13.2 Contemporary Perspectives on Personality

Trait Theories

13-

trait a characteristic pattern of behavior or a disposition to feel and act, as assessed by self-

Rather than focusing on unconscious forces and thwarted growth opportunities, some researchers attempt to define personality in terms of stable and enduring behavior patterns, such as Lady Gaga’s openness to new experiences and her self-

Exploring Traits

506

Classifying people as one or another distinct personality type fails to capture their full individuality. We are each a unique complex of multiple traits. So how else could we describe our personalities? We might describe an apple by placing it along several trait dimensions—

What trait dimensions describe personality? If you had an upcoming blind date, what personality traits might give you an accurate sense of the person? Allport and his associate H. S. Odbert (1936) counted all the words in an unabridged dictionary with which one could describe people. There were almost 18,000! How, then, could psychologists condense the list to a manageable number of basic traits?

FACTOR ANALYSIS One technique is factor analysis, a statistical procedure that has been used to identify clusters (factors) of test items that tap basic components of a trait, such as intelligence (spatial ability or verbal skill). Imagine that people who describe themselves as outgoing also tend to say that they like excitement and practical jokes and dislike quiet reading. Such a statistically correlated cluster of behaviors reflects a basic factor, or trait—

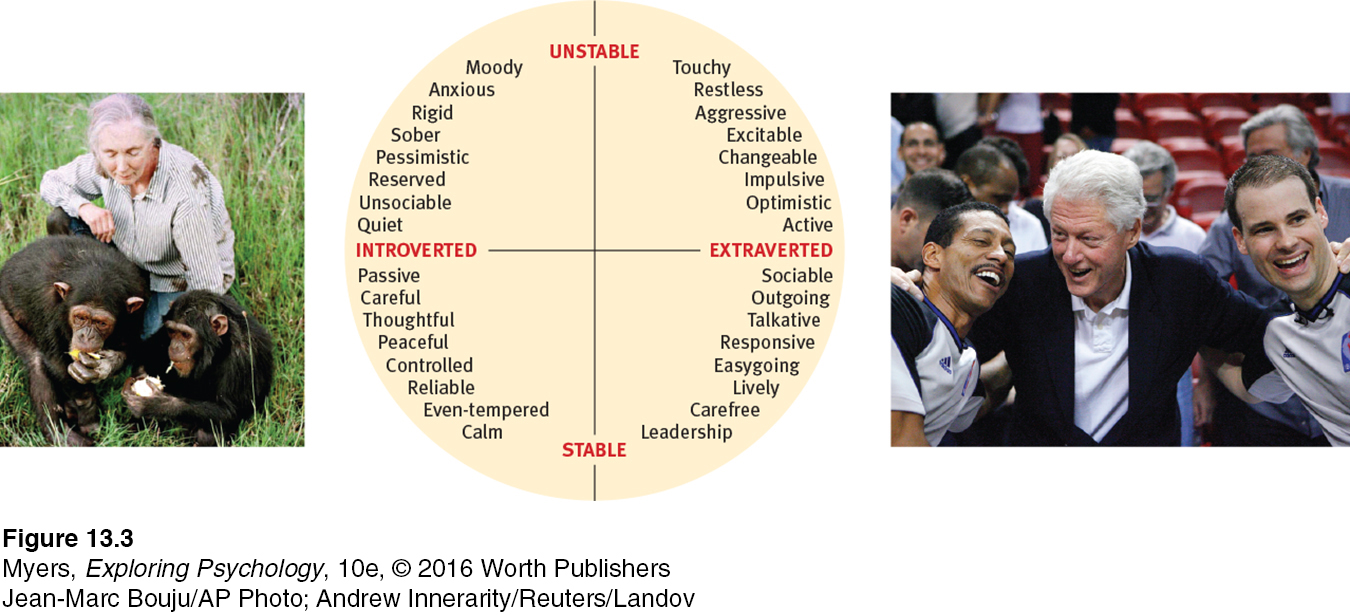

British psychologists Hans Eysenck and Sybil Eysenck [EYE-

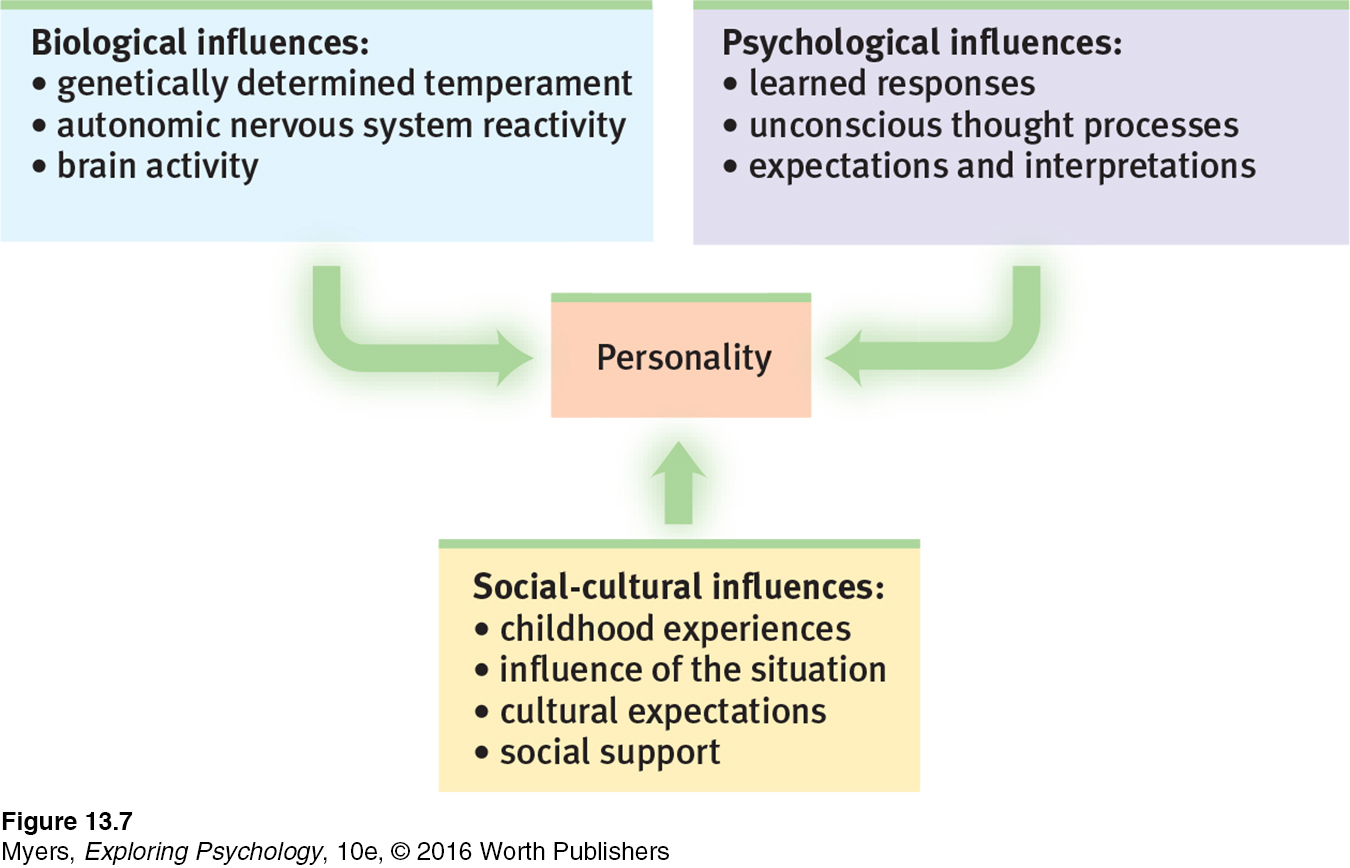

BIOLOGY AND PERSONALITY Brain-

507

Our biology influences our personality in other ways as well. As you may recall from the twin and adoption studies in Chapter 2, our genes have much to say about the temperament and behavioral style that help define our personality. Children’s shyness and inhibition may differ as an aspect of autonomic nervous system reactivity: Those with a reactive autonomic nervous system respond to stress with greater anxiety and inhibition (Kagan, 2010) (see Thinking Critically About: The Stigma of Introversion). The fearless, curious child may become the rock-

Personality differences among dogs (in energy, affection, reactivity, and curious intelligence) are as evident, and as consistently judged, as personality differences among humans (Gosling et al., 2003; Jones & Gosling, 2005). Monkeys, chimpanzees, orangutans, and even birds also have stable personalities (Weiss et al., 2006). Among the Great Tit (a European relative of the American chickadee), bold birds more quickly inspect new objects and explore trees (Groothuis & Carere, 2005; Verbeek et al., 1994). By selective breeding, researchers can produce bold or shy birds. Both have their place in natural history: In lean years, bold birds are more likely to find food; in abundant years, shy birds feed with less risk.

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

The Stigma of Introversion

13-

Psychologists describe and measure personality, but they don’t advise which traits people should have. Society does this. Western cultures, for example, prize extraversion. In one study, 87 percent of people wanted to be more extraverted (Hudson & Roberts, 2014). Being introverted seems to imply that you don’t have the “right stuff” (Cain, 2012).

Just look at our superheroes. Extraverted Superman is bold and energetic. His introverted alter ego, Clark Kent, is mild-

TV shows also portray heartthrobs and examples of success as extraverts. Many consider Don Draper, the highly successful, attractive advertising executive in the show Mad Men to be a classic extravert. He is dominant and charismatic. Women clamor for his attention. His quiet secretary, Peggy Olson, gains respect and career advancement as the series progresses and she becomes more outspoken. Here again, extraversion equals success.

Why do we celebrate extraversion and belittle introversion? Many people may not understand what introversion really is. Introversion is not shyness. Introverted people seek low levels of stimulation from their environment because they’re sensitive. One classic study suggested that introverted people even have greater taste sensitivity. When given lemon juice, introverted people salivated more than extraverted people (Corcoran, 1964). Shy people, in contrast, remain quiet because they fear others will evaluate them negatively.

