14.4 Schizophrenia and Other Disorders

556

Schizophrenia

“When someone asks me to explain schizophrenia I tell them, you know how sometimes in your dreams you are in them yourself and some of them feel like real nightmares? My schizophrenia was like I was walking through a dream. But everything around me was real. At times, today’s world seems so boring and I wonder if I would like to step back into the schizophrenic dream, but then I remember all the scary and horrifying experiences.”

Stuart Emmons, with Craig Geiser, Kalman J. Kaplan, and Martin Harrow, Living With Schizophrenia, 1997

schizophrenia a psychological disorder characterized by delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, and/or diminished, inappropriate emotional expression.

psychotic disorders a group of psychological disorders marked by irrational ideas, distorted perceptions, and a loss of contact with reality.

During their most severe periods, people with schizophrenia live in a private inner world, preoccupied with the strange ideas and images that haunt them. The word itself means “split” (schizo) “mind” (phrenia). It refers not to a multiple-

As you can imagine, these characteristics profoundly disrupt relationships and work. Given a supportive environment and medication, over 40 percent of people with schizophrenia will have periods of a year or more of normal life experience (Jobe & Harrow, 2010). But only 1 in 7 experience a full and enduring recovery (Jääskeläinen et al., 2013).

Symptoms of Schizophrenia

14-

Schizophrenia comes in varied forms. Schizophrenia patients with positive symptoms—

DISTURBED PERCEPTIONS People with schizophrenia sometimes have hallucinations—

delusion a false belief, often of persecution or grandeur, that may accompany psychotic disorders.

DISORGANIZED THINKING AND SPEECH Hallucinations are false perceptions. People with schizophrenia also have disorganized, fragmented thinking, which is often distorted by false beliefs called delusions. If they have paranoid tendencies, they may believe they are being threatened or pursued.

Maxine, a young woman with schizophrenia, believed she was Mary Poppins. Communicating with Maxine was difficult because her thoughts spilled out in no logical order. Her biographer, Susan Sheehan (1982, p. 25), observed her saying aloud to no one in particular, “This morning, when I was at Hillside [Hospital], I was making a movie. I was surrounded by movie stars…. I’m Mary Poppins. Is this room painted blue to get me upset? My grandmother died four weeks after my eighteenth birthday.”

Jumbled ideas may make no sense even within sentences, forming what is known as word salad. One young man begged for “a little more allegro in the treatment,” and suggested that “liberationary movement with a view to the widening of the horizon” will “ergo extort some wit in lectures.”

One cause of disorganized thinking may be a breakdown in selective attention. Normally, we have a remarkable capacity for giving our undivided attention to one set of sensory stimuli while filtering out others. People with schizophrenia cannot do this. Thus, tiny, irrelevant stimuli, such as the grooves on a brick or the inflections of a voice, may distract their attention from a bigger event or a speaker’s meaning. As one former patient recalled, “What had happened to me … was a breakdown in the filter, and a hodge-

557

DIMINISHED AND INAPPROPRIATE EMOTIONS The expressed emotions of schizophrenia are often utterly inappropriate, split off from reality (Kring & Caponigro, 2010). Maxine laughed after recalling her grandmother’s death. On other occasions, she cried when others laughed, or became angry for no apparent reason. Others with schizophrenia lapse into an emotionless flat affect state of no apparent feeling. Most also have an impaired theory of mind—they have difficulty reading other people’s facial emotions and state of mind (Green & Horan, 2010; Kohler et al., 2010). These emotional deficiencies occur early in the illness and have a genetic basis (Bora & Pantelis, 2013).

Motor behavior may also be inappropriate and disruptive. Those with schizophrenia may experience catatonia, characterized by motor behaviors ranging from a physical stupor—

Onset and Development of Schizophrenia

14-

Nearly 1 in 100 people (about 60 percent of them men) will experience schizophrenia this year, joining an estimated 24 million people worldwide (Global, 2015). It typically strikes as young people are maturing into adulthood. It knows no national boundaries. Men tend to be struck earlier, more severely, and slightly more often (Aleman et al., 2003; Eranti et al., 2013; Picchioni & Murray, 2007).

chronic schizophrenia (also called process schizophrenia) a form of schizophrenia in which symptoms usually appear by late adolescence or early adulthood. As people age, psychotic episodes last longer and recovery periods shorten.

When schizophrenia is a slow-

acute schizophrenia (also called reactive schizophrenia) a form of schizophrenia that can begin at any age, frequently occurs in response to an emotionally traumatic event, and has extended recovery periods.

When previously well-

Understanding Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a dreaded psychological disorder. It is also one of the most heavily researched. Most studies now link it with abnormal brain tissue and genetic predispositions. Schizophrenia is a disease of the brain manifested in symptoms of the mind.

BRAIN ABNORMALITIES

14-

Might chemical imbalances in the brain explain schizophrenia? Scientists have long known that strange behavior can have strange chemical causes. Have you ever heard the saying “mad as a hatter”? That phrase dates back to the behavior of British hatmakers whose brains were slowly poisoned as they used their tongue and lips to moisten the brims of mercury-

558

DOPAMINE OVERACTIVITY One possible answer emerged when researchers examined schizophrenia patients’ brains after death. They found an excess number of dopamine receptors, including a sixfold excess for the dopamine receptor D4 (Seeman et al., 1993; Wong et al., 1986). The resulting hyper-

Most people with schizophrenia smoke, often heavily. Nicotine apparently stimulates certain brain receptors, which helps focus attention (Diaz et al., 2008; Javitt & Coyle, 2004).

