Although in some ways we outsmart the smartest computers, our intuition often goes awry. To err is human. Enter psychological science. With its procedures for gathering and sifting evidence, science restrains error. As we familiarize ourselves with psychology’s strategies and incorporate its underlying principles into our daily thinking, we can think smarter. Psychologists use the science of behavior and mental processes to better understand why people think, feel, and act as they do.

The Need for Psychological Science

What About Intuition and Common Sense?

15

1-

intuition an effortless, immediate, automatic feeling or thought, as contrasted with explicit, conscious reasoning.

Some people suppose that psychology merely documents and dresses in jargon what people already know: “You get paid for using fancy methods to prove what my grandmother knows?” Others place their faith in human intuition: “Buried deep within each and every one of us, there is an instinctive, heart-

So, are we smart to listen to the whispers of our inner wisdom, to simply trust “the force within”? Or should we more often be subjecting our intuitive hunches to skeptical scrutiny?

This much seems certain: We often underestimate intuition’s perils. My [DM’s] geographical intuition tells me that Reno is east of Los Angeles, that Rome is south of New York, that Atlanta is east of Detroit. But I am wrong, wrong, and wrong. As novelist Madeleine L’Engle observed, “The naked intellect is an extraordinarily inaccurate instrument” (1973). Three phenomena—

“Those who trust in their own wits are fools.”

Proverbs 28:26

“Life is lived forwards, but understood backwards.”

Philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, 1813-

DID WE KNOW IT ALL ALONG? HINDSIGHT BIAS Consider how easy it is to draw the bull’s-

“Anything seems commonplace, once explained.”

Dr. Watson to Sherlock Holmes

hindsight bias the tendency to believe, after learning an outcome, that one would have foreseen it. (Also known as the I-

This hindsight bias (also known as the I-

Tell the second group the opposite: “Psychologists have found that separation strengthens romantic attraction. As the saying goes, ‘Absence makes the heart grow fonder.’” People given this untrue result can also easily imagine it, and most will also see it as unsurprising. When opposite findings both seem like common sense, there is a problem.

Such errors in our recollections and explanations show why we need psychological research. Just asking people how and why they felt or acted as they did can sometimes be misleading—

More than 800 scholarly papers have shown hindsight bias in people young and old from across the world (Roese & Vohs, 2012). Nevertheless, Grandma’s intuition is often right. As Yogi Berra once said, “You can observe a lot by watching.” (We have Berra to thank for other gems, such as “Nobody ever comes here—

16

OVERCONFIDENCE We humans tend to think we know more than we do. Asked how sure we are of our answers to factual questions (Is Boston north or south of Paris?), we tend to be more confident than correct.2 Or consider these three anagrams, which Richard Goranson (1978) asked people to unscramble:

| WREAT |

|

WATER |

| ETRYN |

|

ENTRY |

| GRABE |

|

BARGE |

About how many seconds do you think it would have taken you to unscramble each of these? Knowing the answers tends to make us overconfident. (Surely the solution would take only 10 seconds or so.) In reality, the average problem solver spends 3 minutes, as you also might, given a similar anagram without the solution: OCHSA.3

Overconfidence in history:

“We don’t like their sound. Groups of guitars are on their way out.”

Decca Records, in turning down a recording contract with the Beatles in 1962

Are we any better at predicting social behavior? Psychologist Philip Tetlock (1998, 2005) collected more than 27,000 expert predictions of world events, such as the future of South Africa or whether Quebec would separate from Canada. His repeated finding: These predictions, which experts made with 80 percent confidence on average, were right less than 40 percent of the time. Nevertheless, even those who erred maintained their confidence by noting they were “almost right”: “The Québécois separatists almost won the secessionist referendum.”

“Computers in the future may weigh no more than 1.5 tons.”

Popular Mechanics, 1949

RETRIEVE IT

Question

/93OD7+cIv8jNMIKKRig4b1fPMEvjgVzWNXxb/20u4Mx5MdsksUgMI9bbKr1sHsQLvOeg65iPFQXgYmCXrtDPzQ41QMC5pP0UNM1waIR0nvxMF5qipFyhGyXiPbZEf81g3pS9NjB0DJ7y2fC7Y56FGtfhqkBTNlyoBdrp5sbeh7R2ldSmixV5J+3qqD4RGQ+WTEXYSx10Z8=“They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.”

General John Sedgwick just before being killed during a U.S. Civil War battle, 1864

“The telephone may be appropriate for our American cousins, but not here, because we have an adequate supply of messenger boys.”

British expert group evaluating the invention of the telephone

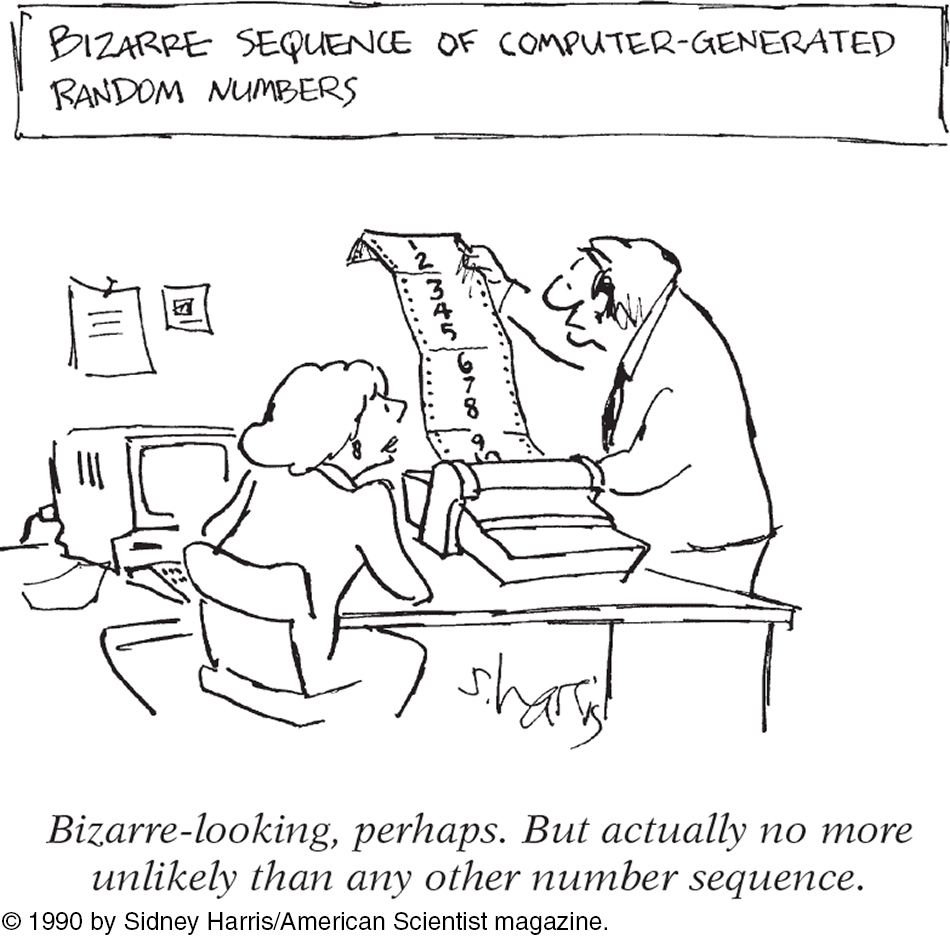

PERCEIVING ORDER IN RANDOM EVENTS We have a built-

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Consider how scientific inquiry can help you think smarter about hot streaks in sports with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If There Is a Hot Hand in Basketball?

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Consider how scientific inquiry can help you think smarter about hot streaks in sports with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If There Is a Hot Hand in Basketball?

17

Some happenings, such as winning the lottery twice, seem so extraordinary that we find it difficult to conceive an ordinary, chance-

The point to remember: Hindsight bias, overconfidence, and our tendency to perceive patterns in random events often lead us to overestimate our intuition. But scientific inquiry can help us sift reality from illusion.

The Scientific Method

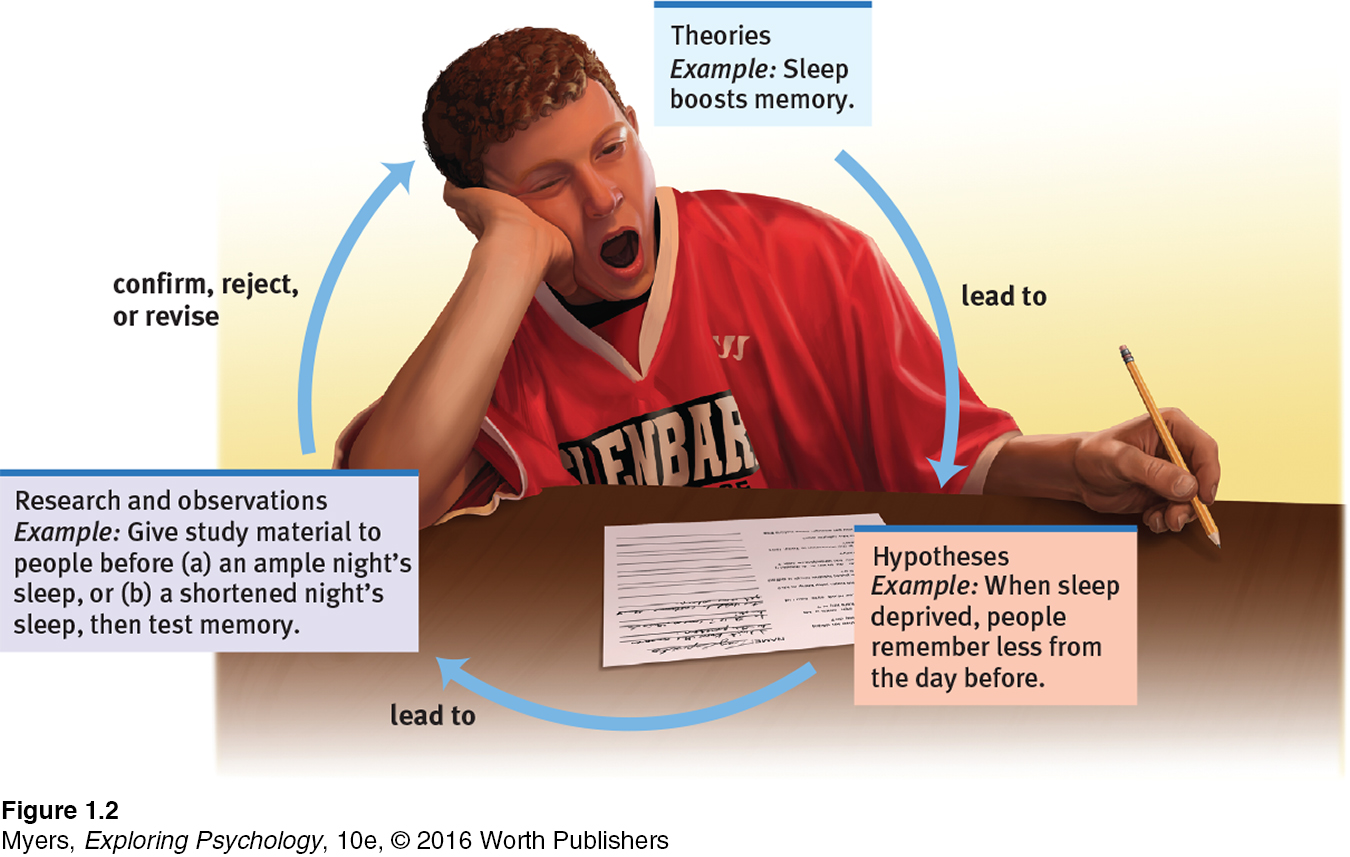

Psychologists arm their scientific attitude with the scientific method—

Constructing Theories

1-

theory an explanation using an integrated set of principles that organizes observations and predicts behaviors or events.

In everyday conversation, we often use theory to mean “mere hunch.” Someone might, for example, discount evolution as “only a theory”—as if it were mere speculation. In science, a theory explains behaviors or events by offering ideas that organize what we have observed. By organizing isolated facts, a theory simplifies. By linking facts with deeper principles, a theory offers a useful summary. As we connect the observed dots, a coherent picture emerges.

A theory about sleep effects on memory, for example, helps us organize countless sleep-

hypothesis a testable prediction, often implied by a theory.

Yet no matter how reasonable a theory may sound—

Our theories can bias our observations. Having theorized that better memory springs from more sleep, we may see what we expect: We may perceive sleepy people’s comments as less insightful. The urge to see what we expect is ever-

operational definition a carefully worded statement of the exact procedures (operations) used in a research study. For example, human intelligence may be operationally defined as what an intelligence test measures.

replication repeating the essence of a research study, usually with different participants in different situations, to see whether the basic finding can be reproduced.