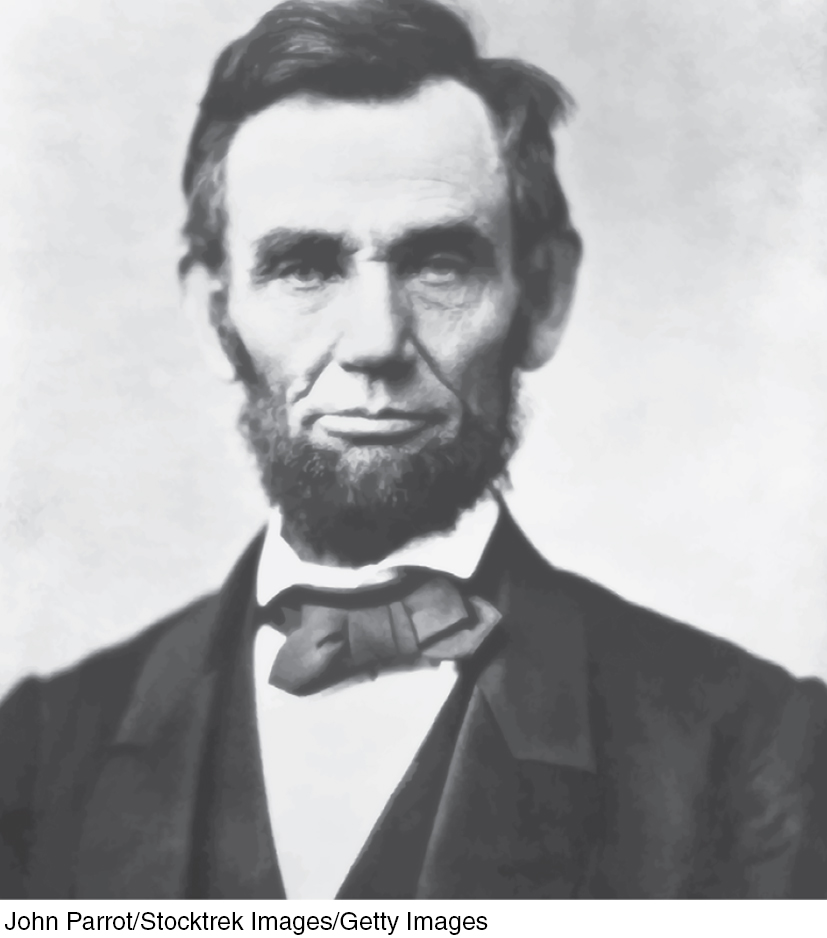

We also tend to believe that introversion acts as a barrier to success, yet introversion actually has many benefits. As supervisors, introverts show greater receptiveness when their employees voice their ideas, challenge existing norms, and take charge. Under these circumstances, introverted leaders outperform extraverted ones (Grant et al., 2011). One striking analysis of 35 studies showed no correlation between extraversion and sales performance (Barrick et al., 2001). Many introverts prosper. Consider the American presidency, which may offer the best example of the misperception that introversion hinders career success. The top-

So, introversion should not be considered a sign of weakness. Those who need a quiet break from a loud party are not social rejects nor are they incapable of great things. They simply need a less stimulating environment in order to thrive. It’s important for extraverts to understand that not everyone feels driven by high levels of stimulation. It’s not a crime to unwind.

508

RETRIEVE IT

Question

9yS2dJ1/tnp7jeU1BXqUIehJS2YOD5HPtjw9cQebCm453zefL2hp0tPsUDilIA1XTICtCMhXRNlMWqiG1aGLedSUk2p1F3fNTEn86v7B1qNu0fBhT5fUDvIU6Y8DIPk3ZHjpF+f6w/jJP4kUtfzpbh0mmNyemY4H6a1F8w+Dvq0UvkmYQ3f++hd+5oP3qT7caD8jm8R284F4fmghAssessing Traits

13-

personality inventory a questionnaire (often with true-

If stable and enduring traits guide our actions, can we devise valid and reliable tests of them? Several trait-

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Might astrology hold the secret to our personality traits? To consider this question, visit LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Astrologers Can Describe People’s Personality?

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Might astrology hold the secret to our personality traits? To consider this question, visit LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Astrologers Can Describe People’s Personality?

People have had fun spoofing the MMPI with their own mock items: “Weeping brings tears to my eyes,” “Frantic screams make me nervous,” and “I stay in the bathtub until I look like a raisin” (Frankel et al., 1983).

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) the most widely researched and clinically used of all personality tests. Originally developed to identify emotional disorders (still considered its most appropriate use), this test is now used for many other screening purposes.

empirically derived test a test (such as the MMPI) developed by testing a pool of items and then selecting those that discriminate between groups.

The classic personality inventory is the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI). Although the MMPI was originally developed to identify emotional disorders, it also assesses people’s personality traits. One of its creators, Starke Hathaway (1960), compared his effort with that of Alfred Binet. Binet, as you may recall from Chapter 9, developed the first intelligence test by selecting items that identified children who would probably have trouble progressing normally in French schools. Like Binet’s items, the MMPI items were empirically derived: From a large pool of items, Hathaway and his colleagues selected those on which particular diagnostic groups differed. “Nothing in the newspaper interests me except the comics” may seem senseless, but it just so happened that depressed people were more likely to answer True. The researchers grouped the questions into 10 clinical scales, including scales that assess depressive tendencies, masculinity–

Whereas most projective tests are scored subjectively, personality inventories are scored objectively. (Software can administer and score these tests, and can also provide descriptions of people who previously responded similarly.) Objectivity does not, however, guarantee validity. Individuals taking the MMPI for employment purposes can give socially desirable answers to create a good impression. But in so doing they may also score high on a lie scale that assesses faking (as when people respond False to a universally true statement, such as “I get angry sometimes”). The objectivity of the MMPI has contributed to its popularity and to its translation into more than 100 languages.

The Big Five Factors

13-

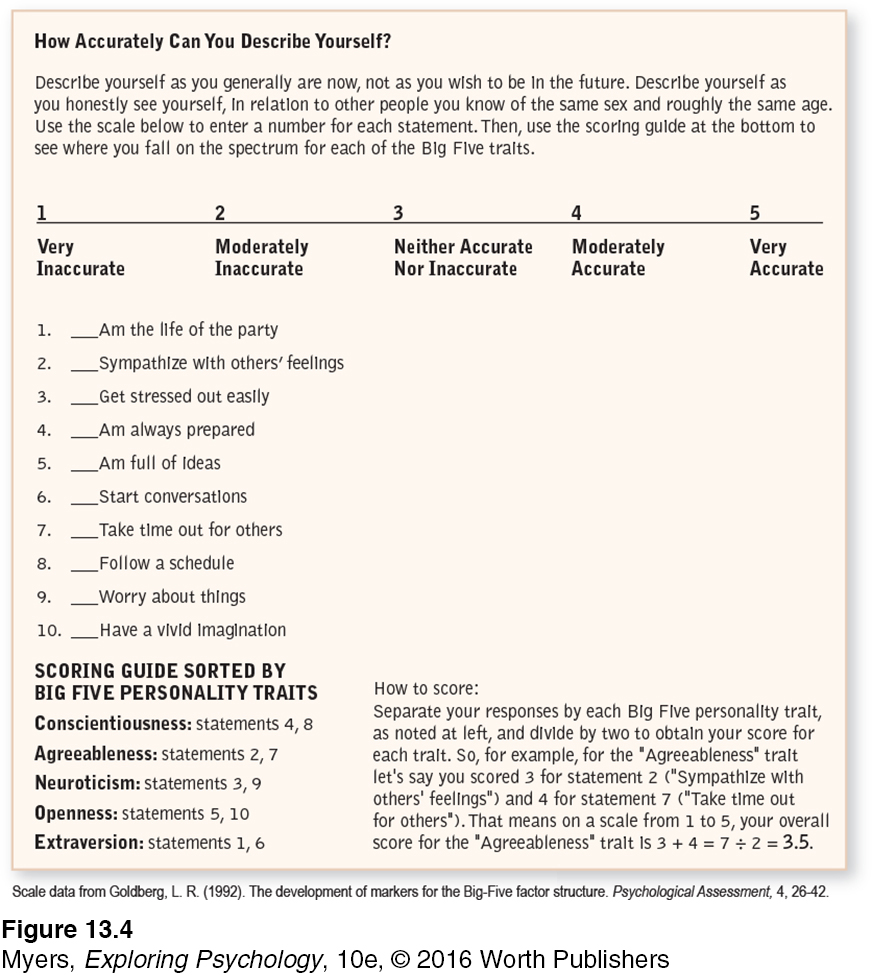

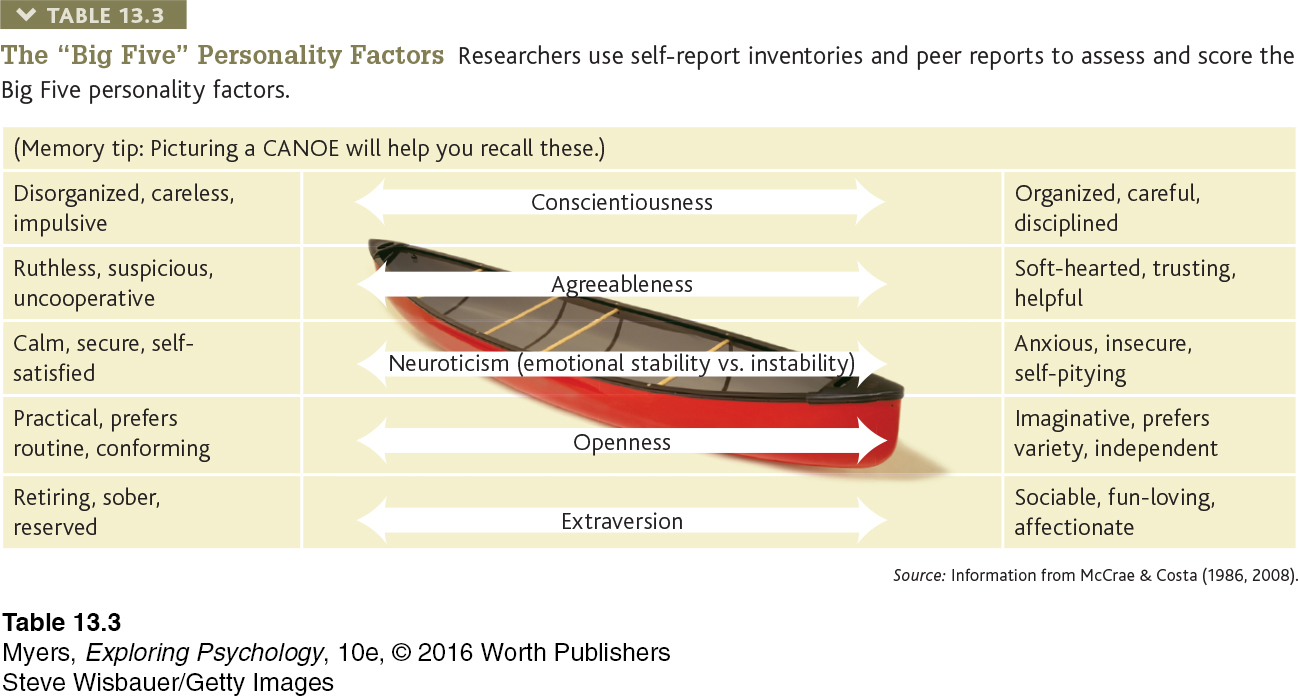

Today’s trait researchers believe that simple trait factors, such as the Eysencks’ introversion–

509

The Big Five is currently our best approximation of the basic trait dimensions. This “common currency for personality psychology” (Funder, 2001) has been the most active personality research topic since the early 1990s, as researchers have explored these questions and more:

510

How stable are the Big Five traits? One research team analyzed 1.25 million participants ages 10 to 65. They learned that personality continues to develop and change through late childhood and adolescence. Up to age 40, we show signs of a maturity principle: We become more conscientious and agreeable and less neurotic (emotionally unstable) (Bleidorn, 2015; Roberts et al., 2008). Great apes show similar personality maturation (Weiss & King, 2015). After age 40, our traits stabilize.