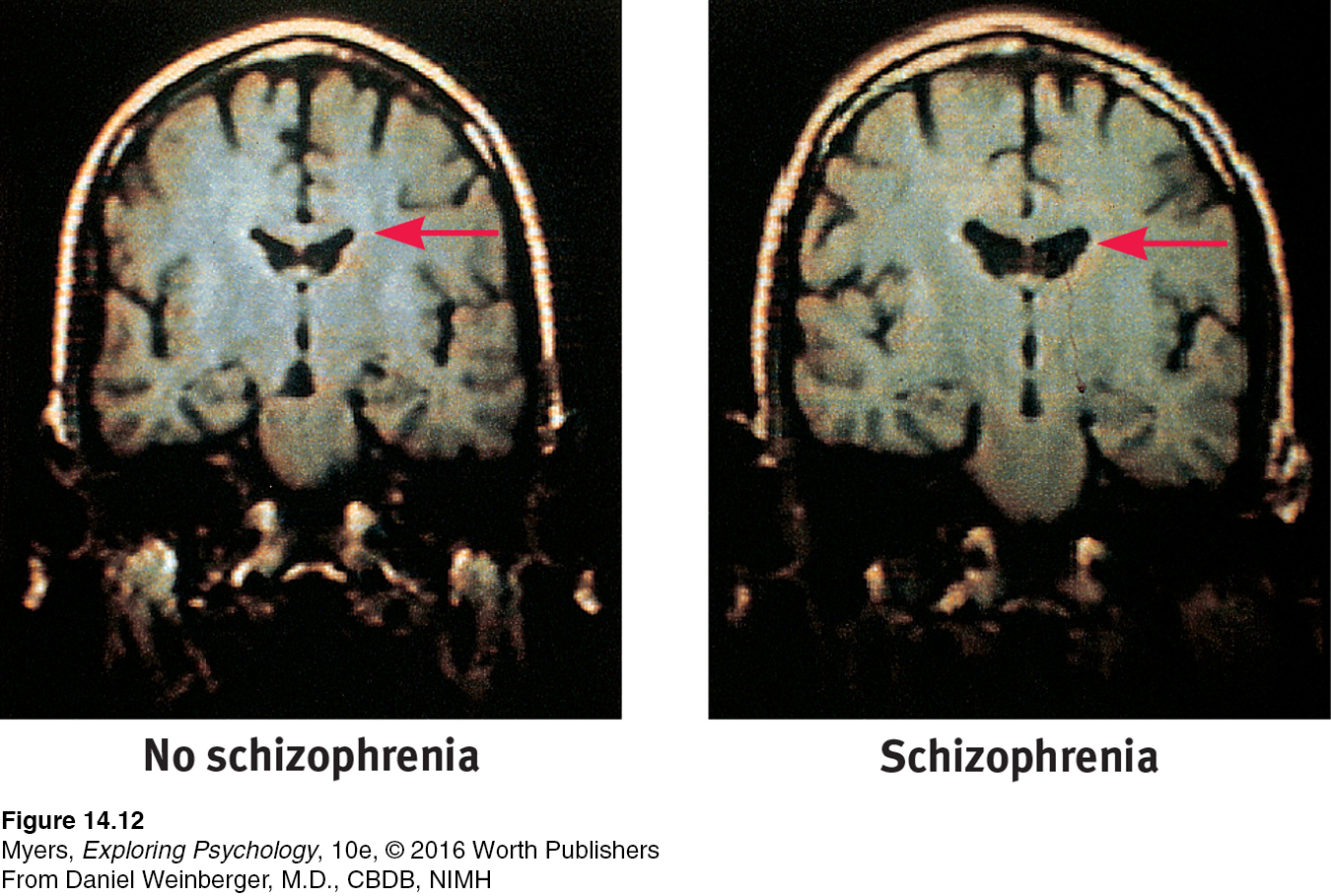

ABNORMAL BRAIN ACTIVITY AND ANATOMY Abnormal brain activity accompanies schizophrenia. Some people diagnosed with schizophrenia have abnormally low brain activity in the brain’s frontal lobes, which help us reason, plan, and solve problems (Morey et al., 2005; Pettegrew et al., 1993; Resnick, 1992). The brain waves that reflect synchronized neural firing in the frontal lobes decline noticeably (Spencer et al., 2004; Symond et al., 2005).

One study took PET scans of brain activity while people were hallucinating (Silbersweig et al., 1995). When participants heard a voice or saw something, their brain became vigorously active in several core regions. One was the thalamus, the structure that filters incoming sensory signals and transmits them to the brain’s cortex. Another PET scan study of people with paranoia found increased activity in the amygdala, a fear-

Many studies of people with schizophrenia have found enlarged, fluid-

Two smaller-

PRENATAL ENVIRONMENT AND RISK

14-

What causes brain abnormalities in people with schizophrenia? Some scientists point to mishaps during prenatal development or delivery (Fatemi & Folsom, 2009; Walker et al., 2010). Risk factors for schizophrenia include low birth weight, maternal diabetes, older paternal age, and oxygen deprivation during delivery (King et al., 2010). Famine may also increase risks. People conceived during the peak of World War II’s Dutch famine later developed schizophrenia at twice the normal rate. Those conceived during the famine of 1959 to 1961 in eastern China also displayed this doubled rate (St. Clair et al., 2005; Susser et al., 1996).

Let’s consider another possible culprit. Might a midpregnancy viral infection impair fetal brain development (Brown & Patterson, 2011)? To test this fetal-

Are people at increased risk of schizophrenia if, during the middle of their fetal development, their country experienced a flu epidemic? The repeated answer has been Yes (Mednick et al., 1994; Murray et al., 1992; Wright et al., 1995).

Are people born in densely populated areas, where viral diseases spread more readily, at greater risk for schizophrenia? The answer, confirmed in a study of 1.75 million Danes, has again been Yes (Jablensky, 1999; Mortensen, 1999).

559

Are people born during the winter and spring months—

those who were in utero during the fall- winter flu season— also at increased risk? The answer is again Yes, and the risk increases from 5 to 8 percent (Fox, 2010; Schwartz, 2011; Torrey et al., 1997, 2002). In the Southern Hemisphere, where the seasons are the reverse of the Northern Hemisphere, are the months of above-

average pre- schizophrenia births similarly reversed? Again, the answer has been Yes. In Australia, people born between August and October are at greater risk. But there is an exception: For people born in the Northern Hemisphere who later moved to Australia, the risk is greater if they were born between January and March (McGrath et al., 1995, 1999). Are mothers who report being sick with influenza during pregnancy more likely to bear children who develop schizophrenia? In one study of nearly 8000 women, the answer was Yes. The schizophrenia risk increased from the customary 1 percent to about 2 percent—

but only when infections occurred during the second trimester (Brown et al., 2000). Maternal influenza infection during pregnancy affects brain development in monkeys as well (Short et al., 2010). Does blood drawn from pregnant women whose offspring develop schizophrenia show higher-

than- normal levels of antibodies that suggest a viral infection? In several studies, the answer has been Yes (Buka et al., 2001; Brown et al., 2004; Canetta et al., 2014).

These converging lines of evidence suggest that fetal-

Why might a second-

GENETIC INFLUENCES

14-

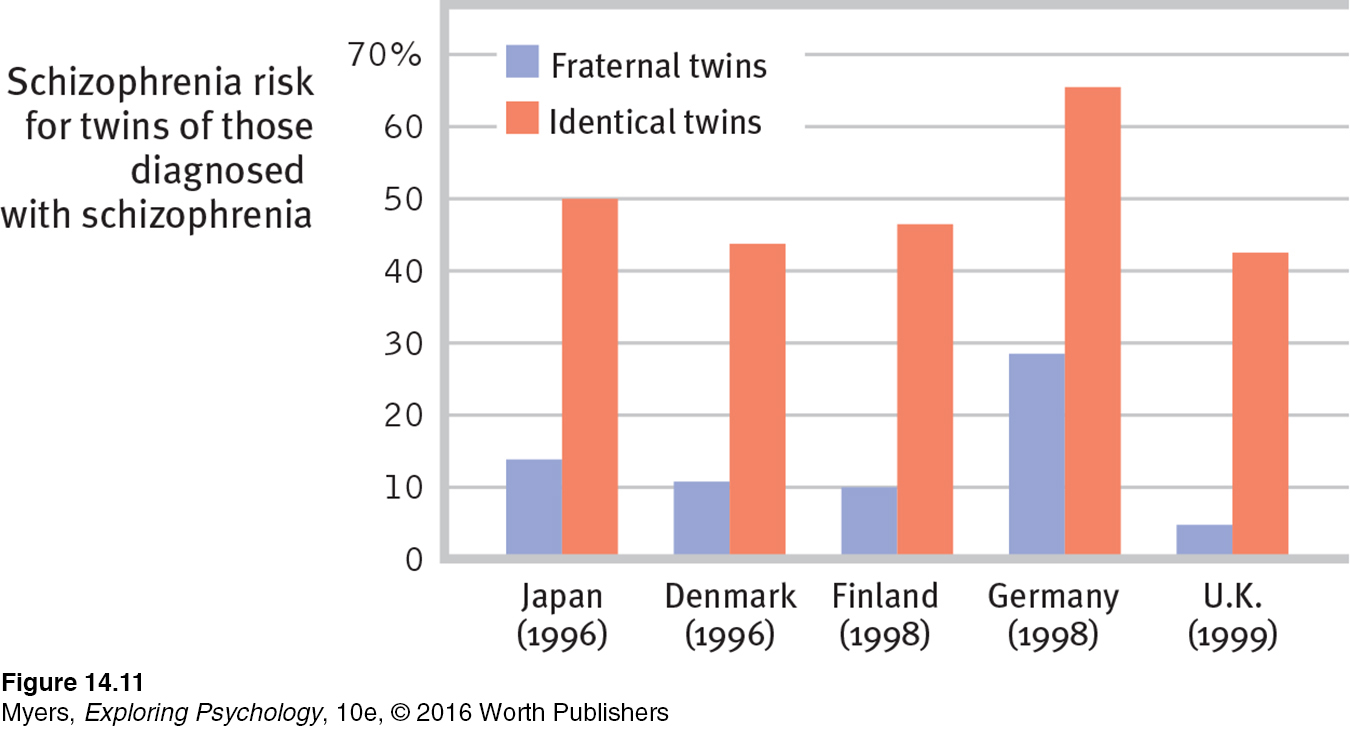

Fetal-

560

See LaunchPad’s Video: Twin Studies below for a helpful tutorial animation about this type of research design.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Twin Studies below for a helpful tutorial animation about this type of research design.