As a check on their biases, psychologists report their research with precise operational definitions of procedures and concepts. Sleep deprived, for example, might be defined as “X hours less” than one’s natural sleep. Using these carefully worded statements, others can replicate (repeat) the original observations with different participants, materials, and circumstances. If they get similar results, confidence in the finding’s reliability grows. The first study of hindsight bias aroused psychologists’ curiosity. Now, after many successful replications with different people and questions, we feel sure of the phenomenon’s power. Although “mere replications” of others’ research are unglamorous—

18

In the end, our theory will be useful if it (1) organizes observations and (2) implies predictions that anyone can use to check the theory or to derive practical applications. (Does people’s sleep predict their retention?) Eventually, our research may (3) stimulate further research that leads to a revised theory that better organizes and predicts.

For more information about statistical methods that psychological scientists use in their work, see Appendix A, Statistical Reasoning in Everyday Life.

As we will see next, we can test our hypotheses and refine our theories using descriptive methods (which describe behaviors, often through case studies, naturalistic observations, or surveys), correlational methods (which associate different factors), and experimental methods (which manipulate factors to discover their effects). To think critically about popular psychology claims, we need to understand these methods and know what conclusions they allow.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

lsMn99gclYZcH+G5xtCOpNx5sEKhicOyof/ycyo1Irv6Ze2sXLQ43jnmug0TnIqTKks7V/7TINNGCuJkzFqFeAooahtDVHVxkTov7Q==Question

IM6VQHt/T8cOr0zyaU5U69CSvy5wU3tQNFmeBs5wBr+pKhq37oQ2EDOIIm/byZJmvuITDptoz6vnJPj+hUSw2NvkVRr96rGUK22TKQ==Description

1-

The starting point of any science is description. In everyday life, we all observe and describe people, often drawing conclusions about why they act as they do. Professional psychologists do much the same, though more objectively and systematically, through

case studies (in-

depth analyses of individuals or groups). naturalistic observations (recording individuals’ behavior in their natural setting).

surveys and interviews (self-

reports in which people answer questions about their behavior or attitudes).

“‘Well my dear,’ said Miss Marple, ‘human nature is very much the same everywhere, and of course, one has opportunities of observing it at closer quarters in a village’.”

Agatha Christie, The Tuesday Club Murders, 1933

case study a descriptive technique in which one individual or group is studied in depth in the hope of revealing universal principles.

19

THE CASE STUDY Among the oldest research methods, the case study examines one individual or group in depth in the hope of revealing things true of us all. Some examples: Much of our early knowledge about the brain came from case studies of individuals who suffered a particular impairment after damage to a certain brain region. Jean Piaget taught us about children’s thinking after carefully observing and questioning only a few children. Studies of only a few chimpanzees revealed their capacity for understanding and language. Intensive case studies are sometimes very revealing, and they often suggest directions for further study.

See LaunchPad's Video: Case Studies for a helpful tutorial animation.

See LaunchPad's Video: Case Studies for a helpful tutorial animation.

But atypical individual cases may mislead us. Both in our everyday lives and in science, unrepresentative information can lead to mistaken conclusions. Indeed, anytime a researcher mentions a finding (Smokers die younger: 95 percent of men over 85 are nonsmokers) someone is sure to offer a contradictory anecdote (Well, I have an uncle who smoked two packs a day and lived to be 89). Dramatic stories and personal experiences (even psychological case examples) command our attention and are easily remembered. Journalists understand that, and often begin their articles with personal stories. Stories move us. But stories can mislead. Which of the following do you find more memorable? (1) “In one study of 1300 dream reports concerning a kidnapped child, only 5 percent correctly envisioned the child as dead” (Murray & Wheeler, 1937). (2) “I know a man who dreamed his sister was in a car accident, and two days later she died in a head-

The point to remember: Individual cases can suggest fruitful ideas. What’s true of all of us can be glimpsed in any one of us. But to discern the general truths that cover individual cases, we must employ other research methods.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

oLh+ORRac3zNwWYs+O5gOIYA5UyDR8rJj7wD4nkokJvRMVyedJKwMVKOccpE+Zx6p0J02olfvg/pxlrVj7TmUU3qQ9PN+ssPsksdAddKmhbaH8nq+A/tVmPdk/GdVZ436L+f0csk4tQ+A849yHEfAHDFdEB0g2BAPtHecpX+rEa7ov4Mx19Sn6MaYs6MvAKdcXzuOg==naturalistic observation a descriptive technique of observing and recording behavior in naturally occurring situations without trying to manipulate and control the situation.

NATURALISTIC OBSERVATION A second descriptive method records behavior in natural environments. These naturalistic observations range from watching chimpanzee societies in the jungle, to videotaping and analyzing parent-

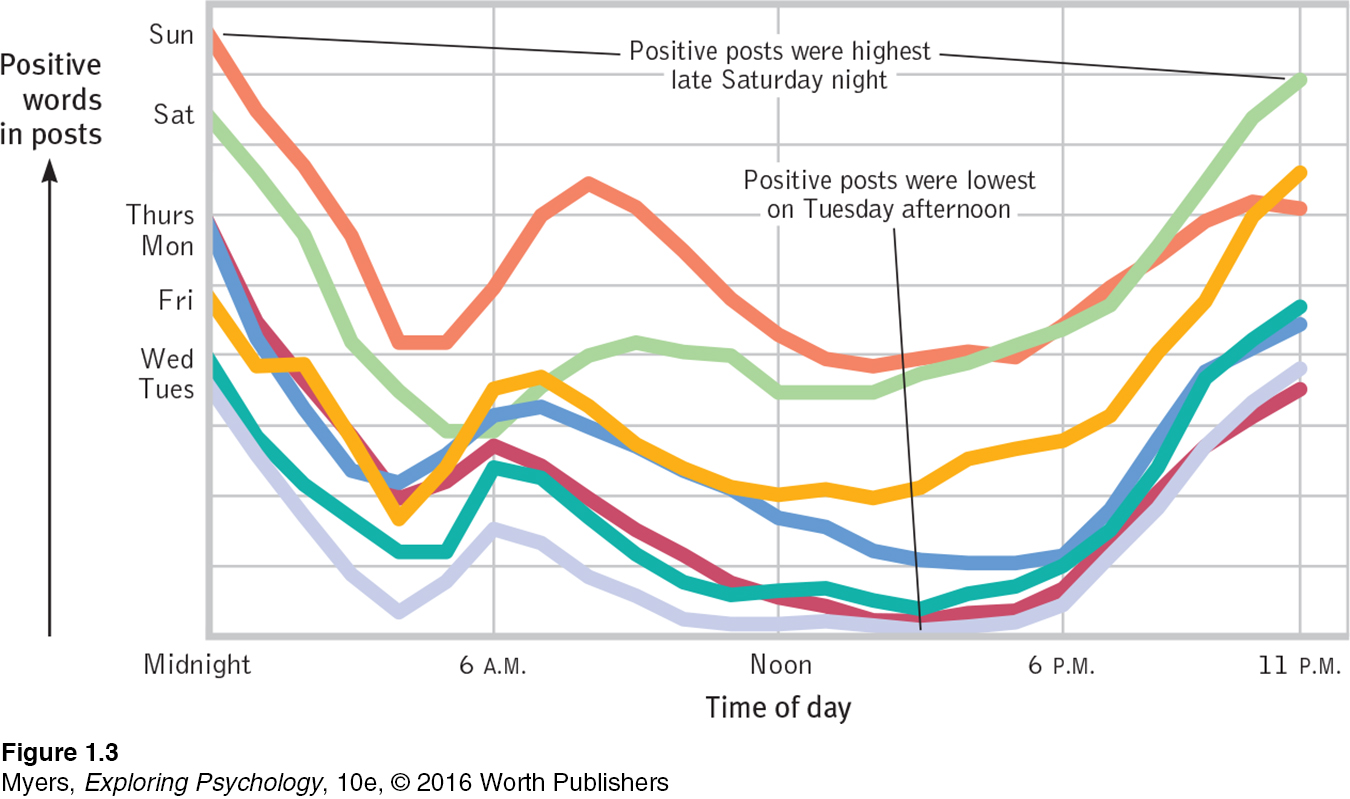

Naturalistic observation has mostly been “small science”—science that can be done with pen and paper rather than fancy equipment and a big budget (Provine, 2012). But new technologies, such as smart-

20

See LaunchPad's Video: Naturalistic Observation for a helpful tutorial animation.

See LaunchPad's Video: Naturalistic Observation for a helpful tutorial animation.

Like the case study, naturalistic observation does not explain behavior. It describes it. Nevertheless, descriptions can be revealing. We once thought, for example, that only humans use tools. Then naturalistic observation revealed that chimpanzees sometimes insert a stick in a termite mound and withdraw it, eating the stick’s load of termites. Such unobtrusive naturalistic observations paved the way for later studies of animal thinking, language, and emotion, which further expanded our understanding of our fellow animals. Thanks to researchers’ observations, we know that chimpanzees and baboons use deception: Psychologists repeatedly saw one young baboon pretending to have been attacked by another as a tactic to get its mother to drive the other baboon away from its food. “Observations, made in the natural habitat, helped to show that the societies and behavior of animals are far more complex than previously supposed,” chimpanzee observer Jane Goodall noted (1998).

Naturalistic observations also illuminate human behavior. Here are three findings you might enjoy:

A funny finding. We humans laugh 30 times more often in social situations than in solitary situations (Provine, 2001). (Have you noticed how seldom you laugh when alone?)

Sounding out students. What, really, are introductory psychology students saying and doing during their everyday lives? To find out, Matthias Mehl and James Pennebaker (2003) equipped 52 such students from the University of Texas with electronic recorders, which enabled the researchers to eavesdrop on more than 10,000 half-

minute life slices of students’ waking hours. On what percentage of the slices do you suppose they found the students talking with someone? The answer: 28 percent. Culture, climate, and the pace of life. Naturalistic observation also enabled Robert Levine and Ara Norenzayan (1999) to compare the pace of life—

the walking speed, speed of postal clerks, and so forth— in 31 countries. Their conclusion: Life is fastest paced in Japan and Western Europe and slower paced in economically less- developed countries.

Naturalistic observation offers interesting snapshots of everyday life, but it does so without controlling for all the factors that may influence behavior. It’s one thing to observe the pace of life in various places, but another to understand what makes some people walk faster than others. Even so, the observation of natural everyday behavior is an important part of psychological science.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

LPPmYBodPij58FtaWQH1TSNO40K/RcHILtD1n16xq2Jhh2qWvKdnkgeAzkawuOrYnii+pogmUjVc9z54pH4Ty+Ot1zG4fhmrXKoGwdH3K4EKPbCyNgZ4UxULuL0QZsSMH14KwOCezGLbYyUzVnRdoEB95tOkRWzOykVX/PvpMiRJLyQxjdoEctGgIQWE6us+Zkh0apuH0pCL844Cow9FJFg0/rk=survey a descriptive technique for obtaining the self-

21

THE SURVEY A survey looks at many cases in less depth by asking people to report their behavior or opinions. Questions about everything from sexual practices to political opinions are put to the public. In recent surveys:

Saturdays and Sundays have been the week’s happiest days (confirming what the Twitter researchers found) (Stone et al., 2012).

1 in 5 people across 22 countries report believing that alien beings have come to Earth and now walk among us disguised as humans (Ipsos, 2010b).

68 percent of all humans—

some 4.6 billion people— say that religion is important in their daily lives (from Gallup World Poll data analyzed by Diener et al., 2011).

But asking questions is tricky, and the answers often depend on question wording and respondent selection.

WORDING EFFECTS Even subtle changes in the order or wording of questions can have major effects. People are much more approving of “aid to the needy” than of “welfare,” of “affirmative action” than of “preferential treatment,” of “not allowing” televised cigarette ads and pornography than of “censoring” them, and of “revenue enhancers” than of “taxes.” Because wording is such a delicate matter, critical thinkers will reflect on how the phrasing of a question might affect people’s expressed opinions.

RANDOM SAMPLING In everyday thinking, we tend to generalize from cases we observe, especially vivid cases. Given (a) a statistical summary of a professor’s student evaluations and (b) the vivid comments of a biased sample (two irate students), an administrator’s impression of the professor may be influenced as much by the two unhappy students as by the many favorable evaluations in the statistical summary. The temptation to ignore the sampling bias and to generalize from a few vivid but unrepresentative cases is nearly irresistible.

population all those in a group being studied, from which samples may be drawn. (Note: Except for national studies, this does not refer to a country’s whole population.)

random sample a sample that fairly represents a population because each member has an equal chance of inclusion.

