5.2 Human Sexuality

181

asexual having no sexual attraction to others.

As you’ve probably noticed, we can hardly talk about gender without talking about our sexuality. For all but the tiny fraction of us considered asexual, dating and mating become a high priority from puberty on. Our emerging sexual feelings and behaviors reflect both physiological and psychological influences.

The Physiology of Sex

Sex is not like hunger, because it is not an actual need. (Without it, we may feel like dying, but we will not.) Yet sex is a part of life. Had this not been so for all your ancestors, you would not be reading this book. Sexual motivation is nature’s clever way of making people procreate, thus enabling our species’ survival. When we feel an attraction, we hardly stop to think of ourselves as guided by ancestral genes. We may crave our partner’s presence, with a brain response similar to when someone struggles with an alcohol craving (Acevedo et al., 2012). As the pleasure we take in eating is nature’s method of getting our body nourishment, so the desires and pleasures of sex are our genes’ way of preserving and spreading themselves. Life is sexually transmitted.

“It is a near-

Science writer Natalie Angier, 2007

Hormones and Sexual Behavior

5-

estrogens sex hormones, such as estradiol, secreted in greater amounts by females than by males and contributing to female sex characteristics. In nonhuman female mammals, estrogen levels peak during ovulation, promoting sexual receptivity.

Among the forces driving sexual behavior are the sex hormones. The main male sex hormone, as we saw earlier, is testosterone. The main female sex hormones are the estrogens, such as estradiol. Sex hormones influence us at many points in the life span:

During the prenatal period, they direct our development as males or females.

During puberty, a sex hormone surge ushers us into adolescence.

After puberty and well into the late adult years, sex hormones activate sexual behavior.

In most mammals, nature neatly synchronizes sex with fertility. Females become sexually receptive (in nonhumans, “in heat”) when their estrogens peak at ovulation. In experiments, researchers can cause female animals to become receptive by injecting them with estrogens. Male hormone levels are more constant, and hormone injection does not so readily affect the sexual behavior of male animals (Feder, 1984). Nevertheless, male rats that have had their testosterone-

Hormones do influence human sexual behavior, but in a looser way. Researchers are exploring and debating whether women’s mate preferences change across the menstrual cycle (Gildersleeve et al., 2014; Wood et al., 2014). Some evidence suggests that, among women with mates, sexual desire rises slightly at ovulation, when there is a surge of estrogens and a smaller surge of testosterone—

Women have much less testosterone than men do. And more than other mammalian females, women are responsive to their testosterone level (van Anders, 2012). If a woman’s natural testosterone level drops, as happens with removal of the ovaries or adrenal glands, her sexual interest may wane. But as experiments with hundreds of surgically or naturally menopausal women have demonstrated, testosterone-

In human males with abnormally low testosterone levels, testosterone-

182

Large hormonal surges or declines affect men and women’s desire in shifts that tend to occur at two predictable points in the life span, and sometimes at an unpredictable third point:

The pubertal surge in sex hormones triggers the development of sex characteristics and sexual interest. If the hormonal surge is precluded—

as it was during the 1600s and 1700s for prepubertal boys who were castrated to preserve their soprano voices for Italian opera— sex characteristics and sexual desire do not develop normally (Peschel & Peschel, 1987). In later life, hormone levels fall. Women experience menopause, males a more gradual change (Chapter 4). As sex hormone levels decline, sex remains a part of life, but the frequency of sexual fantasies and intercourse subsides (Leitenberg & Henning, 1995).

For some, surgery or drugs may cause hormonal shifts. When adult men were castrated, sex drive typically fell as testosterone levels declined sharply (Hucker & Bain, 1990). Male sex offenders who take Depo-

Provera, a drug that reduces testosterone levels to that of a prepubertal boy, have similarly lost much of their sexual urge (Bilefsky, 2009; Money et al., 1983).

To summarize: We might compare human sex hormones, especially testosterone, to the fuel in a car. Without fuel, a car will not run. But if the fuel level is minimally adequate, adding more fuel to the gas tank won’t change how the car runs. The analogy is imperfect, because hormones and sexual motivation interact. However, it correctly suggests that biology is a necessary but not sufficient explanation of human sexual behavior. The hormonal fuel is essential, but so are the psychological stimuli that turn on the engine, keep it running, and shift it into high gear.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

The primary male sex hormone is wzAcpRam18j43JRR4nv+IabbYWI= . The primary female sex hormones are the k111tWXfcTWrHjP7WeIWJQ== .

The Sexual Response Cycle

5-6 What is the human sexual response cycle, and how do sexual dysfunctions and paraphilias differ?

sexual response cycle the four stages of sexual responding described by Masters and Johnson—

The scientific process often begins with careful observations of complex behaviors. When gynecologist-obstetrician William Masters and his collaborator Virginia Johnson (1966) applied this process to human sexual intercourse in the 1960s, they made headlines. They recorded the physiological responses of volunteers who came to their lab to masturbate or have intercourse. With the help of 382 female and 312 male volunteers—

refractory period a resting period after orgasm, during which a man cannot achieve another orgasm.

Excitement The genital areas become engorged with blood, causing a woman’s clitoris and a man’s penis to swell. A woman’s vagina expands and secretes lubricant; her breasts and nipples may enlarge.

183

Plateau Excitement peaks as breathing, pulse, and blood pressure rates continue to increase. A man’s penis becomes fully engorged—

to an average length of 5.6 inches among 1661 men who measured themselves for condom fitting (Herbenick et al., 2014). Some fluid— frequently containing enough live sperm to enable conception— may appear at its tip. A woman’s vaginal secretion continues to increase, and her clitoris retracts. Orgasm feels imminent. Orgasm Muscle contractions appear all over the body and are accompanied by further increases in breathing, pulse, and blood pressure rates. A woman’s arousal and orgasm facilitate conception: They help draw semen from the penis, position the uterus to receive sperm, and carry the sperm further inward, increasing retention (Furlow & Thornhill, 1996). The pleasurable feeling of sexual release is much the same for both sexes. One panel of experts could not reliably distinguish between descriptions of orgasm written by men and those written by women (Vance & Wagner, 1976). In another study, PET scans showed that the same subcortical brain regions were active in men and women during orgasm (Holstege et al., 2003a,b).

Resolution The body gradually returns to its unaroused state as the genital blood vessels release their accumulated blood. This happens relatively quickly if orgasm has occurred, relatively slowly otherwise. (It’s like the nasal tickle that goes away rapidly if you have sneezed, slowly otherwise.) Men then enter a refractory period that lasts from a few minutes to a day or more, during which they are incapable of another orgasm. A woman’s much shorter refractory period may enable her, if restimulated during or soon after resolution, to have more orgasms.

A nonsmoking 50-year-

Sexual Dysfunctions and Paraphilias

sexual dysfunction a problem that consistently impairs sexual arousal or functioning.

erectile disorder inability to develop or maintain an erection due to insufficient bloodflow to the penis.

female orgasmic disorder distress due to infrequently or never experiencing orgasm.

Masters and Johnson sought not only to describe the human sexual response cycle but also to understand and treat the inability to complete it. Sexual dysfunctions are problems that consistently impair sexual arousal or functioning. Some involve sexual motivation, especially lack of sexual energy and arousability. For men, others include erectile disorder (inability to have or maintain an erection) and premature ejaculation. For women, the problem may be pain or female orgasmic disorder (distress over infrequently or never experiencing orgasm). In separate surveys of some 3000 Boston women and 32,000 other American women, about 4 in 10 reported a sexual problem, such as orgasmic disorder or low desire, but only about 1 in 8 reported that this caused personal distress (Lutfey et al., 2009; Shifren et al., 2008). Most women who have experienced sexual distress have related it to their emotional relationship with their partner during sex (Bancroft et al., 2003).

Therapy can help men and women with sexual dysfunctions (Frühauf et al., 2013). In behaviorally oriented therapy, for example, men learn ways to control their urge to ejaculate, and women are trained to bring themselves to orgasm. Starting with the introduction of Viagra in 1998, erectile disorder has been routinely treated by taking a pill. Some more modestly effective drug treatments for female sexual interest/arousal disorder are also available.

paraphilias sexual arousal from fantasies, behaviors, or urges involving nonhuman objects, the suffering of self or others, and/or nonconsenting persons.

Sexual dysfunction involves problems with arousal or sexual functioning. People with paraphilias do experience sexual desire, but they direct it in unusual ways. The American Psychiatric Association (2013) only classifies such behavior as disordered if

a person experiences distress from an unusual sexual interest or

it entails harm or risk of harm to others.

The serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer had necrophilia, a sexual attraction to corpses. Those with exhibitionism derive pleasure from exposing themselves sexually to others, without consent. People with the paraphilic disorder pedophilia experience sexual arousal toward children who haven’t entered puberty.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

184

5-

Every day, more than 1 million people worldwide acquire a sexually transmitted infection (STI; also called STD for sexually transmitted disease) (WHO, 2013). Teenage girls, because of their not yet fully mature biological development and lower levels of protective antibodies, are especially vulnerable (Dehne & Riedner, 2005; Guttmacher, 1994). A Centers for Disease Control study of sexually experienced 14-

To comprehend the mathematics of infection transmission, imagine this scenario. Over the course of a year, Pat has sex with 9 people, each of whom, by that point in time, has had sex with the same number of partners as has Pat. How many partners—

Condoms offer only limited protection against certain skin-

AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) a life-

Across the available studies, condoms also have been 80 percent effective in preventing transmission of HIV (human immunodeficiency virus—the virus that causes AIDS) from an infected partner (Weller & Davis-

Most Americans with AIDS have been in midlife and younger—

Many people assume that oral sex falls in the category of “safe sex,” but recent studies show a significant link between oral sex and transmission of STIs, such as the human papillomavirus (HPV). Risks rise with the number of sexual partners (Gillison et al., 2012). Most HPV infections can now be prevented with a vaccination administered before sexual contact.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

The inability to complete the sexual response cycle may be considered a AGKT87aey3V8xgYrkP6TFbi9WbDCwMbK . Exhibitionism would be considered a EYzlRgLzeKhAAKc8HWOfxQ== .

Question

AcTvkh1+C4911iepIyqqQyfvg+5OfgUpJuWtRExKOHtJvKmV4SASQulkaNsUmRifSxcHz1kLe8z8PISNikzn27PcRNYoGozPIWJa9BtRzXI2cVgs0uuDizNo4iA1SOZ3kW14Taoz48CJYJK5grhuFHp2mH+t+xEOtrtb4d9ILkaZuCV3xcV7Y9b6jybNznUaYRdTEH+PIP0PBONN9Pzn+o+Jdy0=The Psychology of Sex

185

5-

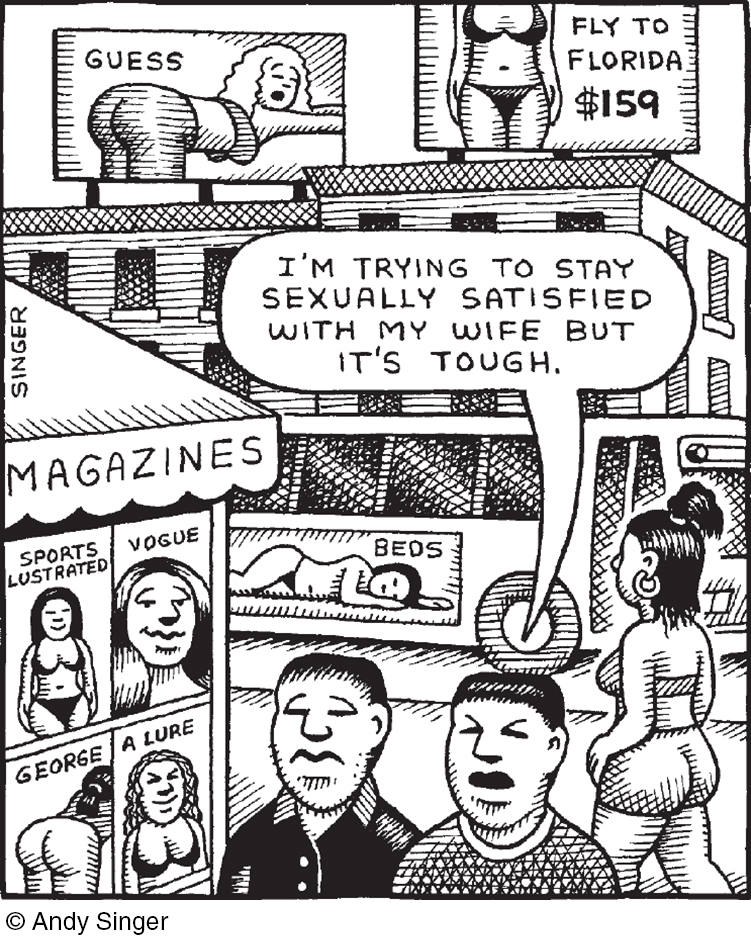

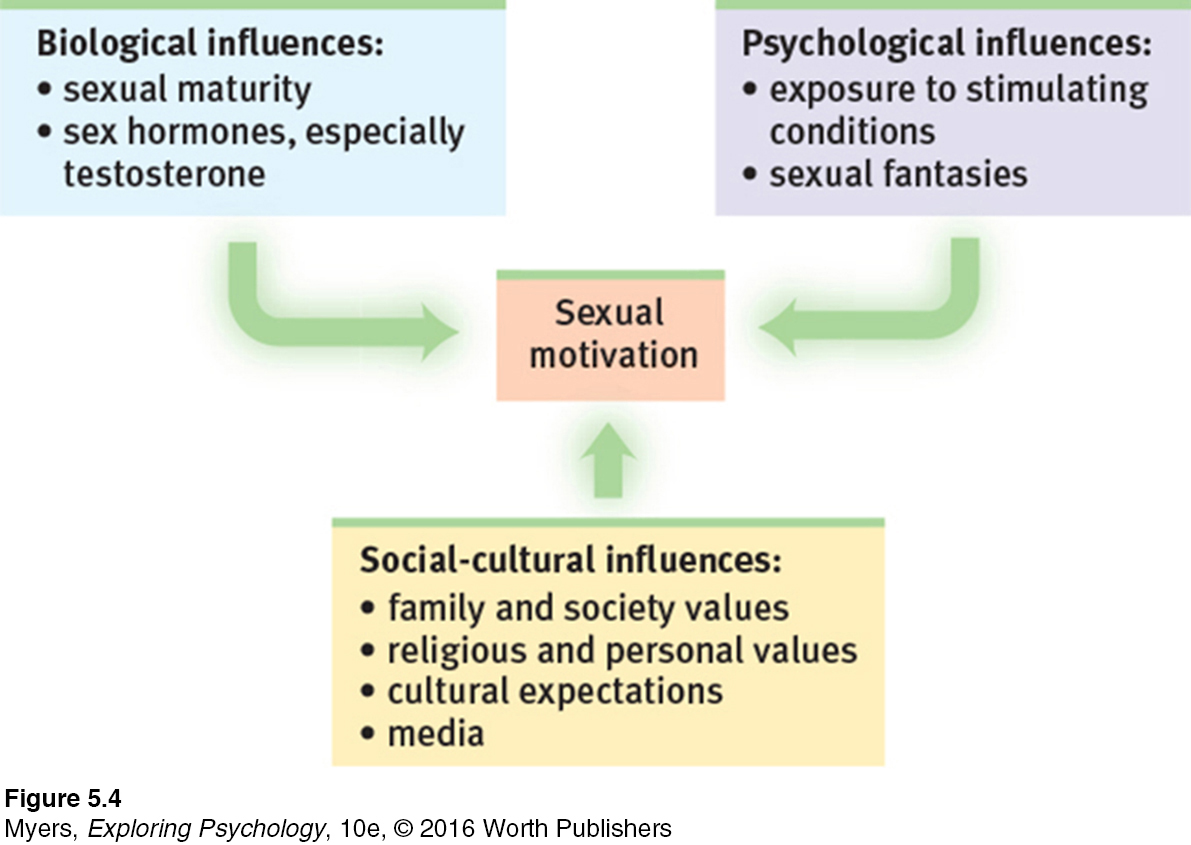

Biological factors powerfully influence our sexual motivation and behavior. Yet the wide variations over time, across place, and among individuals document the great influence of psychological factors as well (FIGURE 5.4). Thus, despite the shared biology that underlies sexual motivation, 281 expressed reasons for having sex ranged widely—

External Stimuli

Men and women become aroused when they see, hear, or read erotic material (Heiman, 1975; Stockton & Murnen, 1992). In 132 experiments, men’s feelings of sexual arousal have much more closely mirrored their (more obvious) genital response than have women’s (Chivers et al., 2010).

People may find sexual arousal either pleasing or disturbing. (Those who wish to control their arousal often limit their exposure to such materials, just as those wishing to avoid overeating limit their exposure to tempting cues.) With repeated exposure, the emotional response to any erotic stimulus often lessens, or habituates. During the 1920s, when Western women’s rising hemlines first reached the knee, an exposed leg was a mildly erotic stimulus.