How heritable are these traits? Heritability (the extent to which individual differences are attributable to genes) generally runs about 40 percent for each dimension (Vukasovi´c & Bratko, 2015). Many genes, each having small effects, combine to influence our traits (McCrae et al., 2010).

How do these traits reflect differing brain structure? The size of different brain regions correlates with several Big Five traits (DeYoung et al., 2010; Grodin & White, 2015). For example, those who score high on conscientiousness tend to have a larger frontal lobe area that aids in planning and controlling behavior. Brain connections also influence the Big Five traits (Adelstein et al., 2011). People high in openness have brains that are wired to experience intense imagination, curiosity, and fantasy.

Have levels of these traits changed over time? Cultures change over time, which can influence shifts in personality. Within the United States and the Netherlands, extraversion and conscientiousness have increased (Mroczek & Spiro, 2003; Smits et al., 2011; Twenge, 2001).

How well do these traits apply to various cultures? The Big Five dimensions describe personality in various cultures reasonably well (Schmitt et al., 2007; Vazsonyi et al., 2015; Yamagata et al., 2006). “Features of personality traits are common to all human groups,” concluded Robert McCrae and 79 co-

researchers (2005) from their 50- culture study. Do the Big Five traits predict our actual behaviors? Yes. If people report being outgoing, conscientious, and agreeable, “they probably are telling the truth,” reports McCrae (2011). For example, our traits appear in our language patterns. In text messaging, extraversion predicts use of personal pronouns. Agreeableness predicts positive-

emotion words. Neuroticism (emotional instability) predicts negative- emotion words (Holtgraves, 2011). (In the next section, we will see that situations matter, too.)

For an 8-

For an 8-

By exploring such questions, Big Five research has sustained trait psychology and renewed appreciation for the importance of personality. Traits matter.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

AD2Cg7tCYXE4KXoz8xYFyf83m/m3kYg59gWOoOWc2uT33EDMeZAhFhU/PSzVeLKjeWeo5EJGvDyk6m/z0H9MBwPUMy1RBIs12cGM1X0tb0zEYcv7qZ8e+tBuDTro3Bg2Yv/uqT6Qv3gJs1G7c6LBZzwRUFoYcfHgO7viiutt76I=Evaluating Trait Theories

13-

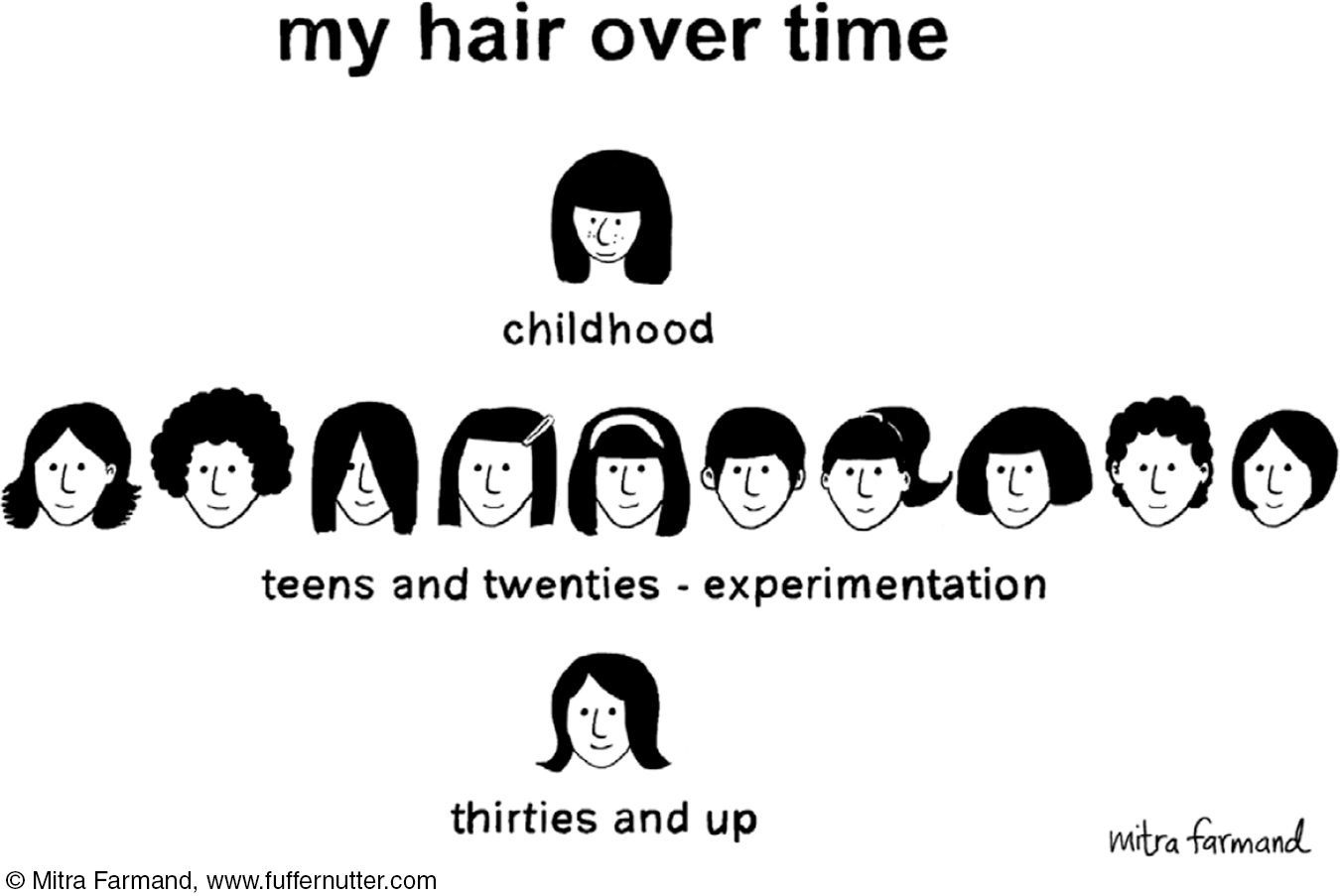

Are our personality traits stable and enduring? Or does our behavior depend on where and with whom we find ourselves? In some ways, our personality seems stable. Cheerful, friendly children tend to become cheerful, friendly adults. At a recent college reunion, I [DM] was amazed to find that my jovial former classmates were still jovial, the shy ones still shy, the happy-

511

“There is as much difference between us and ourselves, as between us and others.”

Michel de Montaigne, Essays, 1588

THE PERSON-

Roughly speaking, the temporary, external influences on behavior are the focus of social psychology, and the enduring, inner influences are the focus of personality psychology. In actuality, behavior always depends on the interaction of persons with situations.

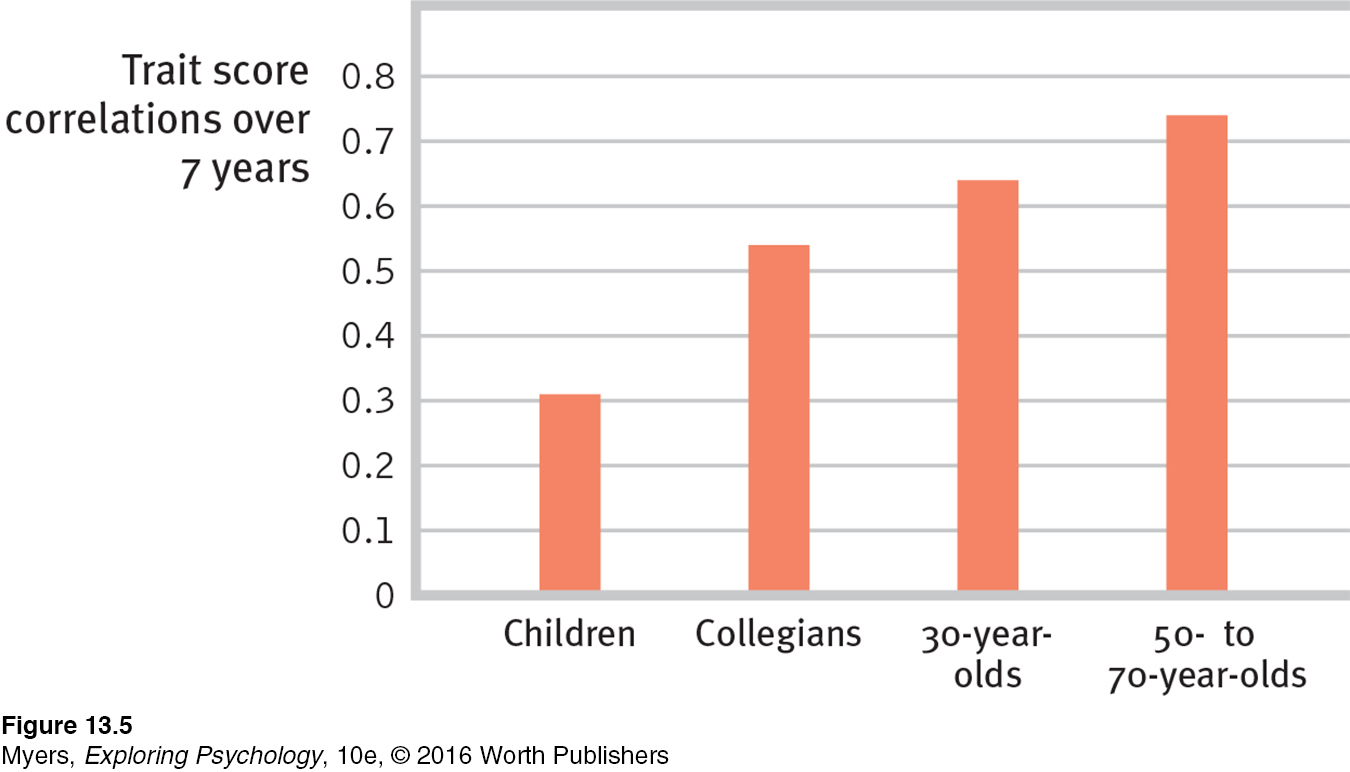

In considering research that has followed lives through time, some scholars (especially those who study infants) are impressed with personality change; others are struck by personality stability during adulthood. As FIGURE 13.5 illustrates, data from 152 long-

Change and consistency can co-

So most people—

Any of these tendencies, taken to an extreme, become maladaptive. Agreeableness ranges from cynical combativeness at its low extreme to gullible subservience at its high extreme. Conscientiousness ranges from irresponsible negligence to workaholic perfectionism (Widiger & Costa, 2012).