With very large samples, estimates become quite reliable. E is estimated to represent 12.7 percent of the letters in written English. E, in fact, is 12.3 percent of the 925,141 letters in Melville’s Moby-

So how do you obtain a representative sample of, say, the students at your college or university? It’s not always possible to survey the whole group you want to study and describe. How could you choose a group that would represent the total student population? Typically, you would seek a random sample, in which every person in the total group has an equal chance of being included in the sample group. You might number the names in the general student listing and then use a random number generator to pick your survey participants. (Sending each student a questionnaire wouldn’t work because the conscientious people who returned it would not be a random sample.) Large representative samples are better than small ones, but a small representative sample of 100 is better than an unrepresentative sample of 500.

Political pollsters sample voters in national election surveys just this way. Using some 1500 randomly sampled people, drawn from all areas of a country, they can provide a remarkably accurate snapshot of the nation’s opinions. Without random sampling (also called random selection), large samples—

The point to remember: Before accepting survey findings, think critically. Consider the sample. The best basis for generalizing is from a representative sample. You cannot compensate for an unrepresentative sample by simply adding more people.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

2OrLnGdIUsrdQ0gnzJCvYyJ1AOPiuXP7bK9Ey3dv904wtPZ60Xv4nmR20Lg4ajdJu6b9rBco0HvPDfRP2G7Xk+UPevTW+Jn6AUloVGeQJXAmiCOCx5kEc54vq0wxJd+fQgG1/WJ5spkxxHRm+aisIxmpWZU=Correlation

22

1-

correlation a measure of the extent to which two factors vary together, and thus of how well either factor predicts the other.

correlation coefficient a statistical index of the relationship between two things (from -1.00 to +1.00).

See LaunchPad's Video: Correlational Studies for a helpful tutorial animation.

See LaunchPad's Video: Correlational Studies for a helpful tutorial animation.

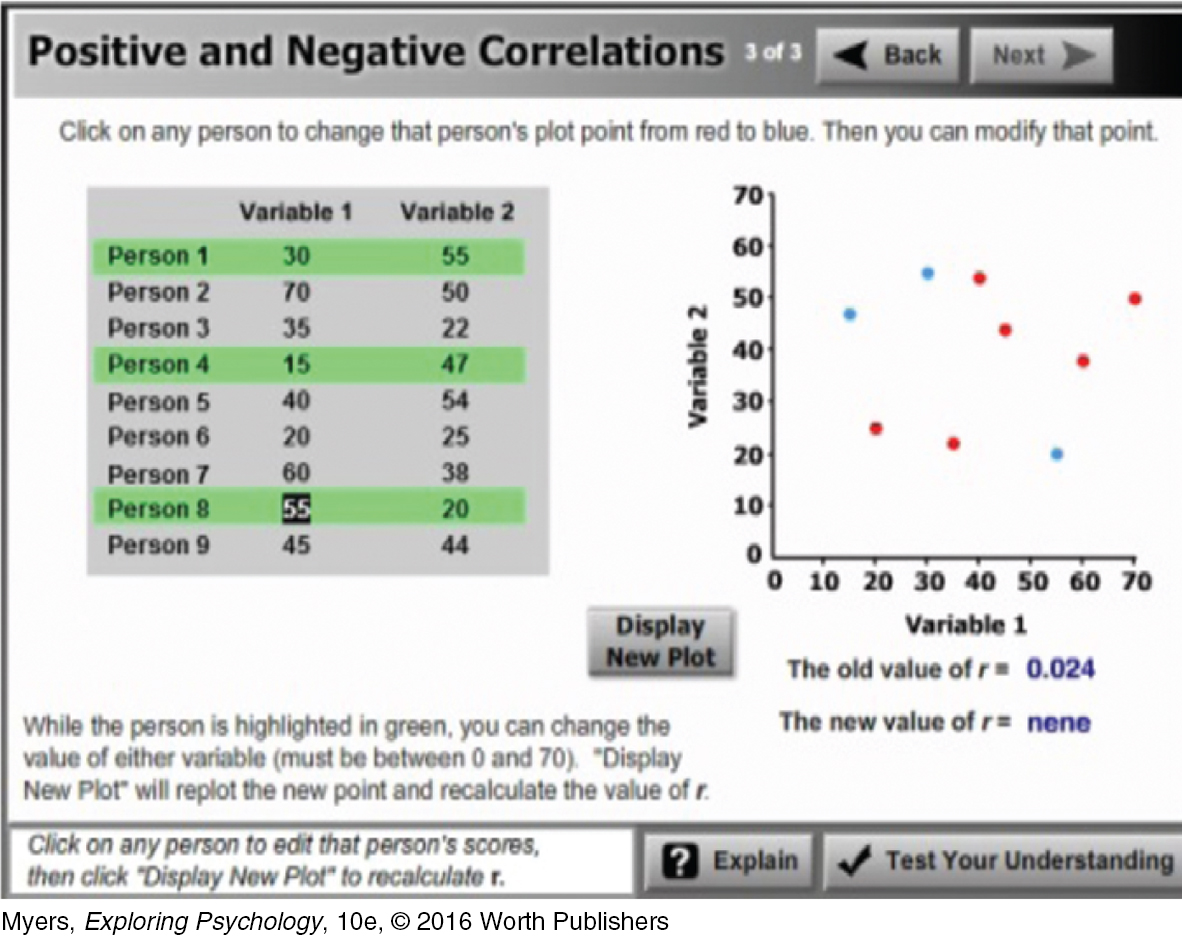

Describing behavior is a first step toward predicting it. Naturalistic observations and surveys often show us that one trait or behavior relates to another. In such cases, we say the two correlate. A statistical measure (the correlation coefficient) indicates how closely two things vary together, and thus how well either one predicts the other. Knowing how much aptitude test scores correlate with school success tells us how well the scores predict school success.

A positive correlation (above 0 to +1.00) indicates a direct relationship, meaning that two things increase together or decrease together. For example, height and weight are positively correlated.

A negative correlation (below 0 to −1.00) indicates an inverse relationship: As one thing increases, the other decreases. The weekly number of hours spent in TV watching and video gaming correlates negatively with grades. Negative correlations could go as low as −1.00, which means that, like people on opposite ends of a teeter-

Though informative, psychology’s correlations usually explain only part of the variation among individuals. As we will see, there is a positive correlation between parents’ abusiveness and their children’s later abusiveness when they become parents. But this does not mean that most abused children become abusive. The correlation simply indicates a statistical relationship: Most abused children do not grow into abusers, but nonabused children are even less likely to become abusive. Correlations point us toward predictions, but usually imperfect ones.

The point to remember: A correlation coefficient helps us see the world more clearly by revealing the extent to which two things relate.

RETRIEVE IT

Indicate whether each association is a positive correlation or a negative correlation.

Question

1. The more children and youth used various media, the less happy they were with their lives (Rideout et al., 2010).yU5mBK+8pkwzWnVv

Question

2. The less sexual content teens saw on TV, the less likely they were to have sex (Collins et al., 2004)./JNIEMPGMUF1stgb

Question

3. The longer children were breast-

Question

4. The more income rose among a sample of poor families, the fewer psychiatric symptoms their children experienced (Costello et al., 2003).yU5mBK+8pkwzWnVv

For an animated tutorial on correlations, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Positive and Negative Correlations.

For an animated tutorial on correlations, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Positive and Negative Correlations.

CORRELATION AND CAUSATION Consider some recent newsworthy correlations:

“Study finds that increased parental support for college results in lower grades” (Jaschik, 2013).

“People with mental illness more likely to be smokers, study finds” (Belluck, 2013).

“Teens who play mature-

rated, risk- glorifying video games [tend] to become reckless drivers” (Bowen, 2012).

What shall we make of these correlations? Do they indicate that students would achieve more if their parents supported them less? That stopping smoking would improve mental health? That abstaining from video games would make reckless teen drivers more responsible?

No, because such correlations do not come with built-

23

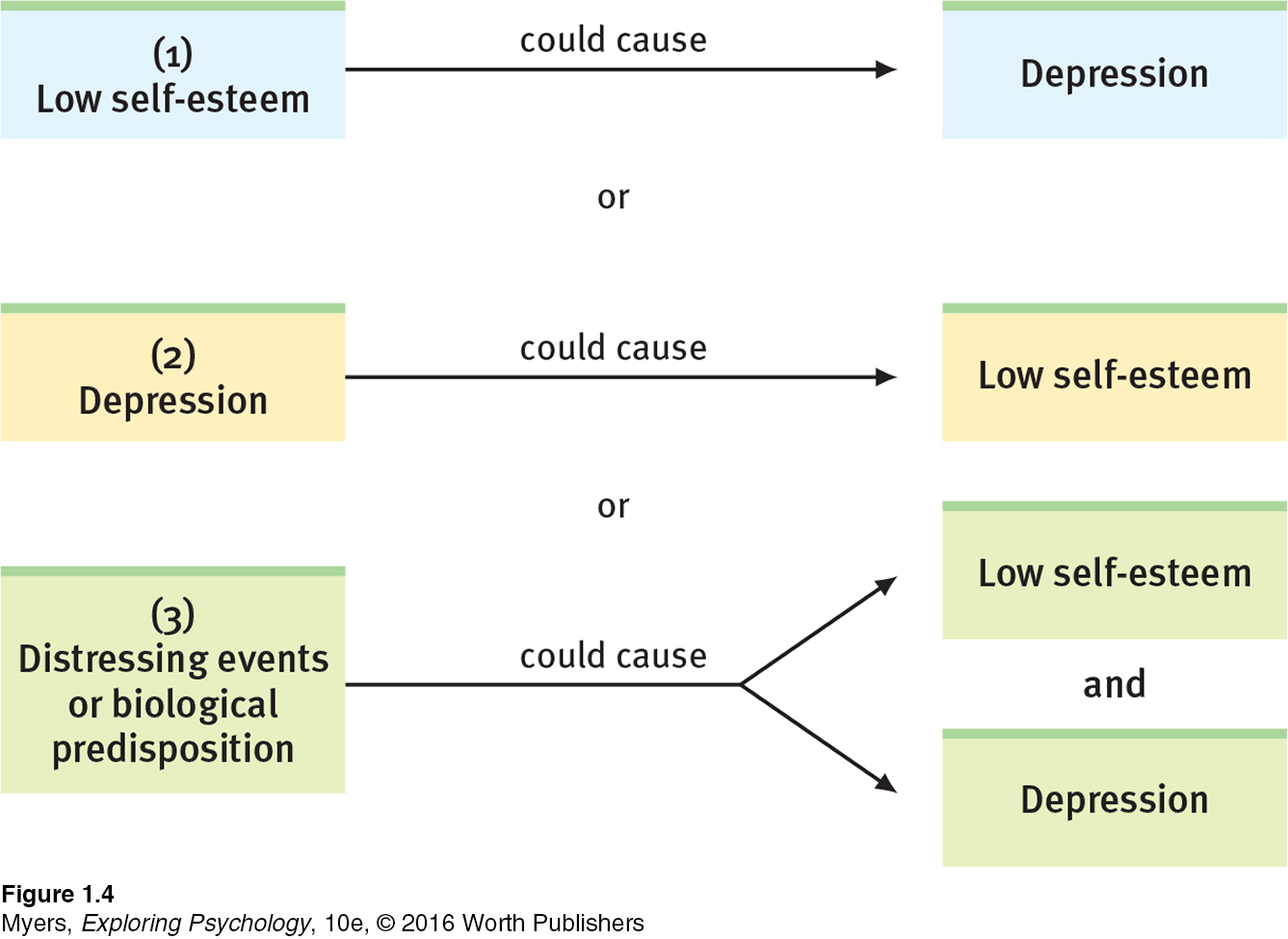

This point is so important—

The point to remember (turn the volume up here): Correlation does not prove causation. Correlation indicates the possibility of a cause-

RETRIEVE IT

Correlation need not mean causation.