Can exposure to sexually explicit material have adverse effects? Research has indicated that it can:

Rape acceptance Depictions of women being sexually coerced—

and liking it— have increased viewers’ belief in the false idea that women enjoy rape, and have increased male viewers’ willingness to hurt women (Malamuth & Check, 1981; Zillmann, 1989). Devaluing partner Viewing images of sexually attractive women and men may also lead people to devalue their own partners and relationships. After male college students viewed TV or magazine depictions of sexually attractive women, they often found an average woman, or their own girlfriend or wife, less attractive (Kenrick & Gutierres, 1980; Kenrick et al., 1989; Weaver et al., 1984).

Diminished satisfaction Viewing X-

rated sex films has similarly tended to reduce people’s satisfaction with their own sexual partner (Zillmann, 1989). Perhaps reading or watching erotica’s unlikely scenarios may create expectations that few men and women can fulfill.

Imagined Stimuli

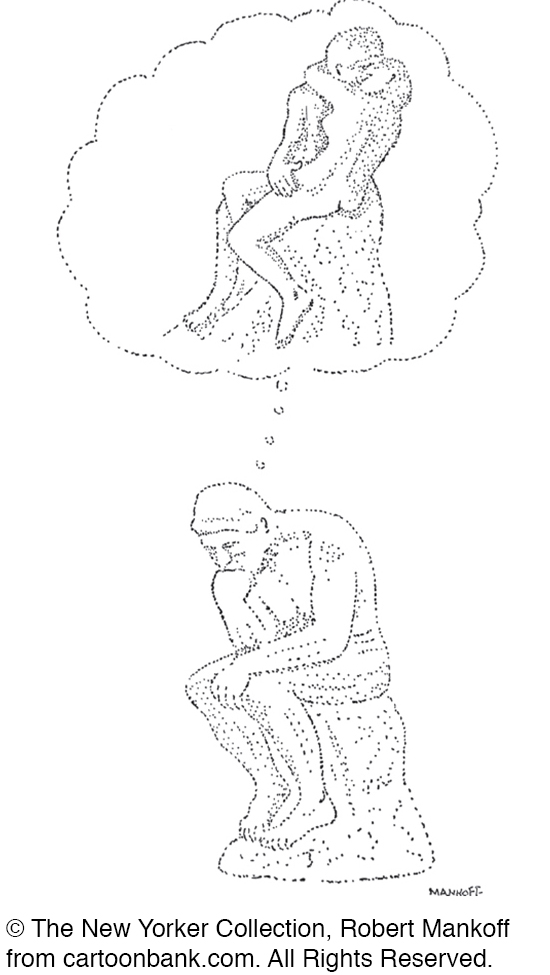

The brain, it has been said, is our most significant sex organ. The stimuli inside our heads—

Wide-

186

RETRIEVE IT

Question

qL3LU2jj0tKt1uK31Nxh5gUVU3hUw1l7HyMf2vCnC2DZmlhp14CnvuC+GB1oVwDjp0fyCpOJiOgru/EIjpvHObBbdDzSdI6goT2iV13hxGmZY43Zwz537Y/+abHDZ3Se+OjZ3vv1DKE=Teen Pregnancy

5-

Compared with European teens, American teens have a higher rate of STIs and also of teen pregnancy (Call et al., 2002; Sullivan/Anderson, 2009). What environmental factors contribute to teen pregnancy?

Minimal communication about birth control Many teenagers are uncomfortable discussing contraception with their parents, partners, and peers. Teens who talk freely with parents, and who are in an exclusive relationship with a partner with whom they communicate openly, are more likely to use contraceptives (Aspy et al., 2007; Milan & Kilmann, 1987).

Guilt related to sexual activity Among sexually active 12-

Alcohol use Most sexual hookups (casual encounters outside of a relationship) occur among people who are intoxicated, with an impaired ability to give and comprehend consent (Fielder et al., 2013; Garcia et al., 2013). Those who use alcohol prior to sex are less likely to use condoms (Kotchick et al., 2001). By depressing the brain centers that control judgment, inhibition, and self-

“Condoms should be used on every conceivable occasion.”

Anonymous

social script culturally modeled guide for how to act in various situations.

Mass media norms of unprotected promiscuity Perceived peer norms influence teens’ sexual behavior (van de Bongardt et al., 2015). Teens attend to other teens, who, in turn, are influenced by popular media. Media help write the social scripts that affect our perceptions and actions. So what sexual scripts do today’s media write on our minds? Sexual content appears in approximately 85 percent of movies, 82 percent of television programs, 59 percent of music videos, and 37 percent of music lyrics (Ward et al., 2014). Twenty percent of middle school students, and 44 percent of 18-

Media influences can either increase or decrease sexual risk taking. One study asked more than a thousand 12-

187

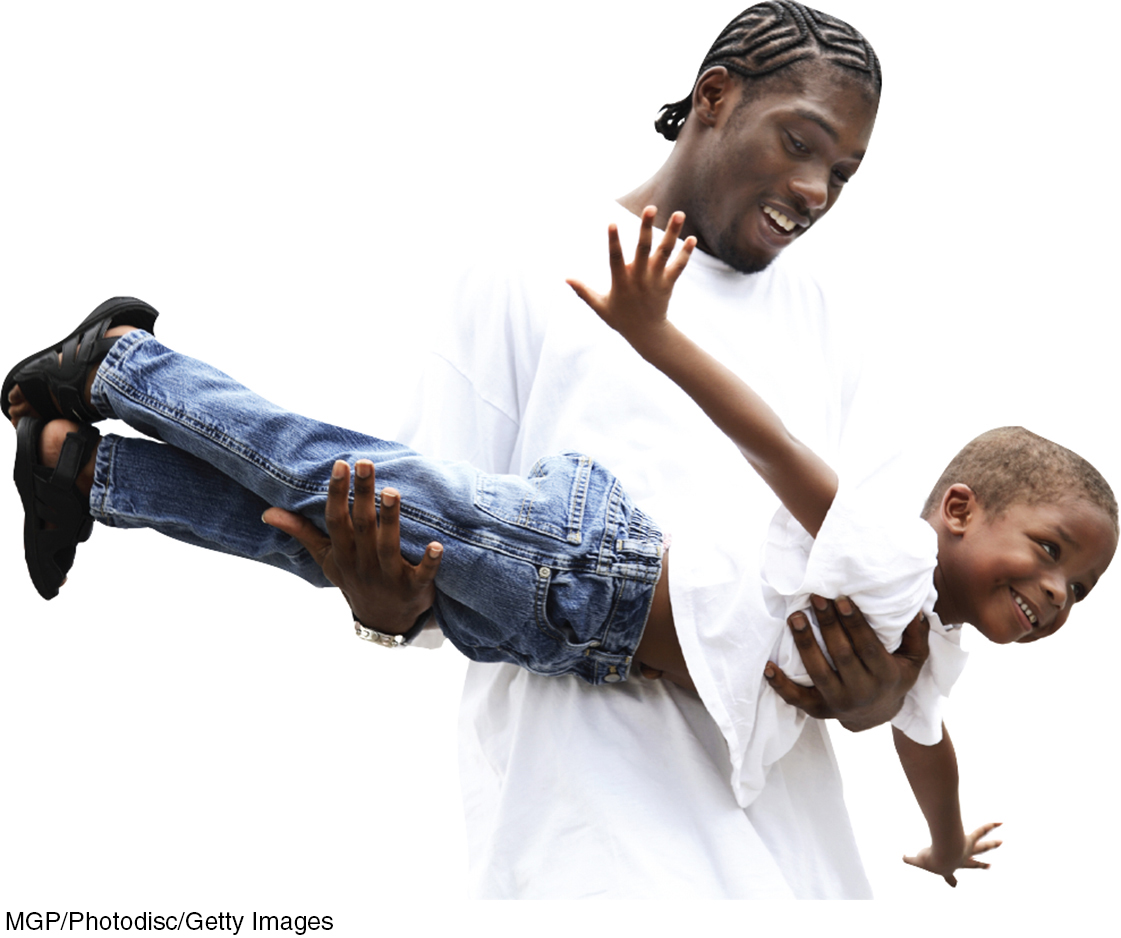

Later sex may pay emotional dividends. One national study followed participants to about age 30. Even after controlling for several other factors, those who had later first sex reported greater relationship satisfaction in their marriages and partnerships (Harden, 2012). Several other factors also predict sexual restraint:

High intelligence Teens with high rather than average intelligence test scores more often delayed sex, partly because they considered possible negative consequences and were more focused on future achievement than on here-

and- now pleasures (Halpern et al., 2000). Religious engagement Actively religious teens have more often reserved sexual activity for adulthood (Hull et al., 2011; Lucero et al., 2008).