Although our personality traits may be both stable and potent, the consistency of our specific behaviors from one situation to the next is another matter. As Walter Mischel (1968, 2009) has pointed out, people do not act with predictable consistency. Mischel’s studies of college students’ conscientiousness revealed only a modest relationship between a student’s being conscientious on one occasion (say, showing up for class on time) and being similarly conscientious on another occasion (say, turning in assignments on time). If you’ve noticed how outgoing you are in some situations and how reserved you are in others, perhaps you’re not surprised.

512

This inconsistency in behaviors also makes personality test scores weak predictors of behaviors. People’s scores on an extraversion test, for example, do not neatly predict how sociable they actually will be on any given occasion. If we remember this, says Mischel, we will be more cautious about labeling and pigeonholing individuals. Years in advance, science can tell us the phase of the Moon for any given date. A day in advance, meteorologists can often predict the weather. But we are much further from being able to predict how you will feel and act tomorrow.

However, people’s average outgoingness, happiness, or carelessness over many situations is predictable (Epstein, 1983a,b). People who know someone well, therefore, generally agree when rating that person’s shyness or agreeableness (Jackson et al., 2015; Kenrick & Funder, 1988). The predictability of average behavior across many situations was again confirmed when researchers collected snippets of people’s daily experience via body-

music preferences. Your playlist says a lot about your personality. Classical, jazz, blues, and folk music lovers tend to be open to experience and verbally intelligent. Extraverts tend to prefer upbeat and energetic music. Country, pop, and religious music lovers tend to be cheerful, outgoing, and conscientious (Langmeyer et al., 2012; Rentfrow & Gosling, 2003, 2006).

online spaces. Is a personal website, social media profile, online avatar, or instant messaging account also a canvas for self-

expression? Or is it an opportunity for people to present themselves in false or misleading ways? It’s more the former (Back et al., 2010; Fong & Mar, 2015; Gosling et al., 2007). Viewers quickly gain important clues to the creator’s extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness to experience. written communications. If you have ever felt you could detect others’ personality from their writing voice, you are right!! (What a cool, exciting finding!!! . . . if you know what we’re saying.) People’s ratings of others’ personality based solely on their e-

mails, blogs, and Facebook posts correlate with actual personality scores on measures such as extraversion and neuroticism (Park et al., 2015; Pennebaker, 2011; Yarkoni, 2010). Extraverts, for example, use more adjectives.

In unfamiliar, formal situations—

To sum up, we can say that at any moment the immediate situation powerfully influences a person’s behavior. Social psychologists have learned that this is especially so when a “strong situation” makes clear demands (Cooper & Withey, 2009). We can better predict drivers’ behavior at traffic lights from knowing the color of the lights than from knowing the drivers’ personalities. Averaging our behavior across many occasions does, however, reveal distinct personality traits. Traits exist. We differ. And our differences matter.

513

RETRIEVE IT

Question

J7jum2GtywAhRKqVLHRpO8RFfjhalLj+Dhb8B8xp5G/p0ywQlNvBWOBZBK5KDNPHMCsiVQFLimVn400B2rJC7ntAwt8cW/BLUUXWwU9YWEymmyqvKn+wbXffPP0FmZ7ZUIFheZ2tu/ODDfNTkzAbrw==Social-

13-

social-cognitive perspective views behavior as influenced by the interaction between people’s traits (including their thinking) and their social context.

The social-cognitive perspective on personality, proposed by Albert Bandura (1986, 2006, 2008), emphasizes the interaction of our traits with our situations. Much as nature and nurture always work together, so do individuals and their situations.

Social-

Reciprocal Influences

reciprocal determinism the interacting influences of behavior, internal cognition, and environment.

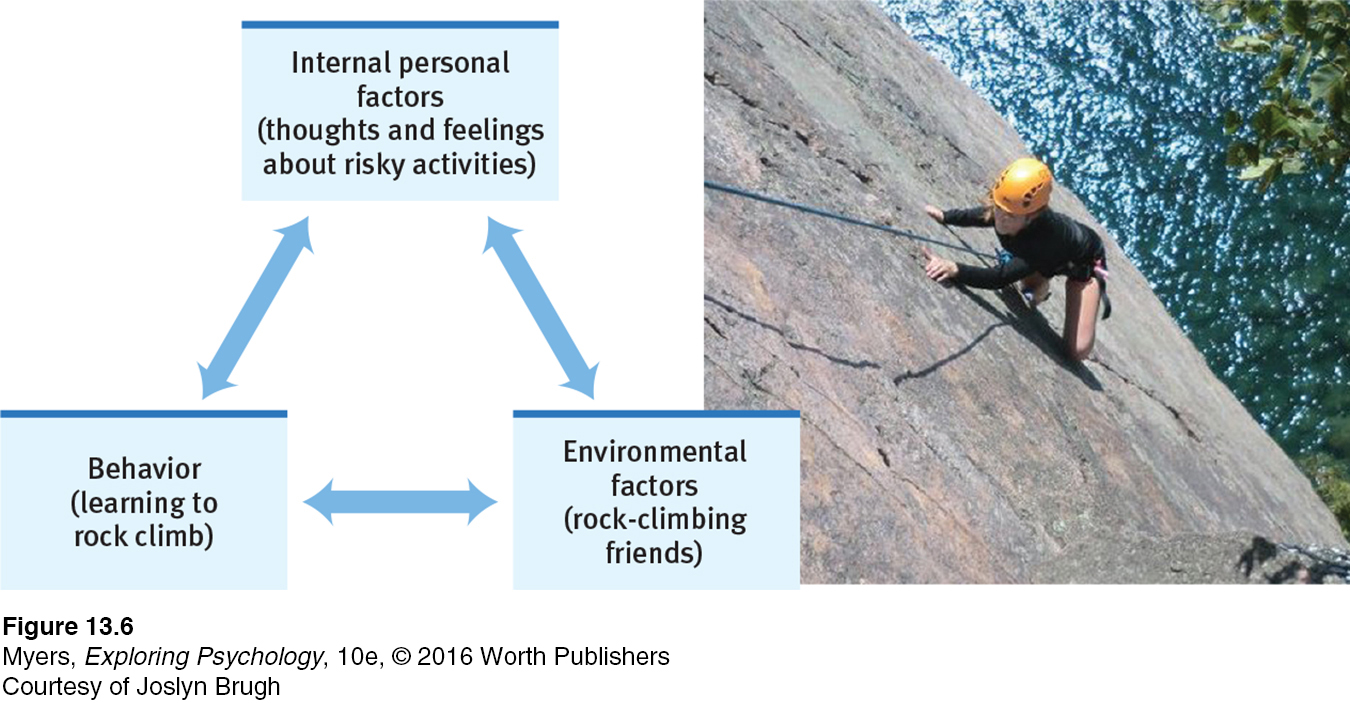

Bandura (1986, 2006) views the person-

Consider three specific ways in which individuals and environments interact:

Different people choose different environments. The schools we attend, the reading we do, the movies we watch, the music we listen to, the friends we associate with—

all are part of an environment we have chosen, based partly on our dispositions (Funder, 2009; Ickes et al., 1997). We choose our environment and it then shapes us. Our personalities shape how we interpret and react to events. Anxious people tend to attend and react strongly to relationship threats (Campbell & Marshall, 2011). If we perceive the world as threatening, we will watch for threats and be prepared to defend ourselves.

Our personalities help create situations to which we react. How we view and treat people influences how they then treat us. If we expect that others will not like us, our desperate attempts to seek their approval might cause them to reject us. Depressed people often engage in this excessive reassurance seeking, which may confirm their negative self-

views (Coyne, 1976a,b).

514

In addition to the interaction of internal personal factors, the environment, and our behaviors, we also experience gene-

In such ways, we are both the products and the architects of our environments: Behavior emerges from the interplay of external and internal influences. Boiling water turns an egg hard and a potato soft. A threatening environment turns one person into a hero, another into a scoundrel. Extraverts enjoy greater well-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Albert Bandura proposed the kcxsDC5VTGkSiECZ - XkPMXfT7QJJq66nMlxyQ1A== perspective on personality, which emphasizes the interaction of people with their environment. To describe the interacting influences of behavior, thoughts, and environment, he used the term u80iYVqKe01+Bc2nydwvtOUabJtS4y8ectmDiQ== .

Assessing Behavior in Situations

To predict behavior, social-cognitive psychologists often observe behavior in realistic situations. One ambitious example was the U.S. Army’s World War II strategy for assessing candidates for spy missions. Rather than using paper-and-

Military and educational organizations and many Fortune 500 companies have adopted assessment center strategies (Bray et al., 1991, 1997; Eurich et al., 2009). AT&T has observed prospective managers doing simulated managerial work. Many colleges assess students’ potential via internships and student teaching, and assess potential faculty members’ teaching abilities by observing them teach. Most American cities with populations of 50,000 or more have used assessment centers in evaluating police officers and firefighters (Lowry, 1997).

515

Assessment center exercises have some limitations. They are more revealing of visible dimensions, such as communication ability, than of others, such as inner achievement drive (Bowler & Woehr, 2006). Nevertheless, these procedures exploit a valid principle: The best means of predicting future behavior is neither a personality test nor an interviewer’s intuition; rather, it is the person’s past behavior patterns in similar situations (Lyons et al., 2011; Mischel, 1981; Schmidt & Hunter, 1998). As long as the situation and the person remain much the same, the best predictor of future job performance is past job performance; the best predictor of future grades is past grades; the best predictor of future aggressiveness is past aggressiveness. If you can’t check the person’s past behavior, the next best thing is to create an assessment situation that simulates the task so you can see how the person handles it (Lievens et al., 2009; Meriac et al., 2008).

“What’s past is prologue.”

