12.2 Antisocial Relations

462

Social psychology studies how we think about and influence one another, and also how we relate to one another. What are the roots of prejudice? What causes us to harm, or to help, or to fall in love? How can we move a destructive conflict toward a just peace? In this section we ponder insights into antisocial relations gleaned by researchers who have studied prejudice and aggression.

Prejudice

12-

prejudice an unjustifiable (and usually negative) attitude toward a group and its members. Prejudice generally involves stereotyped beliefs, negative feelings, and a predisposition to discriminatory action.

Prejudice means “prejudgment.” It is an unjustifiable and usually negative attitude toward a group—

stereotype a generalized (sometimes accurate but often overgeneralized) belief about a group of people.

beliefs (in this case, called stereotypes).

emotions (for example, hostility or fear).

predispositions to action (to discriminate).

Some stereotypes may be at least partly accurate. If you presume that young men tend to drive faster than elderly women, you may be right. People perceive Australians as having a rougher culture than the British, and in one analysis of millions of Facebook status updates, Australians did use more profanity (Kramer & Chung, 2011). But stereotypes can exaggerate—

discrimination unjustifiable negative behavior toward a group and its members.

Stereotypes can also bias behavior. To believe that obese people are gluttonous, and to feel dislike for an obese person, is to be prejudiced; prejudice is a negative attitude. To pass over all the obese people on a dating site, or to reject an obese person as a potential job candidate, is to discriminate; discrimination is a negative behavior.

How Prejudiced Are People?

Prejudice comes as both explicit (overt) and implicit (automatic) attitudes toward people of a particular ethnic group, gender, sexual orientation, or viewpoint. Some examples:

EXPLICIT ETHNIC PREJUDICE Americans’ expressed racial attitudes have changed dramatically in the last half-

Yet as overt prejudice wanes, subtle prejudice lingers. Despite increased verbal support for interracial marriage, many people admit that in socially intimate settings (dating, dancing, marrying), they, personally, would feel uncomfortable with someone of another race. And many people who say they would feel upset with someone making racist slurs actually, when hearing such racism, respond indifferently (Kawakami et al., 2009). Subtle prejudice may also take the form of “microaggressions,” such as race-

463

IMPLICIT ETHNIC PREJUDICE As we have seen throughout this book, the human mind processes thoughts, memories, and attitudes on two different tracks. Sometimes that processing is explicit—on the radar screen of our awareness. To a much greater extent, it is implicit—below the radar, leaving us unaware of how our attitudes are influencing our behavior. Modern studies indicate that prejudice is often implicit, an automatic attitude—

IMPLICIT RACIAL ASSOCIATIONS Using Implicit Association Tests, researchers have demonstrated that even people who deny harboring racial prejudice may carry negative associations (Banaji & Greenwald, 2013). For example, 9 in 10 White respondents took longer to identify pleasant words (such as peace and paradise) as “good” when presented with Black-

Although the test is useful for studying automatic prejudice, critics caution against using it to assess or label individuals (Oswald et al., 2013, 2015). Defenders counter that implicit biases predict behaviors ranging from simple acts of friendliness to the evaluation of work quality (Greenwald et al., 2015). In the 2008 U.S. presidential election, those demonstrating explicit or implicit prejudice were less likely to vote for candidate Barack Obama. His election in turn served to reduce implicit prejudice (Bernstein et al., 2010; Payne et al., 2010; Stephens-

UNCONSCIOUS PATRONIZATION In one experiment, White university women assessed flawed student essays. When assessing essays supposedly written by White students, the women gave low evaluations, often with harsh comments, but not so when the same essays were said to have been written by Black students (Harber, 1998). Did the evaluators calibrate their evaluations to their racial stereotypes, leading to less exacting standards and a patronizing attitude? In real-

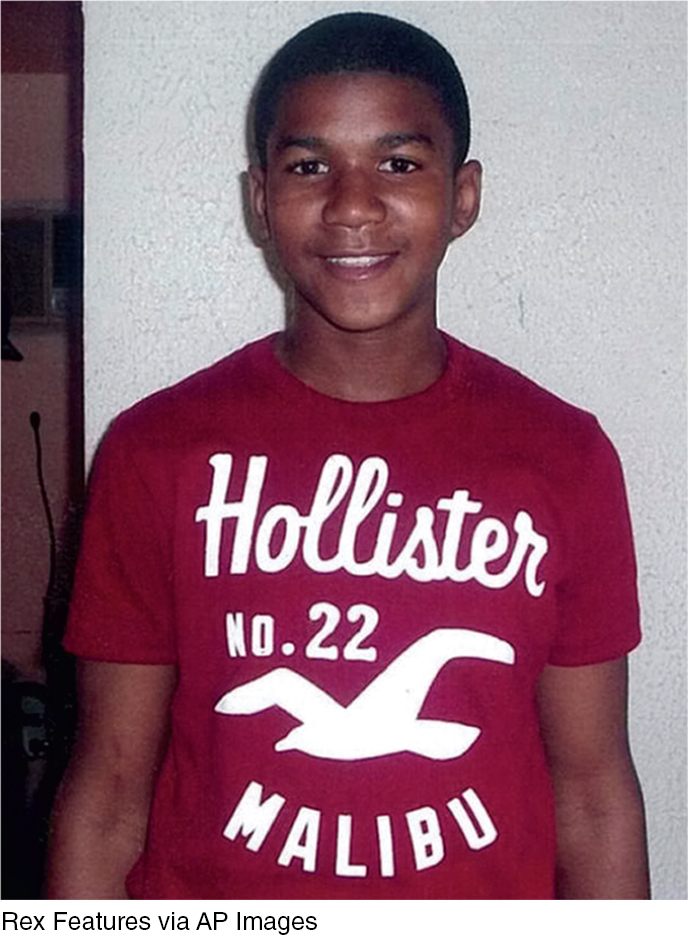

RACE-

464

In 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court, in upholding the Fair Housing Act, affirmed implicit bias research when noting that “unconscious prejudices” can cause discrimination even without conscious discriminatory intent. If your own gut-

GENDER PREJUDICE Overt gender prejudice has also declined sharply. The one-

But gender prejudice and discrimination persist. Despite equality between the sexes in intelligence scores, people have tended to perceive their fathers as more intelligent than their mothers (Furnham & Wu, 2008). We pay more to those (usually men) who care for our streets than to those (usually women) who care for our children. Worldwide, women are more likely to live in poverty (UN, 2010); they represent nearly two-

Unwanted female infants are no longer left out on a hillside to die of exposure, as was the practice in ancient Greece. Yet natural female mortality and the normal male-

SEXUAL ORIENTATION PREJUDICE In most of the world, gay and lesbian people cannot openly and comfortably disclose who they are and whom they love (Katz-

Do attitudes and practices that label, disparage, and discriminate against gay and lesbian people increase their risk of psychological disorder and ill health? In U.S. states without protections against LGBT hate crimes and discrimination, gay and lesbian people experience substantially higher rates for depression and related disorders, even after controlling for income and education differences. In communities where anti-

Social Roots of Prejudice

465

Why does prejudice arise? Social inequalities and divisions are partly responsible.