Question

viIz7hlJxExNoJe9jWggNFOcDzjwC9t+PGG59Y6wn9AWxKnCRLEDZYkB4vFdshvipKPGEBo/G3DaAZjrqg5ZwQQUA6xzPnAZ9mn7bnTeBIRHCEFXx3EVIFUZI+zO8CfeRUWZSJd/FWHzeMjXV4ciF7dg5p+h+U5ng+6HBN2ZcEe6OypWepcvfkOKY6Esjq1dJkSJ+WWHsKu6Crpepxu1AdvubtEVA4bv2fTHJF79LT38POYIuxFgD4FkQ3UG4EYQ1DNtvuO9yeC/xQwRLDxBCbp/OsDxiKBAyHXbO6dCalvelC/jS6OPqPDZmc+QQHPEIpGKodOYwnBoQwu6T6S0WLqu8tplLM4IO8QISc7F56xGpUIkpka3a2pM6I0bByEvUF5ysXAf69x+trHn8LwDiNnTH2SS2389c/orOVWGKJtDq+r7bxHa/BkUErou/CZKBtlgu1DvcT2ZNHbUKh1LD1yS3AmkEssr1ehcoi9Nm1yHiWlbtPNa47H5dZZlLLg6trjpas0SsQR/+qTRsp/gyu7/OVF0k+IRWY79ow5IZNFJPPay/HrzfsqEFixwxBLQExperimentation

1-

Recall that in a well-

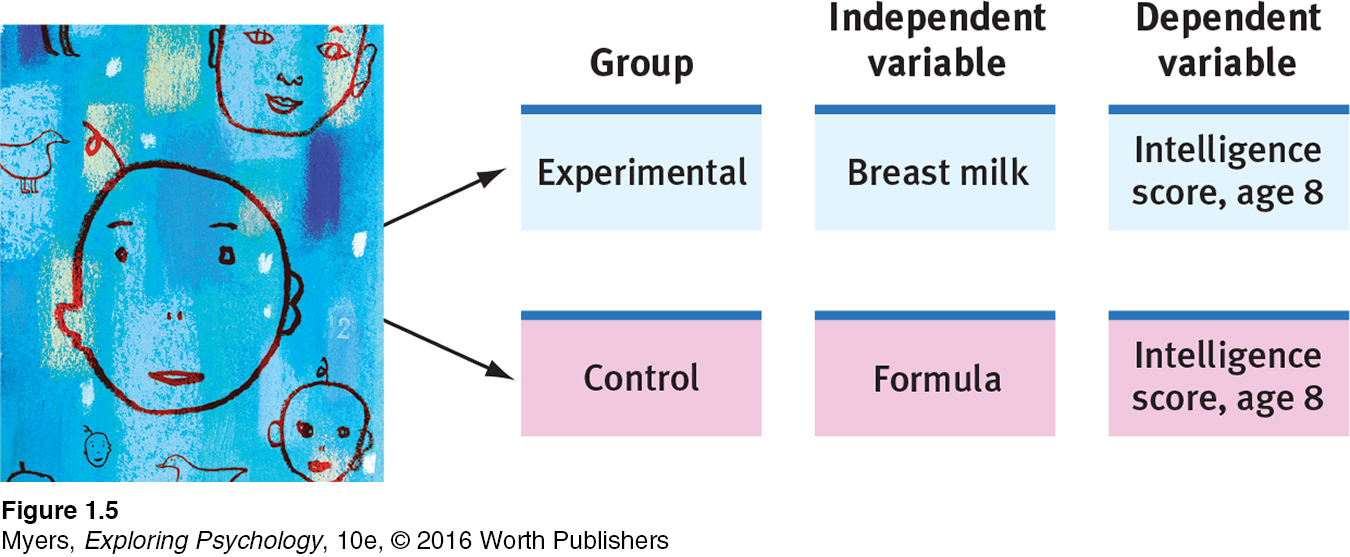

Happy are they, remarked the Roman poet Virgil, “who have been able to perceive the causes of things.” How might psychologists perceive causes in correlational studies, such as the correlation between breast feeding and intelligence? Is breast really best?

Intelligence scores of children who were breast-

experiment a research method in which an investigator manipulates one or more factors (independent variables) to observe the effect on some behavior or mental process (the dependent variable). By random assignment of participants, the experimenter aims to control other relevant factors.

experimental group in an experiment, the group exposed to the treatment, that is, to one version of the independent variable.

control group in an experiment, the group not exposed to the treatment; contrasts with the experimental group and serves as a comparison for evaluating the effect of the treatment.

random assignment assigning participants to experimental and control groups by chance, thus minimizing preexisting differences between the -different groups.

What do such findings mean? Do the nutrients of mother’s milk, as some researchers believe, contribute to brain development? Or do smarter mothers have smarter children? (Breast-

24

To experiment with breast feeding, one research team randomly assigned some 17,000 Belarus newborns and their mothers either to a control group given normal pediatric care, or to an experimental group that promoted breast feeding, thus increasing expectant mothers’ breast-

With parental permission, one British research team directly experimented with breast milk. They randomly assigned 424 hospitalized premature infants either to formula feedings or to breast-

See LaunchPad's Video: Random Assignment for a helpful tutorial animation.

See LaunchPad's Video: Random Assignment for a helpful tutorial animation.

No single experiment is conclusive, of course. But randomly assigning participants to one feeding group or the other effectively eliminated all factors except nutrition. This supported the conclusion that for developing intelligence, breast is indeed best. If test performance changes when we vary infant nutrition, then we infer that nutrition matters.

The point to remember: Unlike correlational studies, which uncover naturally occurring relationships, an experiment manipulates a factor to determine its effect.

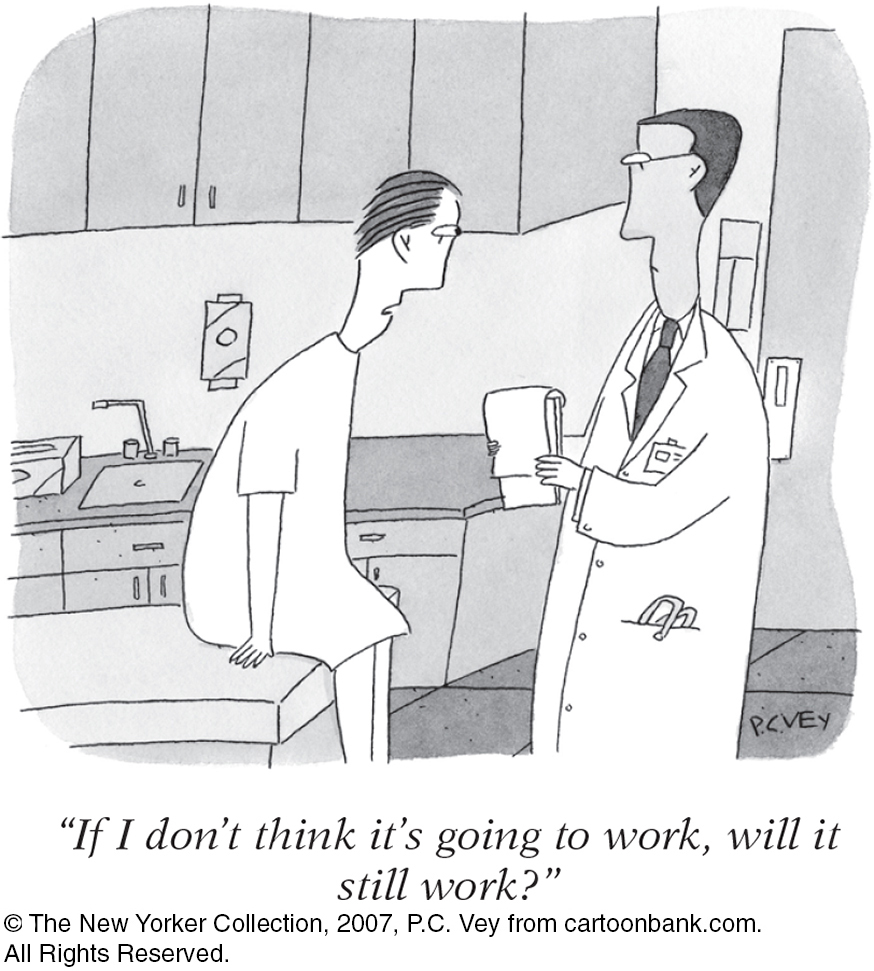

Consider, then, how we might assess therapeutic interventions. Our tendency to seek new remedies when we are ill or emotionally down can produce misleading testimonies. If three days into a cold we start taking vitamin C tablets and find our cold symptoms lessening, we may credit the pills rather than the cold naturally subsiding. In the 1700s, bloodletting seemed effective. People sometimes improved after the treatment; when they didn’t, the practitioner inferred the disease was too advanced to be reversed. So, whether or not a remedy is truly effective, enthusiastic users will probably endorse it. To determine its effect, we must control for other factors.

double-blind procedure an experimental procedure in which both the research participants and the research staff are ignorant (blind) about whether the research participants have received the treatment or a placebo. Commonly used in drug-

And that is precisely how investigators evaluate new drug treatments and new methods of psychological therapy (Chapter 15). They randomly assign participants either to the group receiving a treatment (such as a medication), or to a group receiving a pseudotreatment—

placebo [pluh-

In double-

25

RETRIEVE IT

Question

wBxEXiOX5MDTHMScaSdpBckO45bIoiO6Kp2cjC5qp8VmVymK6WlgA6h/84wBUncEHMiVH8K+y8oCSaUI/lLx41umBX5GXZOEspHlaX7pBRJCox15sxOqjr085iivmWlgN1HAeWW6iFkxlvD/HMHyc+aT4MIFPbfYZzJBluEsBd3cTayXRPXzgnFQuqlfmNsLgxkf2Q==

INDEPENDENT AND DEPENDENT VARIABLES Here is an even more potent example: The drug Viagra was approved for use after 21 clinical trials. One trial was an experiment in which researchers randomly assigned 329 men with erectile disorder to either an experimental group (Viagra takers) or a control group (placebo takers given an identical-

independent variable in an experiment, the factor that is manipulated; the variable whose effect is being studied.

confounding variable a factor other than the factor being studied that might produce an effect.

This simple experiment manipulated just one factor: the drug dosage (none versus peak dose). We call this experimental factor the independent variable because we can vary it independently of other factors, such as the men’s age, weight, and personality. Other factors which could influence a study’s results are called confounding variables. Random assignment controls for possible confounding variables.

dependent variable in an experiment, the outcome that is measured; the variable that may change when the independent variable is manipulated.

See two tutorial animations below: LaunchPad's Experiments and Confounding Variables.

See two tutorial animations below: LaunchPad's Experiments and Confounding Variables.

Experiments examine the effect of one or more independent variables on some measurable behavior, called the dependent variable because it can vary depending on what takes place during the experiment. Both variables are given precise operational definitions, which specify the procedures that manipulate the independent variable (in this study, the exact drug dosage and timing) or measure the dependent variable (the questions that assessed the men’s responses). These definitions answer the “What do you mean?” question with a level of precision that enables others to replicate the study. (See FIGURE 1.5 for the British breast milk experiment’s design.)

Let’s pause to check your understanding using a simple psychology experiment: To test the effect of perceived ethnicity on the availability of rental housing, Adrian Carpusor and William Loges (2006) sent identically worded e-

“[We must guard] against not just racial slurs, but … against the subtle impulse to call Johnny back for a job interview, but not Jamal.”

Barack Obama, Eulogy for Clementa Pinckney, June 26, 2015

Experiments can also help us evaluate social programs. Do early childhood education programs boost impoverished children’s chances for success? What are the effects of different antismoking campaigns? Do school sex-

Let’s recap. A variable is anything that can vary (infant nutrition, intelligence, TV exposure—

TABLE 1.2 compares the features of psychology’s main research methods. You will read later about other research designs, including cross-

26

Comparing Research Methods

| Research Method | Basic Purpose | How Conducted | What Is Manipulated | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive | To observe and record behavior | Do case studies, naturalistic observations, or surveys | Nothing | No control of variables; single cases may be misleading |

| Correlational | To detect naturally occurring relationships; to assess how well one variable predicts another | Collect data on two or more variables; no manipulation | Nothing | Cannot specify cause and effect |

| Experimental | To explore cause and effect | Manipulate one or more factors; use random assignment | The independent variable(s) | Sometimes not feasible; results may not generalize to other contexts; not ethical to manipulate certain variables |

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

Research Design: How Would You Know?

Throughout this book, you will read about amazing psychological science discoveries. But how do we know fact from fiction? How do psychological scientists choose research methods and design their studies in ways that provide meaningful results? Understanding how research is done—

In psychological research, no questions are off limits, except untestable ones. Does free will exist? Are people born evil? Is there an afterlife? Psychologists can’t test those questions, but they can test whether free will beliefs, aggressive personalities, and a belief in life after death influence how people think, feel, and act (Dechesne et al., 2003; Shariff et al., 2014; Webster et al., 2014).