William Shakespeare, The Tempest, 1611

Evaluating Social-Cognitive Theories

13-

Social-

Comparing the Major Personality Theories

| Personality Theory | Key Proponents | Assumptions | View of Personality | Personality Assessment Methods |

| Psychoanalytic | Freud | Emotional disorders spring from unconscious dynamics, such as unresolved sexual and other childhood conflicts, and fixation at various developmental stages. Defense mechanisms fend off anxiety. | Personality consists of pleasure- |

Free association, projective tests, dream analysis |

| Psychodynamic | Adler, Horney, Jung | The unconscious and conscious minds interact. Childhood experiences and defense mechanisms are important. | The dynamic interplay of conscious and unconscious motives and conflicts shape our personality. | Projective tests, therapy sessions |

| Humanistic | Rogers, Maslow | Rather than examining the struggles of sick people, it’s better to focus on the ways healthy people strive for self- |

If our basic human needs are met, people will strive toward self- |

Questionnaires, therapy sessions |

| Trait | Allport, Eysenck, McCrae, Costa | We have certain stable and enduring characteristics, influenced by genetic predispositions. | Scientific study of traits has isolated important dimensions of personality, such as the Big Five traits (conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness, and extraversion). | Personality inventories |

| Social- |

Bandura | Our traits and the social context interact to produce our behaviors. | Conditioning and observational learning interact with cognition to create behavior patterns. | Our behavior in one situation is best predicted by considering our past behavior in similar situations. |

516

Critics charge that social-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

y/QME4gfl2r+Nk0Df2o9N6Efpp8Wk8p4NCsEnluPoFRbS44DTbSJxUZlNrRpuUT+1vLgZuWNap0Xo+qDEiQnBwlyOmrGEd4XopuzvbE+BYyi7QoUlj2J3sJhRpRUp1E3nvpn8IB/SFQyJ/TlExploring the Self

13-

self in contemporary psychology, assumed to be the center of personality, the organizer of our thoughts, feelings, and actions.

Psychology’s concern with people’s sense of self dates back at least to William James, who devoted more than 100 pages of his 1890 Principles of Psychology to the topic. By 1943, Gordon Allport lamented that the self had become “lost to view.” Although humanistic psychology’s later emphasis on the self did not instigate much scientific research, it did help renew the concept of self and keep it alive. Now, more than a century after James, the self is one of Western psychology’s most vigorously researched topics. Every year, new studies galore appear on self-

“The first step to better times is to imagine them.”

Chinese fortune cookie

One example of thinking about self is the concept of possible selves (Cross & Markus, 1991; Markus & Nurius, 1986). Your possible selves include your visions of the self you dream of becoming—

spotlight effect overestimating others’ noticing and evaluating our appearance, performance, and blunders (as if we presume a spotlight shines on us).

Our self-

517

The Benefits of Self-Esteem

self-esteem one’s feelings of high or low self-

self-efficacy one’s sense of competence and effectiveness.

Self-esteem—our feelings of high or low self-

High self-

But is high self-

If feeling good follows doing well, then giving praise in the absence of good performance may actually harm people. After receiving weekly self-

“When kids increase in self-

Angela Duckworth, In Character interview, 2009

Experiments have revealed an effect of low self-

518

Self-Serving Bias

13-

Imagine dashing to class, hoping not to miss the first few minutes. But you arrive five minutes late, huffing and puffing. As you sink into your seat, what sorts of thoughts go through your mind? Do you go through a negative door, with thoughts such as, “I hate myself” and “I’m a loser”? Or do you go through a positive door, saying to yourself, “At least I made it to class” and “I really tried to get here on time”?

self-serving bias a readiness to perceive oneself favorably.

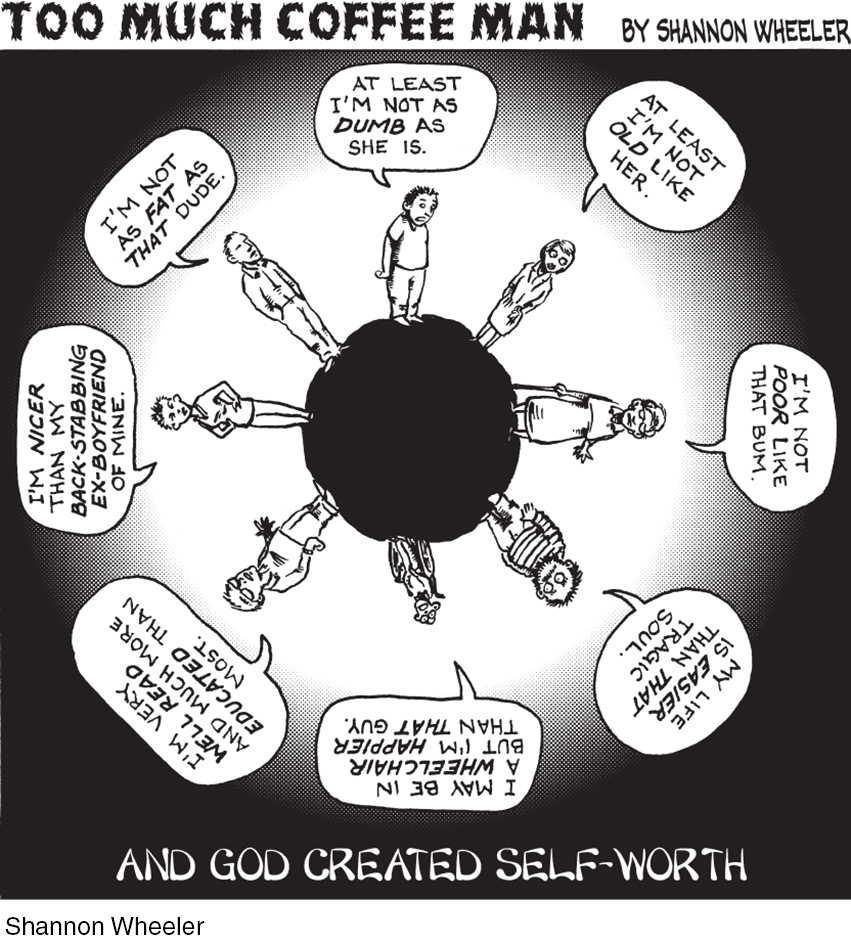

Personality psychologists have found that most people choose the second door, which leads to positive self-

People accept more responsibility for good deeds than for bad, and for successes than for failures. Athletes often privately credit their victories to their own prowess, and their losses to bad breaks, lousy officiating, or the other team’s exceptional performance. Most students who receive poor grades on an exam criticize the test, not themselves. Drivers filling out insurance forms explain their accidents in such words as “As I reached an intersection, a hedge sprang up, obscuring my vision, and I did not see the other car” and “A pedestrian hit me and went under my car.” The question “What have I done to deserve this?” is one we usually ask of our troubles, not our successes. Although a self-

Most people see themselves as better than average. Compared with most other people, how nice are you? How appealing are you as a friend or romantic partner? Where would you rank yourself from the 1st to the 99th percentile? Most people put themselves well above the 50th percentile. This better-

In national surveys, most business executives say they are more ethical than their average counterpart. In several studies, 90 percent of business managers and more than 90 percent of college professors also rated their performance as superior to that of their average peer.

In Australia, 86 percent of people rate their job performance as above average, and only 1 percent as below average.

In the National Survey of Families and Households, 49 percent of men said they provided half or more of the child care, though only 31 percent of their wives or partners saw things that way (Galinsky et al., 2008).

Brain scans reveal that the more people judge themselves as better-

than- average, the less brain activation they show in regions that aid careful self- reflection (Beer & Hughes, 2010). It seems our brain’s default setting is to think we are better than others.

519

The self-

Ironically, people even see themselves as more immune than others to self-

“If you are like most people, then like most people, you don’t know you’re like most people. Science has given us a lot of facts about the average person, and one of the most reliable of these facts is the average person doesn’t see herself as average.”

Daniel Gilbert, Stumbling on Happiness, 2006

Finding their self-

Can you anticipate the result? After criticism, those with inflated self-

Are self-

narcissism excessive self-

Psychologist Jean Twenge has reported that narcissism—excessive self-

520

Some critics of the concept of self-

Even so, it’s true: All of us some of the time, and some of us much of the time, do feel inferior—

“The [self-

Shelley Taylor, Positive Illusions, 1989

While recognizing the dark side of self-

“The enthusiastic claims of the self-

Roy Baumeister (1996)

Secure self-

“If you compare yourself with others, you may become vain and bitter; for always there will be greater and lesser persons than yourself.”

Max Ehrmann, “Desiderata,” 1927

RETRIEVE IT

Question

AXfrspfaB28Wszv7wl9XkepQJF4p99Wr8xNp7kwg+MOGRQuS8pR0Pj8lPYwLMNH8grPzlnLueVTI8J4PVsFIKbirtEOi32diWcEFVemdLYwCL0d5qJZBy2wJN/HWh6cspwhSiqwrXkjNknJD+3mu79Zi2hIG7SAbCnm8xmOYquGlXbqdPIlRmS23zCRC9CvGXOREn3A29EPuPDpBQuestion

The tendency to accept responsibility for success and blame circumstances or bad luck for failure is called

So0cdW4ARXdUQ6hCNceYCnY/HVtKUTFF

.

Question

t0LbW7nWXGtZWyzS/rkYDw== (Secure/Defensive) self-esteem correlates with more anger and greater feelings of vulnerability. dDlP/fKTyrYuJkUF (Secure/Defensive) self-esteem is a healthier self-image that allows us to focus beyond ourselves and enjoy a higher quality of life.