Remember, though, that identical twins share more than their genes. They also share a prenatal environment. About two-

Adoption studies help untangle genetic and environmental influences. Children adopted by someone who develops schizophrenia do not “catch” the disorder. Rather, adopted children have a higher risk if a biological parent has schizophrenia (Gottesman, 1991). Genes matter.

The search is on for specific genes that, in some combination, predispose schizophrenia-

Although genes matter, the genetic formula is not as straightforward as the inheritance of eye color. The new result confirms other genome studies which show that schizophrenia is a group of disorders that are influenced by many genes, each with very small effects (Arnedo et al., 2015; International Schizophrenia Consortium, 2009).

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Consider how researchers have studied these issues with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Schizophrenia Is Inherited?

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Consider how researchers have studied these issues with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Schizophrenia Is Inherited?

As we have seen in so many different contexts, nature and nurture interact. Recall that epigenetic (literally “in addition to genetic”) factors influence whether or not genes will be expressed. Like hot water activating a tea bag, environmental factors such as viral infections, nutritional deprivation, and maternal stress can “turn on” the genes that put some of us at higher risk for this disorder. Identical twins’ differing histories in the womb and beyond explain why they may show differing gene expressions (Dempster et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2010). Our heredity and our life experiences work together. Neither hand claps alone.

For an 8-

For an 8-

Thanks to our expanding understanding of genetic and brain influences on maladies such as schizophrenia, the general public increasingly attributes psychiatric disorders to biological factors (Pescosolido et al., 2010).

* * *

Few of us can relate to the strange thoughts, perceptions, and behaviors of schizophrenia. Sometimes our thoughts jump around, but we rarely talk nonsensically. Occasionally we feel unjustly suspicious of someone, but we do not believe the world is plotting against us. Often our perceptions err, but rarely do we see or hear things that are not there. We feel regret after laughing at someone’s misfortune, but we rarely giggle in response to our own bad news. At times we just want to be alone, but we do not live in social isolation. However, millions of people around the world do talk strangely, suffer delusions, hear nonexistent voices, see things that are not there, laugh or cry at inappropriate times, or withdraw into private imaginary worlds. The quest to solve the cruel puzzle of schizophrenia continues, more vigorously than ever.

561

RETRIEVE IT

Question

A person with schizophrenia who has PsZo0R5Y8yrofAbHg+qqcQ== (positive/negative) symptoms may have an expressionless face and toneless voice. These symptoms are most common with yRohS0cZ6c+wyFeP (chronic/acute) schizophrenia and are not likely to respond to drug therapy. Those with sit38m8ttij34gi1Qyks6Q== (positive/negative) symptoms are likely to experience delusions and to be diagnosed with AJwV79uwptytJ1TY (chronic/acute) schizophrenia, which is much more likely to respond to drug therapy.

Question

KqtAKuT6wSw3KbZ7jMMuC+O5+6dqD6Iycuozdt4Fjh2cm8i93OVRNxLOh9S/u6ZausyAJbgOfQTyWngco9k9QIowmhvCw4CGPqBFNempdc08j6zeyLJDLXRTjSNqo3rakwUoR9HW5SbV0pyRCPqq7ahsAQY=Other Disorders

Dissociative Disorders

14-

dissociative disorders controversial, rare disorders in which conscious awareness becomes separated (dissociated) from previous memories, thoughts, and feelings.

Among the most bewildering disorders are the rare dissociative disorders, in which a person’s conscious awareness dissociates (separates) from painful memories, thoughts, and feelings. The result may be a fugue state, a sudden loss of memory or change in identity, often in response to an overwhelmingly stressful situation. Such was the case for one Vietnam veteran who was haunted by his comrades’ deaths, and who had left his World Trade Center office shortly before the 9/11 attack. Later, he disappeared. Six months later, when he was discovered in a Chicago homeless shelter, he reported no memory of his identity or family (Stone, 2006).

dissociative identity disorder (DID) a rare dissociative disorder in which a person exhibits two or more distinct and alternating personalities. Formerly called multiple personality disorder.

Dissociation itself is not so rare. Any one of us may have a fleeting sense of being unreal, of being separated from our body, of watching ourselves as if in a movie. A massive dissociation of self from ordinary consciousness occurs in dissociative identity disorder (DID), in which two or more distinct identities—

People diagnosed with DID (formerly called multiple personality disorder) are rarely violent. But cases have been reported of dissociations into a “good” and a “bad” (or aggressive) personality—

Speaking as Steve, Bianchi stated that he hated Ken because Ken was nice and that he (Steve), aided by a cousin, had murdered women. He also claimed Ken knew nothing about Steve’s existence and was innocent of the murders. Was Bianchi’s second personality a trick, simply a way of disavowing responsibility for his actions? Indeed, Bianchi—

UNDERSTANDING DISSOCIATIVE IDENTITY DISORDER Skeptics have raised serious concerns about DID. First, they find it suspicious that the disorder has such a short and localized history. Between 1930 and 1960, the number of North American DID diagnoses averaged 2 per decade. By the 1980s, when the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) contained the first formal code for this disorder, the number exploded to more than 20,000 (McHugh, 1995a). The average number of displayed personalities also mushroomed—

562

Second, note the skeptics, DID varies by culture. It is much less prevalent outside North America. In Britain, DID—

Third, skeptics have asked, could DID be an extension of our normal capacity for personality shifts? Nicholas Spanos (1986, 1994, 1996) asked college students to pretend they were accused murderers being examined by a psychiatrist. Given the same hypnotic treatment Bianchi received, most spontaneously expressed a second personality. This discovery made Spanos wonder: Are dissociative identities simply a more extreme version of the varied “selves” we normally present—

“Pretense may become reality.”

Chinese proverb

Other researchers and clinicians believe DID is a real disorder. They find support for this view in the distinct body and brain states associated with differing personalities (Putnam, 1991). People with DID exhibit heightened activity in brain areas linked with the control and inhibition of traumatic memories (Elzinga et al., 2007). Abnormal brain anatomy can also accompany DID. Brain scans show shrinkage in areas that aid memory and detection of threat (Vermetten et al., 2006).

“Though this be madness, yet there is method in ’t.”

William Shakespeare, Hamlet, 1600

Both the psychodynamic and learning perspectives have interpreted DID symptoms as ways of coping with anxiety. Some psychodynamic theorists see them as defenses against the anxiety caused by unacceptable impulses. In this view, a second personality could allow the discharge of forbidden impulses. Learning theorists see dissociative disorders as behaviors reinforced by anxiety reduction.

Some clinicians include dissociative disorders under the umbrella of posttraumatic stress disorder. In this view, DID is a natural, protective response to traumatic experiences during childhood (Putnam, 1995; Spiegel, 2008). Many DID patients recall being physically, sexually, or emotionally abused as children (Gleaves, 1996; Lilienfeld et al., 1999). In one study of 12 murderers diagnosed with DID, 11 had suffered severe abuse, even torture, in childhood (Lewis et al., 1997). One had been set afire by his parents. Another had been used in child pornography and was scarred from being made to sit on a stove burner. Some critics wonder, however, whether vivid imagination or therapist suggestion contributed to such recollections (Kihlstrom, 2005).