To help you build your understanding, and your scientific literacy skills, we created IMMERSIVE LEARNING research activities in LaunchPad. In these How Would You Know activities, you get to play the role of the researcher, making choices about the best ways to test interesting questions, such as How Would You Know If Having Children Relates to Being Happier?, How Would You Know If a Cup of Coffee Can Warm Up Relationships?, and How Would You Know If People Can Learn to Reduce Anxiety?

Having chosen their question, psychologists then select the most appropriate research design—

Next, psychological scientists decide how to measure the behavior or mental process being studied. For example, consider the researchers mentioned earlier in this box, who tested whether aggressive personalities affect how people act. They measured aggression by determining participants’ willingness to blast a stranger with intense noise.

Researchers want to have confidence in their findings, so they carefully consider confounding variables—

Psychological research is a fun and creative adventure. The new Immersive Learning: How Would You Know? activities invite you to join the scientific journey to uncover new knowledge. We will both [DM and ND] encourage you via videos as you DESIGN each of your studies, MEASURE target behaviors, INTERPRET your results, and learn more about the fascinating process of scientific discovery along the way!

27

To review and test your understanding of experimental methods and concepts, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: The Language of Experiments, and the interactive PsychSim 6: Understanding Psychological Research. For a 9.5-

To review and test your understanding of experimental methods and concepts, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: The Language of Experiments, and the interactive PsychSim 6: Understanding Psychological Research. For a 9.5-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

NmKTQFV6Cp25eXaYR9koPthkWsqCsADyq7r4+4xBUctRSw6a6pstGuMEWBIGi8oTMlXZXX5GCH7fEYdoatvhR61bqgoO+hoD4t9xbuTGSIM2zV9DZu2bcYT3r34eahkDiZKwqkiIDkCYhvyzcTXvpu6VG3ll/WVj8/gPCsD/a159L0CK1sEVOUiPVhDlr4RQNqNrRrzG0mcEV84MH61yuqQEKbLyUZoOxKpQlJ8Gp3TmgC7SA6pQnXyH/4O1tg6asdoG3A==Question

By using random assignment, researchers are able to control for 0ZRuWpHgrpTl7/lAu3tnJuJ8b+HP15BCP1sxqg== , which are other factors besides the independent variable(s) that may influence research results.

Match the term on the left with the description on the right.

Question

wP+p60Nf4IGQLUc+TqidhoE8TUeKdiv8hfqzNGq9UWUBqD6nCucreN6V+rEcaADMyHwuPH9WnZVejkl5H5mmjKBaG9KJujEhPIwb9ARtAO09NQQUcXpUIZA/vUqDjojWeOfIB0aEIcF9wrP8+4tKVT6SqvXja0JGhQgX8YsjO9Yf39/Zk9gEbvo4NUbhyjvhADYxOLJfDRAvxp4/eWJROkSlLCeqe7WLDMsTULEXL/peNdEvJokHulu4aLETmh5WW75Nqv2CnAaXMlpzkTtM7b6tK8xqErcxIxLw57GvENkLAAlciFjzvyEeV0roFz30fNeFhDl6RPNKNz+zOQ3B9cCIAhqZ2ka9ZKNgAF7tWWNex6bP6hDchAj22IEU8FIA3stBVrsLR2epyu2sK8eL+E//5g/Ko/BVwmLXCk1iQ59hhDD/Z78VWMTRua5zbYo2NF+rAxQ7hc4=Question

/gSz8w1SI/J8nEBhLBe16t9IOCzAyoWf2vmfYOVQx0eme4L9ROKJZtBAYjuBrydjKOLTDKejtSt7GFm4ckqRwak93BrZryncRCtMjZB949JcC6E2HmDx6atJHz9lu96T5ZR2MuJE8f5mqCDyT+jqqcqAbYZ1rRvdpNFC0XLLXR3OjGZejQwyOc5mfGDm4LPtYSNay7RTHZx2I6tbNfFRkU7juDV9bRmN7qbOpdXTsQlR7GOttkxyk0udzPWX7XFlqheNAiPXWxjpKYYhfrR8dpO29rTxsY679WrChbp4Cr8yRa1+EnNs40Abqh5W7JLHPredicting Real Behavior

1-

When you see or hear about psychological research, do you ever wonder whether people’s behavior in the lab will predict their behavior in real life? Does detecting the blink of a faint red light in a dark room say anything useful about flying a plane at night? After viewing a violent, sexually explicit film, does an aroused man’s increased willingness to push buttons that he thinks will electrically shock a woman really say anything about whether violent pornography makes a man more likely to abuse a woman?

Before you answer, consider: The experimenter intends the laboratory environment to be a simplified reality—

An experiment’s purpose is not to re-

When psychologists apply laboratory research on aggression to actual violence, they are applying theoretical principles of aggressive behavior, principles refined through many experiments. Similarly, it is the principles of the visual system, developed from experiments in artificial settings (such as looking at red lights in the dark), that researchers apply to more complex behaviors such as night flying. And many investigations have demonstrated that principles derived in the laboratory do typically generalize to the everyday world (Anderson et al., 1999).

The point to remember: Psychological science focuses less on particular behaviors than on seeking general principles that help explain many behaviors.

Psychology’s Research Ethics

28

1-

See LaunchPad's Video: Research Ethics for a helpful tutorial animation.

See LaunchPad's Video: Research Ethics for a helpful tutorial animation.

We have reflected on how a scientific approach can restrain biases. We have seen how case studies, naturalistic observations, and surveys help us describe behavior. We have established how correlational studies assess the association between two factors, which indicates how well one thing predicts another. We have examined the logic that underlies experiments, which use control conditions and random assignment of participants to isolate the effects of an independent variable on a dependent variable.

Yet, even knowing this much, you may still be approaching psychology with a mixture of curiosity and apprehension. So before we plunge in, let’s entertain some common questions about psychology’s ethics and values.

Protecting Research Participants

STUDYING AND PROTECTING ANIMALS Many psychologists study nonhuman animals because they find them fascinating. They want to understand how different species learn, think, and behave. Psychologists also study animals to learn about people. We humans are not like animals; we are animals, sharing a common biology. Animal experiments have therefore led to treatments for human diseases—

“Rats are very similar to humans except that they are not stupid enough to purchase lottery tickets.”

Dave Barry, July 2, 2002

Humans are more complex, but the same processes by which we learn are present in rats, monkeys, and even sea slugs. The simplicity of the sea slug’s nervous system is precisely what makes it so revealing of the neural mechanisms of learning. Sharing such similarities, should we respect rather than experiment on our animal relatives? The animal protection movement protests the use of animals in psychological, biological, and medical research.

Out of this heated debate, two issues emerge. The basic one is whether it is right to place the well-

Second, if we do give human life first priority, what safeguards should protect the well-

Animals have themselves benefited from animal research. One Ohio team of research psychologists measured stress hormone levels in samples of millions of dogs brought each year to animal shelters. They devised handling and stroking methods to reduce stress and ease the dogs’ transition to adoptive homes (Tuber et al., 1999). Other studies have helped improve care and management in animals’ natural habitats. By revealing our behavioral kinship with animals and the remarkable intelligence of chimpanzees, gorillas, and other animals, experiments have also led to increased empathy and protection for them. At its best, a psychology concerned for humans and sensitive to animals serves the welfare of both.

“Please do not forget those of us who suffer from incurable diseases or disabilities who hope for a cure through research that requires the use of animals.”

Psychologist Dennis Feeney (1987)

“The greatness of a nation can be judged by the way its animals are treated.”

Mahatma Gandhi, 1869–

29

STUDYING AND PROTECTING HUMANS What about human participants? Does the image of white-

Occasionally, researchers do temporarily stress or deceive people, but only when they believe it is essential to a justifiable end, such as understanding and controlling violent behavior or studying mood swings. Some experiments won’t work if participants know everything beforehand. (Wanting to be helpful, the participants might try to confirm the researcher’s predictions.)

informed consent giving potential participants enough information about a study to enable them to choose whether they wish to participate.

debriefing the postexperimental explanation of a study, including its purpose and any deceptions, to its participants.

The ethics codes of the APA and the BPS urge researchers to (1) obtain human participants’ informed consent before the experiment, (2) protect participants from greater-

Values in Research

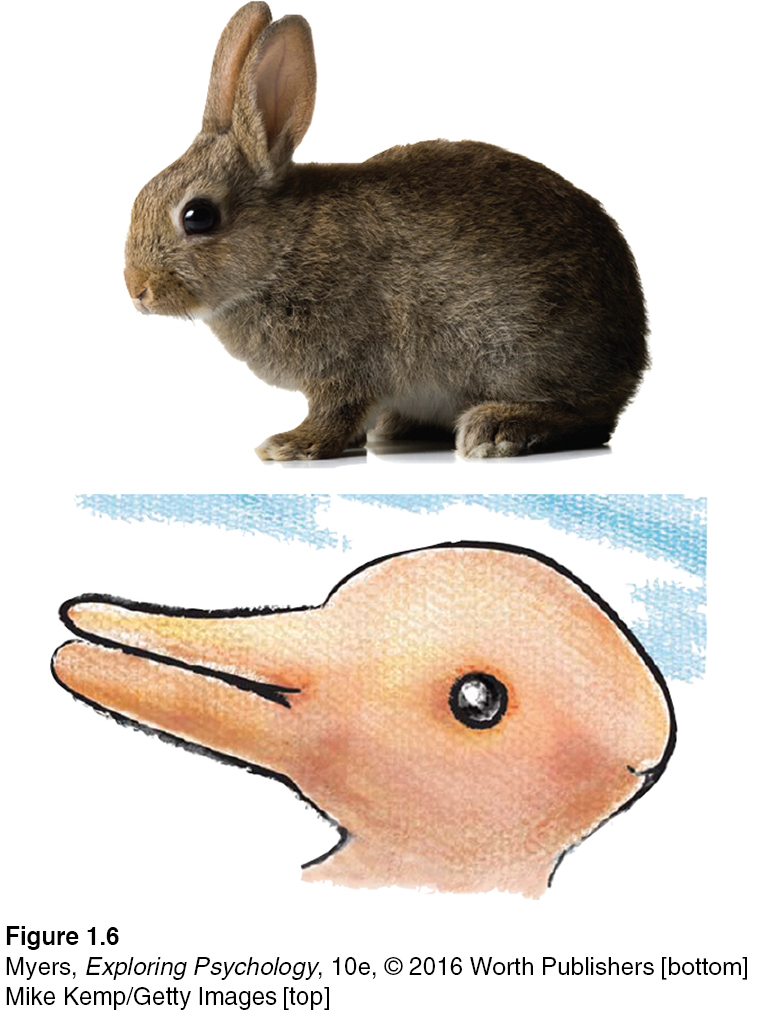

Values affect what we study, how we study it, and how we interpret results. Researchers’ values influence their choice of topics. Should we study worker productivity or worker morale? Sex discrimination or gender differences? Conformity or independence? Values can also color “the facts.” As we noted earlier, our preconceptions can bias our observations and interpretations; sometimes we see what we want or expect to see (FIGURE 1.6).

In psychology and in everyday speech, labels describe and labels evaluate: One person’s rigidity is another’s consistency. One person’s faith is another’s fanaticism. One country’s enhanced interrogation techniques become torture when practiced by its enemies. Our labeling someone as firm or stubborn, careful or picky, discreet or secretive reveals our own attitudes.

Popular applications of psychology also contain hidden values. If you defer to “professional” guidance about how to live—

Knowledge transforms us. Learning about the solar system and the germ theory of disease alters the way people think and act. Learning about psychology’s findings also changes people: They less often judge psychological disorders as moral failings, treatable by punishment and ostracism. They less often regard and treat women as men’s mental inferiors. They less often view and raise children as ignorant, willful beasts in need of taming. “In each case,” noted Morton Hunt (1990, p. 206), “knowledge has modified attitudes, and, through them, behavior.” Once aware of psychology’s well-

But bear in mind psychology’s limits. Don’t expect it to answer the ultimate questions, such as those posed by Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy (1904): “Why should I live? Why should I do anything? Is there in life any purpose which the inevitable death that awaits me does not undo and destroy?”

