246

How Do We Learn?

7-

learning the process of acquiring through experience new and relatively enduring information or behaviors.

Psychologists define learning as the process of acquiring new and relatively enduring information or behaviors. By learning, we humans are able to adapt to our environments. We learn to expect and prepare for significant events such as food or pain (classical conditioning). We typically learn to repeat acts that bring rewards and to avoid acts that bring unwanted results (operant conditioning). We learn new behaviors by observing events and by watching others, and through language, we learn things we have neither experienced nor observed (cognitive learning). But how do we learn?

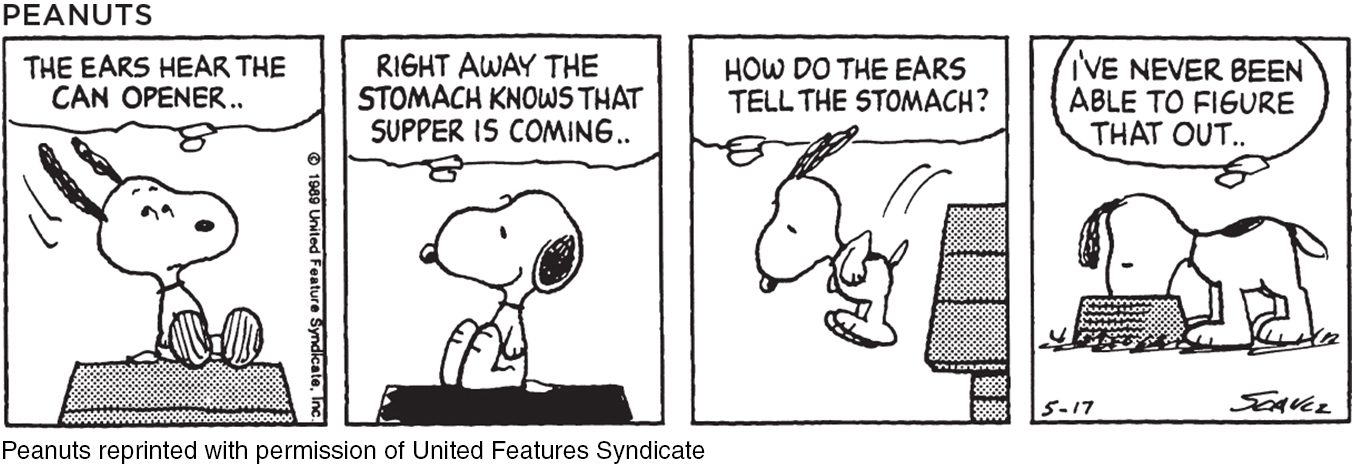

One way we learn is by association. Our mind naturally connects events that occur in sequence. Suppose you see and smell freshly baked bread, eat some, and find it satisfying. The next time you see and smell fresh bread, you will expect that eating it will again be satisfying. So, too, with sounds. If you associate a sound with a frightening consequence, hearing the sound alone may trigger your fear. As one 4-

Learned associations feed our habitual behaviors (Wood et al., 2014). As we repeat behaviors in a given context—

How long does it take to form such habits? To find out, one British research team asked 96 university students to choose some healthy behavior (such as running before dinner or eating fruit with lunch), to do it daily for 84 days, and to record whether the behavior felt automatic (something they did without thinking and would find it hard not to do). On average, behaviors became habitual after about 66 days (Lally et al., 2010). (Is there something you’d like to make a routine part of your life? Just do it every day for two months, or a bit longer for exercise, and you likely will find yourself with a new habit.)

Other animals also learn by association. Disturbed by a squirt of water, the sea slug Aplysia protectively withdraws its gill. If the squirts continue, as happens naturally in choppy water, the withdrawal response diminishes. But if the sea slug repeatedly receives an electric shock just after being squirted, its response to the squirt instead grows stronger. The animal has associated the squirt with the impending shock.

Most of us would be unable to name the order of the songs on our favorite album or playlist. Yet, hearing the end of one piece cues (by association) an anticipation of the next. Likewise, when singing your national anthem, you associate the end of each line with the beginning of the next. (Pick a line out of the middle and notice how much harder it is to recall the previous line.)

Complex animals can learn to associate their own behavior with its outcomes. An aquarium seal will repeat behaviors, such as slapping and barking, that prompt people to toss it a herring.

associative learning learning that certain events occur together. The events may be two stimuli (as in classical conditioning) or a response and its consequences (as in operant conditioning).

By linking two events that occur close together, both animals are exhibiting associative learning. The sea slug associates the squirt with an impending shock; the seal associates slapping and barking with a herring treat. Each animal has learned something important to its survival: anticipating the immediate future.

This process of learning associations is conditioning. It takes two main forms:

stimulus any event or situation that evokes a response.

respondent behavior behavior that occurs as an automatic response to some stimulus.

operant behavior behavior that operates on the environment, producing consequences.

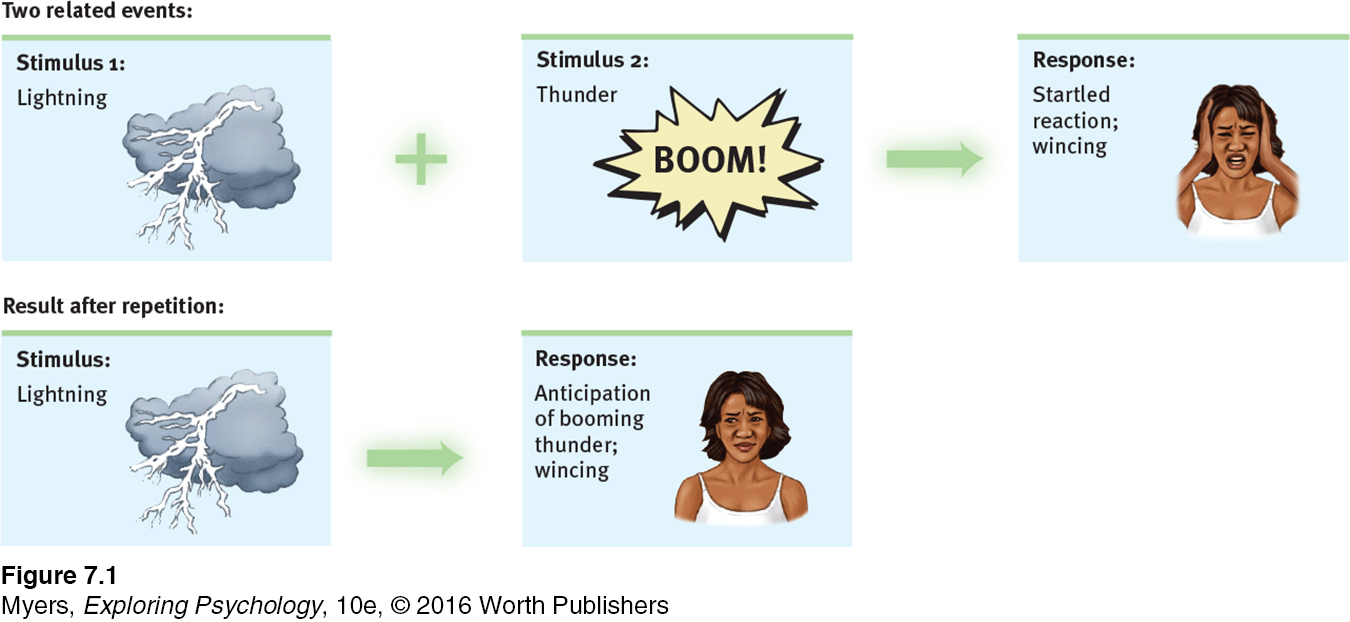

In classical conditioning, we learn to associate two stimuli and thus to anticipate events. (A stimulus is any event or situation that evokes a response.) We learn that a flash of lightning signals an impending crack of thunder; when lightning flashes nearby, we start to brace ourselves (FIGURE 7.1). We associate stimuli that we do not control, and we automatically respond (exhibiting respondent behavior).