So the debate continues. On one side are those who believe multiple personalities are the desperate efforts of people trying to detach from a horrific existence. On the other are skeptics who think DID is constructed out of the therapist-

563

RETRIEVE IT

Question

1ubGb9dUVaS9Kr8Gl+JktREwFV3wkHk2w9j7y5w6iwwjmd2JDvsY0OSd/dkjiOTlVVhnm0LkOU81FlFUoCKugVemg35vCnOJCaRCJCybuqqMqOHpkMZLnayNNDBt5oh0gZhnTnNybsITZNMIwqBQ+88NpQ48sJnyV7wLMxy4YWtsLfjcAgcFJUk4TAGbhLQMd5dvz74mug+9q9Qj34UcJobnTCvbVa9r5ppUQEtJkH1tA3eO1vhv8IwARj25qSAPBHlUyZYkrk3o9/DC0+WfyA==Personality Disorders

14-

personality disorders inflexible and enduring behavior patterns that impair social functioning.

The disruptive, inflexible, and enduring behavior patterns of personality disorders interfere with social functioning. These disorders tend to form three clusters, characterized by

anxiety, such as a fearful sensitivity to rejection that predisposes the withdrawn avoidant personality disorder.

eccentric or odd behaviors, such as the emotionless disengagement of schizotypal personality disorder.

dramatic or impulsive behaviors, such as the attention-

getting borderline personality disorder, the self- focused and self- inflating narcissistic personality disorder, and— what we next discuss as an in- depth example— the callous, and sometimes dangerous, antisocial personality disorder.

antisocial personality disorder a personality disorder in which a person (usually a man) exhibits a lack of conscience for wrongdoing, even toward friends and family members; may be aggressive and ruthless or a clever con artist.

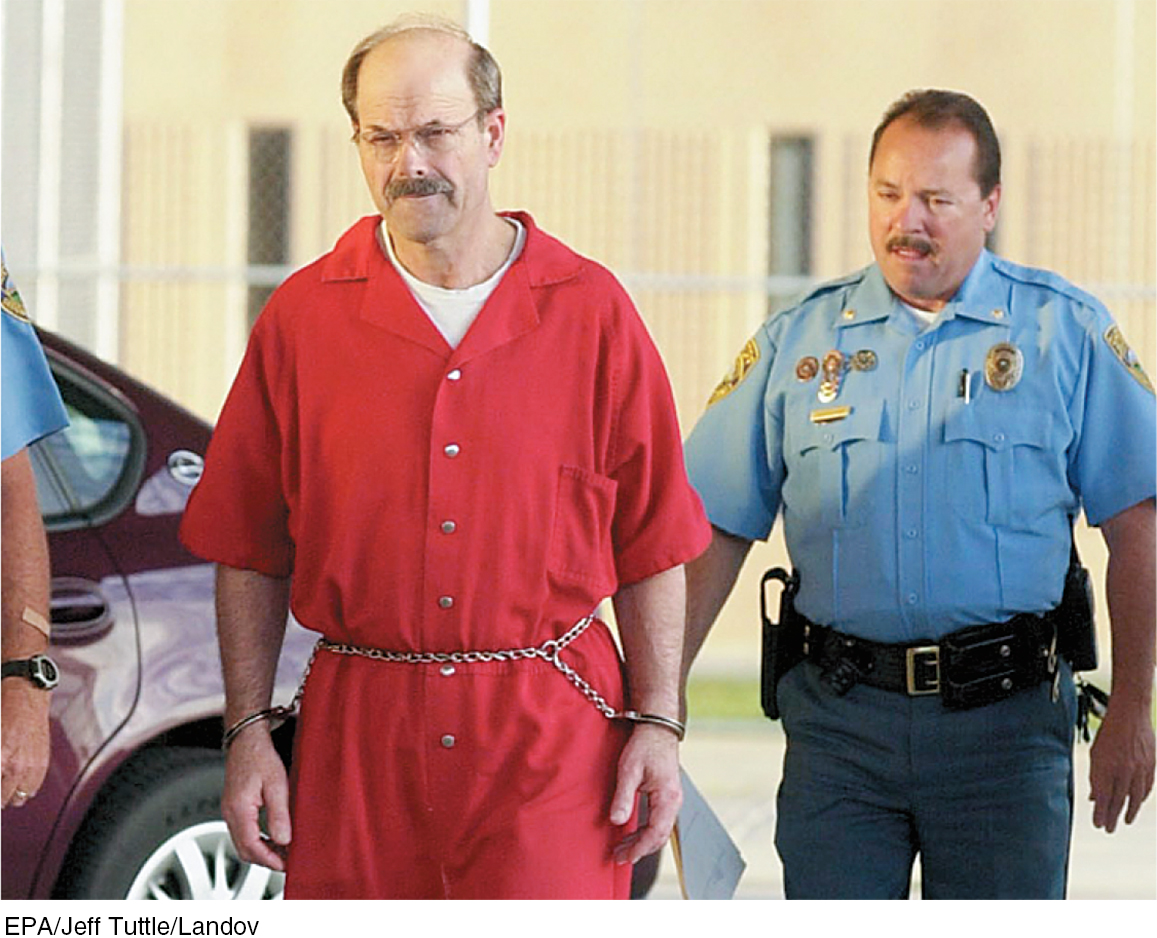

ANTISOCIAL PERSONALITY DISORDER A person with antisocial personality disorder is typically a male whose lack of conscience becomes plain before age 15, as he begins to lie, steal, fight, or display unrestrained sexual behavior (Cale & Lilienfeld, 2002). About half of such children become antisocial adults—

Antisocial personalities behave impulsively, and then feel and fear little (Fowles & Dindo, 2009). Their impulsivity can have violent, horrifying consequences (Camp et al., 2013). Consider the case of Henry Lee Lucas. He killed his first victim when he was 13. He felt little regret then or later. He confessed that, during his 32 years of crime, he had brutally beaten, suffocated, stabbed, shot, or mutilated some 360 women, men, and children. For the last six years of his reign of terror, Lucas teamed with Ottis Elwood Toole, who reportedly slaughtered about 50 people he “didn’t think was worth living anyhow” (Darrach & Norris, 1984).