30

Although many of life’s significant questions are beyond psychology, some very important ones are illuminated by even a first psychology course. Through painstaking research, psychologists have gained insights into brain and mind, dreams and memories, depression and joy. Even the unanswered questions can renew our sense of mystery about “things too wonderful” for us yet to understand. Moreover, your study of psychology can help teach you how to ask and answer important questions—

If some people see psychology as merely common sense, others have a different concern—

Knowledge, like all power, can be used for good or evil. Nuclear power has been used to light up cities—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

mSCcqlRPh3mr4DY0fmQXb/pnAG3cpq+JYPmPd+uhCNucexwqrEUgratjVXsEoirOIeBgZLa3hpEs9K9LwCkLRi76YrkwSF/0o2G6lAmTavwPPhKgkN3kuPM4Tw19axQPvBjnvbjjjtE=Improve Your Retention—

1-

testing effect enhanced memory after retrieving, rather than simply rereading, information. Also referred to as a retrieval practice effect or test-

Do you, like most students, assume that the way to cement your new learning is to reread? What helps even more—

“If you read a piece of text through twenty times, you will not learn it by heart so easily as if you read it ten times while attempting to recite it from time to time and consulting the text when your memory fails.”

Francis Bacon, Novum Organum, 1620

As you will see in Chapter 8, to master information you must actively process it. Your mind is not like your stomach, something to be filled passively; it is more like a muscle that grows stronger with exercise. Countless experiments reveal that people learn and remember best when they put material in their own words, rehearse it, and then retrieve and review it again.

SQ3R a study method incorporating five steps: Survey, Question, Read, Retrieve, Review.

The SQ3R study method incorporates these principles (McDaniel et al., 2009; Robinson, 1970). SQ3R is an acronym for its five steps: Survey, Question, Read, Retrieve,4 Review.

31

To study a chapter, first survey, taking a bird’s-

Before you read each main section, try to answer its numbered Learning Objective Question (for this section: “How can psychological principles help you learn and remember?”). Roediger and Bridgid Finn (2009) have found that “trying and failing to retrieve the answer is actually helpful to learning.” Those who test their understanding before reading, and discover what they don’t yet know, will learn and remember better.

“It pays better to wait and recollect by an effort from within, than to look at the book again.”

William James, Principles of Psychology, 1890

Then read, actively searching for the answer to the question. At each sitting, read only as much of the chapter (usually a single main section) as you can absorb without tiring. Read actively and critically. Ask questions. Take notes. Make the ideas your own: How does what you’ve read relate to your own life? Does it support or challenge your assumptions? How convincing is the evidence?

Having read a section, retrieve its main ideas. “Active retrieval promotes meaningful learning,” says Karpicke (2012). So test yourself. This will help you figure out what you know. Moreover, the testing itself will help you learn and retain the information more effectively. Even better, test yourself repeatedly. To facilitate this, we offer periodic Retrieve It opportunities throughout each chapter (see, for example, the questions in this chapter). After trying to answer these questions yourself, you can check the answers, and reread as needed.

Finally, review: Read over any notes you have taken, again with an eye on the chapter’s organization, and quickly review the whole chapter. Write or say what a concept is before rereading to check your understanding.

Survey, question, read, retrieve, review. We have organized this book’s chapters to facilitate your use of the SQ3R study system. Each chapter begins with an outline that aids your survey. Headings and Learning Objective Questions suggest issues and concepts you should consider as you read. The material is organized into sections of readable length. The Retrieve It questions will challenge you to retrieve what you have learned, and thus better remember it. The end-

Four additional study tips may further boost your learning:

Distribute your study time. One of psychology’s oldest findings is that spaced practice promotes better retention than does massed practice. You’ll remember material better if you space your practice time over several study periods—

Spacing your study sessions requires a disciplined approach to managing your time. Richard O. Straub explains time management in a helpful preface at the beginning of this text.

Learn to think critically. Whether you are reading or in class, note people’s assumptions and values. What perspective or bias underlies an argument? Evaluate evidence. Is it anecdotal? Or is it based on informative experiments? Assess conclusions. Are there alternative explanations?

Process class information actively. Listen for a lecture’s main ideas and sub-

32

Overlearn. Psychology tells us that overlearning improves retention. We are prone to overestimating how much we know. You may understand a chapter as you read it, but that feeling of familiarity can be deceptively comforting. Using the Retrieve It opportunities, carve out study time for testing your knowledge.

Memory experts Elizabeth Bjork and Robert Bjork (2011, p. 63) offer the bottom line for how to improve your retention and your grades:

Spend less time on the input side and more time on the output side, such as summarizing what you have read from memory or getting together with friends and asking each other questions. Any activities that involve testing yourself—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

The ifr0PlSrMDFq+hBdeb+LNr6nhK0= describes the enhanced memory that results from repeated retrieval (as in self-testing) rather than from simple rereading of new information.

Question

93FmhV0lfs5j3rx5705qyVjC8+cDaoPP55UFClxyvYupEdAaHrRKx8NcCGxwYoMWjpV6j/CZ/cHigpbsoJeM2ZkNHcS8Y6REO6JkUr6R/55WOPyjLearning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

7jrJDqfWNIEYiPMifr/AkWHPQA/GtNNUnDRWZs9+IWjnCADALKLYSVIBF8WvK9CzI/PG4Y6SJ99NeEsNGiNIsJACcwIyruT0z4PuFVAuehwL04dltp3jxm0OMX+R9QJgooygKN0+hEkyn5CAhEAOezpdmNWsWgP/cr4LA/cW5KkXhFn86msG5ripNbafmFYdTIewA5nFSqbp60Ij3e9SJCDFTpcQcs51WKwFXc3/uQ+ZdlKsEUVXWDIKvvo=Question

3Sp6+MVnEeNRIfuTqvnBOdsAT3MWLAFdbI0axgVQFnJQ29iCnd1jV1Vhhi4gbKXy1kO2rukwG+WLollqWED2zVj+7Y7P4FdT1oNZ785hrtqAZn4Q7gmq8ml2+llmKbDsIC04mWgr8E2mjZ5zF7udZLgPwzFMAumK2UxlbE9fcsmQSPa/Mh+d8U58FX9o3hIkmwGYWYWxWcSWW0OC4vXp+Q==Question

TyHSuy9aoOMnDbW8eote68I52RZlLktlYTBfCO6lUEWNoX31+SY/VOXHW8/3+GKvYmkqaEDZ5x9U+Rsx439IJhFZrPxcZhQpT1+HTALA+Gcj8D+iLT5dBzq3f0xdjq8ZghgkF0zNMqFYikRxLyZhQVOL0miXX7aX+QQjgNfFfF1XmoR5zuzuLuAuSOO/2gB8IbzZqoadhnWn4qi8eiKIVJl2k8R4Gvbc1yKhS2mhV5c7liPyMi4cJ9in329ophnR8sdrXQesMBD6ythoE//KJ77sO0KxB9FXEHDQICHeEaSJ/n3EujPS74Gn0tlHMo12mPjzfVpJEBgIoVELMPY/+S0NMDY4N7ylQuestion

qA8UKOIVRB5IS7UlkIAYOz47ijNi/InPS43VXe8bwiOOM6pCSI/cM1oQrJxLTVWNPuIZaiF7E+BL89fswlyyhnAeaiAvB4Q3cTUx7X7tvYOMcjMAaHRJrNyJpNTgITZSH0RzxbVqOY1Lzijf9TxDpp9D3vTqxMPhvwqQJaZZ7fNMHsZKCZxarQ7sRCdFzl2C95nVfQ+2PvnmZla+guH76Cf3DFEiLTYNq8d+eM1+NcZaCQSuEOp488FJhsT/9XVLzDKSdkNJKTHHCHtLwmcA3bPkXo3vO6Cf6D2pw1RiEJqBo6ifqCWrGk2p0ZgOto0QIgVkRbXvhxgk5j25/6CBFUB0JBJUrq6xQk9rbnyP+SuM0C6LQuestion

iB3D49YP1WboiYapiZkI4Qw6X3tvpDgzPYLV/Awt2HzStF02siotUHOIPfglZDnt+a86pA8v8iN6K+WT/aVzRJ5kt+CdspvtaJptZFSzLI/scapISXNWLdA4kaFL/aY2Dkw0VXl7a3iL3V57MFnWkCUbjWxXzO6t7lS8s7CCgUSYrPq1D+S34rH/fJ+VZ1cqNx38bUlggev748ZgpD1Q4QzL8atQ0kKmgdUguO7L49p71AmDUdCW0r1to6L/Ldh3OvHnxXRnPJgnGBZVhx71FP7qAk4jULAPQuestion

RxM9doMzjZxZrvu0NqGp9hWtgeNjr1dJ/njrFyfOGwkNu4crlUXH22ZWYynmzxokEm889McJ4BkzTAgQ576vI/6YH9PBarp/w6fAQ11yBBQ0RYibhNBRAtEIJ83HwnTEV9JugqIf5ExvqeDuBRUPIhexnFlx7+QbdnQ4en1/az/OPKnx/4wOTxXNGeM/RsBiKcY38uCdeDAK4Z32DsYlQBLtS/q8TKFkQuestion

eUt3qlyWRkgveccJw9hT6eZpmSIDWOaDFx9HB883wVblmXmDoa7g2Rlvn07NBl2lnjmnefCSWAmZmvW7hcetPeZMVdBy4x0KUXMuLwFxcdO6PD4vGk9qWIwQsA/6K+CiTeCw5dErZxW2OJaNUspJOOLie1/rgNsa6YsecROZyny17OGfcyavog+1hV40ORosbui80+USlmm/RTEP0K+buMku4CZbcbucrpcpy0qvnhkKLRC/6NsdLsIekoSP0lTSfZ2OqJ3OinOjb3SMdQ/8IPCnS1cqbM/cpDugTUeccQuKA9Y+M1+VEnise5lac5ozZh10kISzm2yjH+QkOyYTQzc4ZrbgcQrVrdbjSZTCbZc=Question

gJpHGCdA5F/OeQmgBSYfPOFmXXzGyj4Br1vSiRd8gvmknSk+D9X1alALHP1Kp66djYGnxRT7ftq5g9TdTTLosZ0MDhxkiSRupcSPj7j/Yt/bUKy5bHgYSYeTqI86qoX5d/6fpNxmG6YJ3qyfaxqaQlhndwR4jb9A+DMnVHjrcitwHCxBtRDe78TlQuf5KWYEE8tSqjH2MokrQ7ZsQfazNPBN5VbZNdvvvc5aacvn4hQ=Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