Figure 7.1: FIGURE 7.1 Classical conditioning

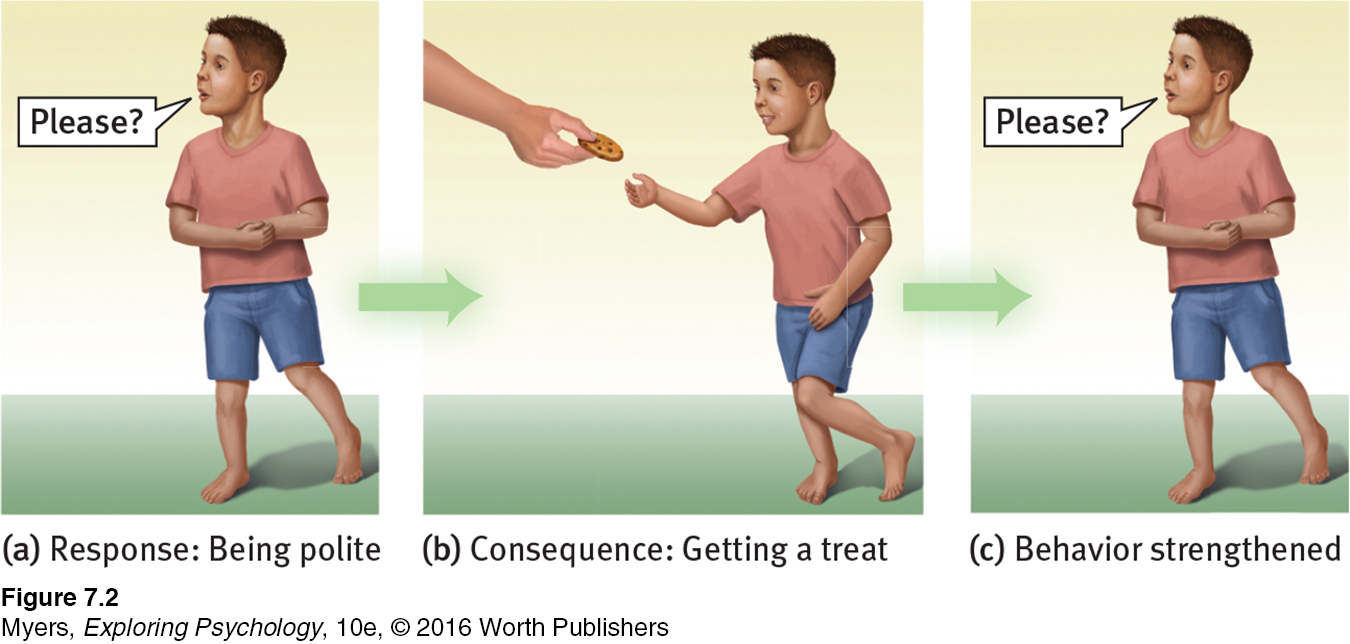

Figure 7.1: FIGURE 7.1 Classical conditioningIn operant conditioning, we learn to associate a response (our behavior) and its consequence. Thus we (and other animals) learn to repeat acts followed by good results (FIGURE 7.2) and avoid acts followed by bad results. These associations produce operant behaviors.

Figure 7.2: FIGURE 7.2 Operant conditioning

Figure 7.2: FIGURE 7.2 Operant conditioning

247

To simplify, we will explore these two types of associative learning separately. Often, though, they occur together, as on one Japanese cattle ranch, where the clever rancher outfits his herd with electronic pagers, which he calls from his cell phone. After a week of training, the animals learn to associate two stimuli—

cognitive learning the acquisition of mental information, whether by observing events, by watching others, or through language.

Conditioning is not the only form of learning. Through cognitive learning we acquire mental information that guides our behavior. Observational learning, one form of cognitive learning, lets us learn from others’ experiences. Chimpanzees, for example, sometimes learn behaviors merely by watching others perform them. If one animal sees another solve a puzzle and gain a food reward, the observer may perform the trick more quickly. So, too, in humans: We look and we learn.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

8kILPOvmDP3txYbg2i9aaaFDvPDiE8FeV0Ouwt+fRoHaRbtRx9vfdrTyPcYyOdDl27gC2eaeyqSESp1fdb8zG6RO0hC4PNr5LhoIV557f0NlsERoRhES7DplXnpGDE/M3w6hJ2F+VHcbNPvano/S6duIuR7iBOkQGx+Fqw2F8ce6jSBhdKg0QQ==Classical Conditioning

248

7-

classical conditioning a type of learning in which one learns to link two or more stimuli and anticipate events.

For many people, the name Ivan Pavlov (1849–

Pavlov’s work laid the foundation for many of psychologist John B. Watson’s ideas. In searching for laws underlying learning, Watson (1913) urged his colleagues to discard reference to inner thoughts, feelings, and motives. The science of psychology should instead study how organisms respond to stimuli in their environments, said Watson: “Its theoretical goal is the prediction and control of behavior. Introspection forms no essential part of its methods.” Simply said, psychology should be an objective science based on observable behavior.

behaviorism the view that psychology (1) should be an objective science that (2) studies behavior without reference to mental processes. Most research psychologists today agree with (1) but not with (2).

This view, which Watson called behaviorism, influenced North American psychology during the first half of the twentieth century. Pavlov and Watson shared both a disdain for “mentalistic” concepts (such as consciousness) and a belief that the basic laws of learning were the same for all animals—

Pavlov’s Experiments

7-

Pavlov was driven by a lifelong passion for research. After setting aside his initial plan to follow his father into the Russian Orthodox priesthood, Pavlov received a medical degree at age 33 and spent the next two decades studying the digestive system. This work earned him, in 1904, Russia’s first Nobel Prize. But his novel experiments on learning, which consumed the last three decades of his life, earned this feisty scientist his place in history.

Pavlov’s new direction came when his creative mind seized on an incidental observation: Without fail, putting food in a dog’s mouth caused the animal to salivate. Moreover, the dog began salivating not only at the taste of the food, but also at the mere sight of the food, or the food dish, or the person delivering the food, or even at the sound of that person’s approaching footsteps. At first, Pavlov considered these “psychic secretions” an annoyance—

neutral stimulus (NS) in classical conditioning, a stimulus that elicits no response before conditioning.