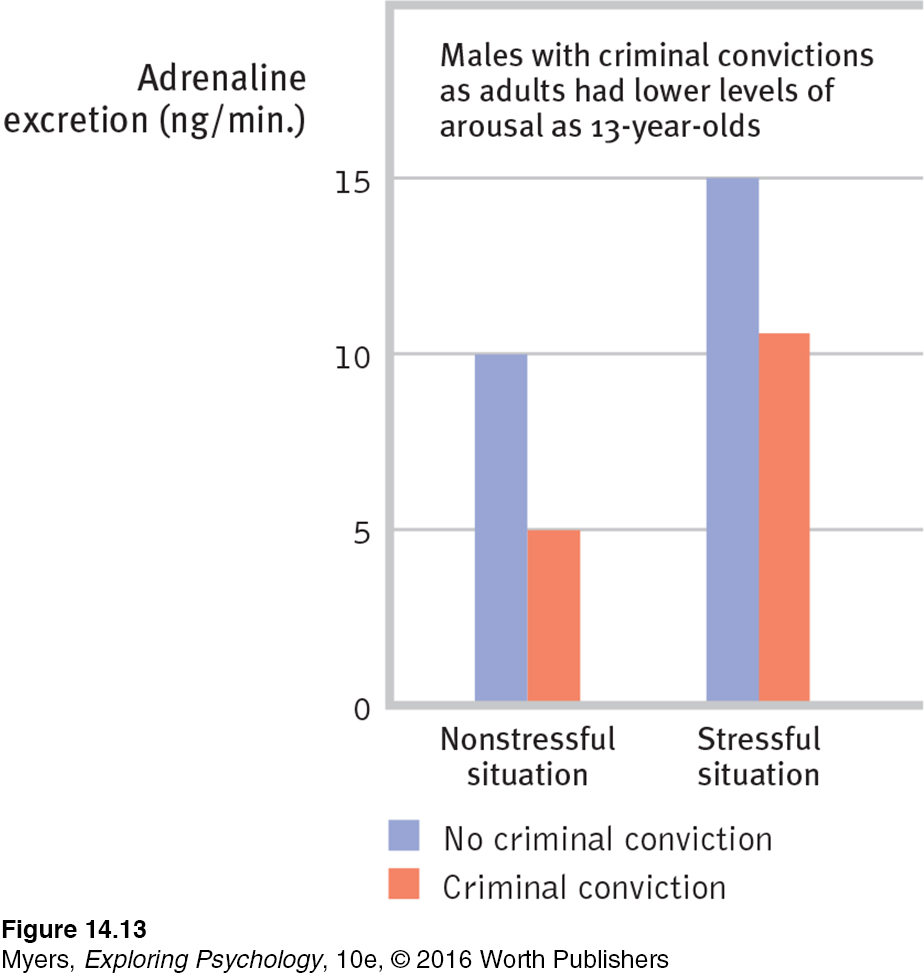

UNDERSTANDING ANTISOCIAL PERSONALITY DISORDER Antisocial personality disorder is woven of both biological and psychological strands. Twin and adoption studies reveal that biological relatives of people with antisocial and unemotional tendencies are at increased risk for antisocial behavior (Frisell et al., 2012; Tuvblad et al., 2011). No single gene codes for a complex behavior such as crime. Molecular geneticists have, however, identified some specific genes that are more common in those with antisocial personality disorder (Gunter et al., 2010). There may be a genetic predisposition toward a fearless and uninhibited life. The genes that put people at risk for antisocial behavior also increase the risk for substance use disorder, which helps explain why these disorders often appear in combination (Dick, 2007).

564

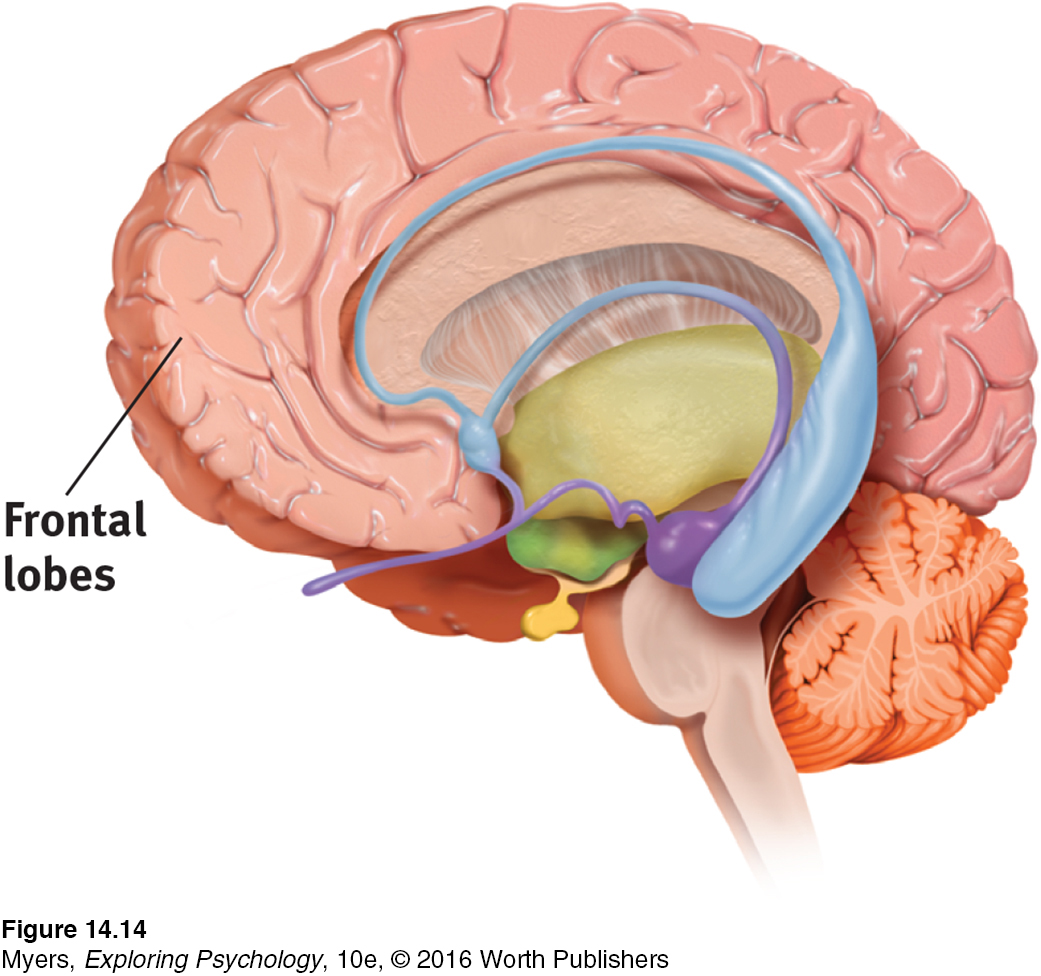

Genetic influences, often in combination with negative environmental factors such as childhood abuse, family instability, or poverty, help wire the brain (Dodge, 2009). In people with antisocial criminal tendencies, the emotion-

Does a full Moon trigger “madness” in some people? James Rotton and I. W. Kelly (1985) examined data from 37 studies that related lunar phase to crime, homicides, crisis calls, and mental hospital admissions. Their conclusion: There is virtually no evidence of “Moon madness.” Nor does lunar phase correlate with suicides, assaults, emergency room visits, or traffic disasters (Martin et al., 1992; Raison et al., 1999).

Traits such as fearlessness and dominance can be adaptive. If channeled in more productive directions, fearlessness may lead to athletic stardom, adventurism, or courageous heroism (Poulton & Milne, 2002; Smith et al., 2013). One analysis of 42 American presidents showed that they scored higher than the general population on such traits as fearlessness and dominance (Lilienfeld et al., 2012). Lacking a sense of social responsibility, the same disposition may produce a cool con artist or killer (Lykken, 1995).

With antisocial behavior, as with so much else, nature and nurture interact and the biopsychosocial perspective helps us understand the whole story. To explore the neural basis of antisocial personality disorder, scientists are trying to identify brain activity differences in antisocial criminals. Shown emotionally evocative photographs, such as a man holding a knife to a woman’s throat, criminals with antisocial personality disorder display blunted heart rate and perspiration responses, and less activity in brain areas that typically respond to emotional stimuli (Harenski et al., 2010; Kiehl & Buckholtz, 2010). They also have a larger and hyper-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

w3QT6O8IKskiNTURvGFMeDvvLfvI1OR443KzeHh42Ad8vwhltQwtTIkXxxAdw0/saxCKSaYT1nJr2PLurkc37eh4vRYuywKr8xJxplWN/6qlJ8oxwRG5DpyYZtionIqLaDtSd0WaHX2TnBAD4SD3s2xbm0RZy0+XPiiNBqO2aDGkqef0KKXb7w==565

Eating Disorders

14-

Our bodies are naturally disposed to maintain a steady weight, including stored energy reserves for times when food becomes unavailable. But sometimes psychological influences overwhelm biological wisdom. This becomes painfully clear in three eating disorders:

anorexia nervosa an eating disorder in which a person (usually an adolescent female) maintains a starvation diet despite being significantly underweight; sometimes accompanied by excessive exercise.

bulimia nervosa an eating disorder in which a person alternates binge eating (usually of high-

binge-eating disorder significant binge-

Anorexia nervosa typically begins as a weight-

loss diet. People with anorexia— usually adolescents and 9 out of 10 times females— drop significantly below normal weight. Yet they feel fat, fear being fat, diet obsessively, and sometimes exercise excessively. About half of those with anorexia display a binge- purge- depression cycle. Bulimia nervosa, unlike anorexia, is marked by weight fluctuations within or above normal ranges. This makes the condition easy to hide. Bulimia may also be triggered by a weight-

loss diet, broken by gorging on forbidden foods. In a cycle of repeating episodes, people with this disorder— mostly women in their late teens or early twenties— alternate binge eating and purging (through vomiting or laxative use) (Wonderlich et al., 2007). Fasting or excessive exercise may follow. Preoccupied with food (craving sweets and high- fat foods), and fearful of becoming overweight, binge- purge eaters experience bouts of depression, guilt, and anxiety during and following binges (Hinz & Williamson, 1987; Johnson et al., 2002). Those with binge-eating disorder engage in significant bouts of overeating, followed by remorse. But they do not purge, fast, or exercise excessively, and thus may be overweight.

