49b Identify the type of source you are using.

Before you can decide how to cite your source following MLA guidelines, you need to determine what kind of source you’re using. This task can be surprisingly difficult. Citing a print book may seem relatively easy (though dizzying complications can arise—such as if the book has an editor or a translator, multiple editions, or chapters written by different people, to name a few possibilities). But citing digital sources may be especially mystifying. How, for instance, can you tell a Web site from a database you access online? What if your digital source reuses material from another source? Who publishes a digital text? Taking a step-by-step approach can help you solve such puzzles.

Print, digital, and other media sources

If your source has printed pages—a book or a newspaper, for instance—and you read the print version, you should look at the Directory to MLA Style on p. 470 for information on citing a print source. If the print source is a regularly issued journal, magazine, or newspaper (look for a date or seasonal information such as “Spring 2012” on the cover or first page), consider it a periodical rather than a book.

Be careful, however. If you access the digital version of a magazine or newspaper article, or if you read a book on an e-reader device such as a Kindle, then you should cite your source not as a print text but as a digital one. A digital version of a source may include updates or corrections that the print version lacks, so MLA guidelines require you to indicate your mode of access and to cite print and digital sources differently. Make sure to provide the correct information!

When you need to cite a source that consists mainly of material other than written words—such as a film, song, or artwork—you will need to provide additional information about how you encountered the material. See the Directory to MLA Style on p. 471 for more information on citing multimedia sources.

Articles from Web and database sources

Many students wonder how to distinguish between a Web source and a source from a database. Both, after all, can be reached from a computer (if you have home access to your school library’s online resources, you may be able to reach databases from any wired location). But guidelines for citing articles from the two types of sources are different, and so are considerations for using each type of writing.

DATABASE SOURCES

You need a subscription to look through most databases, so individual researchers almost always gain access to articles in databases through the computer system of a school or community library that pays to subscribe. The easiest way to tell whether a source comes from a database, then, is that its information is not available for free to anyone with an Internet connection. Many databases are digital collections of articles that originally appeared in print periodicals. The articles generally have the same written-word content as they did in print form, without changes or updates (some databases omit illustrations that appear in the print versions of articles, but others upload articles as PDFs that show not just words and illustrations but also the original print layout and page numbering). Print periodicals have editors, and some journals are peer-reviewed by experts in a field, ensuring that an authority vouches for the accuracy of the information. Finding information in an article from a database does not guarantee its credibility, but such information often has more authority behind it than much of what you find for free on the Web.

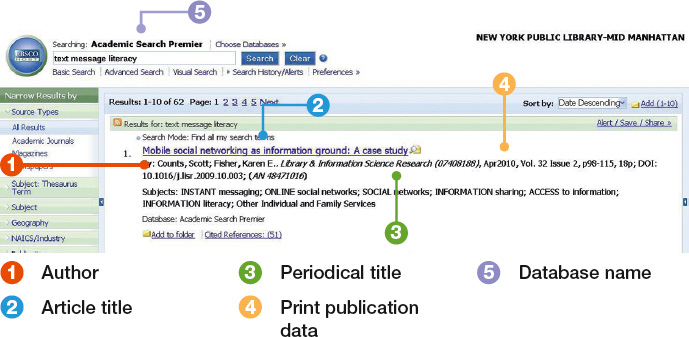

David Craig, whose research writing appears in Chapter 52, found the following source in Academic Search Premier, a database he accessed through a library Web site. From this page he was able to click through to the full text of the article. He printed this computer screen in case he needed to cite the article; the image includes all the information (other than his date of access) that he would need to create a complete MLA citation for an article from a database. Including the original print publication information for the article and the name of the database allows any reader who can access the database to locate the same article.

A SOURCE FROM A DATABASE

WEB SOURCES

Almost anyone can create a page on the Web, and information posted there often has not been verified by anyone. Therefore, MLA guidelines ask you to identify the publisher or sponsor for any work from a Web site that you cite in your writing. Information about sponsors and publishers often appears at the bottom of a page, on a home page, or in a separate “About” section on a reputable Web site (see pp. 212–13 in Chapter 17 for details on evaluating Web sources).

If the site doesn’t identify a sponsor or publisher, you may still use it (see pp. 490–91), but you should do more digging to find out about the site’s creator, and you would be wise to verify information on such a site before including it in your own text. David Craig looked at a Web site called “Text Message 101” while doing his preliminary research; although no author was identified, the information seemed useful. But when he noticed that the site’s sponsor was a cell phone provider using the site to sell phone plans, he decided against using the source in his writing project.

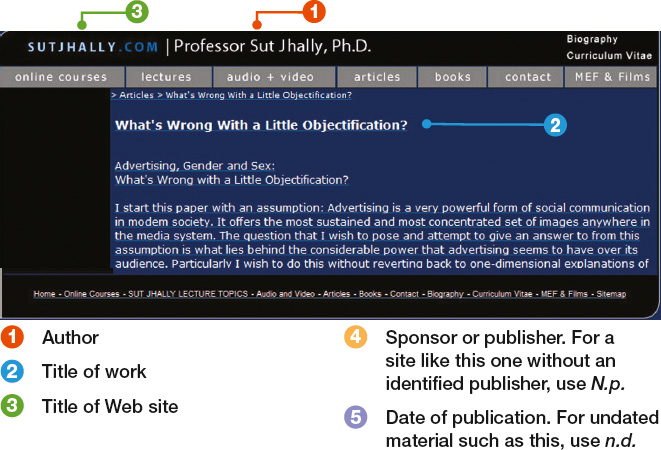

Teal Pfeifer, whose paper on how media messages affect body image appears in Chapter 14, downloaded this article by Dr. Sut Jhally, a professor of media studies, from the author’s personal Web site.

A WORK FROM A WEB SITE

Web sources for content beyond the written word

Many sources used in academic writing consist mainly of written words, presented either in print or in digital form. But you may also want to include sources in which images and other media are at least as important as written words. Figuring out which model to follow for media sources that appear online can pose additional questions.

While researching her PowerPoint presentation on Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir Fun Home (see Chapter 3), Shuqiao Song came across a brief video interview with Bechdel on YouTube that she wanted to play for her audience. However, the YouTube post noted that the interview had originally appeared on a video log called Stuck in Vermont and that this interview grew out of, and included passages from, a print interview from a small local print publication. (This kind of complicated backstory is by no means unusual for online media.) Shuqiao had to decide whether the video clip was most like a video, an interview, a work from a Web site, or something else entirely. After consulting with her instructor, she decided to give the full citation for the source as a work from a Web site (see the source map), since a YouTube citation seemed likely to make the source most accessible to those who saw her presentation. (For advice on making such decisions when no exact model is available, see the box.)