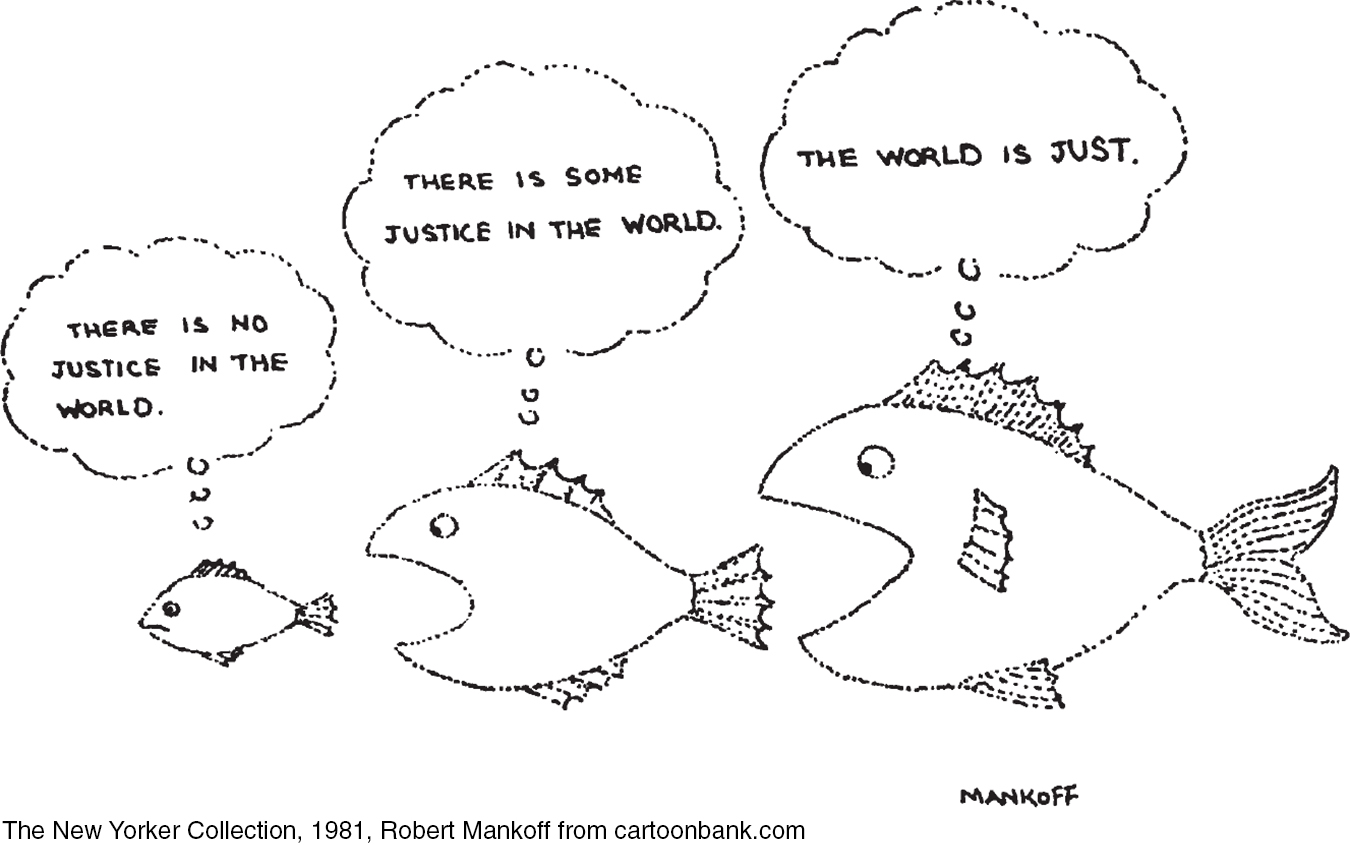

just-world phenomenon the tendency for people to believe the world is just and that people therefore get what they deserve and deserve what they get.

SOCIAL INEQUALITIES When some people have money, power, and prestige and others do not, the “haves” usually develop attitudes that justify things as they are. The just-world phenomenon reflects an idea we commonly teach our children—

Victims of discrimination may react in ways that feed prejudice through the classic blame-

US AND THEM: INGROUP AND OUTGROUP We have inherited our Stone Age ancestors’ need to belong, to live and love in groups. There was safety in solidarity (those who didn’t band together left fewer descendants). Whether hunting, defending, or attacking, 10 hands were better than 2. Dividing the world into “us” and “them” entails prejudice and war, but it also provides the benefits of communal solidarity. Thus, we cheer for our groups, kill for them, die for them. Indeed, we define who we are partly in terms of our groups. Through our social identities we associate ourselves with certain groups and contrast ourselves with others (Dunham et al., 2013; Hogg, 1996, 2006; Turner, 1987, 2007). When Ian identifies himself as a man, an Aussie, a University of Sydney student, a Catholic, and a MacGregor, he knows who he is, and so do we.

ingroup “us”—people with whom we share a common identity.

outgroup “them”—those perceived as different or apart from our ingroup.

ingroup bias the tendency to favor our own group.

Evolution prepared us, when encountering strangers, to make instant judgments: friend or foe? Those from our group, those who look like us, and also those who sound like us—

466

The urge to distinguish enemies from friends predisposes prejudice against strangers (Whitley, 1999). To Greeks of the classical era, all non-

“For if [people were] to choose out of all the customs in the world [they would] end by preferring their own.”

Greek historian Herodotus, 440 B.C.E.

Ingroup bias explains the cognitive power of political partisanship (Cooper, 2010; Douthat, 2010). In the United States in the late 1980s, most Democrats believed inflation had risen under Republican president Ronald Reagan (it had dropped). In 2010, most Republicans believed that taxes had increased under Democratic president Barack Obama (for most, they had decreased).

RETRIEVE IT

Question

zWQzmGUicxSydtwp/tsd7dubIOl4/OpegnlbZvGnC4pPyZNHkILcmjHm60buBzrvxPruSq4sfG6c2WMEBzA4hPMPBo9kmdkiM1KjHhG01OkNBFK0mrV5UhM/ykIY6Rvdv6G45EWZ2roe23pcT4f2z3rlJ9GyPDuPLSJtqSV7+NUB51j5RFxwgvRd8hmE2ZT6916aYXcCWBrpu+jDNhu7g3gOaB1uW4K4B3nnqAmHMr73oMmNMadBgq6T1aoWgvw/ULXOwSWKMLJ4BKuJZ8ZqLwLA3rX1+GDrjdxeLA==Emotional Roots of Prejudice

scapegoat theory the theory that prejudice offers an outlet for anger by providing someone to blame.