A U.S. National Institute of Mental Health-

UNDERSTANDING EATING DISORDERS Eating disorders are not (as some have speculated) a telltale sign of childhood sexual abuse (Smolak & Murnen, 2002; Stice, 2002). The family environment may influence eating disorders in other ways, however. For example, anorexia patients’ families tend to be competitive, high achieving, and protective (Berg et al., 2014; Pate et al., 1992; Yates, 1989, 1990). Those with eating disorders often have low self-

Heredity also matters. Identical twins share these disorders more often than fraternal twins do (Culbert et al., 2009; Klump et al., 2009; Root et al., 2010). Scientists are now searching for culprit genes, which may influence the body’s available serotonin and estrogen (Klump & Culbert, 2007). Data from 15 studies indicate that having a gene that reduces available serotonin adds 30 percent to a person’s risk of anorexia or bulimia (Calati et al., 2011).

566

But eating disorders also have cultural and gender components. Ideal shapes vary across culture and time. In impoverished countries—

Those most vulnerable to eating disorders are also those (usually women or gay men) who most idealize thinness and have the greatest body dissatisfaction (Feldman & Meyer, 2010; Kane, 2010; Stice et al., 2010). Should it surprise us, then, that when women view real and doctored images of unnaturally thin models and celebrities, they often feel ashamed, depressed, and dissatisfied with their own bodies—

“Why do women have such low self-

Dave Barry, 1999

There is, however, more to body dissatisfaction and anorexia than media effects (Ferguson et al., 2011). Peer influences, such as teasing, also matter. Nevertheless, the sickness of today’s eating disorders stems in part from today’s weight-

If cultural learning contributes to eating behavior, then might prevention programs increase acceptance of one’s body? Reviews of prevention studies answer Yes. They seem especially effective if the programs are interactive and focused on girls over age 15 (Beintner et al., 2012; Stice et al., 2007; Vocks et al., 2010).

* * *

The bewilderment, fear, and sorrow caused by psychological disorders are real. But as our next topic—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

People with GwurflziaLGo7HZXs96biCmF+FXCkmLY (anorexia nervosa/bulimia nervosa) continue to want to lose weight even when they are underweight. Those with by6iUXsni0tS4+PPMn97kfBns5k= (anorexia nervosa/bulimia nervosa) tend to have weight that fluctuates within or above normal ranges.

REVIEW Schizophrenia and Other Disorders

567

Learning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

dqhmkUVD5Fd7hyGnfqEgQpv9unIH2ICY5TuIvgI2Plx6unKr/b5ApJyZzbBwaPkOhzKkN6MR0OKa2l0YSrGaKoP1ZRMXuftE1I8nLOC/G/k2JifWLkLh4oA2QTS7rz7QAGJelCUhWkiA7fATaJfVD++IQi0m16W8BLR3Ss3olHw7hTr5ufaML+KTfw8EDMbtNdTupuiEtL/Rlhx1qUTapg2r33u2s8BUV4YBjkqQI/3bCcp6SVNLqXpS5h6HSpm4xES38A==Question

YrqUp1AGDABX+4RTQgC0DxuBu6ckU9SO+5ic4b2ArzUr3xhoWfJ8DyGjPZ4qCXRTjctwnz0pzHVQm75ddgjUOVGanc9Wp+zfalRg/AFjy2Gph9dD9iOwHP9Xqdd5hPGANFyZ0M1in5Hj1+PvyVivMMBRgWm+bzH7yybijclml9bTxwI7xLB8D1eP0puJZ1+XmdbSJjuhUCaxzTFt4r1GshyzEbPo3gVexsZFCgYced7+92oGQuestion

52bIgGN4MNMXILyH5gORAh8fMcXTXzhPHomGzFWtLH5vj3B/VhYKeq6tIBu7dk/jzuf9C8oElTldVN5NYEkt4/pVa/VQUfA52wVqc3+6rLBsFSTZOvfD3PuCRfEEAB/6S99lyuDB4SuPi1vlNIIHU/audNvaeESk0BtP1Tpfa1gLrrJR+s3qUz7a/5Y6ssZAHuqmG/Nled36/dMGGa7l5pv46XRLbsZ4QRzYw8MSkHM=Question

dNxuXY+BqH5v6teUW/H7Eg5wm0tOseNqRqscM+qEdMUrHRry9pceYIRiOF1TAyVRrFZGjRLdzRP+UMPRKHGy1hPCowFJcVPRT9N4xEzjHBc4vm8CyW3ooYJe4yPpJHggwdhnOhsEGsd2rJG5h/pSQWm3cRQMbyMpZlCk2cb7nMJikozm0Z/jortDFF4tqWk+f0FEqXuB7fIr87gr53Kd4i+Pwm2/jishjrslhoGmPgXTDQ4Jn4bYlxLuO9EyWjnlEk+tA2xoyGI=Question

tSmLPz38Er/OdfNsL1+b9RwY/EXQjUf1rvT6e5y3RgS/SgNDRuA26TjncWtuzjVR48xyz0ixz0rtAd3DJnqFeS9MjpIZdX9afONJgJTZtGhhULStpXKztJ3EouUQNvTad6XBs6NChBM1b9wTAj91BSA75sJth8VM8zz/PbbjRYVWy8NwewZ6kExhOKLaTMtUahPT7ExRXdoqD6gZQuestion

u4q9UjYyGBEVK8c535CP1O3qedGkzyVY6meR6oRL+UBGVJqPCmKXcKz+w5x4DEWNVa8chS+3qWIwm1hoUU8rh135VIA88WcB9yhswOW5q7tufP3WVlWalU/WkGb3aKM9CihAi0C8eSfeG5NqhCIQIbWzW7Hldz+NcaXKEjqeFcM8MXUzHy5iqh7o/Ql0F4MozHih4+BZWET+C+myIDfVRfT91iSQKd+CwGsB5/dk6PS2fWMtQuestion

gY63WUhAR3/JR5gJ2jzeuvNKUHgmviMCIOmWe/TsEMJEB52Euh2BaxHVcMiRfBPdVk8L01qwzRHZXvAqRr1XfXYcc4lIrpfguv+Rn5mYiP84+yJaKpIxGUFFlzREE7rPxBzLf6elmnwO6VO4hmQi+CkcIFa1tT4HJWhiLUmWw6VAK/eiO6KpeJeVJo2DDpBUAtDdP3YLlPXqKNOV/q3R+pXirGBCuY4PWhjmBwSFDcKkWIe/3LXcwo1zDiQNkXfaPV7a0RRXYHNoMGkfXgtDmpNXn1LF4CH5iXeHaRaM/gL9dLh7I3hvkF+jLyIEo/H4LSpEjw==Question

OazAHsmPQw/koIPJh+9rTwCMeOBbIggJmjcn0EPP6lYKddvc8c7WfeqNojxurjUvvg3iFTZNY4e4Q+a87Ps0OfwZbra/1ivYR6IyhdLfGH2VvD9sH6FgdhgOlBxDiZknyLcge4vld5jV5cJyz0MrhAg/1fZGflejF1gg9ARgmS7Mm6M6Rziu+FGmQKlawti88fw1T6FTZKvIFqIybXhkal4erVsf8iG+H6BZnt22L1rof7QQPjU/3/pF/qFry4pVcGZj2f09Ayv0QQo9CEIdzp2Y08LphiLcd1BtS4N15fItNwrp5/Bhl8ypXFQ9uCQAuxTs/lAT6CSg3NOrNpUDWUXp7SXTS85X0wZpPZu2Lx0qqyitY3Yo8HG09Wgei/Hn4MQ1irgRREyvnc+mhNizT28+JLKWwr4BTerms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