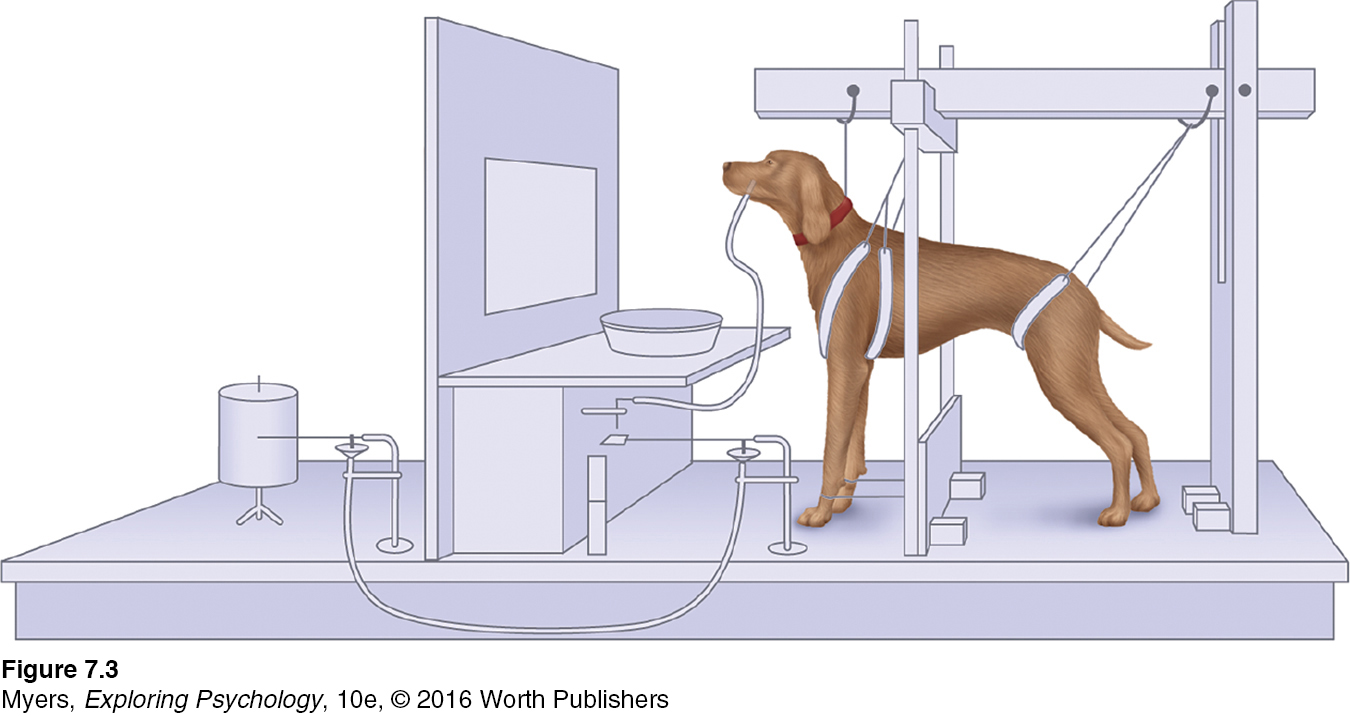

Pavlov and his assistants tried to imagine what the dog was thinking and feeling as it drooled in anticipation of the food. This only led them into fruitless debates. So, to explore the phenomenon more objectively, they experimented. To eliminate other possible influences, they isolated the dog in a small room, secured it in a harness, and attached a device to divert its saliva to a measuring instrument (FIGURE 7.3). From the next room, they presented food—

249

The answers proved to be Yes and Yes. Just before placing food in the dog’s mouth to produce salivation, Pavlov sounded a tone. After several pairings of tone and food, the dog, now anticipating the meat powder, began salivating to the tone alone. In later experiments, a buzzer1, a light, a touch on the leg, even the sight of a circle set off the drooling. (This procedure works with people, too. When hungry young Londoners viewed abstract figures before smelling peanut butter or vanilla, their brain soon responded in anticipation to the abstract images alone [Gottfried et al., 2003].)

unconditioned response (UR) in classical conditioning, an unlearned, naturally occurring response (such as salivation) to an unconditioned stimulus (US) (such as food in the mouth).

unconditioned stimulus (US) in classical conditioning, a stimulus that unconditionally—

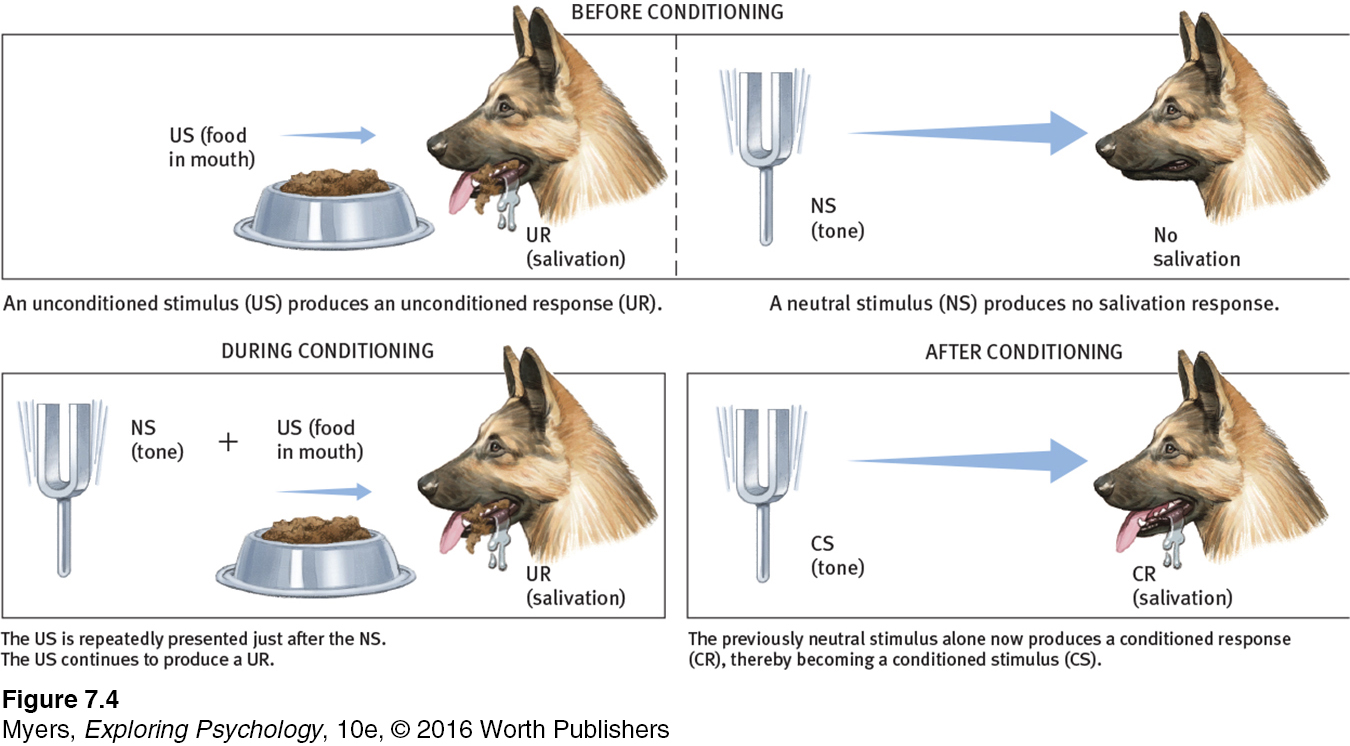

A dog does not learn to salivate in response to food in its mouth. Rather, food in the mouth automatically, unconditionally, triggers a dog’s salivary reflex (FIGURE 7.4). Thus, Pavlov called the drooling an unconditioned response (UR). And he called the food an unconditioned stimulus (US).

conditioned response (CR) in classical conditioning, a learned response to a previously neutral (but now conditioned) stimulus (CS).

conditioned stimulus (CS) in classical conditioning, an originally irrelevant stimulus that, after association with an unconditioned stimulus (US), comes to trigger a conditioned response (CR).

Salivation in response to the tone, however, is learned. It is conditional upon the dog’s associating the tone with the food. Thus, we call this response the conditioned response (CR). The stimulus that used to be neutral (in this case, a previously meaningless tone that now triggers salivation) is the conditioned stimulus (CS). Distinguishing these two kinds of stimuli and responses is easy: Conditioned = learned; unconditioned = unlearned.

250

If Pavlov’s demonstration of associative learning was so simple, what did he do for the next three decades? What discoveries did his research factory publish in his 532 papers on salivary conditioning (Windholz, 1997)? He and his associates explored five major conditioning processes: acquisition, extinction, spontaneous recovery, generalization, and discrimination.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

VKcCJ0N6SBOY+pY0fXWG84PZsvZBz6r0zymP4f6/sU4WRX0n7yebVuNdU+PgxcUsM4UYylEq4qkO96ZMy1fxL3sXnUT/VosfeJuRYgtp09I6TbNf6BAzVtpWKD0HO7UBb5VL5+TeWkbXcbXv9vl2qiZRH5LSWt2PIv+kJBXn3aSqoVVLaZYXuGdVc8BZ4U2VxH7uoojGReJgNmdMyYMd5pUWe81x82tRmpxDG0wpd8oM/hkvlXg2TK6+drlEa0dmA/jLkC9Sf1zAacv5WSXkW/iOGIXrI4L/PiPTs64Jetv+iXu6xGfdhNTQcJA=ACQUISITION

7-

acquisition in classical conditioning, the initial stage, when one links a neutral stimulus and an unconditioned stimulus so that the neutral stimulus begins triggering the conditioned response. In operant conditioning, the strengthening of a reinforced response.