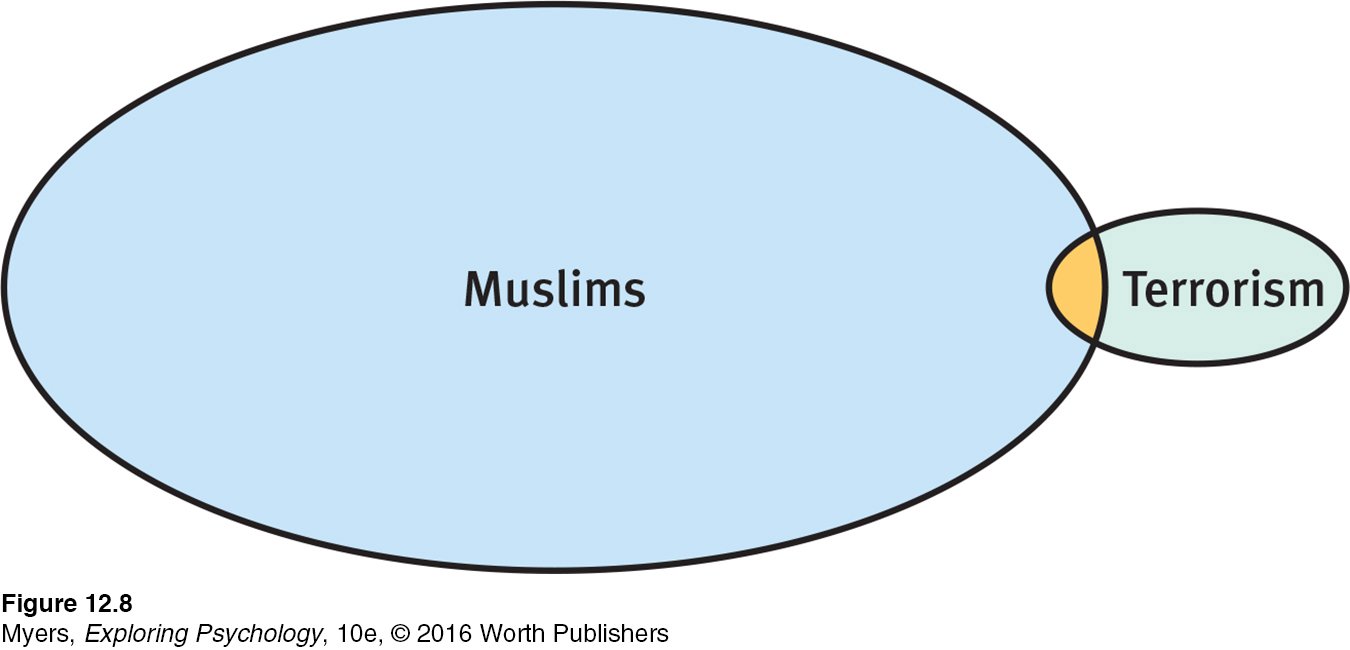

Prejudice springs not only from the divisions of society but also from the passions of the heart. Scapegoat theory notes that when things go wrong, finding someone to blame can provide a target for anger. Following the 9/11 attacks, some outraged people lashed out at innocent Arab-

“If the Tiber reaches the walls, if the Nile does not rise to the fields, if the sky doesn’t move or the Earth does, if there is famine, if there is plague, the cry is at once: ‘The Christians to the lion!’”

Tertullian, Apologeticus, 197 C.E.

Evidence for the scapegoat theory of prejudice comes from high prejudice among economically frustrated people. And it comes from experiments in which a temporary frustration intensifies prejudice. Students who experienced failure or were made to feel insecure often restored their self-

“The misfortunes of others are the taste of honey.”

Japanese saying

Negative emotions feed prejudice. When facing death, fearing threats, or experiencing frustration, people cling more tightly to their ingroup and their friends. Fears of terrorism both heighten patriotism and produce loathing and aggression toward “them”—those who threaten our world (Pyszczynski et al., 2002, 2008). The few individuals who lack fear and its associated activity in the emotion-

Cognitive Roots of Prejudice

467

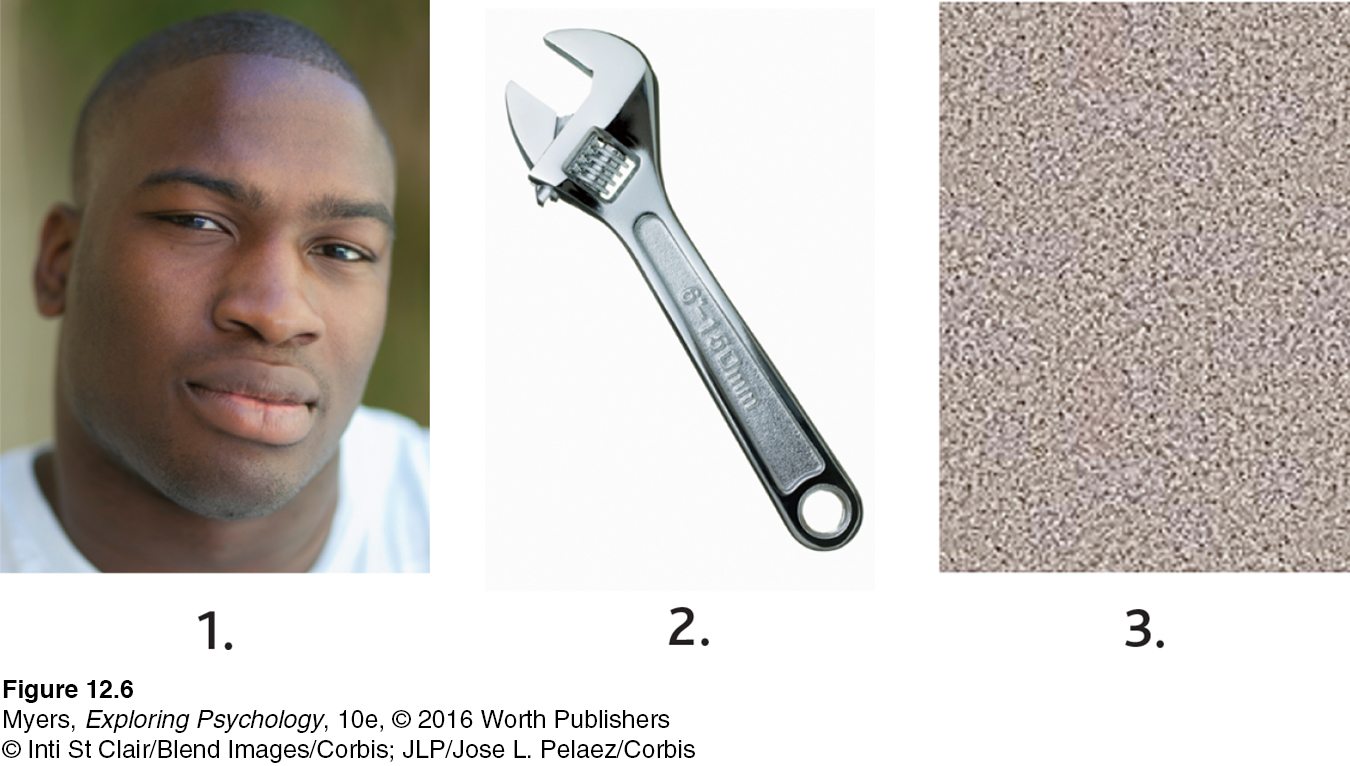

12-

Prejudice springs from a culture’s divisions, the heart’s passions, and also from the mind’s natural workings. Stereotyped beliefs are a by-

