Chapter 2 Introduction

34

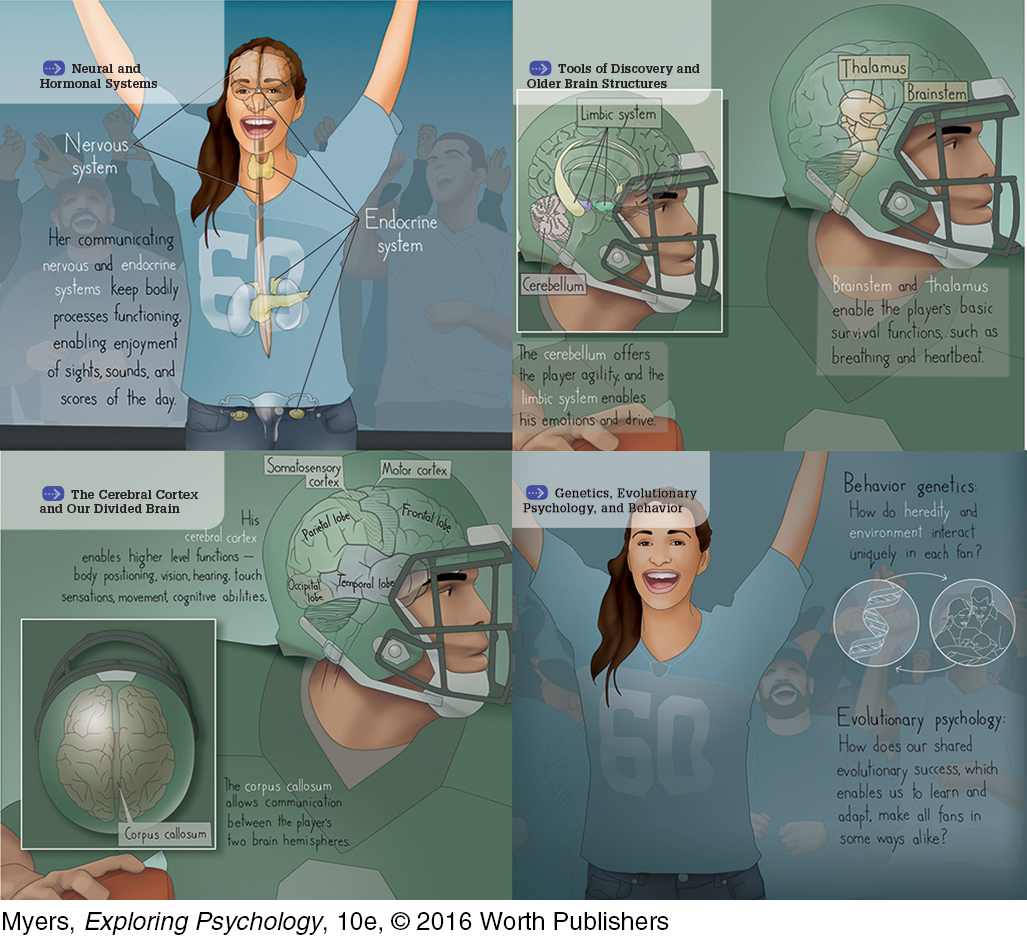

The Biology of Behavior

Neural and Hormonal Systems

Tools of Discovery and Older Brain Structures

The Cerebral Cortex and Our Divided Brain

Genetics, Evolutionary Psychology, and Behavior

35

IN 2000, a Virginia teacher began collecting sex magazines, visiting child pornography websites, and then making subtle advances on his young stepdaughter. When his wife called the police, he was arrested and later convicted of child molestation. Though put into a sexual addiction rehabilitation program, he still felt overwhelmed by his sexual urges. The day before being sentenced to prison, he went to his local emergency room complaining of a headache and thoughts of suicide. He was also distraught over his uncontrollable impulses, which led him to proposition nurses.

A brain scan located the problem—

This case illustrates what you likely believe: that you reside in your head. If surgeons transplanted all your organs below your neck, and even your skin and limbs, you would (Yes?) still be you. An acquaintance of mine [DM’s] received a new heart from a woman who, in a rare operation, had received a matched heart-

Indeed, no principle is more central to today’s psychology than this: Everything psychological is simultaneously biological. Throughout this book, you will find examples of this interplay.

In this chapter we start small and build from the bottom up—