Acquisition is the initial learning of an association. Pavlov and his associates wondered: How much time should elapse between presenting the NS (the tone, the light, the touch) and the US (the food)? In most cases, not much—

What do you suppose would happen if the food (US) appeared before the tone (NS) rather than after? Would conditioning occur? Not likely. With but a few exceptions, conditioning doesn’t happen when the NS follows the US. Remember, classical conditioning is biologically adaptive because it helps humans and other animals prepare for good or bad events. To Pavlov’s dogs, the originally neutral tone became a CS after signaling an important biological event—

More recent research on male Japanese quail shows how a CS can signal another important biological event (Domjan, 1992, 1994, 2005). Just before presenting a sexually approachable female quail, the researchers turned on a red light. Over time, as the red light continued to herald the female’s arrival, the light caused the male quail to become excited. They developed a preference for their cage’s red light district, and when a female appeared, they mated with her more quickly and released more semen and sperm (Matthews et al., 2007). This capacity for classical conditioning gives the quail a reproductive edge.

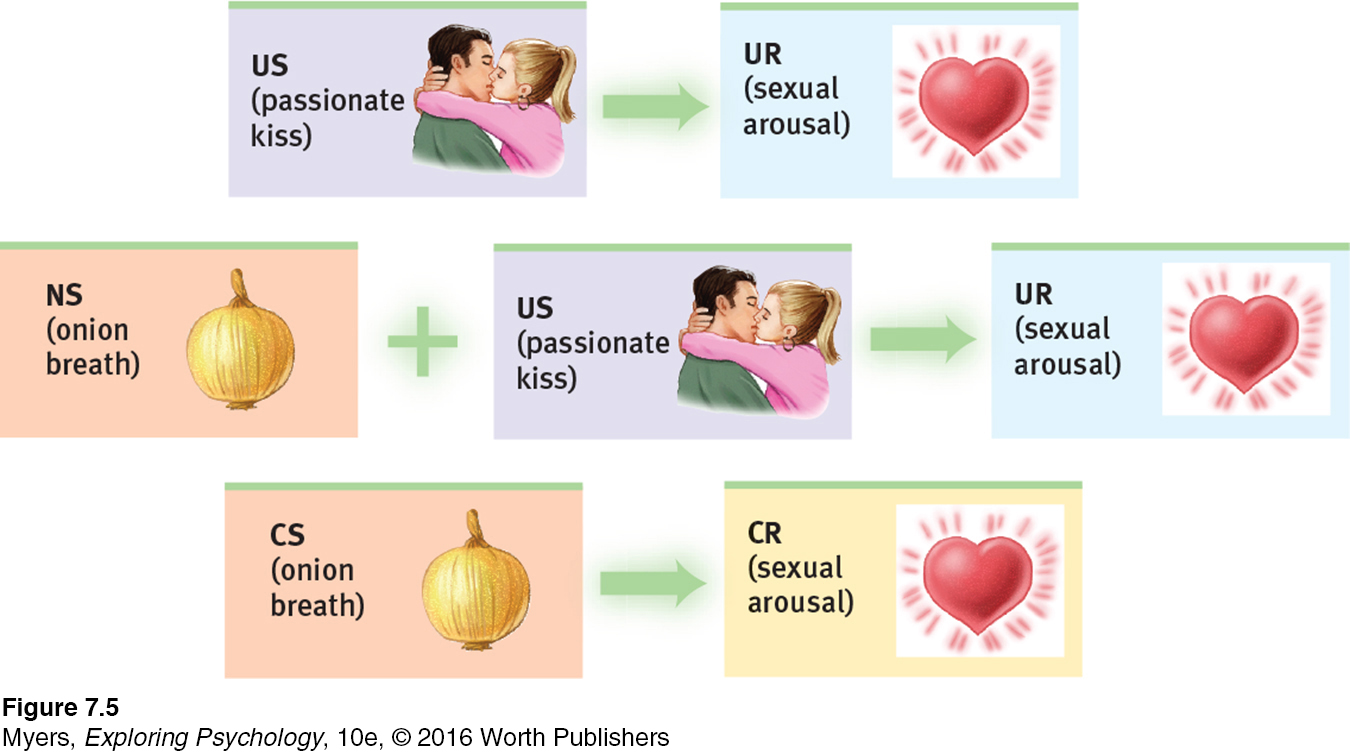

In humans, too, objects, smells, and sights associated with sexual pleasure—

Remember:

NS = Neutral Stimulus

US = Unconditioned Stimulus

UR = Unconditioned Response

CS = Conditioned Stimulus

CR = Conditioned Response

extinction the diminishing of a conditioned response; occurs in classical conditioning when an unconditioned stimulus (US) does not follow a conditioned stimulus (CS); occurs in operant conditioning when a response is no longer reinforced.

spontaneous recovery the reappearance, after a pause, of an extinguished conditioned response.

251

RETRIEVE IT

Question

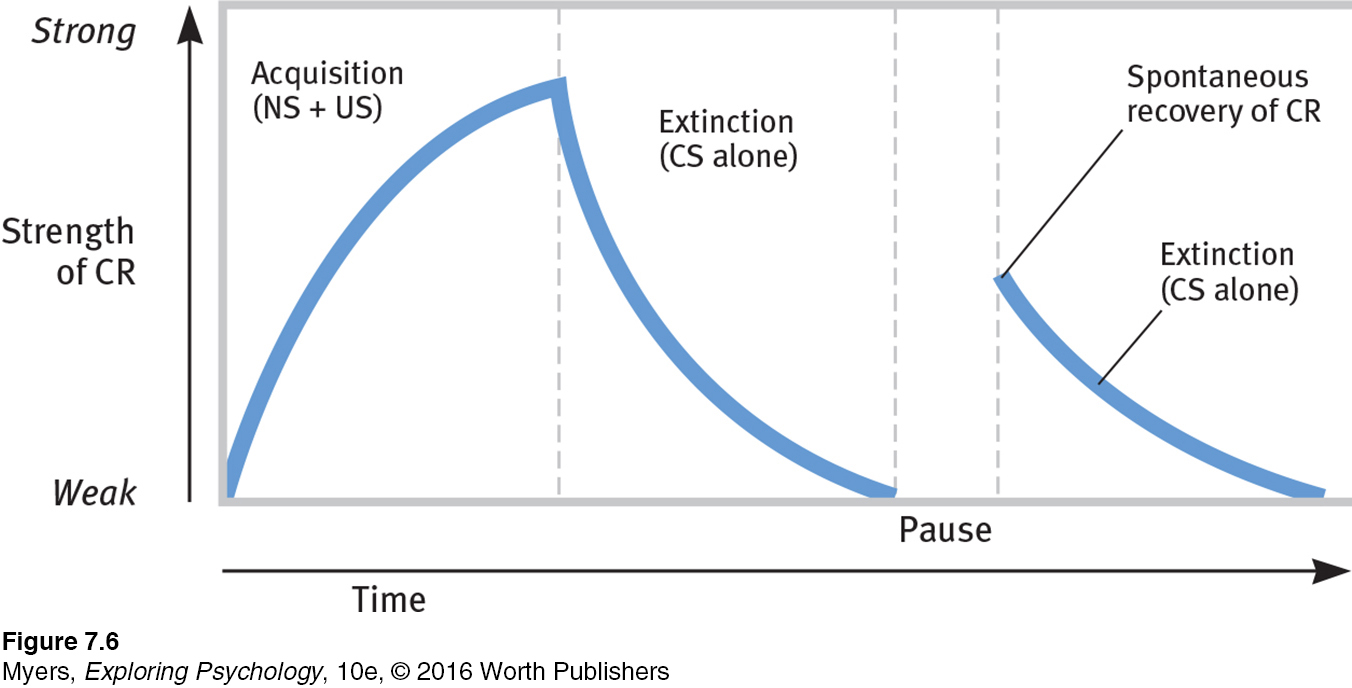

T0oziMykzZRBRH1Ke1UB8RBvNhPHO5qsts58uG4YeYRryjs20goK1yxPX+nCzpqRZAhQUczb4veMVts2ZW5GB3xCu9HBG6VskCR7/CIscebix0r+gdBGKUEOpW+6qfi8OG93IXP+COwi+iensR9eoT6zKVrJ2P2ZalVt30GLRo4CwwLBv2M2Tg==EXTINCTION AND SPONTANEOUS RECOVERY What would happen, Pavlov wondered, if after conditioning, the CS occurred repeatedly without the US? If the tone sounded again and again, but no food appeared, would the tone still trigger salivation? The answer was mixed. The dogs salivated less and less, a reaction known as extinction, which is the diminished responding that occurs when the CS (tone) no longer signals an impending US (food). But a different picture emerged when Pavlov allowed several hours to elapse before sounding the tone again. After the delay, the dogs would again begin salivating to the tone (FIGURE 7.6). This spontaneous recovery—the reappearance of a (weakened) CR after a pause—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

The first step of classical conditioning, when an NS becomes a CS, is called VY5vGSiR02twjC96vrj1Xg== . When a US no longer follows the CS, and the CR becomes weakened, this is called 8unEcngbGFfkAmMDTXebbw== .

generalization the tendency, once a response has been conditioned, for stimuli similar to the conditioned stimulus to elicit similar responses.

