9.4 Genetic and Environmental Influences on Intelligence

354

Intelligence runs in families. But why? Are our intellectual abilities mostly inherited? Or are they molded by our environment? Few issues in psychology arouse so much passion. Let’s examine some of the evidence.

Twin and Adoption Studies

9-

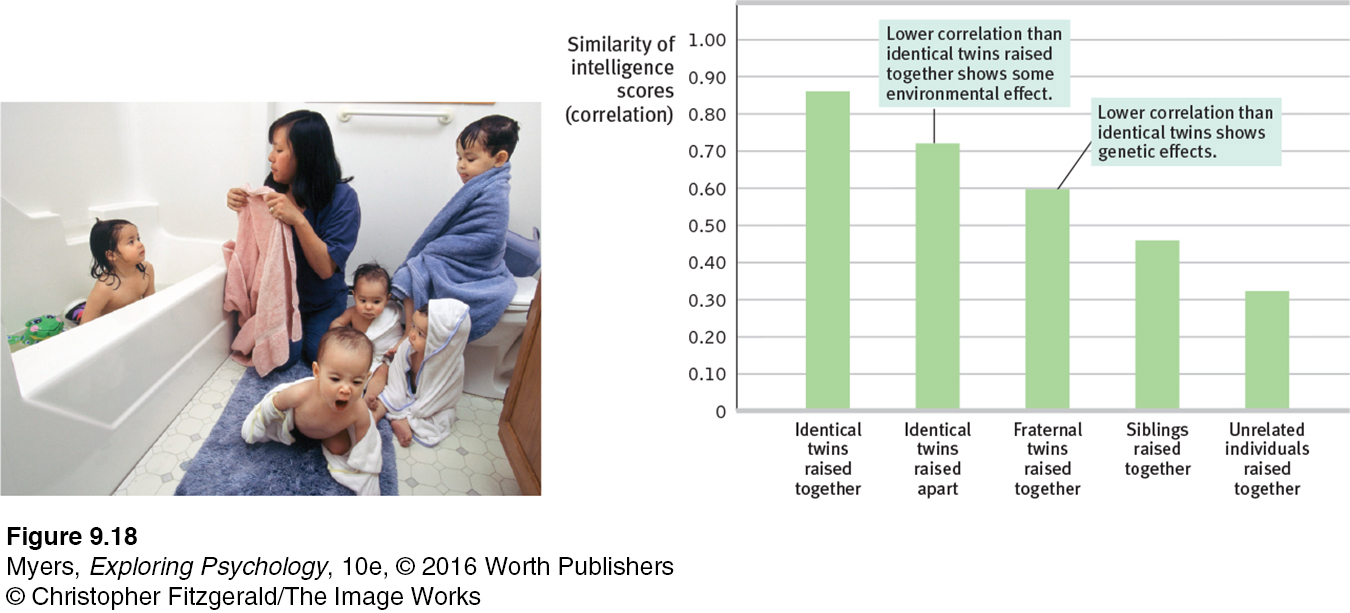

Do people who share the same genes also share mental abilities? As you can see from FIGURE 9.18, which summarizes many studies, the answer is clearly Yes.

heritability the proportion of variation among individuals that we can attribute to genes. The heritability of a trait may vary, depending on the range of populations and environments studied.

Identical twins who grow up together have intelligence test scores nearly as similar as those of the same person taking the same test twice (Haworth et al., 2009; Lykken, 1999). (Fraternal twins, who typically share only half their genes, differ more.) Even when identical twins are adopted by two different families, their scores are very similar. Estimates of the heritability of intelligence—

See LaunchPad’s Video: Twin Studies for a helpful tutorial animation.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Twin Studies for a helpful tutorial animation.

Scans of identical twins’ brains reveal that gray-

Although genes matter, there is no known “genius” gene. One worldwide team of more than 200 researchers pooled their data on the DNA and schooling of 126,559 people (Rietveld et al., 2013). No single DNA segment was more than a minuscule predictor of years of schooling. Together, all the genetic variations they examined accounted for only about 2 percent of the schooling differences. The gene sleuthing continues, but this much seems clear: Intelligence is polygenetic, involving many genes (Bouchard, 2014). Wendy Johnson (2010) likens it to height: 54 specific gene variations together have accounted for 5 percent of our individual differences in height, leaving the rest yet to be explained.

355

Where environments vary widely, as they do among children of less-

Adoption studies help us assess the influence of environment. Consider:

Adoption of mistreated or neglected children enhances their intelligence scores (van IJzendoorn & Juffer, 2005, 2006). So does adoption from poverty into middle-

class homes (Nisbett et al., 2012). In one large Swedish study, children adopted into families with higher socioeconomic status and more educated parents had IQ scores averaging 4.4 points higher than their not- adopted biological siblings (Kendler et al., 2015). The intelligence scores of “virtual twins”—same-

age, unrelated siblings adopted as infants and raised together— correlate +.28 (Segal et al., 2012). This suggests a modest influence of their shared environment.