Father presence In studies that followed hundreds of New Zealand and U.S. girls from age 5 to 18, a father’s absence was linked to sexual activity before age 16 and to teen pregnancy (Ellis et al., 2003). These associations held even after adjusting for other adverse influences, such as poverty. Close family attachments—

families that eat together and where parents know their teens’ activities and friends— also predicted later sexual initiation (Coley et al., 2008). Participation in service learning programs Several experiments have found that teens volunteering as tutors or teachers’ aides, or participating in community projects, had lower pregnancy rates than were found among comparable teens randomly assigned to control conditions (Kirby, 2002; O’Donnell et al., 2002). Researchers are unsure why. Does service learning promote a sense of personal competence, control, and responsibility? Does it encourage more future-

oriented thinking? Or does it simply reduce opportunities for unprotected sex?

RETRIEVE IT

Question

GMNEjorXefS3/qAznMUThLZYC64AdTQ8PgckkdCop8J6Xay09+P3CSim1+kGyGGM3mwEiVif7XtAg3vEkkM1gyLmlM9zg+wmlC8JCzSb4r6wFSTPEQZdD2BFTZFXuT59m038CQ==Sexual Orientation

5-

sexual orientation an enduring sexual attraction toward members of one’s own sex (homosexual orientation), the other sex (heterosexual orientation), or both sexes (bisexual orientation).

We express the direction of our sexual interest in our sexual orientation—our enduring sexual attraction toward members of our own sex (homosexual orientation), the other sex (heterosexual orientation), or both sexes (bisexual orientation). Cultures vary in their attitudes toward same-

In one British survey, of the 18,876 people contacted, 1 percent were asexual, having “never felt sexually attracted to anyone at all” (Bogaert, 2004, 2006b; 2012). People identifying as asexual are, however, nearly as likely as others to report masturbating, noting that it feels good, reduces anxiety, or “cleans out the plumbing.”

Sexual Orientation: The Numbers

How many people are exclusively homosexual? About 10 percent, as the popular press has often assumed? Or 20 percent, as the average American estimated in a 2013 survey (Jones et al., 2014)? According to more than a dozen national surveys in Europe and the United States, a better estimate is about 3 or 4 percent of men and 2 percent of women (Chandra et al., 2011; Herbenick et al., 2010; Savin-

188

Survey methods that absolutely guarantee people’s anonymity reveal another percent or two of nonheterosexual people (Coffman et al., 2013). Moreover, people in less tolerant places are more likely to hide their sexual orientation. About 3 percent of California men express a same-

Fewer than 1 percent of people—

What does it feel like to have same-

In tribal cultures in which homosexual behavior is expected of all boys before marriage, heterosexuality nevertheless persists (Hammack, 2005; Money, 1987). As this illustrates, homosexual behavior does not always indicate a homosexual orientation.

Facing such reactions, some individuals struggle with their sexual attractions, especially during adolescence and if feeling rejected by parents or harassed by peers. If lacking social support, nonheterosexual teens may experience lower self-

Today’s psychologists therefore view sexual orientation as neither willfully chosen nor willfully changed. “Efforts to change sexual orientation are unlikely to be successful and involve some risk of harm,” declared a 2009 American Psychological Association report. Sexual orientation in some ways is like handedness: Most people are one way, some the other. A very few are truly ambidextrous. Regardless, the way one is endures.

This conclusion is most strongly established for men. Women’s sexual orientation tends to be less strongly felt and potentially more fluid and changing (Chivers, 2005; Diamond, 2008; Dickson et al., 2013). In general, men are sexually simpler. Their lesser sexual variability is apparent in many ways (Baumeister, 2000). Compared with men, women’s sexual drive and interests are more flexible and varying. Women, for example, more often prefer to alternate periods of high sexual activity with periods of almost none (Mosher et al., 2005). In their pupil dilation and genital responses to erotic videos, and in their implicit attitudes, heterosexual women exhibit more bisexual attraction than do men (Rieger & Savin-

Origins of Sexual Orientation

189

So, our sexual orientation is something we do not choose and (especially for males) cannot change. Where, then, do these preferences come from? See if you can anticipate the conclusions that have emerged from hundreds of research studies by responding Yes or No to the following questions:

Is homosexuality linked with problems in a child’s relationships with parents, such as with a domineering mother and an ineffectual father, or a possessive mother and a hostile father?

Does homosexuality involve a fear or hatred of people of the other sex, leading individuals to direct their desires toward members of their own sex?

Is sexual orientation linked with levels of sex hormones currently in the blood?

As children, were most homosexuals molested, seduced, or otherwise sexually victimized by an adult homosexual?

The answer to all these questions has been No (Storms, 1983). In a search for possible environmental influences on sexual orientation, Kinsey Institute investigators interviewed nearly 1000 homosexuals and 500 heterosexuals. They assessed nearly every imaginable psychological cause of homosexuality—

And consider this: If “distant fathers” were more likely to produce homosexual sons, then shouldn’t boys growing up in father-

The bottom line from a half-

Same-

sex behaviors in other species Gay-

straight brain differences Genetic influences

Prenatal influences

Note that the scientific question is not “What causes homosexuality?” (or “What causes heterosexuality?”) but “What causes differing sexual orientations?” In pursuit of answers, psychological science compares the backgrounds and physiology of people whose sexual orientations differ.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Naturalistic Observation for a helpful tutorial animation.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Naturalistic Observation for a helpful tutorial animation.

SAME-

190

GAY-

It should not surprise us that brains differ with sexual orientation. Remember, everything psychological is simultaneously biological. But when did the brain difference begin? At conception? During childhood or adolescence? Did experience produce the difference? Or was it genes or prenatal hormones (or genes via prenatal hormones)?

LeVay does not view this cell cluster as an “on-

Since LeVay’s discovery, other researchers have reported additional gay-

“Gay men simply don’t have the brain cells to be attracted to women.”

Simon LeVay, The Sexual Brain, 1993

GENETIC INFLUENCES Evidence indicates a genetic influence on sexual orientation. “Homosexuality does appear to run in families,” noted Brian Mustanski and Michael Bailey (2003). Researchers have speculated about possible reasons why “gay genes” might exist in the human gene pool, given that same-

A fertile females theory suggests that maternal genetics may also be at work (Bocklandt et al., 2006). Homosexual men tend to have more homosexual relatives on their mother’s side than on their father’s (Camperio-

191

Studies of twins also indicate that genes influence sexual orientation. Identical twins (who have identical genes) are somewhat more likely than fraternal twins (whose genes are not identical) to share a homosexual orientation (Alanko et al., 2010; Lángström et al., 2010). However, because sexual orientation differs in many identical twin pairs (especially female twins), other factors must also play a role.

In genetic studies of fruit flies, researchers have altered a single gene and changed the flies’ sexual orientation and behavior (Dickson, 2005). During courtship, females acted like males (pursuing other females) and males acted like females (Demir & Dickson, 2005). With humans, it’s likely that multiple genes, possibly in interaction with other influences, shape sexual orientation. A genome-

PRENATAL INFLUENCES Twins share not only genes, but also a prenatal environment. Two sets of findings indicate that the prenatal environment matters.