iFiN2oCcdzPmZfAXhn78vz9QdF9xCAMuUxGFlHqa1EelZBxrwpXVUsM6CRJRksG4kkVegDAkWs0J6pgEyaab2eDoPzlpxtdrZq/jFHaaoTgK3UjocvoYmcKvykHeBx1l1fSnMILMEpfSWqKjq5QLkp/+2O+ahGQ40LRfBlORk11aXQWnSK+o+KFhat9tcsJ0gbx5e0XG6Vwj931K1m4zXT3TZsyBWqkw37GVYJ/uogLc84qtG9raywHcG37aN89fgYd6e5jP3IvNAvUIJGiHVWwko9kE2MU+V6KrwbfzoLr7k7da8/5dmeGOeulC082DWeo+KiHh6SEYw367XWBY1pjGXOkb7C/f6gZ7MRbD4ducQ6hGyFCXHjxnTmpldQ+2VdZD5NmYK+lQgknsdJMYt/y8USmjel+fZ2ObKB7Qj74labub72hlwKnw9C4lRUBwtQer1Tmjz8DMamw4XKZUh4jhtI7XYosMReyUvc9zodwip8ctXTDH80hnBu+EQakSPBlyUaKVNM8L7VAjrLNt6Zb9I46bw24j6cCSdblT/5Y7tiskHtTifX/ea1YwqnbEjbsTnuWLzPzfAiYz35tttGKdtGg9Fd8yRzNBmdj+JP+fziZm8IcVahNbeRLcq1GDqbke1pW5y1lCf+RbWEmY7IpkGRkx4f5XB66QnoAm5+BSuTsx+TXh4J86hPg1QazDXVodKgTf64Wv/5Mxk+dg3Vo/bQWFeUPvJzNkxAklahNtXQhhkS2PCGeAcpvugTSMsjto7TaXY5BsVXH9NFFZkf0FEfz/j8sIP7ujIJQmvcunMbZ7c/S57TwpGjc74nPTst9Ub87Rv53neK4F/3krMDbosmO9dHkVl04aWawAKVpoSc5WNKqqmF7nirNme/91cxjmn0cYVZPWxiq5sqTAnJTka6VYmsFhikJGlLU2D2knf/YKcoMLeLiNThmJnlcUd7emrcSskqXc+uAKDqfkpIL0u40ORYEYH0bEPXvdbcVpiO2QCeCvuD/JB7a6YjVWPHCG1TcBw4SeQG0IwIGbpHufhEjwuLY2ja70b06jeFB0k6IRMF1fUEB3QSLfXy2QDlHYi9BBAX1Mjy6oMEu3dufTXY45czIt9umUe+SoVZJHT0V3gKbI6Jt0bvodya3PoJF80Ic1/B70R2AOijEtt4It35RoyGEudt94OuAT2ZyEGoNp9Lo9NO9DYFd8qBrV2n46eEg80MEbXw+lX0YSAonybk4tSi8xfQpBFEYL+phQQH69n+Ha81MPKzPki2fhH0+WIRh3haHqAfyJuMm5ru3aMzyp/tgdk8lUB2vug3c8UOcsuMTVSyfzFx5GPrWE59J+Rd62MEnxgsGR8X0pjFixWsRK9Gjc3CjtTtEC70zH3z96ScXqnI8tLOKPwnzmlVHaoSuD6dCJ6PgnhES27foeGNXsfv87VAy1ucKuaDvyGRTMk7Uj39SBaypZ/78wPj+FgplMOq+LlsEMQvX34nVyzXx7E5KX0vMF/fjnjeLnvEAKGFny00qIGP3/H+1seQARlensb4IFJeEBcAkph6mFb7EsLoYAkkaboCSvWqdHNImUp825bAMdSRoMLChterhOp0/h4Cn10CN4mJfsRRuCtwqCTGGk1I/Ao8noOBG+mgARR/oHUyxMClWqKKt+W9sOzRYfAFKGLd8iMTi7M/UAXZ68G8C9hh2FCVo4BXW5KNrvnKkr/+YNQsBjlVnCgwWYDxyVZKexseqtYwAyBph35ggcF5Q0AuJLeU5IsBl8mcHKS2vQM9Z0HUwCqEyfbkg7LZsLxiLr9nfGU8QF9FH37GT3a34bq0eYJXJaeh0XZ0vCrR+6D9AmU4jbHZsw5wJvA4NBGj8PZ+LVDb7h4091Jm8wUvlCtECyxRT5Qh5tSWEpiH+K+8QjbWBdsZwRNuJ0aootkcfI8YQr4d0/9em5QGji5G4uF4wP7hzDlA9wdsdX5l9BYfuNol9qJGzEuoIYUxZnT/nI8C3vfRH0o30NaUt63nAxAoMtnhIXLAXFlFWccYXnsHuU8rmNT0HsI8zCSRWCPTP97I+yRY+g1TQSmBgU4scdfOP0ioWppXjxx/CTBzKvFNb141Ytn2Pfq6oAmYeqLicr2M6sbTZ2rGbkHTy3X526mE8QNCHOltwU8MQTnuNdZQ3bk66p47+ImXAtHB36S61mJzYwvt6yvh2ofL4MjYihllw/5G1j2J5A6OOQUoxOozIAGBcNwhnOMu2RnKLbC8wecLhbxnHasKspGC+0LuID5FmUep7GWbeJT6zqO+5bPuA4zx4cI68Atr4bFwp3HxsssgNXr/j3mPEcSGjyLnmda2kt456Uo7G4rj7Stjk/8HTnXoXE4Tqp5YnzThmELYVtomLz4dbNJnLgxhYxGg6caAnqfoHInLYq29GShj18Z/33pvO+DVAJC9/uNigiH1y/DQ8Lpy6K3O0FXzGJYhtO32UOxj7L88DgIL2G1YV0/wuKY5ZabtgdQx5rDUUZ7fjVW24x4TTQlmW3A7DjIsWe7EPgTHEjmSL8VVGkIipSwgXRhuey2xX2k2v4JSmrge2Wra1vU3+HPJjPLVWrQnFjIrrmOhyF0R2Bg4vYrWOU+bVAqUirSwJm5ZIzArtsNrquxbmhF2c7tnf19S5HFLbe8E9w5D7FgGjycdO3gYaWa8oS7vv9szL2pXR0mwAWDAJ1WuKmePrZQQm4DRHobi5k+JZiky1GD6AsWo34cAsd1hrkbE6jkq0gKuLPQhj7PsStNutzpRKVcUSyLMwSajRmg3QYVKGpWBfBv1vNse+kRtL9rVNzLDq3zt67kPUPmSD2/13xlQdZkoaX4VjvB5mYw06duu+/QgkCpIAAJw6RmKhiJO9DOKz2j4SRWal3+mSdu7dx2HsBgrepznzf5r08u78tD69eeh39XQvaX/TuPehCJZcD+Swq5BL+CxNkO5Nvge6ifJ3+pNmp7nqWW1iG8PWbluaYzw8PaC9zkE5/jfHz0tFVnY0ldNKuGvsGm2snl1TVBy4U3mtZz5BLNnQI8WHFm3NagUJkQ8wvTVX3hqa+c4ZzizFTL1UEezzu9PkfLi3sz4xtJ3VTiN5H8q8PNLaGevCLYVuHColh6FXJI+Y1j9ifzu4+ex/3Q4yxseQvJjqG9cGSCpJcLUhb0ZPu2F9caOzmKUmA1A3aE2SZGpDKPTNjTQ+3ty1HokAYqEtQ73AKU5jHjrtY8QQrMkx67RkDkvOhiIdK1OGoGMn+/esyPEnG1tmKxbgiA564sCGCYIy0Irgh+jbPXcJMAisVyltKK78ZaR8Lj7M8ekyXtjOs9ty/x4PQM4hmSYPBWRKSV2vebcExkYBv/FVURPi2tac8Qx4UbtLuaplQ9p4e45Byr91h4+h9KzQlL04oyMolNl4uDt50J4IA4ENsMRKYZ1hF2R7Q95XpHYTCToHNfywQx21LhSm54/Bu28hfyl7Np/RXyWMDAR5uW2xPPA4a2HWYVzLyqOQuesAnnOkowoblmCxtOkT35tDSTazNimlvvF5Qhj40pgV2mneqSBhCeysWRJZgDj62K/zu6HMbrZXYwehA8LxfPvrDxAw0QW/gcaDKLNP5uM02TDeCdmhkZOGNuIxcvuRvkuvDm/vMjAScCaQ/0923jCSBCYEjy1PAURDtQ9y2OAXyGw6FA4VnkHlBVDfa4g0qpeFYIWf52d/tP3j+q/ihln3Y28CgsEWJVK2Yxwo3atGe9+aqLQqveNbAMWZen7qVTLcXKMalQkAB6rVnZMCeGMz+IliecwBSzzi6cJUpAdzmzKi8TGbEgow9eIKUEU+bdDdKrCUKK6FeaMIjUDCe3eLaeZSXjyzjwG0vWsfy0tJ0kcamKZ/0VG4EobmmT57KnLVwyL2duYt5HoPAfjJKp4iOWH1DWTLoVbAbxtxEr0EU+FZjD1R9YeCX67WqUZrGewbP2n/A8qSI4FN384bz/qWawuTMpNyZgTasAQVGJfS44w522Kv7oLFl5xQ5k7ZLtz2yf36j38QVFmqRePgmy8CHgA1VCwfNQmyJbOcYKvvUwxR2sTNCESTY2ubz3GAaU4o4I4CWD5dTkiUZajlVwH8CY9XaVDLn3i6+SSoTD0jVYeWzVGKPtga8EOLufiKqrK7WHU0pTGudj3DMOcZvM/nQt9mfCRiZq9GGPAitv2S9EckhiVzSM6i4mhj2RB/X6RPBP0b/Bzlm7uceUWJ8xiRmTHPwmZVDz5oU6Jtzo1V5dVDOed432pCnLXCczuhymu93IWYeDRqTDUVSGdpB7kZYMj6V9PjWelmYzBzwrWLCqknd7VvoDHGIzuFL2PQMg08NNDGh5LB2UysNHLssSh0AVMcIxQaHDomcmNyERoWkg7AmCTzsoVCcdLY6s3OHFY3pJ0N1CQKz+BZb6YQ3ogsfAzwVS/CHpvofO06tnw5yT9WmmlQKzQDqbtrujzUBu6mLYiX0ZzLWHvO1KV6+Vnrx10wepSDAt6RZciu9f8dN7hvVDFg2psDdmlA+/j01GlzzgBdWUHjJ55fugi41Wrv/SxzozncV78MQou49GOWhXx9JPJRjqsKaWVOYcffJ2f7hYkbVPLbKMpwagUVlV1ynaZyP3PsGQcZ64FUdMK3rG1UMqBCtSwK8Fdga/Skbbcm5zup7lbi/d13INKk/UsytSeV7xli3Ta8ZTVGQ8FYtjLMhcr5NvXVkMfYqSnTp8EosPkmKDffnv8G48iXcbTbj1+3HBgsdgMWItE6RuFhdY9i8P8ksosvSdEatxT+cQkpXQyUUtOW8TNdAwAveCIhEKVWCFoxQLpqySYwO104XGLWWy5L+mu1G5qOdw8BeDUxtRmZKV2dBCO/ru/Y24l4eB2nmeVyKbZLp0rq8xMUDH9ZtLS/XZ2m/zd5QVZLrncHjuEPQKnVN+ugb67L1xZ7kbujO08ZEZXxrDhw8BSBObIQYdJPhjcy20pUx+eSLhVhG2MMYSUVshCaApzf36jtRAZjYu7ANVxnWdoXYOgo/71/ePtyRY4G7lIxzI/mZ6tXaqmPY+kPoEy58HRtFQAanE6wTFsnpsHyDiNhart7FZHUC3jyAJxaBryAqntDcM//t0IBFabhzMv81BPnJKMnKEPJWNnSPIrhddMOmpGZmy/FWDP52eHupUeZ9SC0MLP7gy0veouTkymd7UOZGN/PppN9zjwnsVlxthY+fobL+G+v8/z4LpVLwHELzEr87ldjI7BpvN2repWcQikLGLzbqQ91OnnPXfq6FHVtGxBHrquOAZUJLDQFotfIrsngS42WWY5R/hOO+y3gA7M0fsZanhPlZ/AVBOXLwRzlIMcujV1kPIOU6Eu3nZsIwniCl1negyZif7nRbsdCJ/KclGDCExVNAgbOkHJ9qwvgg4RkTDPeQJoINy5yKzmn+ALB1k5tUbjxeZRBHeevy47tktyyLY9WyBweuNLpU8EMxMTCg/qL8V4SSjHm6ZCI8IQoHSHmwb5p4x3pVeqIepZFOdd/zc0rkTjRv3j0VrxCzncArNKYYW895daFS7/2GqU3XNZFnMwFqIvXCohpJq8B2JverfnBwZQqwXZI91rv3wPGXjPDmg5MvwIYXjeSwkoK5xO6hr7Yg2DaVh4YVTFkt2KGnv9ATUgR2Lx6Zt1dshSor/uLafvnrKGACdudGRMO0pEjbctaM5qpDBKf7ZI1NBQnElqv7DySipla5AZqiPnMKuwQ0lm6UzJFVN9dCYSQ+a5R2Cnl8vveTQnJfxxzw1AZr9IchruTEyZCrFuIxFWB1n5XMtxdF62ybkqnkmkZxrPmwAbKykBs1KL9/sGwnkWkXh5L8JMqPgZQLT43xYRYaTHMYjcgO1EKw90K0Uzdrx7eAfplMVB6Yq8V4fwlx1sSdp5xU7UZvfL+33hZI2zvua2CnP9TYE6n7swXugCXn8j88tAs/PB/OpOe8qsmlM/DybGy5KpVTbQ4W0hzpA2mhCRHhXm8BzEquXkjPEiGLvEnM/PinOjmSKrTnprdVvTMEashtIVxb1fU3A1jyHcXkaVTRK8Yx+/zlDlweh/qFD1IYbtudm7rjRj/c5faavpYeJMU4/X0AhYT5qaPpkNta0LgHzEXT5y3hLjca5mQ6YPOsU6PDD2WM+5/FyeSSICzyirDeIHZgJYfkhtwSuvTRXWoH8g7dDBQn2RXe3ViqHJL5DUx7R9nPeK9RIfD8oeOLFVV4nXCZ3ygrBCAXGdZXZGRVeF5Ooi5XoRzEWI2/ncSIGEmRv4praCyXO4fn2/Ck1LZEpQx9Zmk251PSanCijW4pke+O1+IJzD2ENDCC2B7kJS5JuLSXzfSqz1wxwmsJpKfHrJ3Ip03wFkTxdF2XJFimnkBdVOYmkcrqawGIOwVZw85/aIzU2qCxjVNCudrPC72Lvc+0y4MmGI1jtQJ+qcSQy+g57uNlQx9WYFPeGQv2E4b7di2khZod76sn/7UxCCCCrml4Fz/Hf78ZWdbfv74=Experience the Testing Effect