AEdn7P6ZckOaompRtRGYtAFnRRjJX82xvXN671wCoV3/QHRMycK7kBYCrljrYyWFXCBP+MQA9Lhp2c3f/b7oHUXhe7nPpIy/++PIWGVG2EdtNHc2zLR24Ftr1KsBYmEnsS+pa5DCNY6C5EbkD54oDxVMl3f3nGrIdqCPAfCNjth6YOjH4iR67jGOZDh7MtvEBwDZ2oSvtaym2COebSXB/4OYm4wG88Rc8MG0SDwABzW9M1OfJaGHQEuvFBoDsjQZJO2Gxr+Nx5DZpNfXgj7XAqGcjU+vpqmXMHIHkDjYTg/hEIK1QGnDFuA72LpH6pXtiqAxIhNldgYeUtiCGCKUTpUUUc5v2JdKlai77uFYQBwa6s6PFj+AG4XJ5SIA0ZHol4aK27qcu2ze6M0vQXg/GFr2QKG2ek0vmThakQZA47JfJbR3WUp0r/F/OkGYzVO/DxmAcJnoq6N7fHkGLaYbUhLukMlHr/H3zBZzmm8THjQoOV8xL5cGNkdNDT+RGw6X+zXMkxxA/SNrampdr7ltgFcAZJp7OaHKSDXM7J3M8Mz4CKZALUgOifGLHaQIRTHdm970NkJNGQvT9MxSbGaPye1xGc2G0g7CxaIvUU+yxErIt9B4wkZfQi/EJyT0MyOvs0okQxE9K6ANIscGfRS34JUx0rs8Mo43ro61q8GE38XkjgPOBbV54z6UIIdlS0m++3wJuWcohMt/jzFMbdtQEjOdQ0gX+WAbVtWWwzxGyweVg+UaRBdt2LzVP82zIqisyr9rPKo8BgU1ZE1mxPMdqY8mDTvbFEWd1L+k0C+EvuhpBAjKpa3G/LuTgD3L+N2Ut+r/9hgBrzgfDaw9g8ufV5GYThLP9pTztXCmXpQ8sUNwvs4ul8KHtUgCrpgSYK2BBUGC2oqgIh2xcI+hm59FMYG/gqBXc7Bdzuyn3W+UDmzl/FM8mvBlnQ5s1mQ2jL4EqnlymdcvCoy59XBEon9wTnC9OWCTTK5vcDjPFwEVxWrCD5maCcQY8hcnax70knHt7C9YTJFgDVoA4IPTQnx4y7Rj/F3UY2JXls7byyUISdupuZITAt092tk3qOaQVq8qCHyk5nSnejHi0RIYxNtgAODxTH8YlfAoUjeqAxgSIFraPSTPpMcY2/GKosjuEnZ7mDaLImviBAHhbeV1Y8rngfFzOCpBDYPzcCFZnLID5uKPvqCleApo1rFzfcawnZZCEgSNzOVDr3TjYFOaxoWD0foA9fXnve0PS57DjYlR2WTaWKwgyFH21EfDoVKNl41IkFjhjM9E4nwikzavhsHVn6cNY6e4RsYfwLW7SKxPXW0BHuaeUT033Uw6aq1xUvHFiYss9jWFoJLN21xbQrLnS/g9HGUG0XRmLx64Mq0XDZK9y0u4YAirAsgCFnUPmWNtpn/j2lenhMruU5/vLpmnAZet9tvwE7XMH65CEXe2BRwNEv4l4JFYnsApUC3Iv2stTZUWppoMDTXj1sL+o6q3RW51MqRW1OsJAHWuStYOXo2k7NMVOA8PS+vBCuIoRrnOq05LnReyKbSPjtytwee1DRJZ4l9tukAPgID57NUhqf6WFqwmcY2T8dUJFgAntoQs9yswTy7WdosJUFpF0Eq/5C0inBABNA6AX9CdYKn2KI67LgYVIRWeV48MVbWggJBpeIWEDMwNSNPwFwLOiK6ptEPtujlqFieiTSdK23fVZn9PRSnvPrDG4Q+CxSXJQRXObjSuTmVQThAbqh7x142mu9ICeKzSafs5tmyGvkREIudKtw4xiByqRsXQJ5L6TqHBfl1dskunPGFalKM/oPUkQ+VtWOE4IOD/WIdpzztv85qWRT9yEtrivE39BkjFPt1ZOoCWQPy4mdS+mZ64jchh6B2CIlFrs5fkIweXR97t6hdhgpqb5hEe9HEvejdjKdc5fq8/OC+OUNsg1TxLOpfhLG+S9KC5gOlICNcsS9bDXWxvtXabXslcUas4ddl3J7PLH2q8cLeiidrpefi5slzj0I5QX+k1LK6tm6eS7xSpnr3qFcwJkFdIcmo4EVbqJyYffjPa94ifLQ3IGopnAG+h9QOKEDdwagKmBxEjfA7teWe4wuyavkt3at3yuFPCsmh/z5lWfwLs086l/ByBlGkFOq2biHG2lJSYIR1Q0R6G3wGy7b8va3nvSD1zRZLyyBJiM6zKri8bD4yQ/oHOl5Nq0z3F0bCZv2c4aoIbre/83Q1jwgu45gaf+xRp56vEDD/fO3ixbltdzr7RAX4iDsEs9NQBuJhY/zVzAuVUHEfA0yfGcHWwM/r8K27iBPEIsvJz3OIK9F2DNeLkHmgUc6u8CakMuLnEzShtrwSorshD6b4eHQuBtoteJeKf6LlH64xHd6IIVQowM9x+68pJFZpiIxceiJ8JknNM6UDkNMD/ScBG+ezIhjDgGUVEE+ZoDUHHjapACHxNCWyCxN7RmxSWWgRL/gnQGOd9N7WHJsURb3L6oUKIgMUx4ZdHCUgn9wPgAJxoe/qePZsutC7eUSQmCwJKaobE/aan6q9NI3zpSr1nYmXF80VgHGJSEmNlIPUEM8vaoskPkOXcJzJ4t7QKriMO7b5zeQzTr3Md1gwMEClFLc027LkIFh3D6Z+q/bYIf1VLZRlUJ+hSREroOba8mm0ye5kjvoCtiMEJquvnxdaY0rp73JSWrpCjQGcXzz3A6lYEPDYW3GVGg+bHS1eOnq7kJPDclKSBb6Mkklrsh1YSHSRO1WiyNCv46TtKr+d7dHSNi7J9qpK/mI8cFxXGDGQdzjOe1tL2Sa9fprY5CCcd+3GjCGZPdsyLEb/3BWNq5JZQGmQa7PTz/03cs828lt5xY/47ht6Z2EQYg+2R4N5F2QbjHFrKZiN2xho8hqRKiEM1y51OjtwcqSsiOwL/7D+estdMqk2Gu/qT5ZcuM7dqccfLgxg/xZqdWx04sMtarxHe/INkIKQ4fIja/El+cuvgRZMkACKjXcZNtVSJDYTLeOQZAaYnyQrTL7PshcKPrGHlEoPFarYSaYx1IDgDhaBWSuQF9Q9CP4xmcNU75p1onudY4T277d+GgVISIdAXXKrWxAKfiT3P466tlh7wZJiOoGJd7B4j6yvxmxTvwZGip/T88Mumt+tYMjvOPnXxPjqau1eruUUimR83JIMxpet0w4zFml1OWH5t7gQpGAxtpZIV1vujaM9h1yg=Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 14.17