521

Culture and the Self

13-

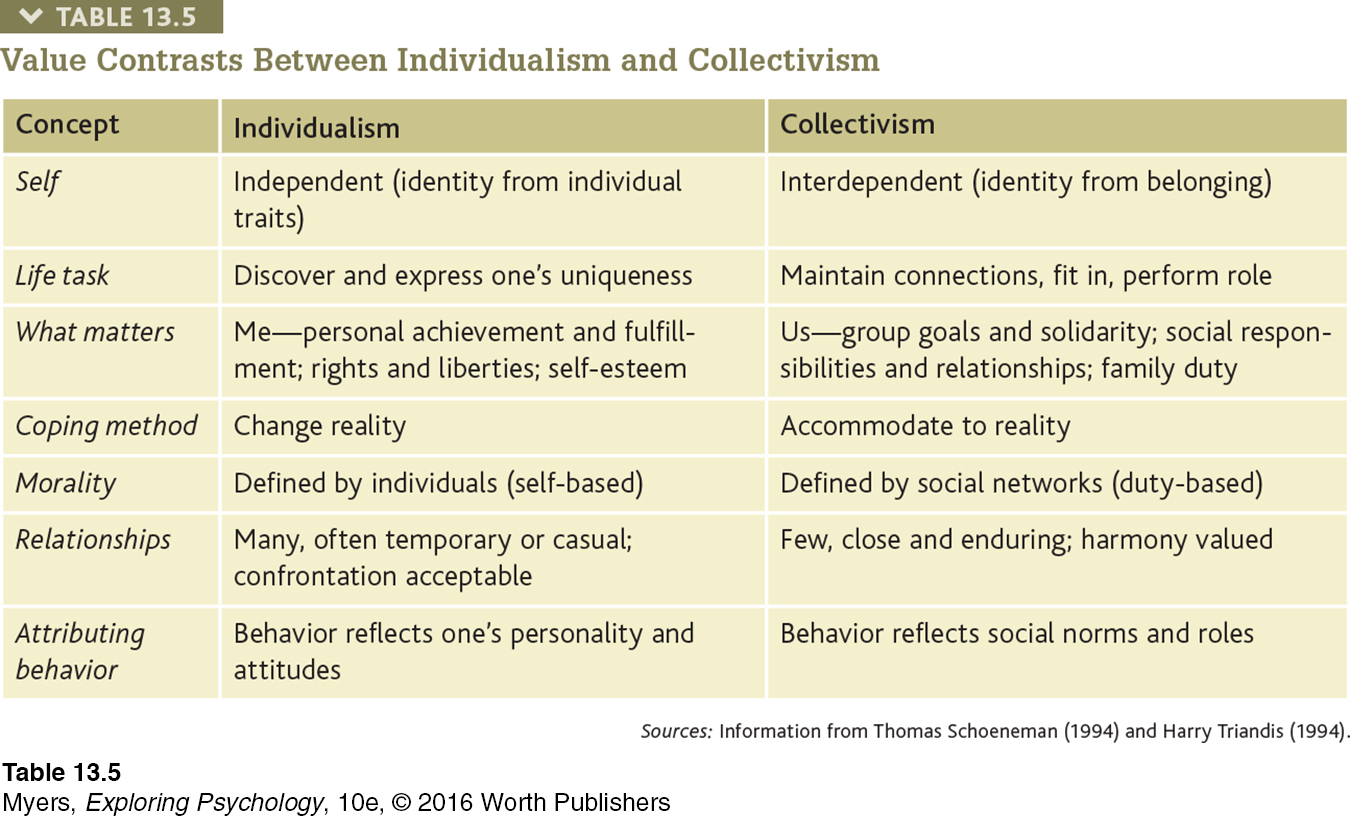

Our consideration of personality—

individualism giving priority to one’s own goals over group goals and defining one’s identity in terms of personal attributes rather than group identifications.

If you are an individualist, a great deal of your identity would survive. You would have an independent sense of “me,” and an awareness of your unique personal convictions and values. Individualists give higher priority to personal goals. They define their identity mostly in terms of personal traits. They strive for personal control and individual achievement.

Although people within cultures vary, different cultures emphasize either individualism or collectivism (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Individualism is valued in most areas of North America, Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. The United States is mostly an individualist culture. Founded by settlers who wanted to differentiate themselves from others, Americans have cherished the “pioneer” spirit (Kitayama et al., 2010). Some 85 percent of Americans say it is possible to “pretty much be who you want to be” (Sampson, 2000).

Individualists share the human need to belong. They join groups. But they are less focused on group harmony and doing their duty to the group (Brewer & Chen, 2007). Being more self-

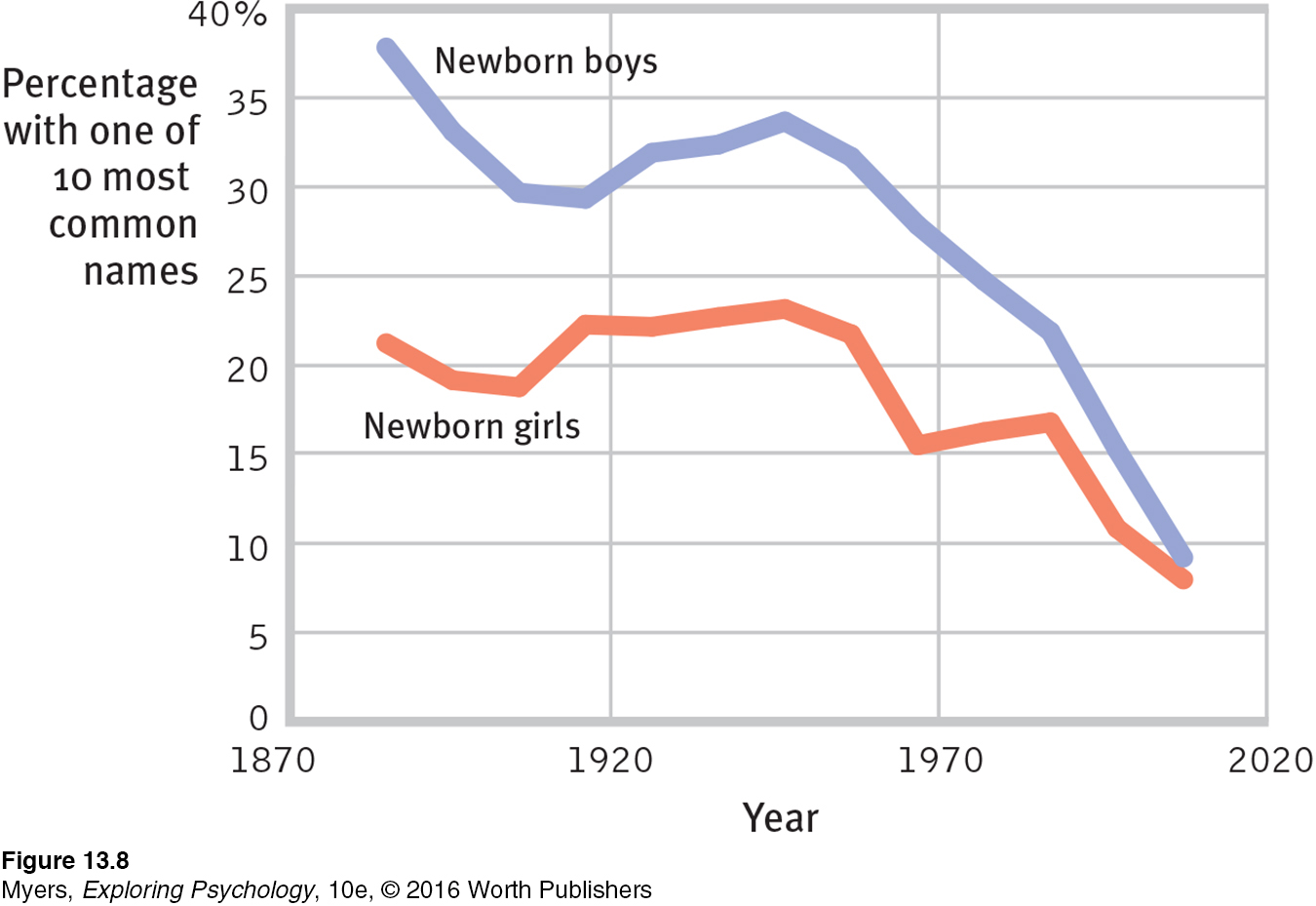

Individualists even prefer unusual names, as Jean Twenge noticed while seeking a name for her first child. Over time, the most common American names listed by year on the U.S. Social Security baby names website were becoming less desirable. An analysis of the first names of 325 million American babies born between 1880 and 2007 confirmed this trend (Twenge et al., 2010). As FIGURE 13.8 illustrates, the percentage of boys and girls given one of the 10 most common names for their birth year has plunged, especially in recent years. Even within the United States, parents from more recently settled states (for example, Utah and Arizona) give their children more distinct names compared with parents who live in more established states (for example, New York and Massachusetts) (Varnum & Kitayama, 2011).

collectivism giving priority to the goals of one’s group (often one’s extended family or work group) and defining one’s identity accordingly.

If set adrift in a foreign land as a collectivist, you might experience a greater loss of identity. Cut off from family, groups, and loyal friends, you would lose the connections that have defined who you are. Group identifications provide a sense of belonging, a set of values, and an assurance of security in collectivist cultures. In return, collectivists have deeper, more stable attachments to their groups—

522

Collectivists are like athletes who take more pleasure in their team’s victory than in their own performance. They find satisfaction in advancing their groups’ interests, even at the expense of personal needs. Preserving group spirit and avoiding social embarrassment are important goals. Collectivists therefore avoid direct confrontation, blunt honesty, and uncomfortable topics. They value humility, not self-

“One needs to cultivate the spirit of sacrificing the little me to achieve the benefits of the big me.”

Chinese saying

Within many countries, there are also distinct subcultures related to one’s religion, economic status, and region (Cohen, 2009). In China, greater collectivist thinking occurs in provinces that produce large amounts of rice, a difficult-

523

Sources: Information from Thomas Schoeneman (1994) and Harry Triandis (1994).