First, in humans, a critical period for fetal brain development seems to be the second trimester (Ellis & Ames, 1987; Garcia-

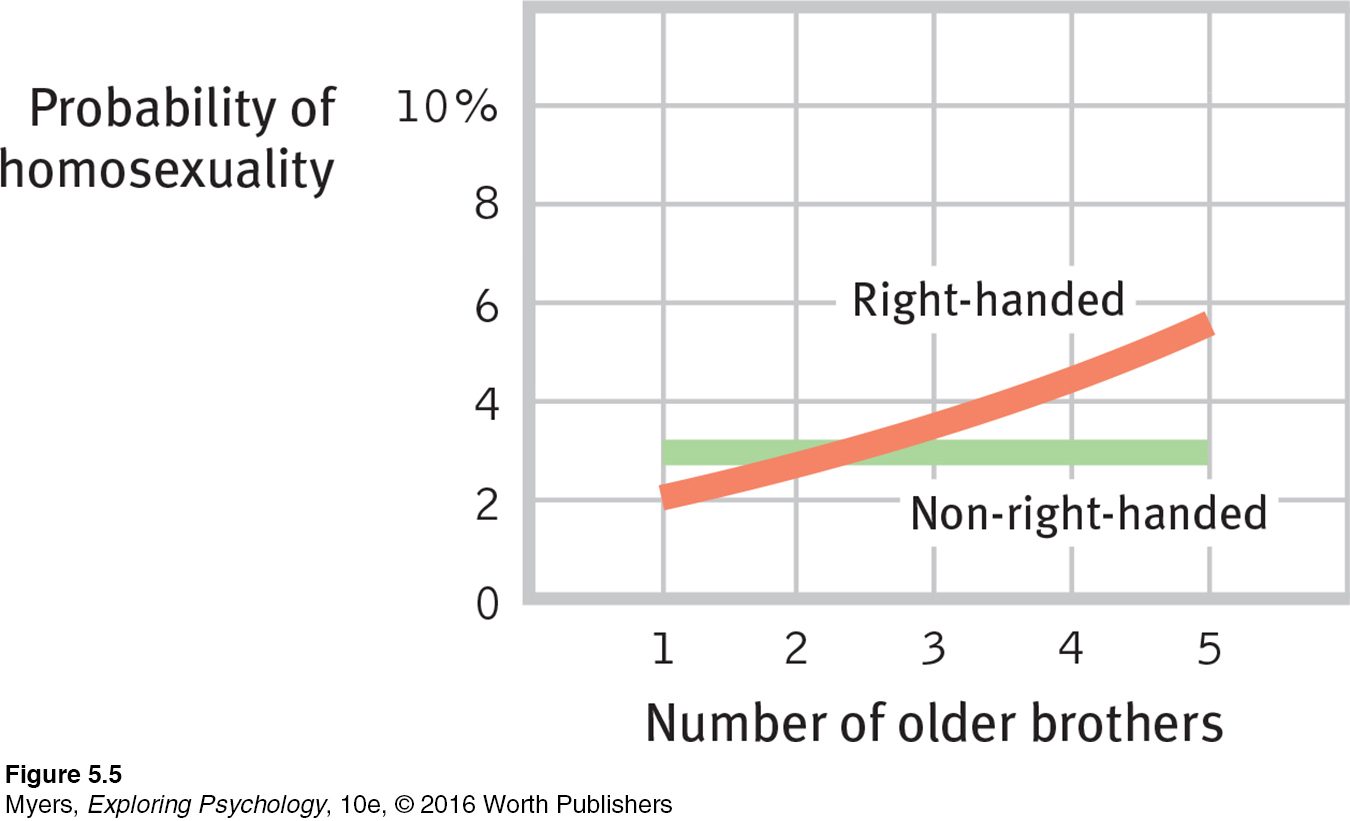

Second, the mother’s immune system may play a role in the development of sexual orientation. Men who have older brothers are somewhat more likely to be gay—

“Modern scientific research indicates that sexual orientation is . . . partly determined by genetics, but more specifically by hormonal activity in the womb.”

Glenn Wilson and Qazi Rahman, Born Gay: The Psychobiology of Sex Orientation, 2005

Gay-Straight Trait Differences

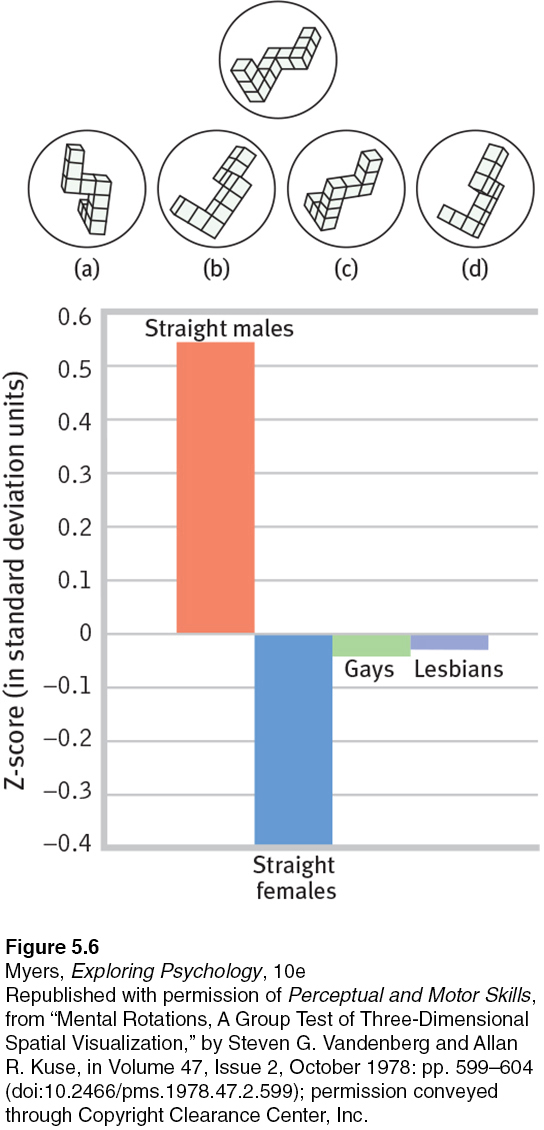

On several traits, gays and lesbians appear to fall midway between straight females and males (TABLE 5.1 below; see also LeVay, 2011; Rahman & Koerting, 2008). Gay men tend to be shorter and lighter than straight men—

Gay-

Biological Correlates of Sexual Orientation

| Gay- |

| Sexual orientation is part of a package of traits. Studies— |

|

| On average (the evidence is strongest for males), results for gays and lesbians fall between those of straight men and straight women. Three biological influences— |

| Brain differences |

|

| Genetic influences |

|

| Prenatal influences |

|

For an 8-

For an 8-

* * *

Taken together, the brain, genetic, and prenatal findings offer strong support for a biological explanation of sexual orientation (LeVay, 2011; Rahman & Koerting, 2008). Although “much remains to be discovered,” concludes Simon LeVay (2011, p. xvii), “the same processes that are involved in the biological development of our bodies and brains as male or female are also involved in the development of sexual orientation.”

“There is no sound scientific evidence that sexual orientation can be changed.”

UK Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2009

192

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Q2ubrY8ItZBxxErhdiqd2NNa9FyycBL8XLu+TehLWDQQxGB9UWfIkyTs1qc26DspKBTPaUUytzWBxTP10buwWLSuErZiizEpV3/te4G5cPPRuwkmU2kFvMGef6xd3CEJHlsuWDEQl+dn/jtPMscHRNRh5/n9N5DkfCzr1w==An Evolutionary Explanation of Human Sexuality