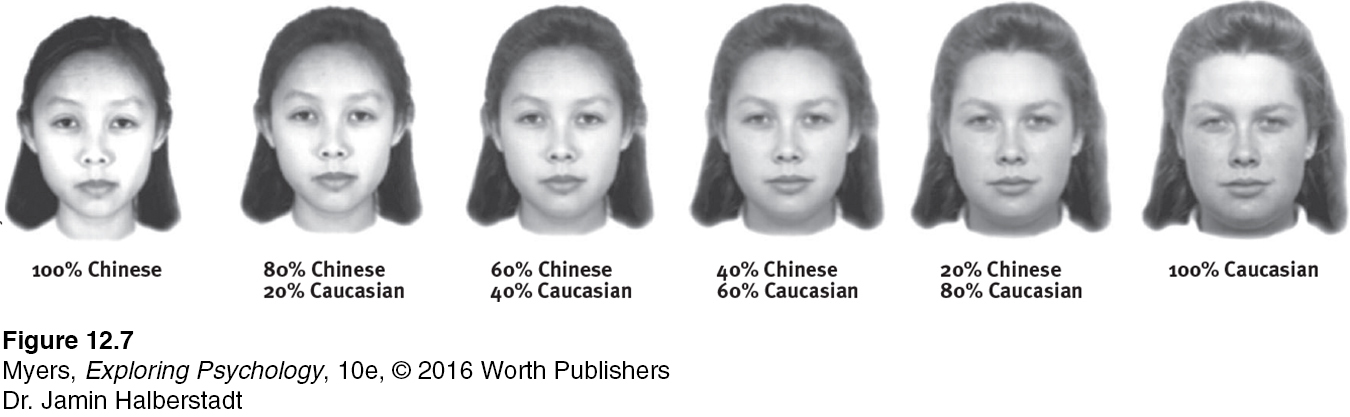

FORMING CATEGORIES One way we simplify our world is to categorize. A chemist categorizes molecules as organic and inorganic. Therapists categorize psychological disorders. All of us categorize people by race, with mixed-

other-race effect the tendency to recall faces of one’s own race more accurately than faces of other races. Also called the cross-

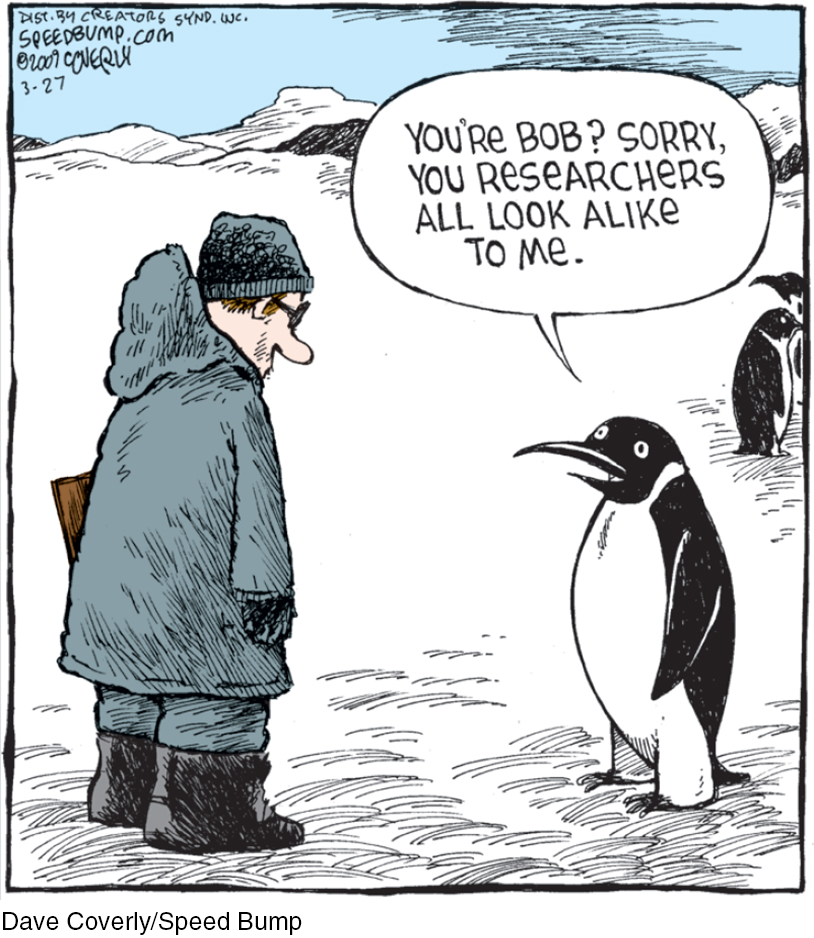

When categorizing people into groups, we often stereotype. We recognize how greatly we differ from other individuals in our groups. But we overestimate the homogeneity of other groups (we perceive outgroup homogeneity). “They”—the members of some other group—

With effort and with experience, people get better at recognizing individual faces from another group (Hugenberg et al., 2010; Young et al., 2012). People of European descent, for example, more accurately identify individual African faces if they have watched a great deal of basketball on television, exposing them to many African-

REMEMBERING VIVID CASES As we saw in Chapter 9, we often judge the frequency of events by instances that readily come to mind. In a classic experiment, researchers showed two groups of University of Oregon students lists containing information about 50 men (Rothbart et al., 1978). The first group’s list included 10 men arrested for nonviolent crimes, such as forgery. The second group’s list included 10 men arrested for violent crimes, such as assault. Later, both groups were asked how many men on their list had committed any sort of crime. The second group overestimated the number. Vivid—

468

To review attribution research and experience a simulation of how stereotypes form, see LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Not My Type. And for a 6.5-

To review attribution research and experience a simulation of how stereotypes form, see LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Not My Type. And for a 6.5-

BELIEVING THE WORLD IS JUST As we noted earlier, people often justify their prejudices by blaming victims. If the world is just, they assume, people must get what they deserve. As one German civilian is said to have remarked when visiting the Bergen-

Hindsight bias is also at work here (Carli & Leonard, 1989). Have you ever heard people say that rape victims, abused spouses, or people with AIDS got what they deserved? In some countries, such as Pakistan, rape victims have been sentenced to severe punishment for violating adultery prohibitions (Mydans, 2002). In one experiment illustrating the blame-

People also have a basic tendency to justify their culture’s social systems (Jost et al., 2009; Kay et al., 2009). We’re inclined to see the way things are as the way they ought to be. This natural conservatism makes it difficult to legislate major social changes, such as health care or climate change policies. Once such policies are in place, however, our “system justification” tends to preserve them as well.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

njjNKIrNsOrbGFWp9ceTmzlp2/Jux25SSa57yM0CosZX060ClOeYdrLWo8K0hXGoe+Y3Vs7a7VGoqVpd0+Mv5qD6K8tSXJCgVYVGWFByRVWJ+3O7zv5WV6yEz/HND2/Pj98xXrwblXZwV5gUfdX4I27hQCaWLTA8rWapu/ulfWIuL9GFwyLM2JFGtKfeCm+khMQtFIYVF8qwA0BZOwIdiA==Aggression

12-

aggression any physical or verbal behavior intended to harm someone physically or emotionally.

Prejudice hurts, but aggression sometimes hurts more. In psychology, aggression is any physical or verbal behavior intended to harm someone, whether done out of hostility or as a calculated means to an end. The assertive, persistent salesperson is not aggressive. Nor is the dentist who makes you wince with pain. But the person who passes along a vicious rumor about you, someone who bullies you in person or online, and the attacker who mugs you for your money are aggressive.