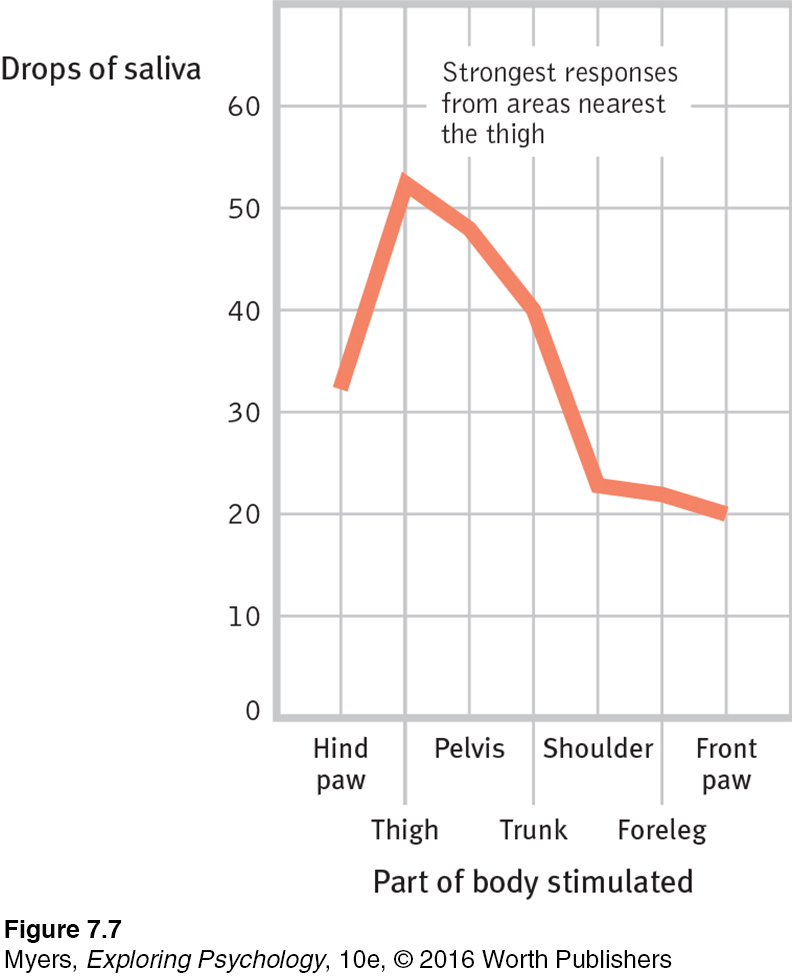

GENERALIZATION Pavlov and his students noticed that a dog conditioned to the sound of one tone also responded somewhat to the sound of a new and different tone. Likewise, a dog conditioned to salivate when rubbed would also drool a bit when scratched (Windholz, 1989) or when touched on a different body part (FIGURE 7.7 below). This tendency to respond to stimuli similar to the CS is called generalization.

Generalization can be adaptive, as when toddlers taught to fear moving cars also become afraid of moving trucks and motorcycles. And generalized fears can linger. One Argentine writer who underwent torture recounted recoiling with fear years later at the sight of black shoes—

252

Stimuli similar to naturally disgusting objects will, by association, also evoke some disgust, as otherwise desirable fudge did when shaped to resemble dog feces (Rozin et al., 1986). Ditto when sewage gets recycled as utterly pure drinking water (Rozin et al., 2015). Toilet → tap = yuck. In these human examples, people’s emotional reactions to one stimulus have generalized to similar stimuli.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

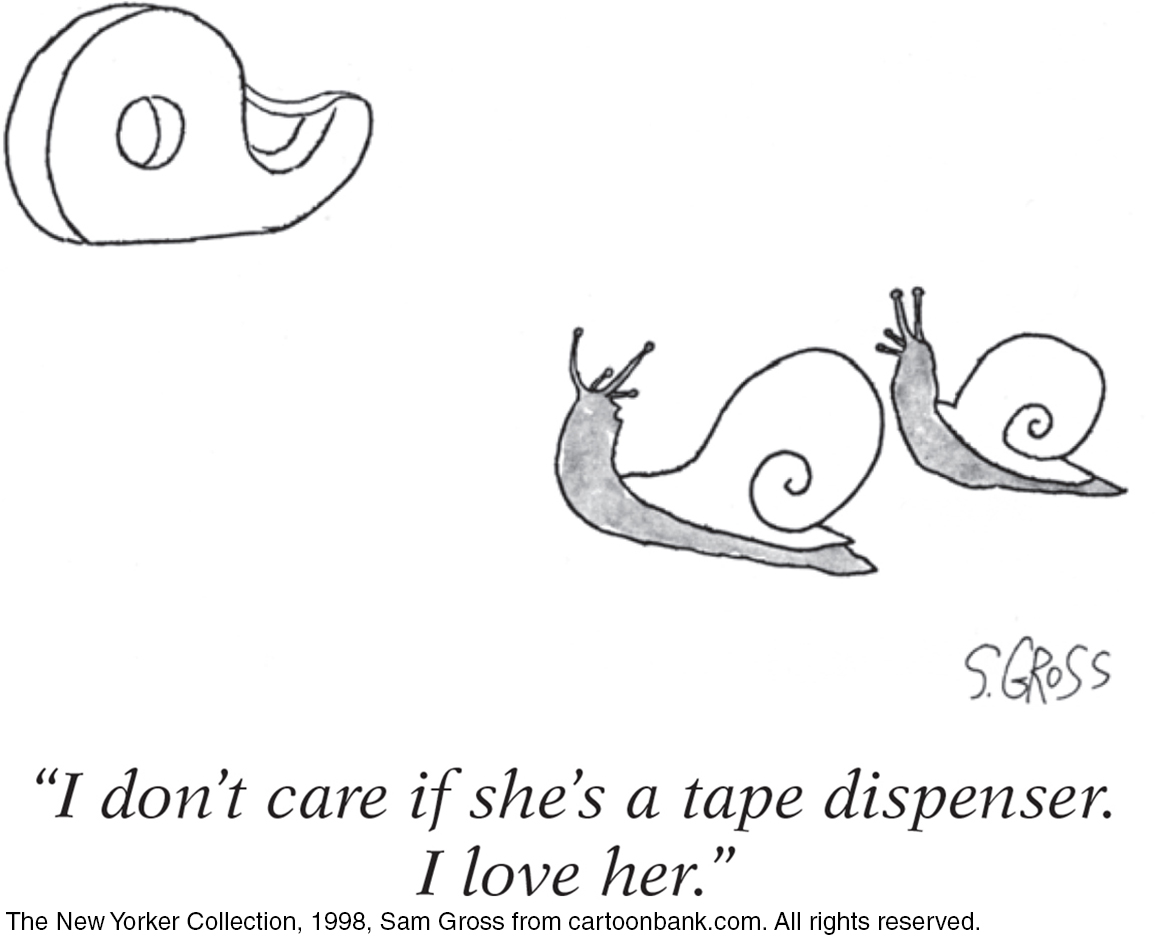

What conditioning principle is influencing the snail's affections? pgl0Yp49UitCB/A8v5o0/jWBS2g=

discrimination in classical conditioning, the learned ability to distinguish between a conditioned stimulus and stimuli that do not signal an unconditioned stimulus.

DISCRIMINATION Pavlov’s dogs also learned to respond to the sound of a particular tone and not to other tones. This learned ability to distinguish between a conditioned stimulus (which predicts the US) and other irrelevant stimuli is called discrimination. Being able to recognize differences is adaptive. Slightly different stimuli can be followed by vastly different consequences. Facing a guard dog, your heart may race; facing a guide dog, it probably will not.