Individualism’s benefits may come at a cost. There has been more loneliness, divorce, homicide, and stress-

What predicts change in one culture over time, or between differing cultures? Social history matters. In Western cultures, individualism and independence have been fostered by voluntary emigration, a capitalist economy, and a sparsely populated, challenging environment (Kitayama et al., 2009, 2010; Varnum et al., 2010). Might biology also play a role? In search of biological underpinnings to such cultural differences, a new subfield, cultural neuroscience, is studying how neurobiology and cultural traits influence each other (Chiao et al., 2013). One study compared collectivists’ and individualists’ brain activity when viewing other people in distress. The brain scans suggested that collectivists experienced greater emotional pain when exposed to others’ distress (Cheon et al., 2011). As we have seen in personality and beyond, we are biopsychosocial creatures.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

dLE6tQjlAvjsjZ4K77NZG29Gv9HO46X1mApgzpmRleKQBXwjqLkpB6iX0bPfxCVht8JPPIGK33aL04DrqrJ7EyIbLX68yFP72C8t+7vPXzh1KA2NvBFfYH48FVhkR2U2b4VXoQ==524

REVIEW Contemporary Perspectives on Personality

Learning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

6XpHPyCgS27BnbDXfdNKEtOJCAw5nXdai8fFzCkEWuzrOhqF41aHZUZOGMl2Qr/JXHv8aXmb+eVjnO2vpN9Wv4B41x+T4Q0K3nPc+JiUDYOZT5oAOdJYB1JVWJ1YZlEj6uM0HbBSLY2owsqgUtUvzv/ONr/mBsSjVCSwDnRfM1S7emtOa8279LQA3J9T8MWV6BKqyeWC5sQ+hh7kEKRP+irgSW/tRUFRbqPCLA==Question

OigW5i8SlmASXMklPzpssFvRIbcraZObgEc/50Zdntpq7ZCHf/fuBe1xzrPvzMlAcLDsa8KeakLd5ph9xmS9zlUhuoHl63K5Pm7tEtyHlpw3n8Iy22ysniIRzxpLVqn5wCW1IF8jO6ujt9qSaZ7/ybog6nZtLoEMlS5gvS06bFBcFW5VeoXYajvVM4pG9qotLy+IKA5Be/dyWXuSJ1l97Ofl39AtADjiKu0Kqg0DpHOXFeZyW+2iswbkiDSt50YdsWrFS2dytmbD1a48DxPQ3+zlnsjb8TIdEvBzfMGts+yg6+9o0VVSa3ZWyRs=Question

ABbtdCvsHoyGmPn97jvGejWfDpyxCxZ7u7Mob/VEkb98ey0xhObTi9BY2jygaq/5Yd6Bp9f8R+CYxmGEDD/sWEBnHCZRvt6YDrKueeWGqta4qhWSoJpGNerMjJK7GbpYRzOZ233yrDzuiCzI3Kt7+LZlAoCMLSFy7pB04z5cPo+LQyiNhw0+du0N1TNRN481OcBj+Ch+Y4HBT4J5FIEb1Mw0DjiiX8YP3QdsER1X043Tt+BEAnMbdiPCAzq0zofsBE04JT4UUhczFVv+m93ageIl1eEcv2gRnDXxn5T/SrqDMsSwaL9z0hHe7trXkczjDEJqZfb4BeZnlaYveCv8Z5L52pCuRFv+1xu4QQ==Question

NkIf8MnfhqBuRRSCBuxvPnqldsq1qIoSVqnYTiyoKk/uDbvdJg6icqn/DK9CWIV4eH1rN6qCNnDHUQXbq6XOanfUCjbNOUCts6OShFqMsgPnprsNfuZRcbHzT61OtaLD/9KBkhT1etv1aDDijrnJpnTo9FHzbxENl5iKCvZh36EPTH8xF5VygORYGlBj+DMUROfdfNtlGf4Zq0qw/9bWMGvJb+Tnak4t+NWE95UmVDziLUkGCSiboiCO/1k0KuyVfPwylt3Xj3OtRUQpQuestion

L8OwVYOUz4NQl+oguekGdjFoRlxfF8nuUrrriEnQZAIg+P6265M7lNd0P4Hwl47iNVhniCJfcrBM5V87E1K/b9UiQhU0GnuXtSPjYig4e2oUUcCtLa2sygzXXip3zO2oykmkwVhhfniC2j1K9O3najn11iighwi/n2NxYGVvMWfsGIN/4vayNivt+7bXvhdBB9mc5T1Oy5SapYn0wdNuIwXnhW/XOJ55oKMDktY/JKkDv+sSSEgVRz811unYnenRTQsVkGOblqhDnLZw+UDALQ==Question

QKz/EI+7f8lC7JMYfVC1uk4lQBjfl7FEE5Ox2fYxL+vbqjq2RlIPw4XL+hZND0FtdUHW64cNQOAxwW60HfGfJKIXKMw6M58vgcuWgfMcwL4IKLT02xBC+G0/kX1sweb+RF4Bsyk6S2P4HXttlCDwNgxz5gnUwLIK95h2dw0qMvpe+75mYNugt3PeMS/ijqwYlZRt76PVlwRg3oW5lvj65SC0mxAubkL/nR9VnaoeTEwZp3SNYX5oImzGKdra2OLSkyvJZ3xiUtPe2uknaMnem/WiGkbEH6ye80zKJQCgmx+QAvZOD+JOpecaxWjdSocoyYPoNxMYXmuLcP1B4QHoZZeuQSk=Question

V1nm+V9HRFYeniTAQfoXaL2iuoFpfpQjtLZzLXYvLLDW565+oPk7Q0cLmW7n6xCefW0a3u/nOWu3ZS7p/dpj31Wyz43DarwX2tuuSMqNrHw8LpSGZZU/1zlQwuZkSvE6683dgfm+AjsaWUHYR8jhmNM7343wRpgoikqWFa3b5wdiuT9jUAoBmEAijMnrYA5M0+fIbz0N240pOm5SUEJ54C1CYKRTHZy+SWtkoPIY84lWkzcC2xvdm1uhvjJVjXjKAfM3//QSjvVBcrlEKh5XVlUgANKDkY84y9SH+g==Question

qOMCVJIl1blAUbm01qPxfWRR3kRAcst1pDHQJ9Wt1+OPW4o2ETzSAvYFwOShvMNCm6C0pk+vFVfuRjtTLAjvAY5YsUDMwqi1zktxzsdxlz6Vs6Fz7G3ft+AH/wj9TKlqf+18RyfkfhimBOn7mJjtCnU6VRkkQUyuWyItDKvW6Xch4yQkpGHF3EP0ezcPM4+dsxCdJzhDFvJnzMY063ENpaD7jIvTB84Ui5g31EQhR+7T5Fn9AbreLDyIXerVaw6dZMNdrWS1fNNy6wS/5y/3G1+WrWtm7y/Iq8x1cyMX3plDR9iNDwWJ0lkveEW8P+cnJt+eUcZ4MdhSE3ZtAhDfRL0i6VsbTR36Gkmy87bnnnAXBnM4IzDtmmYdNWni+bbxxjGpyOnIkmbM1gWBCs4ecmlMJerXJhd2xOJQtw==Question

NG6Z/RoZG43d1Yz8tTg64xSG5frhqL1aT6v5cSU9bwPtY+w8BTTlEuYEZk3wmo5wXLWZF6MI7owlcfS4SWNveQBFE2fjYR0/eDvThRqxKneirn3UsmfIrO7usz+avIOtxDe2kfhjZKvzTQ/7KTivQsyy9A+k9+7b3evr2EhMzUoxBll/A1h40bqYucxyiRyUCOF9v4T3mMQwVLSVlTBxKrodERBZcC7U0MGYTyyJHynXmury9byMBQITiuyqd3ukvxO70p3BVb4VRLBP8HTKpBP2EqJPcsE2/Ogsntr0r4FQkOpeZu825BRkQaGZYaQjxxHeYkp06a3ALuBF7/cf3we7bP1pUfzVMexUEJ8WO4hTEmq5nxay775A4JbETFO4egCo5IZCTVjRF6eswE0CtA==Question

VBnW3pSbF64eQBAJrmLSYApQWeQ0vpRAQcvVef17rlTxVyjxunmTB+H5SzneDfNnzkFVLJLDzSfX2VpBMRMpseaKmv10ig8i/RaxlLOVdcOebJ6YC2DkYuU02pftFXRuE6yi2OgmbtNdlU079jjqrSMaMpDprXMaXC9dvhNTCwTSCW6B4GMj3xtYoDZP/STKV+wfUMDdJv/wrbKyRSRmUheKfcRhKgBxLplzmtshiIj/Tppgh2/yyhrFZN8pkHFr92MJ1Q==Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

wlKtOLnL9iSoD906Gzo3I62rfTq66QQtNBCAEDZ63KM3JmCpH9iqvbRgQirkTja6NdvuJA9X1VLjLJAvTG1tGl/N+9rXpF8jxIL0PCyudN/IBRZwMNiNvYOXQLktLoyUP3Ed1MiTzAe1B96//+o4DZAo61EIhqf10WDCvVyWcz0MRfK0oUdoS1I8k4NXRU0F2QKwEKExspsQjl6WGfoBKJR078wjfqYiV+j9o64swDfN9+2wjuRgb7P1ViTaDOCg5BRR8ikj2wYf/s3dmJDV6XnAqFaVMI22EpzjI85Rw6KPfzJDebSQCLSsGev06uT+1yizeXmZal12gAuMrES6fc0P8xaX5gpCBtA9wDd7+1GA1sUpZYxcZXA6pLcoSAMQLqdaAkF6ZGIKbTdayJkLL+ZbH79/lf+uUl6GHI+y+tG9Fr2w4VUjPpltfbu47ivJOpM5e8JS/yhAzWU94NS+zBwo4LgGhi8XnXGBz2Ay0HfLQeyVMMXUOrM1IIFxujzK0y2a5xqCEVLrTm0OaejSYa/MM/RmLAdrG/Pt4kNi2fpOv45rmVe15fU3AxZeoJoi55lYy4c/+rG6HBH+M8r2cnrVnDLaLIphNlkPpMrTQlBRMiOH38XjLYgWEDAtXwfY9MzoryqZOpmzYrFNM7r2+HtGZzuxre/u6OCPvJwesNoWZfDILtrmYtIU2k7HCGKDH7oxBaGF6NPGFCZQEbg99GbdCUGEckhltIYRT1JcCmCylN+UwW3KQb/Pxg5L0RMHT0tzVn9MZENs/VkcKA4t+8r8Qm6vAWELY1upaA1+bIMn/ayK9WT2BEq++6H6drXAkaG7OXB7VOFC6rx/RxbzsC2K8/stK9VsSYfjZ4C0tYzC9jO5i1vripYyrEwJXIL2nY2oHeW/ovCFzVCiVzjHqyG2lBXcxsWQIsnGs5kM373fdRtOzu/g2F6RcBVMsDGewJ+v4dG3ubi4o5IMp8fW2tKPOaly0YLG2SY86WBY/w5FB0uVelEurVFGLWr01Y+8IG7MaVvSdAhgnRcn7YnHdY76VEYkCuD028h9fgRJtwruxv6wyAvUgai5gEBo7a5oOW/DWzIZ+p0as0B8c55A47MI7Gy6Vr9/+XVIwLX0m8HspQL0u3xff3/KAJcBegECaWSekq+OsTmRKEAQ3FV/CR8/13lJARONWE5l/gTYI4kLCFVEhos8S81gzNfjSInjky8TTPgNJO9HgbLjIm+p+pacZrllOIS9lFAMbQ4qOKmPiHAcKdJYjCUgt+3t0PSBP0LFx4s87UwZ49yMwpMauG24gbjfCdj61P5UqzPWQBNf203pIwxY2IpVuq5WctA6IZi0so2o2YLyLQ4lA6DNydlO+qna0CoE7URTDH3sFT0ELAPsnN9pXDtTVce0ZlAtQxiBKyBwRd5hbaOUUTW3uuqnVWisNgBderrHXUYuBdFjP/L+KTg7gIB0aRUg+nVBco9GYwQsZDiiQSfjRBhV/MrWUONA8NGgthU9yZb60KpJwVd5HhjJaP+P7ZiSZVcsHlGyBoPcGv3Kg42v33KSyk4ULWjZWBayGT1ognSffnyC0JsLI8k5IY8pDJJsPQiBH3oG0BpfdYQj6583Hz87Q2qvg8rWn5NLjswDc5BidBqBjam7gywhYulX78wiEmAWH8QNmRa5baF1K3p1vbIxHrTPAKrzpY1ajvmvJ26+16Ba6LydsfqYGd92rDYAdQ2eUW/MGIXssq5zeX2iCMGHboKuquSqywF2J2+dArnTiUalbZbYXc5u5vX758d3qJek98wtOX1ZloVMbINrXEmGHn8EvW7pRDLstfR8OMQEFa30c3tyKm7dbGB016CR5XtAlR78G1+WAI4cUcwEf32uwNnClEgbmRh+R5sNk1kGZd6CneSZDKLcvP3gLN+yOj0WIayUydIvyMKgQGfpBUYvZkHhozWIybWmDQLJOsH5jD0Bp58hjPwVHKcoh+jA7qQdnuKbOspEFW3GG2/mElH5Kiz9Rlp83y1BhNerVNiMPEaE9zRHojKkI+IKFYP41s+cqxod8rAKXBaxv5mpfhoHYv3+g2GlxrkCuShib6CU2bHLzgQfwbshAzlZbGXYbc73jKP2ZOuHl/XxV0GsrUBv7BagKzYcvMxRf/b3R0687r4E8odeIYIblChbBWEJ2ZsAEFHuHAUSLwMVHOVbxXkhJLEGTyie32XjiEwn3GU1TkTRUoIpGDe8m26ucCOShKrGlxqm3Qtpq65wF8JxnjXPIcBiZxzHGTUXku+ercRizSOy0UNl/skY7egKIveFlmxJFzhtwBGZasxui6v80mYoJaa7d5rjEC46yuNtdtJf790b+ip1Cyn8ZaY23vDLylTnvqdBzRYZUgwyoUrEibklVwe1vcFYi8spHNIAT1yckzWixhqLCx55DjkJ4oHOxaRizRkZ4ZdjMxI7Yhj+0BdufZ42OC8K7kBNYJn0ha0kTrQdjRj+p7Tc9YMAUW2JNyduaAGeEhav5lJzgl1+L88xzu+nDu038UbS090lGTFDmjNUr7QK8d2MvQPqaNk+vdBiOAGVXRVey82mCv4SnTceL704EwttC4wthlPZviuFojyNC1BiR/BXSqKi9g63hHaqTJIwOoheJB5uQx4N6kBxfikDe+VXTNXV5av48vBY8Xylf+FImHWa8U+gOI5lyyKobqOPuFUmojco++yrGCIExwgxFduJ2OPuQT9Gr3fk51xGFz0LnnQmg6na0dA=Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 13.13