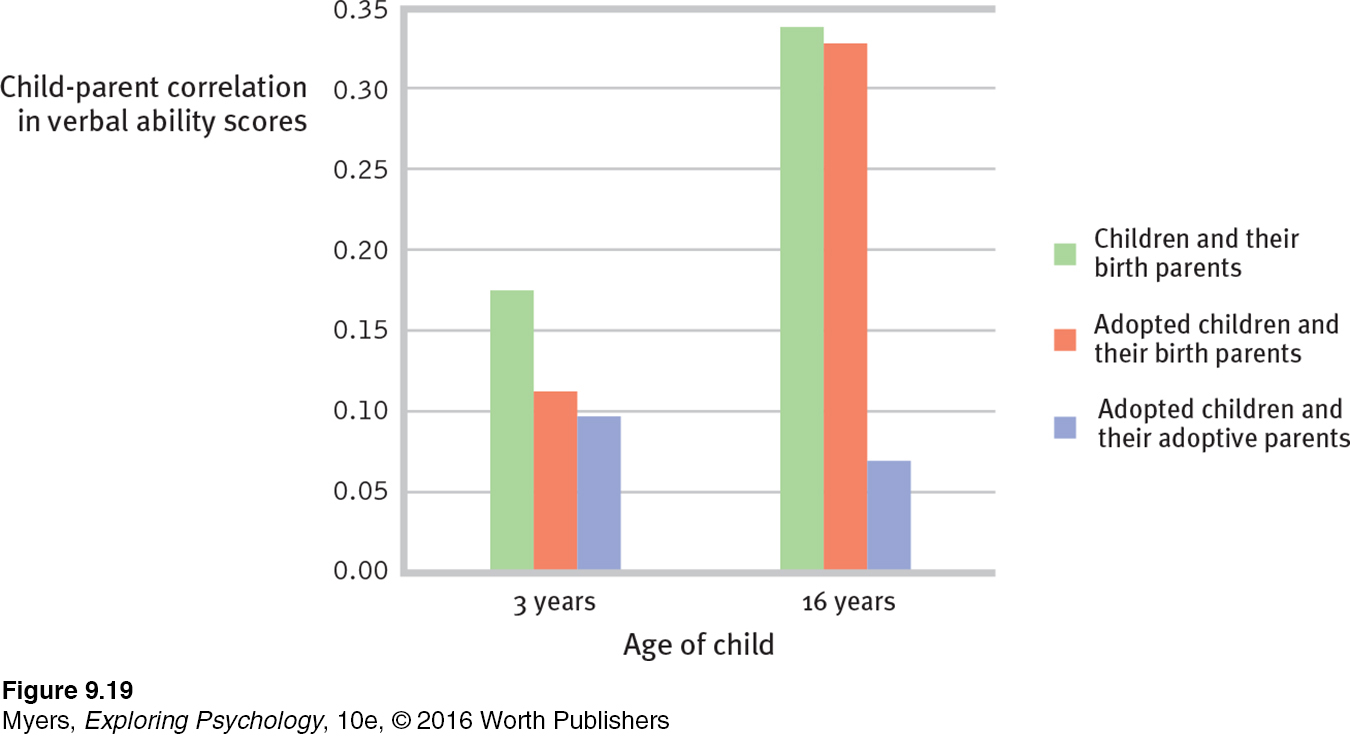

Seeking to untangle genes and environment, researchers have also compared the intelligence test scores of adopted children with those of their family members. These include (a) their biological parents (the providers of their genes) and (b) their adoptive parents (the providers of their home environment). What do you think happens as the years go by and adopted children settle in with their adoptive families? Would you expect the family-

If you said Yes, behavior geneticists have a stunning surprise for you. Mental similarities between adopted children and their adoptive families lessen with age, dropping to roughly zero by adulthood (McGue et al., 1993). Genetic influences—

356

RETRIEVE IT

Question 9.22

Eh28ftBognInQZNfOeaBof02D3O/lMIWqOfLF5bRmMP6no5fcNEXUF6EHc/0MNHJoGsDMBnmroV4pGf2YwFi681t0VYZrx+kiKBJ3MudKkK7QhUHInEL11d0nL0fI8geKhXcMWvry4UlNlK6QQiQ9BRmZdW6dthHHMWPyp1ym19PJLDYmhdshAqtcSVnH8Iox/Vy062/3iNn0i5ITOyMh/fDzvG2j8V+chTFwUTYIfiktcZ6AyOQQj2rF8qXXeFHMuWg36jDuwLwdx5VGOqVZwPqjmc=Environmental Influences