33

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 1.9

1. TUOzdXeyQZS8frWa1DanU0SYFNI= refers to our tendency to perceive events as obvious or inevitable after the fact.

Question 1.10

4APFX2YNoFnuxbSnYoAgOgvWsZu9qITeqGsOsHFXupEAbBr8hX9ngAg1OrhniUu8MO47M2JjkzkniJVEIobEtX1Dfg7ocPOC1pGaJhHFeKlD3skx6O65bFIRZ+3ITIjawezPGtCk+nAbnvEPXDM9qZcLOHyAs35wsXeCk+7/O4MP0giixpJsHMTrpsda8zrSAHd66I7WXi9w4C+8BZkasGR3TQndbR5hvW8BgVBOFtd+VCyMPYlMUwF+NQ+x9zTMAeF0JvvPMYMqqO2IQLT3ADMmkjc9mbQq/HLXfgbssqybOCnxuljchvEGiUS57rl6xeNUparM8/cQe2xKurYLTIpK+AGJH5hsHvPzlm774cPIxbD8c3XlnL/Px126aHR0KCEI5Nrtki6gLv1k0wLHWG2RJxZizO/SIFS5EqpW66vu/0fvT6WWf4R4KED+JjTsYeR8uY5QzdCW4XY8LEgg1B+46tOh1nxc5GTDtzP2DOJIfN59plH7PpW0tijm8mraiCfSmyHzMDfoCxnEs9mFsZykKkk=Question 1.11

uXgoHabHCOjbaHh012Jq9/qbCxlwt2v6Ln02LfHvfrGNdLr6GPaFKesptNeRoOn/zS+FhZJu/YvD1wt/309bhFq+ooYISiy8Z3rDkfE7gpa1xJQXdK4a4dE0PixPnKpS3o20g7PGxibUIi3hzm9zMRe7G6p57hi4vtngJbLU6fr9iSSikSXKHRzQNcYoYyfg8huqDQz84bOfIsILGLKmv7mlrMgMJVTQ5D1qk1nyrVrDlPtHKHZQv5GCRswMDjYm4ubqRVNPdC0ZdzLtqbNBQ/GL6so=Question 1.12

4. Theory-based predictions are called Xt6eD+++j0GmFImFINyAVQ== .

Question 1.13

LLAlbNgIHt+CdmgACzx4DgchesAkOpc35aNsFgDcuo311cAUYrTdXb2VWI1qYlNw+6k1HXAbSqNN7WvYGS9rj/XURCwXRVb8ElDx0Ol7qK6GpGhlZqMSsmA5DsWv5ZnvUKVh9lVKrU4yMdT/jAvlhWy/Af/xHJ/jw6DT9c54ByL++co9P4k7n6o/d33sfpjgXGFp/a407IYV0uSQg7NQok/+oIgRM8gKoadj6MLbbkzA6SzcPoDpeddqPAuAacYrFoQh0mFIssTkvp2A46+RXBusfLxprmDeOVKSkKNp/lXkNgtrmD3cBIinPfawPGWEmJqnLkFmYdnqzI0BQuestion 1.14

6. You wish to survey a group of people who truly represent the country's adult population. The best way to ensure this is to question a 26WC62w0XIy27svEnxDbs4qKspg= sample of the population, in which each member has an equal chance of inclusion.

Question 1.15

7. A study finds that the more childbirth training classes women attend, the less pain medication they require during childbirth. This finding can be stated as a PsZo0R5Y8yrofAbHg+qqcQ== (positive/negative) correlation.

Question 1.16

dzEcxKNr69ucaeEgjMV3UDnr1/1NhATmfs8SAzss6yjy043V80MJVz3ltwZNVkW947lhFDCTyXCQuRoSgEm5RqglT+KEjQDBj14lpBkTbXsuJKTsQ7LPXiexMxTYSfhdc6xEOsywFKAX4DYfNysweuo7qDE4d3vEryqZLBLAmbnXGPwSupEOycYnBDixhSMJrR5gR93VaFaqQsZZLgDscSVN8PKJoQKK+okaUGeSv4c+Y2K9OEniFeCuIuKhlIqOckskXjEVK8ouDj76UwE7gt5loDVN4JTNgCmwYJX0cmVKMEWKCtbgdvEI6NYJd+voAHcHnkcYEGWrsr+Fbp7GtScdPFNf4Jst+B4uPPcTsJnGMCtpeoUVeyIisNIbqZ7HR1omuH5ADvE=Question 1.17

1IK3m7qbJiP7G2bgQ37hjPelJEVl5jk5ZQ6j4UE7mWj9+c3N69ht1DGAzwZTh8ot+dE84an1dXVIpxBFVyDDVrG9Wm9ppEx7kUcP+BzaRVD8a5JqckSYbETkqoenR+v2EFyCp06agCpClAPtqAIJXtvxVh1ULXnABSnAvd5Pp9Jc+Tg9xpq2LkN89E3/+rhGHYzGcVJQ9sfqfIjkgXtOUpSQHrKKSnVeAtJ+QKzSkL0miYqcFvGUIoO33wlZAvdGu9/lBT3CDL0Ex6C+JKTsT15o4b44CKeT5kd3jdsRmhAEjuW2/nq71Mutk8489lWso5B/dpxtx66l/LQPq90GwMCn7vhNgfJPXjLHjF+eWa0qUozsrnKTFza17gNwA+Pul9Nv4FgZ3UYvBToM0T8Mwr6ANx/bt7duOgHdnnyY2bI1DPHoUUgOCf2MUD1SLl3/tqwPQWhypUm+hp5k6oTWtFj7x8ivF6x85/ZHYohx+vue7dAbLpW9FBXoTa3pp8yOcHlTdblnYk45Amy4dd5NYahP+RfR/9rjbAqX2/978BSa5bdoSOF1mR/ZLkb0oxOUXr3QDvJ8b0LsNrk9U5RIE3k5ZyUmWr9+V839dfqFDsMTVUe5E8rEeD5N8cZsLGsabXZeZnZpTPJAtAqziD08UVwyJtcKgNtUOpJYRAnV9n/DprVXhugubW/Pi9cUcF0bm8rKn1l6Xj/JQ/YzPdJvQ6fraHXwCO/ohnobm18PjPjTJJ4KYC9d1aDfCgeyhjNB01IlfzoqEiFMdThTShKf/MN4+cIE2j9DlZ9gsw7JcuC7nBDVx1h/xKd1K3A3k2+veIDWYs0b0fk2hsJ0W5T+VPqZxMeoQ1LdtcTV6Za+dDvLNiRNIOPqT1OSLEIeDJe4gV1weRys54BVyoxiS2VCn1BtcenPTq2CVt1scGV7FbzgW00Arfv2vzHlI1I18vSTu48aEhkHqArbXlJPrZcSaaed++CGCyR+F6bWGWECtRj4Qtng+XGHEDYRxw5lFpR1SCvRM5l5fX90S/HHIEdc3rBf2RKs62MMu2Re0PvOjH/SlFt7droVPnMMHNmolRLc+gTHFwYNEgHV3OHqfyBOYVdokqwSsMtW2e3De4aXIKZYPg/oj3iaFVGH03Io205A/YPXpxThjK9YUQigqSbBOI9/9G0qyj5x37phV9MrjcMwxJVDOfHRePpVW2nyCNj/gyME510Cr7E+DAyT3nc/J7aSloB+D7Lxna+trOjB9yw=(b) Educated people live longer, on average, than less-educated people. (One interpretation: Education lengthens life and enhances health.) Perhaps richer people can afford more education and better health care. (Research supports this conclusion.)

(c) Teens engaged in team sports are less likely to use drugs, smoke, have sex, carry weapons, and eat junk food than are teens who do not engage in team sports. (One interpretation: Team sports encourage healthy living.) Perhaps some third factor explains this correlation — teens who use drugs, smoke, have sex, carry weapons, and eat junk food may be "loners" who do not enjoy playing on any team.

(d) Adolescents who frequently see smoking in movies are more likely to smoke. (One interpretation: Movie stars' behavior influences impressionable teens.) Perhaps adolescents who smoke and attend movies frequently have less parental supervision and more access to spending money than other adolescents.

Question 1.18

10. To explain behaviors and clarify cause and effect, psychologists use cQS+iRbatow7PC893D+Bhw== .

Question 1.19

11. To test the effect of a new drug on depression, we randomly assign people to control and experimental groups. Those in the control group take a pill that contains no medication. This is a 3AQn4csJ9riHGl+n .

Question 1.20

x3B7Gj4bCYaXr9nehfU1i9/wTGJfkTIY8G0OoDskpE8TfHvHCJ94nOptAs2u5vmAoZwbQQV4v0ExWlhlGAZ0rZ19VQsrknBlsgY5o0BixJoRvUreXmmH5Q3/d1KC6tUZPGH+V7rKE+D6BrfJeB4/jtG9RlCHQLeEPRkevuSo5oBDIMgHbyG6EtzNeojilXJkt1E8ngDUgCINp8R/kfcNvHNvWB82Q3YRe/YQYWuss4yCEZ2oiF5egpNfREchvHDYMq/9UsvlK+ONOWnUjqhQmrLnSRuR4GYywVTzq5eajyzr/RX+hV2L26JFUedMNPjL7kjq+ohEL7vS0gFH1EGVDVO8I3B1nN2ZcBV09CqmXydGKhnuRsh0IJoL7AYIvhxjPIvB7pb3l+TgRqtU7j5I1zl+kFBIgQd7Z91/U9iQdyFi2w6yeF8V/+aoiTKEZ4rrtcnVhBLpOiyJNetnKXZeP2EnpnCOtHLS5aP6t5MxI0e+HTNlJQ1dwUgIdvACzcz1+uQ6R8eP1YRJXphHJMotcpBLyxtaL0Zu+57+k68t1t6zDlxQCOqiTGySk1ujOGzimpMHjN9wsfE6rW0zxZhCAjOo4yd4juHRO/wsc8L5BF1lZ2SjaFGcaIWF6AIMHxvuKgmf8EpfyZ2xCjNyMYKHkihNYB6tcQt4soJ6Lw==Question 1.21

13. A researcher wants to determine whether noise level affects workers' blood pressure. In one group, she varies the level of noise in the environment and records participants' blood pressure. In this experiment, the level of noise is the OSUslen6MXCTFeOVyfwrHnS+HP7gIRGU4k3wIQ== .

Question 1.22

G1dvLMDSt8u7hFyE3Hkh7JDOu3rHBFC7dve5OFRN5mGPb6zg/PelIKx+UUGa6KUtiZ+uI6jptSuY/QtVpu9y6T1obHJ3JoPYav7Gw8suveR918UdWD/2zKjUcyHZc7HRIm0XUHpXRA7y6ImPOOpoue2xHNYHIHCHIAd0G2ykjo/t3eCdCxdaFzmPcCU6/LOb/HqXoTqoAVKtYhsYZKeVRVUkIFXkTRWGiIBE4TpoHKOPSROqepn33aP4URbus5k0GOkUYifIIJVYBYGSTyrAg5LaE3nq3iH7oKSMdo7rMDPPjARxGkx98RrqaRHtgerdzGlgqXxKUEF8to7F71ucMfbK8xKyXvqdc3ZvS9bY62g8XvDLV8skfQVcvI9a6siTFxm8ItIRaqZ3CbR8Question 1.23

Ond3t4wMJRUdEOv/oWBJ/Rvj3h6WNVy2thWv/CXk7DcYvI5oO+7vkPMag/NFioCPh576+qZp4cQr/UKyAYqRBW+OWOLrBH5nThLppJg/Qhy6i2mQbKYBjNtQWotaI8+HNrNQwSy6quO9PPM7e47oBBKuBv+ujRjU1GgM0ByZLUQxkMJaUD9MPMd+hv+DAsgOWrGPq8gU9UjIv/ZQ3JsjRpVU3S3mHiTOUGCpaeRO7rRodXymjxO9rtlR3w/U7IZZ3iRmZ9n8FQ0DkMIKrxq806g3wRnY7PcpmTpORbwR8et8bF2PKrgMDF5ZpDWB2uL+G+XWliNMFPhmsX16leTzBekC/Klz/jgd58XquWbZvs3toTGLCzfgsifFBMUPG6CfADcKmt1A2Qax07tYDdyckydjuFt9Xzu7CPQaJA0eYAzS40+MZB1E3p6Bsfil//KIgMWEjBf1TCXySdskMpwUt2pEjJsceWQOkFWm8wWOKSvqCNqmdUcQmFzxFWZJH7MdSPqomPDasUuH7n+Ox+9O9jJY5kRravMsaKznd/Mq3ny204jzUse  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.