Aggressive behavior emerges from the interaction of biology and experience. For a gun to fire, the trigger must be pulled; with some people, as with hair-

The Biology of Aggression

469

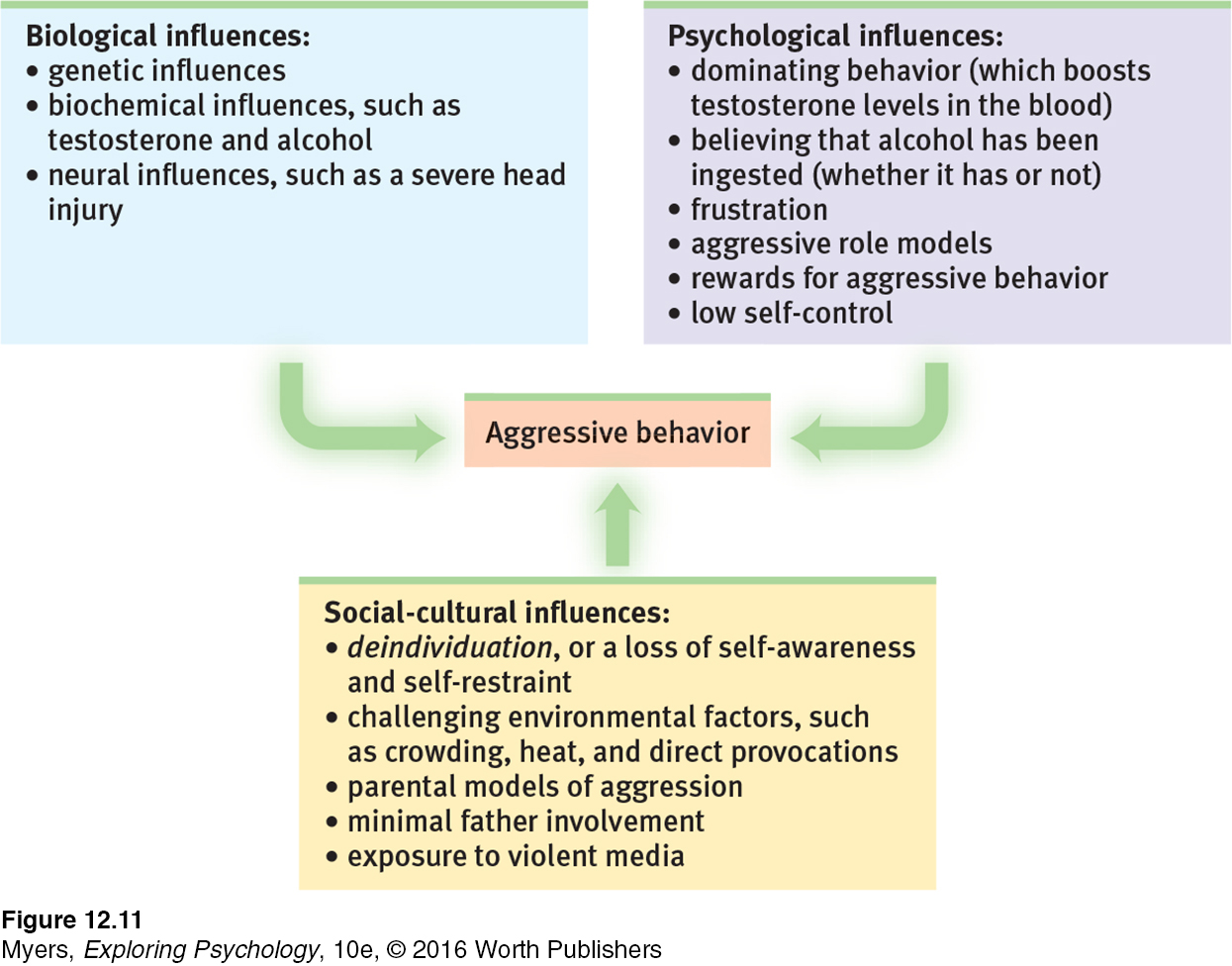

Aggression varies too widely from culture to culture, era to era, and person to person to be considered an unlearned instinct. But biology does influence aggression. We can look for biological influences at three levels—

See LaunchPad’s Video: Twin Studies below for a helpful tutorial animation.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Twin Studies below for a helpful tutorial animation.

GENETIC INFLUENCES Genes influence aggression. Animals have been bred for aggressiveness—

Researchers continue to search for genetic markers in those who commit violent acts. One is already well known and is carried by half the human race: the Y chromosome. Another such marker is the monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) gene, which helps break down neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin. Sometimes called the “warrior gene,” people who have low MAOA gene expression tend to behave aggressively when provoked. In one experiment, low (compared with high) MAOA gene carriers gave more unpleasant hot sauce to someone who provoked them (McDermott et al., 2009).

NEURAL INFLUENCES There is no one spot in the brain that controls aggression. Aggression is a complex behavior, and it occurs in particular contexts. But animal and human brains have neural systems that, given provocation, will either inhibit or facilitate aggression (Denson, 2011; Moyer, 1983; Wilkowski et al., 2011). Consider:

Researchers implanted a radio-

controlled electrode in the brain of the domineering leader of a caged monkey colony. The electrode was in an area that, when stimulated, inhibits aggression. When researchers placed the control button for the electrode in the colony’s cage, one small monkey learned to push it every time the boss became threatening. A neurosurgeon, seeking to diagnose a disorder, implanted an electrode in the amygdala of a mild-

mannered woman. Because the brain has no sensory receptors, she was unable to feel the stimulation. But at the flick of a switch she snarled, “Take my blood pressure. Take it now,” then stood up and began to strike the doctor. Studies of violent criminals have revealed diminished activity in the frontal lobes, which play an important role in controlling impulses. If the frontal lobes are damaged, inactive, disconnected, or not yet fully mature, aggression may be more likely (Amen et al., 1996; Davidson et al., 2000; Raine, 2013).

BIOCHEMICAL INFLUENCES Our genes engineer our individual nervous systems, which operate electrochemically. The hormone testosterone, for example, circulates in the bloodstream and influences the neural systems that control aggression. A raging bull becomes a gentle giant when castration reduces its testosterone level. Conversely, when injected with testosterone, gentle, castrated mice once again become aggressive.

“We could avoid two-

David T. Lykken, The Antisocial Personalities, 1995

Humans are less sensitive to hormonal changes. But as men age, their testosterone levels—

Another drug that sometimes circulates in the bloodstream—

470

Psychological and Social-Cultural Factors in Aggression

12-

Biological factors influence how easily aggression is triggered. But what psychological and social-