9-

We have seen that biology and experience intertwine. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the most hopeless human environments. Severe deprivation leaves footprints on the brain, as J. McVicker Hunt (1982) observed in a destitute Iranian orphanage. The typical child Hunt observed there could not sit up unassisted at age 2 or walk at age 4. The little care the infants received was not in response to their crying, cooing, or other behaviors, so the children developed little sense of personal control over their environment. They were instead becoming passive “glum lumps.” Extreme deprivation was crushing native intelligence—

Mindful of the effect of early experiences and early intervention, Hunt began a training program for Iranian caregivers, teaching them to play language-

So, extreme conditions—

More encouraging results come from intensive, post-

“A high IQ and a subway token will only get you into town.”

Psychologist Richard Nisbett (quoted by Michael Balter), 2011

A child’s later schooling also pays intelligence dividends and enhances future income (Ceci & Williams, 1997, 2009). What we accomplish depends also on our own beliefs and motivation. One analysis of 72,431 collegians found that study motivation and study skills rivaled aptitude and previous grades as predictors of academic achievement (Credé & Kuncel, 2008). Motivation can even affect intelligence test performance. Four dozen studies show that, when promised money for doing well, adolescents score higher on such tests (Duckworth et al., 2011).

“It is our choices . . . that show what we truly are, far more than our abilities.”

Professor Dumbledore to Harry Potter in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, 1999

Group Differences in Intelligence Test Scores

357

If there were no group differences in aptitude scores, psychologists could politely debate hereditary and environmental influences in their ivory towers. But there are group differences. What are they? And what shall we make of them?

Gender Similarities and Differences

9-

In science, as in everyday life, differences, not similarities, excite interest. Compared with the anatomical and physiological similarities between men and women, our intelligence differences are minor. In the 1932 study that tested Scottish 11-

Yet, most people find differences more newsworthy. Girls outpace boys in spelling, verbal fluency, locating objects, detecting emotions, and sensitivity to touch, taste, and color (Halpern et al., 2007). Boys outperform girls in tests of spatial ability and complex math problems, though in math computation and overall math performance, boys and girls hardly differ (Else-

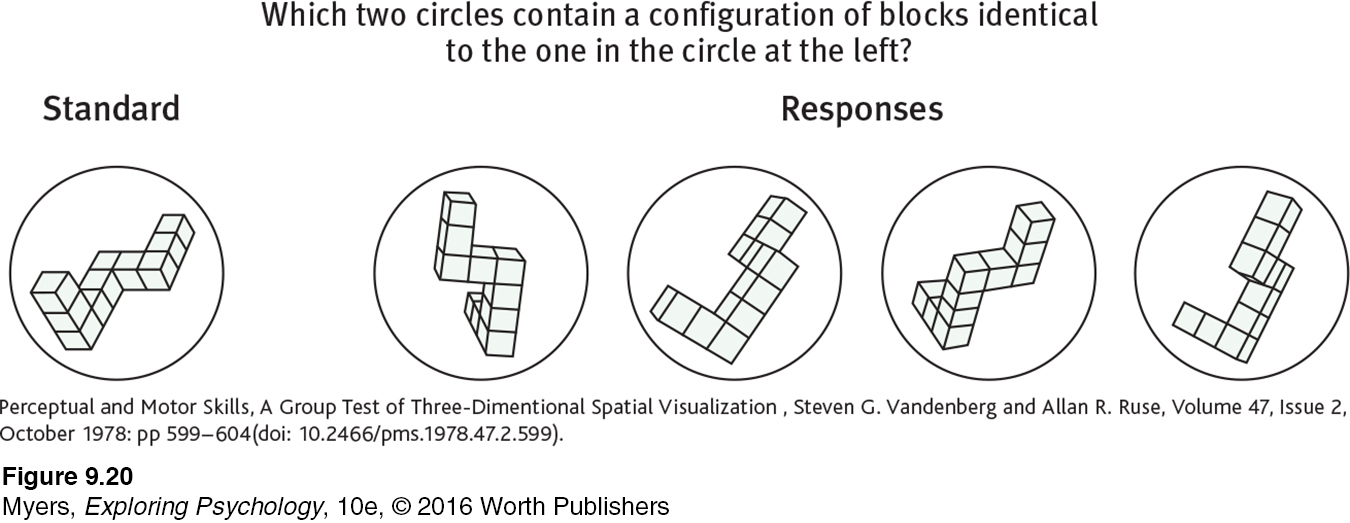

The most reliable male edge appears in spatial ability tests like the one shown in FIGURE 9.20 (Maeda & Yoon, 2013; Wei et al., 2012). The solution requires speedily rotating three-