91dK/F4grJTV0Vgo68YHOOEsa8Hpkp73/ngMxyy60bqZZcANqKrypr/777uSWejzrG6s3yq7zEnVnEjBmYnURB2tKqte6YPjxesvTrqIy0vzhZsDw/Lhm5YFACX8+rpY8T9SrREyCRqumG8OuM6WzhGJWLPRs1yEpEPtomwW8lcOHSEXeo5wlZPc8A8fuUbpgO+d3LtXlfQjFMYD6oxVY3DTutd9tJluklMHbhf5zs04TZ8GdZa9RWY5ymgbWXZHNwW7JqdCd3DSk2ZkU6TrUs146NhnYShL68sCihyQMAF8MswM7vRuDmBrvVrSrxN69zCdhUsuwvI4schjQuestion 14.18

90KkQPNYtJUhertPM5VQW/SH/Agkd0+ErRlkdxpyXDguvE9Jd24UEb41Q+rqI/O9T0i0YxcMm4eZu7jaUqcOZiN3+EjV8RvC+hzUibf0sdQ8e+NgnhI4ZVNtUQi/YslMMY15oLL6LOx6v0UBLtWUcI6DHaiaMeDEfn7HbAbs5F4i3ydwEXeemCszZ6vuAlIIlurdxHpbWKqHmcOJa+7RgCWGRQ43LdUxc8xEOzHy9LDD+F/NyDnTKye6Ev4=Question 14.19

3. People with schizophrenia may hear voices urging self-

Question 14.20

DlOz4LErYP6o0PEeUn7rz8kd+cEydNO9zjeT9m8fCG5+Kea0zLRLWVy9HySGo2Wny9kCcEWm5OovKmjxZqdWZL0CxBxl+K5hwe5weV+Qp9o+sULwwMUoqQBLH2DhKi7e/0nmRR/xwwRpsgMsVTJdk4jFxkpUPNb51AcvbzsfBN2Eou+C2x0mSUipFjQ6jhxvBGxA8tgJ/FzcUzm30QHzuaqdwsWU9nuDG6iFKNYJoxJQ+nqt21YD3MBKSpaZrdYv7lESAi7BjODeY5Zy3248vGzHlPjvCAXeIazajVQpknVxqSfA6BQBdtVgrkmNNcVSlfYmhQY2ynCEGtQo4tfhWooRw3vXkFLzhlb0Pezq5bRn949yoP8kchhO3dxX2ZZnocxNQg==Question 14.21

7B78jphnivUcTHguG929iVxXZ4QIcYkTY9uit7bavIIDsPWPt17LFk1UtIedFdW3oFJhY3JaXekYXRuPCrmr3lpfsM54QX0isVfeo0RsnBKWS3Wt3lThrsRK4koTOdDBNt/DYolsw4uDjgMOmQpvnqjlVmd3MVSn8jCzJSB2sFyM2/okEhOZn72xKe665SSqqcA5fUGRVSJASP4FoQSxN1e422Q2c3OoHFUOY402Qv0oeUvkuiyTJkraSLUOtfcT3LSLLvtenOZ+gKp0mKIbk0G2olS7Pl9nSkGyj4L4gS7kgIZBXu6Rxs+0n5F2hxdVbS+SZMvnOqdqelwlocfZ72MJ4H7Orhxb9avKOkein9TIZiZGb/TkM+D3RYRXEK7OyokMM29v7vi7M7xm6u8muxQ+6NV8r3RTvMEN35fInoYOmScJH0IsDv0pUsE=Question 14.22

KuBgAk7EHurpMKUfgW/XG379ZL3liEruHAvdBG7u+L198bHfQJZjIiQcfVBUeE3OdIkEorWG4072NRkF0CYsYi4gxMZjQrdZdmPxBWOp61nTuiVgN6KR5m6EQl788Mn9ksZMcTKxkgMKzK2i/vuJaius86jN5PXZzRjYIIxNzDiTtQLkkRQyHRAF5vdKBUOa2Ys8K1w3a4btiBGWa+xug0aD+htVtb1JsjRWwGmGfwIA5bZBp4Q8JeieEZPqoerSxM8Am3xxA/i/winF0eTa7nMBFFiqOyLIAsoo3Z0E/WlAXQ8ekWA0fdWCriwu6JmBZC6+sLksAwB/GdbVXfD6CdGKtumiGnh1bdHkrP6QMtQcySYZAhldPuKrBC/+K42EBk2rJtbB0Zo=Question 14.23

tAu5F2XQvvLc4e04ZxsJu25aCvSZda4F4v2j2DLUsnhhjR9pXogcBEU65OEp+olh0K3TvqpyQj5IIPoz75kNIlIMfqiTIpXB2IBL7Nj9+brFkHD8Q4XD9Q6ah9/nSUVWZOK449psmCm2HYUbwKGIIjOVmujM6RSagEJsAAlb3DYMs4BvCXRwXFNNnnFRG5XU50IpcWtu7XBtUrqx3Wdm1wHwlHoeJLNP4hIpRSyZWmnHC3c/k5hRYlH56Spx4D6Gin35FVXdwypwwgQb5oJc2YTdVQ5NoGEoFkdgi1q4S0+WdWIGVaBd29KsxaD0Qig3FZaw4K1COHc03nR36G+F8tLTuYPCq8Q823ReRonnWwD5KyhjWhdoE01ojp//dtpjSzcFGxUDFmPYq9a3UZ6JNRwWbtN2Fwd7ZG3NSzXEFYjnp/f0okp0fTOItxIiBt/j2chLpEt6biCsKr3fbkhO7N1VENa/N8BOdoGjHeTxXfomky8Xz8JubCjrB1VJz/HM3XAEU/oo5Ko=Question 14.24

Le717qM6m2XXhdv5tw7zyUIsbsjxcpbkcINFmY6vT3kBNW0y87VbUfBMIiVFSvsFm5+zJBmARPByrCKuLnM1oL/L8iksuC/NurmnKF0rTBVPSrSbAzTSeak/r3P2xXAI3d2Ntu0ruA6A8E2QykSAP8xFXL7ki/nr+zV/hw0T5dbTCnMzWwHPXlOmpOtoZnz2gx2KBOglgsCbN8ncnWWKR6EyOaDEdJM5c7hKD+hSDsCyC3IbkwQhZvKQwJaKqo25Fv1eDCPp998+u9wj8LOVIEscOND9qFldUFOJ67rmZ9aqXqsGZv+/tO1lXraX+mta63HCS0NscO9mN/yAoi6IGlUoGFWisbkhMLM9OIFQuPinUQSjBuqqHqhQy0YT+XA34BuyykQLrgxFi5jDIRfckaVCvcnPbUVoCBgcruxBlCzxFLqSCTxM3+M1RG5Lj/rBiWdiRkN7MF33mpaKc9jUgdiOuo8SxW3n9ULgKYQ7UcH9eMQ2QuOzESpgjLeQ1tA0pZNZHbA/B9Rn86hlRcxqeH0XoTv87Lz/05R6OpO3g4qlUlksRScUqBKkk/xh7NkHFZfYyqZGUIPJtNGDiKD/62R88TYinoRqshNyvyoLrBXCdlVKTwRvg2I6fio/XgZdHUUeG2aqyR3Y6B114xymEw5Sp1bxx9rrst2/pHMgM1eKHES9h5/Dqn9y/8kC2RTqhx/ESZciJAseJU1+kioxcb8q2KLuuYXnCmmrd29hNltqQy0Dq36bincKvmHt+pOk9gkAZQeIC/9T4entLVPTix7M1fgfLYYcqTKfBgsAMBGvGFz91E3uqO8ttVJw2ZdGmOBP75F118JL5Ah9bYnd3A==Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.