frustration-aggression principle the principle that frustration—

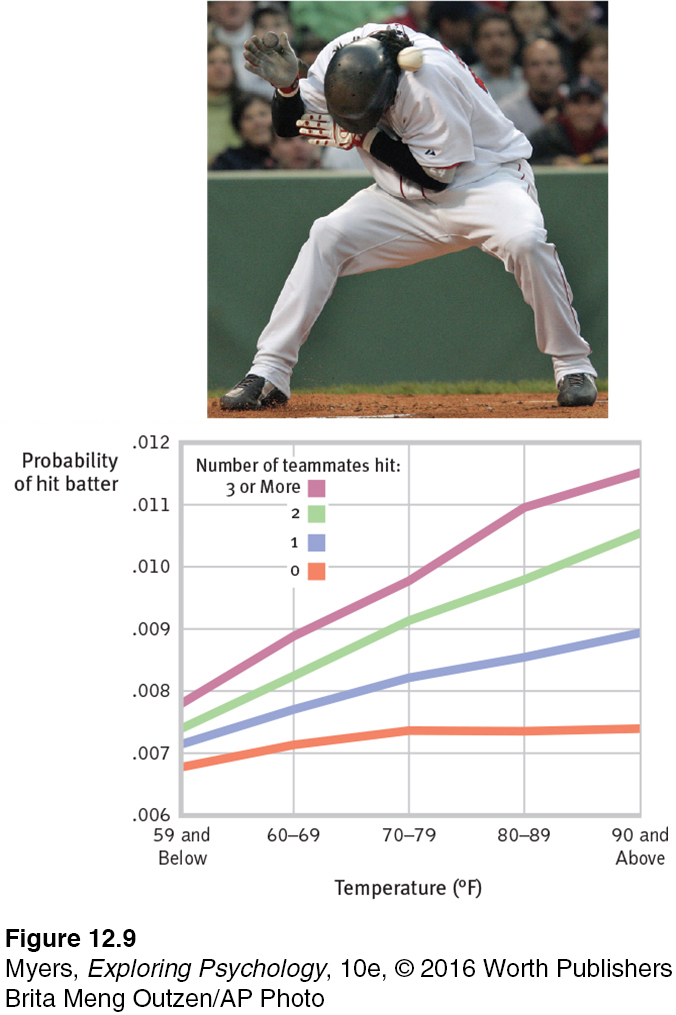

AVERSIVE EVENTS Suffering sometimes builds character. In laboratory experiments, however, those made miserable have often made others miserable (Berkowitz, 1983, 1989). This phenomenon is called the frustration-aggression principle: Frustration creates anger, which can spark aggression. One analysis of 27,667 hit-

they had been frustrated by the previous batter hitting a home run.

the current batter had hit a home run the last time at bat.

a teammate of the pitcher had been hit by a pitch in the previous half inning.

Other aversive stimuli—

471

IMMERSIVE LEARNING How have researchers studied these concepts? Learn more at LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Hot Temperatures Cause Aggression?

IMMERSIVE LEARNING How have researchers studied these concepts? Learn more at LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Hot Temperatures Cause Aggression?

REINFORCEMENT, MODELING, AND SELF-

In situations where experience has taught us that aggression pays, we are likely to act aggressively again. Children whose aggression has successfully intimidated other children may become bullies. Animals that have successfully fought to get food or mates become increasingly ferocious. To foster a kinder, gentler world we had best model and reward sensitivity and cooperation from an early age, perhaps by training parents to discipline without modeling violence. Parent-

Different cultures model, reinforce, and evoke different tendencies toward violence. For example, crime rates have also been higher and average happiness has been lower in times and places marked by a great disparity between rich and poor (Messias et al., 2011; Oishi et al., 2011; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009). In the United States, cultures and families in which fathers are minimally involved also have had high violence rates (Triandis, 1994). Even after controlling for parental education, race, income, and teen motherhood, American male youths from father-

Violence can vary by culture within a country. Richard Nisbett and Dov Cohen (1996) analyzed violence among White Americans in southern towns settled by Scots-

social script culturally modeled guide for how to act in various situations.

MEDIA MODELS FOR VIOLENCE Parents are hardly the only aggression models. In the United States and elsewhere, TV, films, video games, and the Internet offer supersized portions of violence. Repeatedly viewing on-

Music lyrics also write social scripts. In experiments, German university men who listened to woman-

Sexual scripts depicted in pornographic films can also be toxic. Repeatedly watching pornographic films, even nonviolent films, makes sexual aggression seem less serious (Harris, 1994). In one experiment, undergraduates viewed six brief, sexually explicit films each week for six weeks (Zillmann & Bryant, 1984). A control group viewed films with no sexual content during the same six-

472

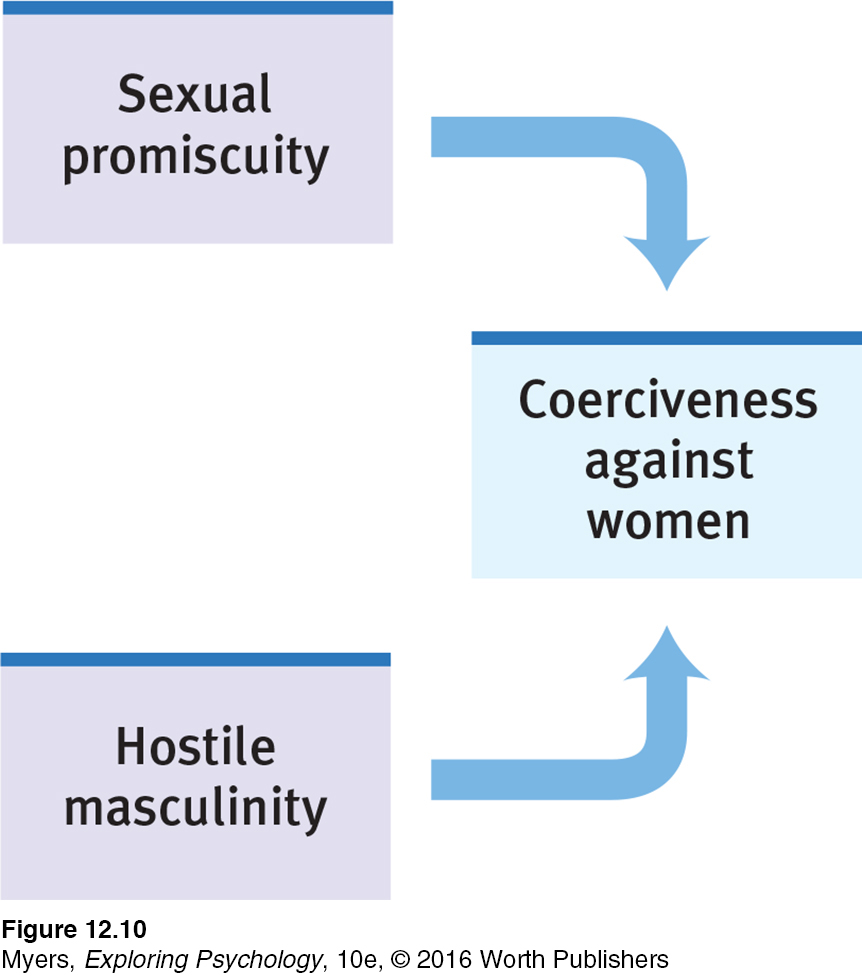

While nonviolent sexual content affects aggression-

To a lesser extent, nonviolent pornography can also influence aggression. One set of studies explored pornography’s effects on aggression toward relationship partners. The result: pornography consumption predicted both self-

DO VIOLENT VIDEO GAMES TEACH SOCIAL SCRIPTS FOR VIOLENCE? Experiments in North America, Western Europe, Singapore, and Japan indicate that playing positive games produces positive effects (Greitemeyer & Osswald, 2010, 2011; Prot et al., 2014). For example, playing Lemmings, where a goal is to help others, increases real-

In 2002, three young men in Michigan spent part of a night drinking beer and playing Grand Theft Auto III. Using simulated cars, they ran down pedestrians, then beat them with fists, leaving a bloody body behind (Kolker, 2002). These same young men then went out for a real drive. Spotting a 38-

Such violent mimicry causes some to wonder: What are the effects of actively role-

Ah, but is this merely because naturally hostile kids are drawn to such games? Apparently not. Comparisons of gamers and nongamers who scored low on hostility measures revealed a difference in the number of fights reported. Almost 4 in 10 violent-

473

Other researchers are unimpressed by such findings (Ferguson, 2013, 2014). They note that from 1996 to 2006, youth violence declined while video game sales increased, and argue that other factors—