Pavlov’s Legacy

7-5 Why does Pavlov’s work remain so important?

What remains today of Pavlov’s ideas? A great deal. Most psychologists now agree that classical conditioning is a basic form of learning. Judged with today’s knowledge of the interplay of our biology, psychology, and social-

To review Pavlov’s classic work and to play the role of experimenter in classical conditioning research, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Classical Conditioning. See also a 3-

To review Pavlov’s classic work and to play the role of experimenter in classical conditioning research, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Classical Conditioning. See also a 3-

253

Why does Pavlov’s work remain so important? If he had merely taught us that old dogs can learn new tricks, his experiments would long ago have been forgotten. Why should we care that dogs can be conditioned to salivate at the sound of a tone? The importance lies first in this finding: Many other responses to many other stimuli can be classically conditioned in many other organisms—in fact, in every species tested, from earthworms to fish to dogs to monkeys to people (Schwartz, 1984). Thus, classical conditioning is one way that virtually all organisms learn to adapt to their environment.

Second, Pavlov showed us how a process such as learning can be studied objectively. He was proud that his methods involved virtually no subjective judgments or guesses about what went on in a dog’s mind. The salivary response is a behavior measurable in cubic centimeters of saliva. Pavlov’s success therefore suggested a scientific model for how the young discipline of psychology might proceed—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

h6xRgKvd19m8GfU5doyR/gQYC3DKSTo+ON3gKw71vr10K9lynlOWACi6NJLhnEHHE1CTMCw/Lg2EPDWtA1GNQA86gu8r79MO3lF/1cY55Ve9ThAtpZcWvCSYhFqjsj+vzH7fTkaZajK0cYdqVxKjG3IOl39ONqwrqyW070Ps96IRTHyXNwz4LHxeJkGV5YArh671BoqhUC+66eSzBsoenoWa2nvJnqCS6L/IL0mpN+wBrePfBFwJYryslR8m9pFU0u67r2+5EHxBqf+Tyny2f17L2Z3bYLG5IFIHkARscNWs1D0ekfSeWrX3+iI=APPLICATIONS OF CLASSICAL CONDITIONING

7-

Other chapters in this text—

Former drug users often feel a craving when they are again in the drug-

using context— with people or in places they associate with previous highs. Thus, drug counselors advise their clients to steer clear of people and settings that may trigger these cravings (Siegel, 2005). Classical conditioning even works on the body’s disease-

fighting immune system. When a particular taste accompanies a drug that influences immune responses, the taste by itself may come to produce an immune response (Ader & Cohen, 1985).

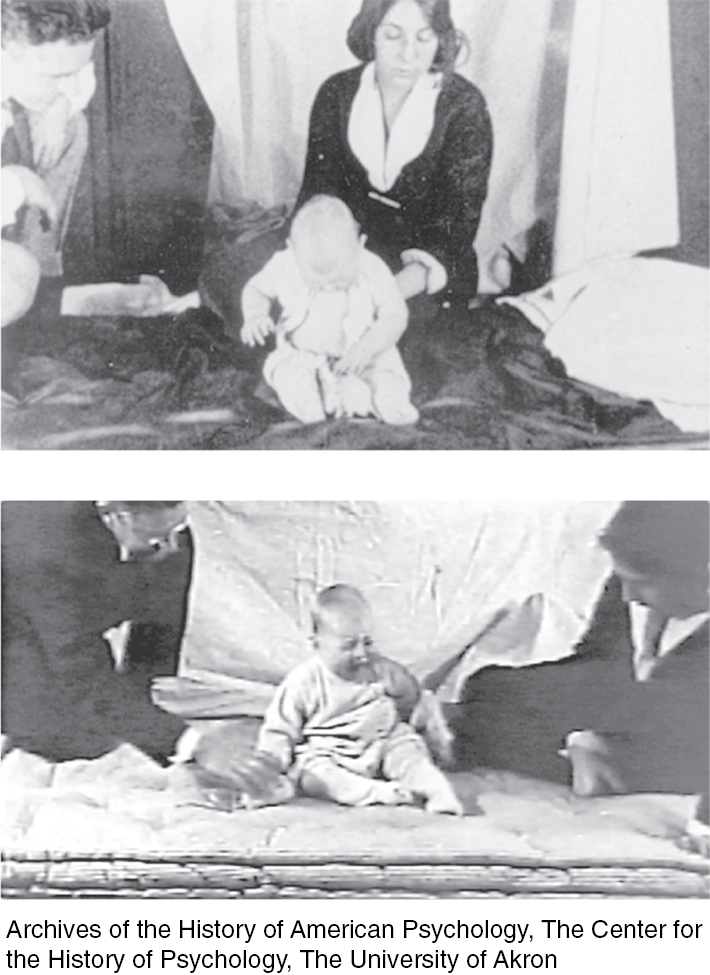

Pavlov’s work also provided a basis for Watson’s (1913) idea that human emotions and behaviors, though biologically influenced, are mainly a bundle of conditioned responses. Working with an 11-

For years, people wondered what became of Little Albert. Sleuthing by Russell Powell and his colleagues (2014) found a well-

254

People also wondered what became of Watson. After losing his Johns Hopkins professorship over an affair with Rayner (whom he later married), he joined an advertising agency as the company’s resident psychologist. There, he used his knowledge of associative learning to conceive many successful advertising campaigns, including one for Maxwell House that helped make the “coffee break” an American custom (Hunt, 1993).

See LaunchPad's Video: Research Ethics for a helpful tutorial animation.

See LaunchPad's Video: Research Ethics for a helpful tutorial animation.

The treatment of Little Albert would be unacceptable by today’s ethical standards. Also, some psychologists had difficulty repeating Watson and Rayner’s findings with other children. Nevertheless, Little Albert’s learned fears led many psychologists to wonder whether each of us might be a walking warehouse of conditioned emotions. If so, might extinction procedures or even new conditioning help us change our unwanted responses to emotion-

One patient, who for 30 years had feared entering an elevator alone, did just that. Following his therapist’s advice, he forced himself to enter 20 elevators a day. Within 10 days, his fear had nearly vanished (Ellis & Becker, 1982). In Chapters 14 and 15, we will see more examples of how psychologists use behavioral techniques to treat emotional disorders and promote personal growth.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Sbgcgf+ttj37n65GEauDH0gKXJPuRSChyttVqJRYfxMfXOTK34RiHKCCrp7RgnYeNBk0CsiygoSyyiBnUG8UkTCF9vJQG51AnHytu6EIDAQNGSyvFftHp23a6sN3MX8TuGS2Eo3jd6KwVpShfZceTrWhz53QaWA26k2uKBCw0/Ke/T4/QXORnpBOvzntC4YgES3ir+YsP1/eQnvWTqpCUaER2cbfaDj+BOcbBn2VcNnLUAIJjIWjM5wohm4tESe7OvlDvkVtLPWKg0AL2BM2B5e/3HJxFuykbCGeT0KpvssOXkbhG/80J6L+a86P1ikFat5NK6yi8BILLufWVTacxAOt4dHR1wfCF44udLAxZ98=

Learning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

255

Question

iU2+MT+u2y+AAPoIUu3LbsGkeNopqj98UBp03XlxygtzeHn+NHlF/4X81IDGHxJ7Ub1I7Jbsv/b+Bryb0QEzUL+OapxnJkPAaMI2Z1d9pekQkuZUFhvrf3fnWT2jb5VTNLug5n344IFPwHvF+DU1dSl3l4b54ruXXHnkHVTBqu0alJE2QdkZfcaTMtEXgT+Ty8N2Nfp/Wvpn1BF2IvH4q8xT6rx+kHJib8Il8s7Z6IFK01aHo3uQFA==Question