5-

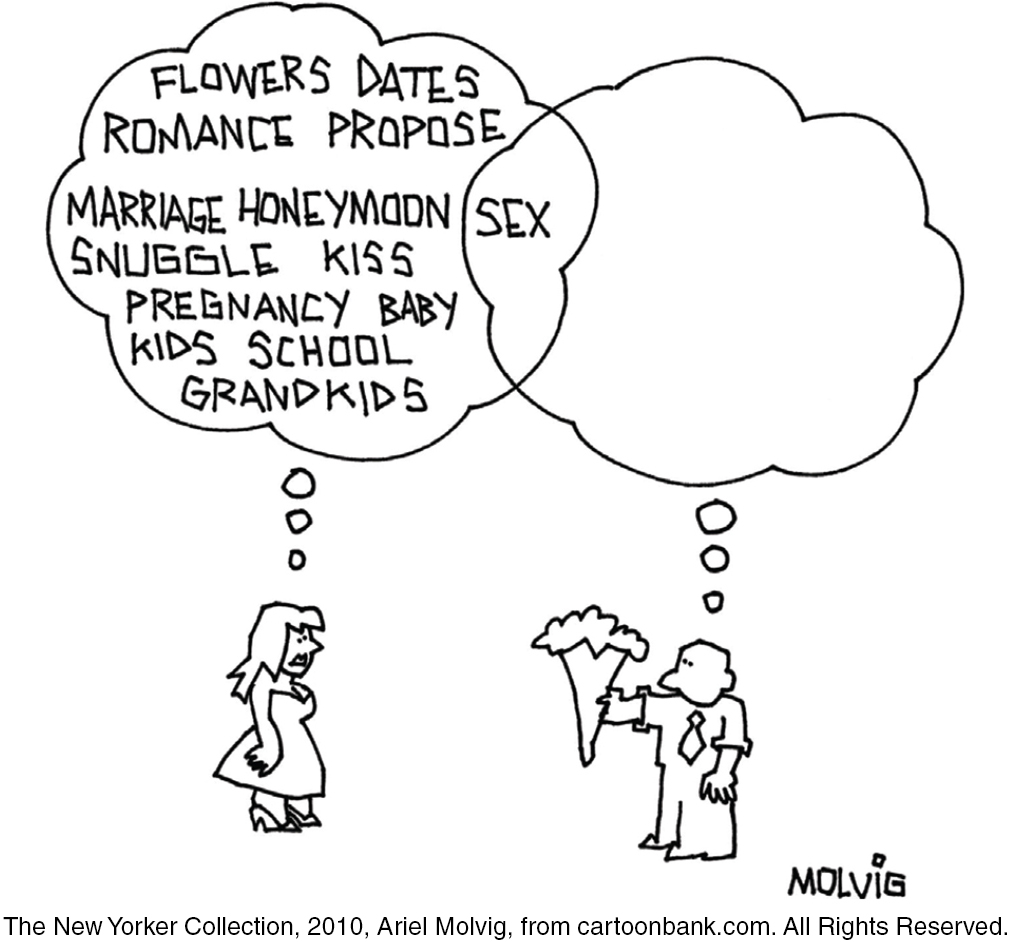

Having faced many similar challenges throughout history, males and females have adapted in similar ways: We eat the same foods, avoid the same predators, and perceive, learn, and remember similarly. It is only in those domains where we have faced differing adaptive challenges—

Male-Female Differences in Sexuality

And differ we do. Consider sex drives. Both men and women are sexually motivated, some women more so than many men. Yet, on average, who thinks more about sex? Masturbates more often? Initiates more sex? Views more pornography? The answers worldwide—

193

And there are other sexuality differences between males and females (Hyde, 2005; Petersen & Hyde, 2010; Regan & Atkins, 2007). To see if you can predict some of these differences, take the quiz in TABLE 5.2.

Predict the Responses Researchers asked samples of U.S. adults whether they agreed or disagreed with the following statements. For each item below, give your best guess about the percentage who agreed with the statement.

| Statement | Percentage of males who agreed | Percentage of females who agreed |

| 1. If two people really like each other, it’s all right for them to have sex even if they’ve known each other for a very short time. | _____________ | _____________ |

| 2. I can imagine myself being comfortable and enjoying “casual” sex with different partners. | _____________ | _____________ |

| 3. Affection was the reason I first had intercourse. | _____________ | _____________ |

| 4. I think about sex every day, or several times a day. | _____________ | _____________ |

|

Sources: (1) Pryor et al., 2005; (2) Bailey et al., 2000; (3 and 4) Research from Laumann et al., 1994. |

||

(ANSWERS)

To listen to experts discuss evolutionary psychology and sex differences, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Evolutionary Psychology and Sex Differences.

To listen to experts discuss evolutionary psychology and sex differences, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Evolutionary Psychology and Sex Differences.

Compared with lesbians, gay men (like straight men) report more responsiveness to visual sexual stimuli, and more concern with their partner’s physical attractiveness (Bailey et al., 1994; Doyle, 2005; Schmitt, 2007; Sprecher et al., 2013). Gay male couples also report having sex more often than do lesbian couples (Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007). And they report more interest in uncommitted sex. Although men are roughly two-

“It’s not that gay men are oversexed; they are simply men whose male desires bounce off other male desires rather than off female desires.”

Steven Pinker, How the Mind Works, 1997

Natural Selection and Mating Preferences

Natural selection is nature selecting traits and appetites that contribute to survival and reproduction. Evolutionary psychologists use this principle to explain how men and women differ more in the bedroom than in the boardroom. Our natural yearnings, they say, are our genes’ way of reproducing themselves. “Humans are living fossils—

Why do women tend to be choosier than men when selecting sexual partners? Women have more at stake. To send her genes into the future, a woman must—

194

The data are in, say evolutionists: Men pair widely; women pair wisely. And what traits do straight men find desirable? Some, such as a woman’s smooth skin and youthful shape, cross place and time, and they convey health and fertility (Buss, 1994). Mating with such women might increase a man’s chances of sending his genes into the future. And sure enough, men feel most attracted to women whose waists (thanks to their genes or their surgeons) are roughly a third narrower than their hips—

There is a principle at work here, say evolutionary psychologists: Nature selects behaviors that increase the likelihood of sending one’s genes into the future. As mobile gene machines, we are designed to prefer whatever worked for our ancestors in their environments. They were genetically predisposed to act in ways that would leave grandchildren. Had they not been, we wouldn’t be here. As carriers of their genetic legacy, we are similarly predisposed.

Critiquing the Evolutionary Perspective

5-

Most psychologists agree that natural selection prepares us for survival and reproduction. But critics say there is a weakness in evolutionary psychology’s explanation of our mating preferences. Let’s consider how an evolutionary psychologist might explain the findings in a startling study (Clark & Hatfield, 1989), and how a critic might object.

Participants were approached by a “stranger” of the other sex (someone working for the experimenter). The stranger remarked, “I have been noticing you around campus. I find you to be very attractive,” and then sometimes asked, “Would you go to bed with me tonight?” What percentage of men and women do you think agreed to this offer? The evolutionary explanation of sexuality predicts that women will be choosier than men in selecting their sexual partners and will be less willing to hop in bed with a complete stranger. In fact, not a single woman agreed—

Or did it? Critics note that evolutionary psychologists start with an effect—

Other critics ask why we should try to explain today’s behavior based on decisions our distant ancestors made thousands of years ago. Don’t cultural expectations also bend the genders? Alice Eagly and Wendy Wood (1999; Eagly, 2009) point to the smaller behavioral differences between men and women in cultures with greater gender equality, for example. Such critics believe social learning theory offers a better, more immediate explanation for these results. Women learn social scripts—their culture’s guide to how people should act in certain situations. By watching and imitating others in their culture, they may learn that sexual encounters with strangers can be dangerous, and that casual sex may not offer much sexual pleasure (Conley, 2011). This alternative explanation of the study’s effects proposes that women react to sexual encounters in ways that their modern culture teaches them. Similarly, men are influenced by social scripts teaching the lesson that “real men” take advantage of every opportunity to have sex.

195

A third criticism focuses on the social consequences of accepting an evolutionary explanation. Are heterosexual men truly hard-

To experience a demonstration and explanation of evolutionary psychology and mating preferences, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Dating and Mating.

To experience a demonstration and explanation of evolutionary psychology and mating preferences, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Dating and Mating.

Evolutionary psychologists agree that much of who we are is not hard-

Evolutionary psychologists also agree with their critics that some traits and behaviors, such as suicide, are hard to explain in terms of natural selection (Barash, 2012; Confer et al., 2010). But they ask us to remember evolutionary psychology’s scientific goal: to explain behaviors and mental traits by offering testable predictions using principles of natural selection. We can, for example, scientifically test hypotheses such as this: Do we tend to favor others to the extent that they share our genes or can later return our favors? (The answer is Yes.) They also remind us that studying how we came to be need not dictate how we ought to be. Understanding our tendencies can help us overcome them.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

lZsqfQci5lLnh2SUtPQWZPCxsS+vo452IjrQG6CAwb1AM3L/zZrpi+wxocbE4Of3AJgofa73WdDUgDRjPU1YsUPn3NYpBf+20lzhLa7yA3az8/9NufxFh49FWeGFkAnx15fYjDiM2GcT1/v9wt9v4z0pthp0BdzHQuestion

achn8C72CHOvpCsl4vt9WYwW79d1r90eBM+9qEAhnnDYlPi6s+cMmqNHpElRs7fh3XnZnCxaMjr6j4Gof2Jm1f/A4J3nwNb66xl/Px2oIa33sXUxAynhJ+PXW3vQt33gzWjGC1kNT/6yi+xit6mkn5GZlYYMwAGVrF0HmU3BrkdlnU/rSocial Influences on Human Sexuality

5-

Human sexuality research does not aim to define the personal meaning of sex in our own lives. We could know every available fact about sex—

Surely one significance of such intimacy is its expression of our profoundly social nature. One study asked 2035 married people when they started having sex (while controlling for education, religious engagement, and relationship length). Those whose relationship first developed to a deep commitment, and then included sex, not only reported greater relationship satisfaction and stability but also better sex than those who had sex very early in their relationship (Busby et al., 2010; Galinsky & Sonenstein, 2013). For both men and women, but especially for women, orgasm occurs more often (and with less morning-

196

Sex is a socially significant act. Men and women can achieve orgasm alone, yet most people find greater satisfaction—

Reflections on the Nature and Nurture of Sex, Gender, and Sexuality

Our ancestral history helped form us as a species. Where there is variation, natural selection, and heredity, there will be evolution. Our genes form us. This is a great truth about human nature.