1. dM8qpdrAP83EAXf3 theories of personality focus on describing characteristic behavior patterns, such as agreeableness or extraversion.

Question 13.14

jaiVZguTbigz5eMzv9yA+O25xJ3sPZ0ijK1mv1JVDRRWe3a3C816DiwogA4NPmZv1YnNy4PojVRG7EI+oN2P53iIHobJghuTfAhsruFUMZvTiX48jKfndVOV8b/Z7dYbkQ5O3NUDzI8nGSdGLfCuJM/UQzGH768e74Mezk2UDFnNoEis5jePZ3WfMFGT4zk72JqXdKcGOWPGfvWlXQhmR3A/x0ysNOWgjiqL4zbwuixF7WocrFhWUkOnAcXbzEaiUF6xrnk+RbUKmBtBjWC5oMZ388JVIz0nmRPDRIx/AW6HM+TcE97KSmhZQfIMoV6UA3VQQBy6x7SPK7tqJpYF/KFABgRluSVdpa9ZA2C+hiY2V5FcjkvN8g==Question 13.15

VwcijawockRopcDngGiHnAtl5FkMOtcCGb7ElWjteaM9U9SmIVghbnQKgqpZhzOe5RXdtFreFfvEK/Fo9lotDDU5bmXrnWZTMedFSiKKJPr/f/3LPbTul4ly2YT1mMHIInM0MKW/1x2++jzIHAAtTNPn9CcrIpTpq0gWiAic4u5rTpNPMTVCfgjoHgd42M0/ZyexBiu/olQUCrzriou58H3+8YUhDNJWnATiUjCySyaO9/G/qIhdnnkaJbU=Question 13.16

p75tPrnm79ewn7bTQAQaJhPra9WbXIrtV9gpWwPARpvKg6Erp6P58gOg1ThRxusrQE62YC7HD/ufej5VELSTtTWRdExDNdvxq4yrUPmoUEJ1yfssX6HiHZIhq5z+0AbKnpM/dkunUvvvD0n6ExCxTDBc3xCqDjdmltkdngSCovCcUZJli24qB2MCZwTrvkdrAL8/iERD+o510ML1AK9YxFaPbv1y1km00EPSzYOOqNDleWXEPAMBieO/9XIea79gJfvq4VyLF6FsLc/GkhNGJ+yQg2ni/7Wdn65gr9zdBkuTQTXFzc9f95jGL+dNIP5kuY8fdhDrs3XmI7yMDAw19N/clDcMngbUwQ3jdcinEOJjtobdudbsTkQo5c4YlCsdH9U6cIMkb4aYPdu6E6le8Q==Question 13.17

00Xi7O6Zgply5xQ+8kCorPvxQdq0WmUdxLl0cTFfn8SxfL+n4Ymx0y2wFijfItQHZEmL5MsxdO4ZqucnvyaXE+6YIqrOkZsh/npNJgO5STO8sGhfMZn+6G3haAf2gOfqyB1h/5nfRX83pSo+2TLRt+f2+NjWpgmKU5cVQHpwxhWt1RJLV/WAzcd1oVvuZ7llglMINTswSIG9Fw6Ypq+pKG7kImAZZemvU7jTXy0VHUskMwIP/pSXjdwy5Cp9hh2JKN097bMCLiEhG1LOQOUPFUrwDFtZe+O8FZWp8RA97UkKxOBcOTBgH52r3MTqh1YGmNl+CpSRJZOt08LXnepZjVtXY2OVW/sgNLb9JuYF7NqkQZ6UC+vjsehbsaWrn/lrAX31uM6k1dcMy/zlJ1dwAX2pdsz7s00Pw5dOJqf1Hs93OefOksi7b99IQkil1XszHRBHWr3O7ITb0qbAfXzHOohm22ty/u0k5zzmAa/kBbCg4TcExuDetZ996wWpfO6gb1qSFhesbKyYehPeOT6ov9voYB6tz1mnMuLNwl7MKu9E8f4FsWEFgvSEG13QfuBgjKO8Bw==Question 13.18

6. Critics say that igHlIUiSeAg0rbJ0ntl4jRx+OhLxx8J7 personality theory is very sensitive to an individual's interactions with particular situations, but that it gives too little attention to the person's enduring traits.

525

Question 13.19

JEnjbEtbyUbUjZzAZsDO6oluX+ghcLM1tuYD4tQ0IySa8V/dB3YvW6LJTa21J1URl6UEjRGT9dsoazZngcJAE2MlK0ZIeqGV7PC6RjpdFp7G4YDW+DsupEkDl84Ca2EnJ8mpsoTEH2qccLLXkhAXpMVFMWaLUddNhkNx6YHiqA6K7KaUV96rwGLSjXsLGo+Ft3QOTGDZLWASyNl9NLsmdRI+4LlhpQ5SBbL8BlWiX+SwSmzGNvJ1y722kOx4/fI69cWArIf/0WbZA11OpSjVPeueMVHvNBmPnnt/dYsqP7QeLEZdB0Q2ulINz/eY8jni/NXbfV7EddXaaRXRzf6Epqc0uqOdbzfLg8BL5DZ6RiLGt+ODCOhABNKwGm88W48/eIqL9H83qVahqhuTeLRRtEJhw8kLxSHfZY12NPR7vS08DlKpmMbC8lyxzYsiJMyB+VQRrHWS82ab9vxtZBSHskWMMMBHSAhZQjgPNh5vMwYeXfnU+rrL+54UMeJy7NEGTdyLdnI9Qlo2QMVFo0AxVfeCcpPgA18ibAdx9UJ0EzSeSDTnD8Wge9PE09GhiAPX52KZHn1oQgXvGcVn2BI7BNT7X7LiAIlQ0mACeonEcYKt5kDpG1Q8ZjtNWNL986T3jzhgWiMIsX9Z1QXIRVWmgd0EqIdfs0sywG5R1gp9vZvrscjNQslKR0Ng4i8qZOrs3p3p72IVyggbvC/H6ghncY7EdgdVAwiSfV+aPK8zRqlAvxXL1lxZVs5M6p2YHCJIFv4LCwmGDaTcNCmJA7WgKg==Question 13.20

yzYFvrMnUUB15PYldAv15rH7ViNp9pAuLVVy4ejr6uORxT+PS3qUC58Lc5Kw+i4MG3r+z1jpVyEPss/grVw+E7RAOKGnaiN/XbER2QhFIBNmFRkbAY42hJxYGmT38frT1R82ulu/WQdvXOZyGUjuVt8/U3to1zdg6FYq946tURH2USdsyeFXlZi/jq4o6Cx9chgpSpR2YiWuLbpRB3zTDr9zpB011HzYkrkmCRKHTUiRGmvLIhORPrFpoQs=Question 13.21

9. The tendency to overestimate others' attention to and evaluation of our appearance, performance, and blunders is called the CNXcpCEfnSKHhHQ7I638gzHw6HGKUFy2 .

Question 13.22

5XDEICa25QaS887kEWYjlBy4q1WllX6LPsTII77w2AT995lhLM5AMGYTno4o5E1R1nQPwnzsSl+L0QMEK/pN3Af9vgkdOZGrmjlzk6nub3JGSJs5GJRaYHRsX6PN6vcy+FnmFKTOrtD5SlZJsoVsGt2JruoT61EOLrZDlY1hUYdZxI2nMJ57ZcqJU9tXFvnkKplxpZ3eg8eqexhJQzXoRDbGl+SD9dKVA0qBOgU6xpze6iaN6Q1/U/L0TplGkK6pKr/+dMdUABi1zICs4SRcpbnGrVIsnz94dGVY5Sj9sCyscyhQxVX+aFBmNXBGkvLdGUz8DmNzVaxRAOalyivs8Q==Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in .

.