YAR5CXl/V5R+aTvXEj2Yq4RGbqS+6lBXqqNx/idAvpaz8k0DieY+rS0vbKnngXzoe4N5MgmVOu0IxcE84SJ7tdIt/ZyZSzGl9G31w9bnPHY7vt62IN1GKKbNdsDxoSrIV7AO1LQTjXh88yT6w7f1IGJbumqzxV25FvO1LbfiFeB0O8+l5MV1nTq9cTtD0LmDDYBabWqXQLSCpGcUQuestion

vCxexB2EZy+SZNdLwvpRFLyQ+X10i/sySew2x0smhxwMpcwLosQ8fgcbeJ7CEDdXz2V8OaJ0vZi8h0kfUTd9+s6CBX/ZJbK+Q445lnLVwWZO0rxdgBpDfEj+I2KB9ghfFo7afOStYSbZZd/VMgJTi8m6xpG80IlYo8TOxmE4NbTvm5UxEIAu+6XDJrbgGB3h+MDADiJ45eITof9ctANPImExQzip2m3q9iZSaHpBgnpWojDQXVqhUzNtSVt8iEKSQuestion

h4Jf5IVyXSo1WEmOLPbNcFShLbIGVOuf+/kq5mYwJYgVRKxmfF/K3Z+AfGqvAz3lc6DGE3x/nqqWPtRQj/6940OVcSrG8fNZhVW9W8CPSP0VKRWidwToH3g68VqI+ypvbs3OoiKztxzP82LEcyZoGqliskfUWrqm6Fb5U6J3swQH4fkyeqr6kuCbtDty4m2y8M/DsfB2LqG8aF/Bk9fBXYwVuevYctqDQ0csQaKkV1NsoE5xEAKmvBoNckfiMUatmoYz621kvMDbeSjx2lQcPavdCl76mAr4NwTxQ1v8rT7e24T+lh7QiRwAsLqzVMQQHog/TU6FE0OLAULiQuestion

Aa+miFNzSc8gKuJDkFL01EuPtu07ERQSgv3J4a3SdI0rg4rxSK0KQg84N7Is0WveDRKCDmcXx3ZyLvoMsTxdfrcCr6YAuWivza2IwfyyNjsxxF68hr3zVD2+dP/ehVpFN9hbQAHjnZGCfkejZjVtOKdZ3QcnZh4W+urFh3iI7K9/bL4ipAFT+j5N4BOLHWCmNA5DdZgmqRjXwpueHj6wYg==Question

GOVyfl3aBUJq15CdUM+qBc+TUocFlR8VT6k7kw9MD9Dgj+tHNc1zgY8sBPNX8r3te4V+8Cqu0SzhmYgK92hPZJRcVbN/XwxpS9nLPSyDuL1sHDyLTkjB7MBBe6/dX3MZNl7CKJC4MlNEO29jGo1osmyVFUvDTooj3tO0TuZf8GfC3hT0TsAoga4xx4CEtXkyCpFNbMP63Asv6b0UiZCWux2dSLOIAvI5ox0vrFMaAS3FVI7GwScT1D71cqAhukenjsna5DZ160uRbiwZsfCL35LSPuE6K4vg4Qp5RdjXqNgWj1I1q/4kWsglo/MpaEkZAH4AllC0xQUuscH+R2DzWGoeljhGUa6Cdlbp9D8MhC5k5BpEfgu8N7cyF8pRk/bakSZh+NAPLOo2oiwJJfwz/Q==Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

JcFWVQxRiEq0TlM4q9H+z3Tk2s95C6tCwrzwSZ39RDaVSFDjRc+7sOkJK0cahF5zLNsBDDhTzVpevOPHD+8pVTccLAsb9R29nylZZ0YsIVHLFWaptmFrE4wNQqbOEmsLmUE6uFFKtLp2qFheL+mJu0AFA5Vp0kqq2JkGbBCLhj3J4mN3onvRssVNdpIvNRnvmYOqjOLDr9aEqPSgQXw8ahi2a5Rb4riaCBqPo1mlBP12Uw3ovqzL4wouveOahPtC/pKRzkkfJB6Ix8a1ax5VhscQXgiJVqyLNMz4awQbCpgZ1m7GpeJTKCK+aP1sTmUxbD0XCxXqldaCqI2m3tYv5B36dF4YxAgcog4kWOuNUp4wCttwmkADfk+xi5FrSbU5uqOcooCqAPq18zIRTU/PeXC8eHgvYHHl/rqvz/EFJ27QYOsCkdO7IfVDEQy3TUsXMbxXHR5991GF0nKpGs+Vl2eCvyDLH2ozUzN0VKOlqaSUsC7auyhGOGGDR0AToeAtvSC9zF99RzRm68v4MKPvaAsm5p+WlpIjZr7zPSzyJUMXw/YCZXb8y8MWevAUOlDwbPcpsvJcMtdkpWaEc0/zXRUurc4ZrDrZTMF1nHK+Rg7CoAIRANIPyVjaumsCpqI1fnpQeipzgBEVbt5yPHztMMCfccHPxj3pKX4gGQQBW8K+nKSCDboWLMvcYRNdh8tcd3GOA+9O+pq4HHhIezINBr2m7qhDvKItWzJy+mLsolhxrA6i3xryJPmbIiK2p0wyMfslFmD062FSIHMDTC6EqpZzPwcxtbXAn3nVed9+M24yggtVkSJkA69Btd3Wn2tdvNoj5tRzAbXuHpdqDuxf+Bh6sh3S6QsbBBfiletgmlfDOWYPIA4Jm/urGhaBPWQcY0D0yjf9fMBWMcRijlgcdHnCmbVezR2dDpdSDNaEQAsIHA3UmSY3DZYeS8tDSm6a/+QffLlomFAvfZAkGuwiq/f+bo7OMW+U1zjG2GgMGgvU2Bgnc4MC/PHRcAir/RMJLCb7oAS0OpcorMFsJlgjAXl8b7PiuSd5e53R/tky/StjT75WM22x8mJ8iXwt46UG7R7rUGVhTzRFX4Rq+SIfc3CEUx+z4IFjX+9lILnN6XVeX46Y+353mlcl2XX6QgwoirLU/9WheGYIaxCiyau0MLVlKciewUmEXmwmDJPazsA+3ptuiY5sKOBlQypFG4XJ3KUHZH31VAN229WbZeSRK67AGMfmqJxEqhXvbfJBBGo2UB5xwflh1r6ihU0kGhi41FAgUyVSqpI1AokpHOy0WIuH/Vgf0vHmI0vuW81HYXxOWZ/cOpzx+V+RUikWJSsNCQ6E5erVByRHkR6CseoB2YgwQtoofKo7IGyQX6he2uii1EyJ691zdK6uBi4byRONCmCmQKwRBVUSsisJxgjHTt2IZ8RLsDwYO5Ip2I9pn9SN97KERoTYWrXb03gq/HYcoVHCSiFCCfYzS7p9i9FomN2NzBi5DZxopOqXnm6zfF/RrJl58/Mc3Og0MG2VRHGIyKZ9rwvFgOUr0PeYMWSWpd3FcRYbo2gFc6vdH9iQMCTwsbvJI7lFN9OfFGGzrFI9GSyzFRXUO8huGTX9JCFLAZAfew4uOi0ZPOjYKA3K+1pvQ2+qeo2Ag2gr7oeu+07r6XMmqn1jElm6EhOHWz+fUjx3UEASo8DfW6JE5mjxPaa6ipPeyDnmDz9OBg9JvZeeDo1smM140FGdQ3snrrPfGw7iipEBp9osrGsiCFzF3j/iv0jiGGaDevLCEz6DnylKGfjFLIA+JffsbbBdl1xTesvZ6aC6EEdVs9Q9oAgU0teOVifs0N6isDYUCm4+hLZfEg4tUzJVJ3240/8VyCn/L5D1JA+nR5GeacQIzq2/wHDefdiVDYvDxyHGFBRAhrXzlXd41DRvwF/YZBc0TtRjREWWnGUcTrgP8BGLDkPG+C+ZoqATaJlxxnb+PkzG/9bM65HT++PJpobM67qnYHoGg66enGIUOgRmL8qn0Dly2fhLaG9kNkaV0urC+OByp7UVTA85GbKBH+9trUVDUQq5tTt0UdLzq9ng8JT72agVCv1ddhDUojceDMGjOf6gIdNeSyUzKT9Dpde3TcOlsm8tWsxr67b8bfhWDOay9brne3w0Yikm0qlWSOTP0Fr5zMvWDoV7xgrAlGoWJL5QbvfbhF5rXgpFMYk5cHxysZsE9HP/sLLwXFsV8EwYMZ4/vDbVpQTRbioUMQ42F0LJabCjH2LvBjy4zK9u+FifrZ7sxY6NGKRySeXuUHGdpF5wEjOlSONxdHQx79vlqCtmtzsyu1D120fCVS3BV34Jw+Ei2P+3tVJAeAsCYMNMT8Xz0k1VzKrw6Ibj1FPhHqNkT239VTITCyZ/SFR692MF9zTK46SNnB3ZieKAVGrtwTxVmqQPnY97i4BC82F44qFOZ/PlG/9IogAPfVYzmanqLAq2zHkmeqolUv3MR3MSoa5dbqL3+1rqxALXd9zzDbSDhsRaK6zMahUZXaN2DGl5JHlykqBtK9/gW6fa4kR66/JqKFJCRW9I3cGGKmeWTkfIFWBN3hT7DTDjirtNwNUzavMiQeRsKk/9Y1gIZ1QgyohhOf4fuGKtKe7ope92/i/mkhqM5YDYY6ueOL1nQPhOlkFgM4z45+dz8aUtURlAmujSwEune/2IgYVelQx8JrA8rumMHt+Yuc2WVEm2UCY6qdNepeCPVr1Dvj+bjB0QeRDjXFtC5Tlw82YR6YGFIIIcFKOgyy5zMCIh1XCAoxH+NiCgN4kTkP10euBrk/DQtMTR19cv/t9G44P8mewPXjKnDFo4kbjREXnP+sEsyQSqG6pho1JrMMPWUDtXuhsgErbmVoJ4SJ3Fwksv+thkVWdrQYPm+RjzRZT76ZC+eeX/ObrxfavkXRf9qmPkr/ez9tIz9KaSNmlDBC7rKO7l0lyEuKsYcyLafh1LO3MVe2ZEMZRiWESUYa312P584cbaEwZsr/YWCZd50Mu5Dv721H7PMu1FFLFkJxWC3kiClRxaY7a9ZZE7v6n5IZkYMbWNpfcwTCu3LN8hFBQa6MqLJ4JC2MPcGF63IyVaKJfD6c8Cs286H+sRfFxd8M8lI5DYSDTCBTlZBH4BCEjWotn44ZHrglaX6N8xu/7QUTCtrKWzN2kjkPGEJnEG9RIT8f70X2ghSOLAzExwubAfJ5vM3ug1ve6WhzYf+Gy9FhoALKOch4YfZVor22B/0dOp16FWl+DIuUd3bzLdBMAi5IakugejxgFlLeCewc9F3mDLQSM03F41MT7Rnw45Q7G1uidwCNbtpaXTU3mvaQP7xRDZv7HGXdw2+NHshwOhVQmiel0paJZsjJ1iCftHNNdBqEootQAEk3MyQxHmwQ21nBVV8QkQ/xnCd03WBpMLfKGPJq4v0JmMeSltja3QGnV9U+GEbhdEkg25Bvw9r4TUOmabx7uaoZ617AAE4OV2SdTgwvfcdGWJmPEFBzOxPY4q+Tij2sMG+PUFeuZnT1MwwFeYyMFBezWjSktMcPGMrBwuxvzu/vCQvyidBXvdNaHVuKUEp1MW8TFBxeaAjvt3NVZ/gX1ZFLgQQUu23wKjMp7pI70/nB7SjWAmsonWLK0vcB90jjkIrZaMzf6re8lHq59gv6uxA+YRPetyuu58oy+eEytVh4hSvgvQTrsotwaquo8grg6d7b4c+nOCfUD4da9UFwXpDl7+v+3+TAZbZd/vZcb5BduKhz6E3SFs+BEOcY2uJ6BPYX0x6dd3y/MdiVtWLDr3PJQnFayINaF0A1RN8U4hd4r+IfT2FjxNLc9quoQY2XU759k+Tyb4rJeXDmP4cPy16R3FLZNpkcvpu7/Fp8ehdrBJ/OAqN6t7wf4jzKfwjTmZjPDRTYGTmhA05V9EFzQtKsjF66WBY2idaCpTZEZGdOPxMpfuQp3zSXI4kcuNrn7Ot4gF8w7WKwU4Sqc=Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 7.1