But our culture and experiences also form us. If their genes and hormones predispose males to be more physically aggressive than females, culture can amplify this gender difference through norms that shower benefits on macho men and gentle women. If men are encouraged toward roles that demand physical power, and women toward more nurturing roles, each may act accordingly. By exhibiting the actions expected of those who fill such roles, men and women shape their own traits. Presidents in time become more presidential, servants more servile. Gender roles similarly shape us.

In many modern cultures, gender roles are merging. Brute strength is becoming increasingly less important for power and status (think Mark Zuckerberg and Hillary Clinton). From 1965 to 2013, women soared from 9 to 47 percent of U.S. medical students (AAMC, 2014). In 1965, U.S. married women devoted eight times as many hours to housework as did their husbands; by 2011 this gap had shrunk to less than twice as many (Parker & Wang, 2013). Such swift changes signal that biology does not fix gender roles.

If nature and nurture jointly form us, are we “nothing but” the product of nature and nurture? Are we rigidly determined?

We are the product of nature and nurture, but we are also an open system. Genes are all-

We can’t excuse our failings by blaming them solely on bad genes or bad influences. In reality, we are both the creatures and the creators of our worlds. So many things about us—

REVIEW Human Sexuality

Learning Objectives

197

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

zDUBXb0PHlfr2FNWn9ux5nwfeXl7lMIl4cLZE3/w1/KH+wJwU2pdvOHSXaDD1r7x08kw6A33E6K88LDLz0Qtj7BrH49De8CpMma8Zwbfr6B7lLmTrKg99jiBa6lA8eC28lf0xt9KWQtpiWs39xitVdeJfcc2NRpwC73LjwScc8w0zekXgf1Ib3gBbyGY6ezHNA7SgmYLQiVNTmXIJZGYZgXbrHI=Question

4E0gm5t9xyEzQlcD63rRSlQBxgamg+/1WZbByIDfbU9twxUWzagLexW7Uet50SeGHHpJtepV3loICEqTuSjRePoPwALzqS0milXZ6heAW8NLh7H46MvfCGud6+r/k5tfSHaXANmJoIEnNI62OuZKMPcB/Ox2irbXEKbwe7A45C/QansPNZJy/VuG7N4oH+7Tz2ghhNb+ICQcYAXT2pROl34M/7/Ws8fWOUC3XtiEh9Tn0U6txAJz8V2amhgcV4PQW07Qe8Dpq05cdc9kjLEDlZHlmFM=Question

6LlSTk0/36glPRoH3zEC5Z+BvlBwxJ4lusDKslra2La2TePZ/ktXx5MSTTleZ+ua8rN47XWiwL4f1A8fbJQAtJgMkTajWdnmTHCjvBUVWZZXZ04WrcXuXMY5P7V5DlvomCHrM/3gdfJvZYZNVP4xsOv2D0N/fhFUAoCRDOSOAChAveFVzYiEmWoBnkG8A8FD0X9QafPG6kbbF1KPOOnihE1owDesjQnYQuestion

2X4qGwoEoMD1U+xmnRLduS+Vs6Fi2vEHxf8NVeAEDAP6xvojry3zooqGU/p2WH4IjhRssDX1hUswFo0kJfqsPTxOejUeJPnJBrsFkRS5ePScXuVVtl9kX8MvMBUmX0gmfyLz2ilQY++vgDuIjEerp6ygCAR74GXJQWJsJdB0RbjtYIx/49sKtbS0FPPkpaYtSz4Hwib714ugJrER/XllwfQmN68gBEpDn5tYuu/RQbUI8vtJQuestion

qXq4WY/qeHxbKca1z8DJxITvClyLv7eX7mYAp8hCqY7zogzLpeCsP+uvQOGHj0131TCq3tadGiExe78AsYfysyAxF8+Pit1+LKYP0rjc+ghqoMDZ1EjgMwxwUMz/T71bVN0svnhsAGmcVJIuzMCMtW+fPu/ah20S29bO3dgBAogcNLY88Hp8NQf5an9dnIWc58ue/uw9ADxahjTZr/GyVaAKJ8DGNqG5bKuGSrNgwyXY9Fv1a98ZNL6+ST6WTDggQuestion

6NjClEM9VH/dCD+FpPFmXgKLBC/d4SL4uRdGuH3yN1BbE2eAl0yjb4T/E0GhaS/gPFVYL1AcRsY94rWn36C4OukZuSqyrI0fR0yOgsWbrjw+GNlz7vw6hmwDOEHdf9UAcr0RIygalP/B7cHC/uWTfv2nRpbCWGmLJqrtRYEZU0dmFMEE3fv/hDqr60EsIqvxW3lJEpfuW+8pXFAH7TcLFkxyAAMkplRSQuestion

ANb6r4qQ2vZOQvgGD1ojzB2+K2x0Z0raaJQgKEuZP0o5gbcptp/SOXd5uNp66G97Dyq7MYsu42G+PyiDdtSj2bCmhBO6rhp/D3r/Ft+isRmaW0WPHBOHU405OpXzI2FBB+4mNfLpjL/44SFArEmNITf3Z729s4ViNQzLWAVGuSvhyspH65KyGEFEchJTnWcGGo49AwCWpN8r8RqE8adEtXX3Y+TXuXELOd1OrF6XNoA7re/XwqHiRsSNp6oQD9O8ouoeo2j45qwS7mq/rLW5/JfqDB4kLqZgP+bS4/LIKNTc8yiHg6jb8p0YeoKQT3DzRvKufSfDnS6sn4pSZBFMEADGoghUNjT+1pzDpqLdYkE=Question

qd9bmp77PNlkjrxIUQ0BbAWiVCWzt4WBra9nrC5vngis+tSw3nCNmmsCc0XRsw3okOA20ZojKtPUWaCKTdOeaSXAwfWE7o8C/5OXYYb/+UAbjM7WEZSVF19xRjs9cvMF6SGqJ0KY+WJvKZvnP6NGsz8EJSlJS2qmHbFbOYfIB2KAd3hwO3vZwDFT59D+WyYQko/PictX8o9Jpx+w98cF7Ux5DbuqXwUtbD3TDjQP+sYsGz0E0BiaOC3z5dlJcWOgx5f1jQzeq7PSrLHuva8j/1DpwSQ/PSCb7EpjWiC/kjJ1FFsjb9Zsms10u+be0pEEQuestion

Yz19U3pkB5Z33ZH+5oHeFEKKSVsllkjhfcUKAHGQD0dzGrn6CXBhG8z7Zw/EUmOkNVBo+1BRBFy8dDGugg6nfMt2k3IKH71WWflraxTPPOjeTaW9A+jFvS6YItyZ2cJ33poMd9T9b8mttHbAry4Nwgggf8NeS3Y/fg6CXTsuAB4Oq7SPcXxmnuELkult61NuoMI1PBfF3HnalbZF3x1kIwN8RZginAufy/bERcn1S4T6QSggIWMPN7Zk9tcRwo50FG5/BWJa1Ody1vwHXGPjDYp63V2xscBrkhSm8cOATnHAc/YQOL7SlqKYCB1+kZMmgekXShi1zH+n8TJHTerms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