* * *

“What sense does it make to forbid selling to a 13-

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, dissenting opinion, 2011

To sum up, research reveals biological, psychological, and social-

A happy concluding note: Historical trends suggest that the world is becoming less violent over time (Pinker, 2011). That people vary across time and place reminds us that environments differ. Yesterday’s plundering Vikings have become today’s peace-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

AJleq4TKcdcSWS/huxRAKcd4QA9voaOwtPa+Ky6h5ZUvef8y/U/dX0NP3rOTHz0JenK30rPD1VccJ2NudW305qSLmSK32tP5YM8iJjL9tNDyh+jNorLmFAzv8VmErtkD1+51Fzp1c8aAXs8Byr2Yz8KhlW7ANYmFIa53cUA5oUKK8GvjmauxHTlJRd6zfOsELpDF6htM19M2Mwu6IXuXvK01M1etuBVqFwLP8RUaSbfL7Sz1HtCs1MQbnvbhsQcE8eb/3G39J+g=REVIEW Antisocial Relations

Learning Objectives

474

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

LLRMtLHHTS0aXk0dUVrkia81XBCvhsUEHLYPZNBZFEJ1wKAoqUhf2zWGCdWVyTpp68AcOWj3JMtWPVgrgVdIN+D+AVKY0qDv7pIo/dHmHAJ1PLhOxZZBuqR8A6K1i3T8FYOagAlCzGsogdzHEfF+CqazlAGx6u3u/hxtOuqNoF2dTtyQB40fdaPtWbGSMO5FLjLuTw1Q7IT72EcHciyGaVHd+W3dmaBnFSuicHU5ZH1BUVDKWNAAmg==Question

7R2tdfJ28usswseZiSgDORNrpr/4NlqTE3kEUu8E8ExCF6c6VftOYDQlMPuweYZHSl8WwruF+YKL3kJShXaaHBaMRuruhCLeQojgCnm08zhQsC7LOfFZGqLtHGmDgvECfB8/oou307wv/LRhuxveHpBKizVK9uK96INAJ4TKw/tFuzYNHNDjFQaOS5SjmXuLOY4CQBnsMEsNgz8kXbTX/Q==Question

Q3Vad//l6NDxtpXGRqXsuMDpBY8TNx7RKeKoYzte8fe2uH3KWZgXG1taZbH8n8lWZdTgZezeP2OjHlZD2Cmoa4wWwsycfIHrY5wJo4QRL5WxsqycgyyjSoDTjhy/xutxw88X2K4YpTZ7WQXmAJdArCHmUPt2lKE/fROqUHrCjk6e0hJ0gl3MGJ0BxiDzcPZJrrMcs7LUFz6/0S0J9dcmcEAAh8a84gL9oQW8yW9TrfQexXu1zFSfa9vee7sYtujJBtvW4HDivNCik6SU1LN6CPeUGdxn8n8m4E2f7Qx27CzRyv7AhAl8dwblH0pu7rHCLdv4lucwCtxV9dmly/IkZPHU0y++KHWHQuestion

AYJzCDPtXgYrfmAq+HVb2cywCJwcvJIvbjr4Tw89JNmjNBk2yZyaH8stlI/+mwYoEn49ma2S2+/ou2eDDarfBkPlKRsbQo3lABpihHs8Up2WlDzfHCvNQl4wlVuIunfgjg7JKsk4AABqki3tyl6hlDVgOI85mi8yRKKUW0ykuNv0PQFqvtDhgltJWT9Rnnc88BHq4zu2Flblk4y6khGWQIt98tM8KChJgCv+a95pGGfVg0482gajR1zWIwbt5FgEefSwQFGpLPoEdS3ADNG23OoZ3jS4642V+oR8QACTTDO03UDZqS8ugIdiMsYqxT8Yj86YGg==Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

o8ZqDY8YdZWWHBhCREvn3ENFCqmwClrfZD/nHnYvHerVohu/Swq/V+QOI2w2Oc2yi8OGNzeVGNJj8HEILZitmxM4Z9WufAsVIYduYIHGYXqnUmvMgpJYpqJ5avK8AQH75moMMY3BllR1D9j5EBWgF9qAW7lpWHRaf8BoHjILa80Kj8mZhE3J3uUPJ13jOTUi0uc05nAgyRvjbdvCF7nf2VbKDq6qmJIA+1ty/xgwbAOvkiV72PAVeha99mA7mcSbR0fNaLawa+9jWtK4ksSfQ+RGkOfdJXz8eQlnImxKxVdh3Tlv3FB5Tiwc419n5+AOmqF9OimymB+Gt0C2qB/68X51+dB0WhS6KsisnmrgMQo2TBvb0XjEaMRIAzPv580r3qnHLb+qkrwc5GN8ci4cCglU6+kPK80OwNTUKQBzsVFONrjAbMYviCQLfE/D5CzeWtzeG+Np04vWcohh0LDiGbLjrnS7gWdaQZTo0NabU7zYKceWQLIbLGdg1b32zA2q6ajdUSUEziEWWMvL+5vNbZtU2Zcv+ZbyGbk2PgXG5ihDHJgH0WmFnGNeZJKdHi0VX2A7GcIdIf9vgx7Tv0FdQ5IkaBBS6gRijld/iL5WzrWcvx16hvBcbcR7sBqkaaMpjk6dSxgQgzKz62Fg9p/zPXaPSXlleD2nH3F7khfw/peZRgcV/G7ZpX38mX6yGfoHamGbmt2In6+wwkMv2FupFaDYZXUQV2Sd5u1XCPl1ZTy3MSJcnWhKVRmJQV+NDx3Wd6eiDuPCueF7WZ1/P402wwGWLNz8ql6yQIN1raeiXF8lTQxlQ4p/7NmIJa+ycogxT4ibCvXseGR5SEWtSk1xqPuDa54qFl6cAU1Tx7Q/Ns6zg29aCFNCirtLL813ewu8XOhK0QUlDbzos0UmjjY+uiJf1ke4VF4kr8gz5LzlMRQ478qa0i1j+pTVWmCModGCnlRIMpKwiVlrYQrVZZnmlWDI+lnAzGjUcYGR58tgzGvhcmgZdisasj0FpGHr24VsW+55F3oRL0PcpxeBxmQIVlutFALnNTe2HFyuSbsqDoPRZsWQtVkLST47NykQ7NdokjU6zjcG/xaweXyGSkvmBovSs5Ws1TY2rOPCX8eDZMtrokxXmFZIkpXDEzLW/g9Cqw9iREnMrRFpyIZplfs57VVprmLKLqf1QXJMZZm9vmM6EYXl8WY1Fh04EYAe41LgzlvBo8EWd1YbGD3WqB0qV/rgppQv/pAVcECrzMaWjwSwbpd0v5EKPVxiAZuCZ36ylW/HKg5awfg1PHWqbh5hLLbWxZG4zwaJyOb3p7sk4iaXnUzD20+TZRHl6wMqD5co4cPItdEKIN+fkcwgeediKqgbW0yzaL3uoyFH+CnN2KrpgV/JfJf28hGmBJ4AhdwJXEqVkO5dgfOxAdJDo7LZvZoRtw3AY4xqJJseqUxxcelG7FvFRUb/R9pOCVMlHkGnlZHb5W/PjZeC6ljx2sDH3snhgtiVgtAp4yULteB131xaecgJEd+bu2wmj0h9WlcvQnJFUYrFual8VZnMGAuGnfwqb0lPXzAIV9ZqNjrJD7NaMevYGJ1ZEt02PuLNx0GUVAjnXONfYjC97Bbuv8ayLHzSBitI+OiitUOe0wy3PM3SSjtjtGBUlrvdKf+PCNxbpf5Hj66n/q/b8GYZvM0qXKtKug6dQoyFRy+8Z+fBoKkkcsjT3lPURFdJ0jirNUAvo0cUc1aF5W5oNvMCKnNXog3i47ihkeYsNTDaw4GGn98Imveed3fMLKI6aSuxFyWG+CGPmCC4wrNd4cn0mi8QGO3pdPrbc9Ke6A/gK6qSCMZRQhzIHOvEjn4ged58AE+pMC+s6LuqDN6e6deCLwjfuY/LkcPPhDwNuCI7PgY4pgn6R/zs0Eqy4yr7xmsbj1wExSZ76o48sleQ34CzSFhSYyrvxIDbuKm28vUdxvZPX2Nx/v26SB15zhYDhrYgpNLL3hqQTkPgPhFeOK3O00jJ2i7dMomA3Qd4WQVWWdm7NDf37YwevnbRqORfD6yK1xqbisKGbIXXBerrKT4xwVLCJw+ru/sQjnHnbLUNTSLDC3MkUDqLb8gk/yi96ytrUcyXo05uICguInFH0LeMVtyw3mWcJw+fSk73GXO9PykUzXwuUspzdbQ8GSAym/VRM0I0z21JigFADJyhGV8Wrt0y1CAhzL7A2HistO+eeipCIh1ExC0A8/j8ZtdZEBwlYdnh9BYgQW6eSf+9PFaZoB6um1TmluoDGQjL8aq9aO1emG3Gha1663qobkujzNDEwXDjWBoN2rzGuo70j/v6zqXMsIqtZ0VBpkywZKupm6UQbaChy26rdZIC44QLxPi1obbUGhjEgNHvGzGu9Nw4Z2PCE3lnJEeLVPetGTSwW7pyn9po4gpA7TT9G8WJZ37WkL86uU1zoq9KPU3DXaZEExperience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 12.10