1. Learning is defined as “the process of acquiring through experience new and relatively enduring uoZVGt17PaLKQIiGzHDZUg== or abkzxqFDBPhflDkgmSAStA== .”

Question 7.2

Istipe+g7fu2scxv3USxTgBRDjhPufPtWTKbgNRhWeT2hu3fwpPlnwszztILmWHFHoHNGTsA673s6yqu1Mz67YkCyV+M1wpTbGHmScCJpA44J5pq6lY1HxTkOZoMWVuUtRzlyHNGzhqi8CYaYbq5eVWLQiksfXTM3Uy4/ve054wI7Eb1hBYaegnXn3Wc8yDxqIeNwLGeT4RMZnO7XEZlzoANdvTJhitPtkkM+zqzNXPcU1Y5Xr93nta2ZHg4kfmLjkMQNcNq0jcm/jpSMxEoIJIbAwqPQtqCOhMJNziqUFRko+25KS+JLdAd4/dbJ7NTColym8OWAcI3oCerTfpCdgreEDr9O0I4BNCLmJFrkCTJps0KAJ8wy7iwRZKyysLGzKq+c1eBwtvO0gCUA6hCWv7sR9DVdRqyFpHWyNtbVVFq+tbWgU8mGNkU479WovQ8rxmpv1MXpJOuftMzsjxPoI3uaBh3lqYezVlCIQHE07hGOhWaRknKetm2rp/EUN/jVeGohQmG+hIwFqp2bznkNO9y7blNpX7sPFRZZaP2ZX8ro0lgQuestion 7.3

3. In Pavlov's experiments, the tone started as a neutral stimulus, and then became a(n) slGpC55vFCkCaknmok3ApA== stimulus.

Question 7.4

4. Dogs have been taught to salivate to a circle but not to a square. This process is an example of 8LtQ7XxseuI977wWyoVQBUoTdAQ= .

Question 7.5

6UpuXP/a7EmMwF5d5bs9/ufWPcwfdnteZlpkwclGBiA4NKbqHH9Y5nE/ta+IR6kiaxD9Q9TJfMoWt/G5e0WKFjt9BcoIq1/rR4cFFOr8pWvkB4KhW3y2ApyVz1zrJcg7xXxFHNBobKSDcEEUuZaqdpJ8U2yRngPwwcT+UmzFOYfDgtfCn5o0A7DO1nO+Kv3Awz78mppbz61L2qTJtTMLupmT5znYp8X8FyvRUNGycSHBuKMIl7PO6kRsrqVJ9e2HLT1DzLFtamgB51h5dLnEoeY+k1k8g6apSNj1TrNdXeJ0K+ESu/wso2HSli/aeLcpRgQW15rxFIeRr0EQwDum809lDS419IsQGFthdLnZ2zgAdg45Y0rQ06Ljs00LM0o5TQm2g77RE29XhLiBBUV2PNAoHzBhwoWVFwcf1bv+V4Hj39btsi+DoyNUXAo=Question 7.6

gw7+TsFX1oav4jQ0//4pwcLCt9zgDd6Va9CPbbV7FtgMXUkHurkdcrOcNibJn3xknrdJU6KzfS36/NM3+o1FpMix8mgXUNeC33AyIfk+D1XIFB+xyOkI1qE2S0mY2ayPAcEq4ehtRzNmXFdgLMM1Q7PE3DToftGRuKyZ24/pO0rZIwgGiQFnH5o6GOo1eguVAuVPS8jKF7Ca1n2pGa+2bMfUV89KVHzu/vDFjHRRZXyXlDKQeiFFcrSPVyA56eNERxNjGHDmMfHBRHsUYg5JSGU2A5o5y8P7wxBqCwp2IwG3UErdV3acMNrup8tiToL0LZIlEPOI95Hrwp+eG1J4vtm5NpITTmR8MoPzjQ==Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.