internationally recognized logo is written in. And why should they? They are interested in what they can relate to as Americans: a familiar red-and-white logo, not a foreign language. Through nearly a century of brilliant advertising strategies, the Coca-Cola Company has given Americans not only a thirst-quenching beverage but a cultural icon that we have come to claim as our own.