1. Prejudice toward a group involves negative feelings, a tendency to discriminate, and overly generalized beliefs referred to as RXBGnDHeNByxpkV6hoYTpQ== .

Question 12.11

eTBM8yWh2XL0QGHCVOVdcQritPdnV+GIsWKRooEwmooIgEOWFvc1nNaW0LAajIyCUptW5XJGC4uXvtGnJ4ZM2MN4TjdiXa18YvoMe0D7/grZispEvCN+sL+tkrtmFAdTM7doHphKBlCseaFMMQqzQ5w4IwA3d7kDuqrojnIh3JqEcLH4dvo+pq21MqHm2d2A0yofwOnWO+98MAqHVI9p3uuSt9voD0L99i55M7lN+fX5JYj8xC1CkPaufHHC8wVDWNkDdYU2xsZEctJeK8yp8c1ykr9JILR7S1VwAnPo8+Ha8PtuU+XCTaQhj/v2l0StMq5hBSvWh+6ArcnPbRoy/QF2a2eVJTYaNv+QMIPBd2KD9cKP5fK+alm4kP8tDtVfYL/Qf9wwx2qOPVn2BYFNOCwxnionU0EK8cwZdw==Question 12.12

3. The other-race effect occurs when we assume that other groups are w4/XmpGVUtcmSod7 (more/less) homogeneous than our own group.

Question 12.13

Q/tjELvzO+gRbwWrTiEHWsqssKUeAKMvWQD7fNm9/Vzk5230qBQAUeW35eepRYbb6bpFkopl6Gcdi+qTZHAa/bhxR0Im3rc52J4xrN83NOXV2nagJbuvtjCf/mmhdS9u/pS0eyDjnLh6ayAyFpWOzM/cijK0qoXZWHy3VS5MyeevFKm/qFWQ9p+yCeRjDpLbJ+2dx+eIXDF41BAqI7V9NmbJqs/hpxmSv2KwJoIyiHIdntU4laJWGrFgJspG4FabCG/ON8NkMqMcBb7yPrITv7xJpHI3OnXfgPQ+qAC6dW0XEeARkaTva9wxqGkse24RnqrecJAKmE4boXGvOXIUgumWd11yS57SqKy3V++DZYB+Kl1I1wGZixyD5nSmKU7RGiMs2WIGmWCyv+k+HNlxzHxQMXzDE6+vmh7SELdgo+wZG1i04tnMMTkjhA5z/vcc9lcAVFqQ33c3F+30Iy0C2ldTfCqBsfEYq4tg/Q36zxZX+lranIstjjLS4aXGTFKaJkyQok7d4U/igOWllDe/KCjJKuW7cfYSuV5r8Cl5Tso=Question 12.14

5. When those who feel frustrated become angry and aggressive, this is referred to as the nycBm388NFXfQxSKLIm1/WDKdmVPSdJeFBkDZCOrcVjkGJndjcAjkg== .

Question 12.15

DEz4Uxx1dK8MeWGlxd4hihrESpxBFJ0xeJd19fwVfJ1TxEzhqtXgwPMNKb9IshoMIBqF8jIHYIsESE/Vj2xg/rZnGjethAfmmkFyeoNPA/C5mGjpin4hB8hpegneD0FXZ/h/Hb5Q/cwPNxD2NBqVi+69JVv1uLlMisSFgWIxj6FTqwsUF+E8c9IYr0Ukz/tkIB/DCuZaeR+IgxcpYsV/83/OVlBJJ77kf31qZx2eo47O+vjeNQSjqQgnPpxxJ+ty7TzZywJ91O5O8xlfdcJ/QgqbW2xlTi8CBU8VRAbs6ttsu6PeArq+6okSFBjbCN7IAbe6deM0CfNeMUUAjth/HNZRLLYwNnv7PK35+pQ9471Gm+Q5BZSXxlrw2TTtgEc/l5s1MEyod0mBBS8ZXMX0wqMvU3x9dV03NNJQb5ygbCbSlfUex3CtmZi11HRk7cpjVQDVKe9syyN5quRf69gSjwD9sTjZ/ettQuestion 12.16

86Hkp72rYR8UAUli0fm0FwxquurEFFYdm/woIhzrEBg12atJpQlTHtZsCQ1w2elN2A7etJmlQzD7BYQWIYS1K2ZHGCNo23vDlMdlWe2nGlGIeOBg4u59KLEp5OWHhXJ5R/H9paysMM+5G9GVcCIPHz6M2XPvm1tH51bZYZWAn5RzZuAPPcDsR6g+N8K4s08QeanTrC77BlZ1FtuAzQDBOwdlYRmMcSCVZZPSiITcOjw1kYeFOiMd0eRtjaq4vsxcDSdeifJbufTT8l1iIQ3KIwH6vx1IV7apHpWQdUs4k/1aO/agjNK0PLjKXlzv4J+bv23d9YlvTV+b4CF8j14w++TEK8OhEhHmC/kntmvWFup5hvgQusc7lJFBwiRFyPM8uIPcj8UAPcwszV5aIuWqCSXMRQcTQTTwimZ6/CavmOJ1vuxclzv9tv2Y0Deko+maxnNNU+Fgp2B7AvWSXRBFvhArBRfAUIRHFZj+HGVornsKMjGy/Vpi6vSgyTdOxYqoUse  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.