OIccN7O/s/VVRC61ZDhKJHoF9HLbuxCjtMgTU75veT+cyBgEmT5tXqQfZnl0BlRxilVyCiXrOvSQz/MmMgQpUIqOOSeZ8gNySnaQkPiCyKu4O+h+1X4DDcBANsOQEVu1dMA0GymX1PvCxU1QLZjY+dBFxmnLr7lQbOMiMy78f3sBpZpvTJQA6aqsOR1sCW0qskAvFM2liebCIs/nUHRxkLK0cu9tqqJFEMulszgLdwCzWjP2pgO1gV00We4BaKOBPUtz6mpjN+JJUIxSY8djf4UOwzNtKhbPkHwDHq/78NOPlvM5OQnMb94BZJnLywBSjYwAy5h2KDIfuafZ/5wSiCcne8v2K2hOzPeQ6HaU7gGyUK9ztUFuEmIizBzzoZoeK0uH35JfhknwXrJp0vLCTPDn+MpH4YAvtl4a+oyalNc5eKtCOt24WqXOqpt1xodC2Z2yuGWchJIpZov9SiyKVaJHkVDbLIG5etJpxeP/RIdL86VdGvOqH7umBxJSqhxX5Lzn30N6farMJzq9VFGymEsTzjVAPSF+wrL3cgsDSQadVebEXS7sxcbxlTSbo6afTP9u0/nQHAtwrrHfl35rIQJ04RjPyPHHTlKuKlldPgCqq5ZiWxpWa2QNB7NeOdas1JkjZ1mRI8UNW3BjF+IUh6uWByjgBD76a+ESjPNx1dcAQf9JWnpyrMLLnXOmf9cT1HWxeYkWrsr4Ik6P8cWps/ArmUdnnbFwUUEQB1XvD3UEIrAHP5Hh5T8/nIzBoRhS4Zb0JG9jlX8NORoxbDJBhTcaZE6xlSFa5kDHmH3Ue9SpgjMcKo/8rOZR2Qx60Gm11eP0hGTTln7D38FaYP5XOnCafuS1fBqkMvs5907saS0GhKMG621tcGKR7gz+wIoUfTThBlQGpHcex+hbWcsNNhlch1DYS94yGu85VaYbmFAn5Tl+Nj0S0QpH3PO+14+UueoLFD01wfhBxniGGqnE5IuXVdSG4isKR9FRUTT4ev6rX3fG/zR8CVIU+CVUpkivrxsF6fsNHczvv9Vv3VT7k+pqjQgpgTWswBjyBe0Cg7BExOnmR3ZLNrmXf0Yn0nki3me5Nvp7XW892994Oh/3fO/npCkHaXt3nb4K/MHzqhJZZQxgrhWs1RUkM2hMlNzzTkECRv6n/briRG98YffQHxOyXFCxkxaQzfCGfLSmCdUndSLP+vXC+iDH9l88pAcyIeB8lXkxViW3yHyyIjiweVTT79QzPplixfHXMedJiPw8W1bkJ0mWZB6WAWpWkF5NyGT5EPUDYBHbGJ2Cgo/+5L0OudxWIZjDbCTOaSnLzmtV0PcNARldH0rTlOkwxDW3d8xMxw0rWJaGNDCbBMaRHPX2PYgTt0NGyVPwK338aZvpCbZ97CZupMh30ebDyzhQantAGirh6EgO/xs/x948PmdV0pReoRvgwx7R9/MO9J/sqqLvnDCSM95HjG486Z64038JtY+AtZW0vtpfB1sJVW5MCd0H29Y+wcsdtR0bzKdAb+uJl3v2eC3Gv8fPPFY1TFfZrVEDiU6dXGMMiY5PipRPALedPvRhrRGORkD8gr2Ysm3srkzAWlV2RN/JPYJGBSe10NZKQTigMOeP7IFxldZIyGf3OWgNQ04F02TG9KepP1qWrc17WuUZz2Dcm651K64LGBrsKNG4s2a+WD83QniCznp3+uRgp1T2antG4g5YjCzPbzMR45O+uYEmhMHglmAyq5dw3XehJ9qi8OXw6rH7c2FafVwpa3y2oYtvdOqh1okHaFn5VCQcchPq3rPP7PdoSEgCxCXsvJJDCgJ5CGrGhah7pkgfwNImLcDU7oGem5L5R3evaNtl5xgUeAyExmkr4a246zmQNQ+Gt2Ipv3NVH5XJF8OHDTuODjIOKqvkGabrjFUuuGaSs6WZLLHMMj0x/xLTuhZlWMvslwHRJCtKbjgbU8IFzvdkIBdOm5u5tpLcz+n/tLQRArmnLQZmS+9F26AsEpTnamTx+pnIFrK3HabRYM50Bkt8qf8m0I+yqtSXwK1+W9CmYoolM1V70uSuwEsthc4R6KV82dLe/72CglTkQifDTiRev1wQxv/odt08LV8ubsUlrKDnCQMTgI/Yp2psjqGvVxm4aRkYKhmvOcDAr7S9WTK8HlMu4ZNdwM7MLHi0qirZYKC4GF14OYUcsDokTd0jiGPeOaUjOtgY5ckPDYTn5vE4+c0xnJewp5viGlBKGwwjDfxypl8QbnenMYc/IUV6maMDExperience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 5.9

ttN79hrkZXBj1WAoeAPEETnBTwgGlRM2OBpMgDUG+fzieekzrftHaT7dO1H1hvjyXrwPSex2VHMg0MMFtXxBzA/hJ36DQ54ShNxevOKM50SZVnU9CmB7YYM/+314V5gG6sot/sTi7CduQ3ZrtoYPaXZhI8qQ7otrgJm3lNAB7Nf+WGqqic8y7RWmqzrcICiWXz9gfuWZg8Ycx+Jnab4h+cdyyYqcn/fnKJAR+DTYP5c8fgXrBfEV0x2iBTmYLAVqfjz/EtDHWEZlX0y8XqW5a91e8KeHUm5PPbiCDmvELcGj+qja/2lTAYb9dAFFwwmLJPBLLQOzihyUItwJGL8dTr4tu4GXeDB1BgDFXD3LRkd51vP1FW2ZiRvSUsbjgff+YWm4PTtRFK0yqPuYoJpXgMv50TIfCuGI+pPQZ2Ce+6ItfQA+Question 5.10

ALh8tvfXY5N9I91tB/ntVHU4z6HoiYOXCxPwdNmRIA8xCjYnUrlzwsJhB2tXY4kPWRDRCwAcP1QLv5ugEQq8U9Ye7jfGs+/uQf1Nns0c0F75O1vWGTkHZJAiziWRSN9g/9kBqjBRUnrgDd7NxJKf2U4Zn9C1T1ereHuqU1cNLJAEjnH4Wtgi5AuY9licSGvONeXhB5FEdI8jCHl8Onq6lrT5iOnulqY8BeNjTcMkVX2LZf3m6buIqHgYEgE+SlwrNBRSVQB9pWSN8mX4GX6zH+2L/OV8cxDbvoJPsx7BnXL8zn3suvIELjqPTL5hDblyMuXyQcIXqgZ98uLSzrmYgMHw1bus/NFq3OlqOZaR8huaAcqzrQfwLXOpsrBzuqQR/0p0JryizpfpcLdIzlxxJRqpgHfcTME51VCQ3lOKoqdv9lRSi8lvOXeiY91oyLVrsa9oX0SivEvLRMlZOvstcG0nYLQ+L5oP/J0Q4ejbmKI=Question 5.11

AWcxpQ7oR2qo6MLbOeprIp/bj6sPbUgiYN7bwHLz5+GfktPkC3ficGmhm8g6hA30hgCj6qx9KjECLfugqkrB1rZ+eb/B3v7fh720JbyJ/Yp6160bbGyhW0QD4bPx1faQOdUC9iXUvLMQP4tu52NQuUK9rP3rjrFRSG57x9dfwulrjoi6rxsK4eSEFuQLI4iuWGYpdJfJ0zo2WnxhcxGvOA==Question 5.12

4. The use of condoms during sex UuyvZf3kfOxHV9FQ (does/doesn't) reduce the risk of getting HIV and wfuE7iNURTJ/Smlg (does/doesn't) fully protect against skin-to-skin STIs.

Question 5.13

BP+aMI08he/sMICIsrkCyUW23pHcNbvUuyk3SdWnTZG5nQH9ZKHahE08+DFo6r0lUYOTDz/AaXXWyoSAjrqUgzFvV6cMqhiLlWxSnnOVI8oVrPpxh4aEqgJuk3GD48gOwmeuDlEwQpcEr+hdurElHGdhlImvM7ou/c1tVHKgI5mjnjhugt0ILSDvuwboVqZCArQGlGL0GSuMDpAwbCrU7EtkLOL808hELp8G5aQBpscyMEtR7mgXR26CeJ+V328YYr4EnKMu9jmzKOwPhWhF5jtvRJc7gKzcpq/0g/9gGDtOk5hQ3chkXtZUQMM+u0XNJ8vy8Q==Question 5.14

i2EwRdv6/+rgyNVZplYod6jq3+ld36lJbYj50DVMGn6CmN6BokpO28cmeMM8oE+cYKi53M5+jIV9zP9+g62/jTYST1n88X8IT5YeWd8eqlE/Li99PcINMMFeOMN2dsCPnRcjZl33NBYszCQW4ieDuNNjcLeCKoVlSr+AVDdb3XRSiTHhNFXgjyXvfh4/bIwyPZ1BkPyA11d39sc2rP4XTZZhp4AK5gFyH8jMHDggVvL2In2AdD8+La3CwPuYx7fPrL1dpK4Nelzivc2Bj0ZB7g==Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.