But social expectations and opportunities also matter. In Asia and Russia, teenage girls have outperformed boys in an international science exam; in North America and Britain, boys have scored higher (Fairfield, 2012). More gender-

Racial and Ethnic Similarities and Differences

358

9-

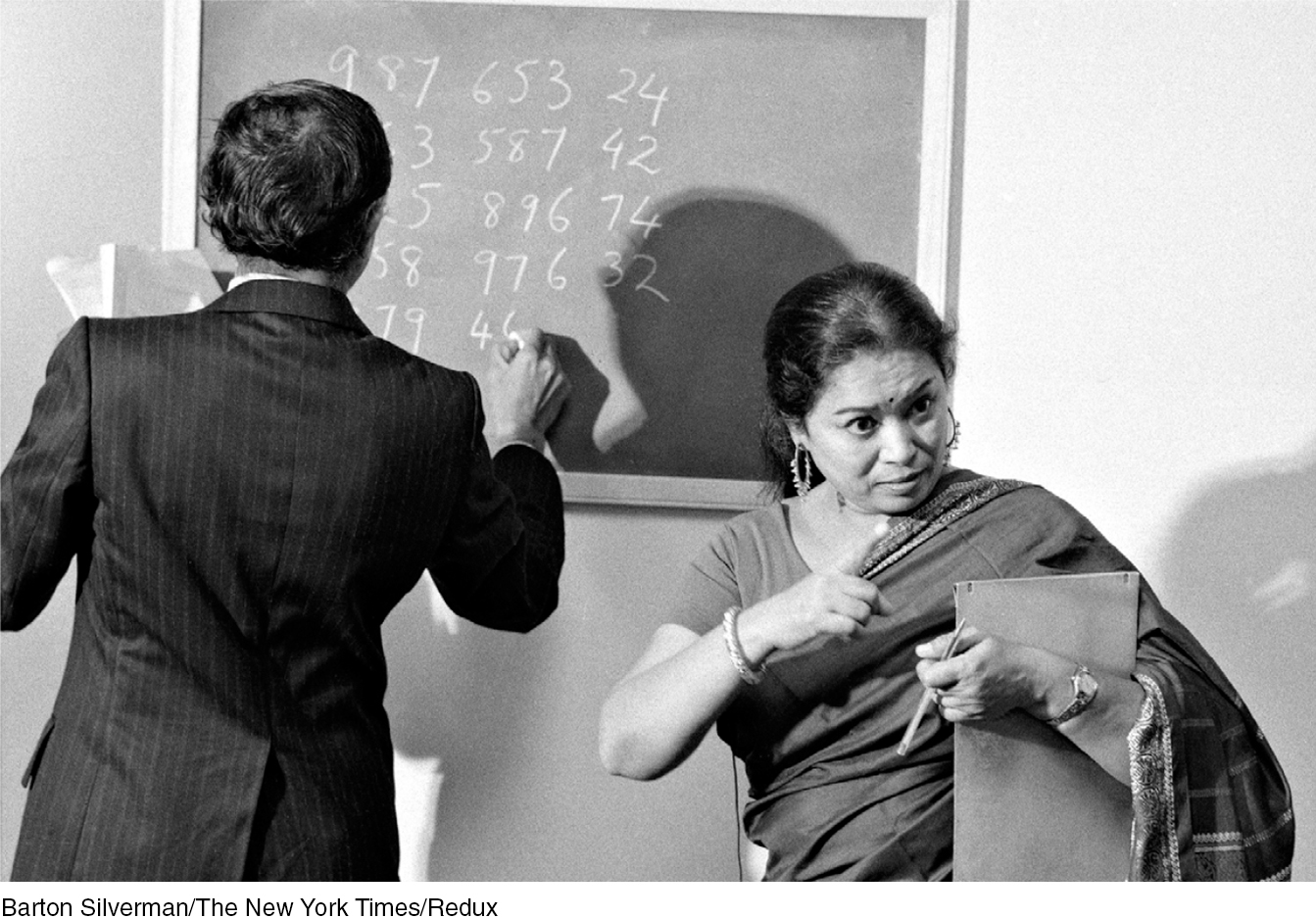

Fueling the group-

Racial and ethnic groups differ in their average intelligence test scores.

High-

scoring people (and groups) are more likely to attain high levels of education and income.

There are many group differences in average intelligence test scores. New Zealanders of European descent outscore native Maori New Zealanders. Israeli Jews outscore Israeli Arabs. Most Japanese outscore most Burakumin, a stigmatized Japanese minority. Those who can hear have outscored those born deaf (Braden, 1994; Steele, 1990; Zeidner, 1990). And White Americans have outscored Black Americans. This Black-

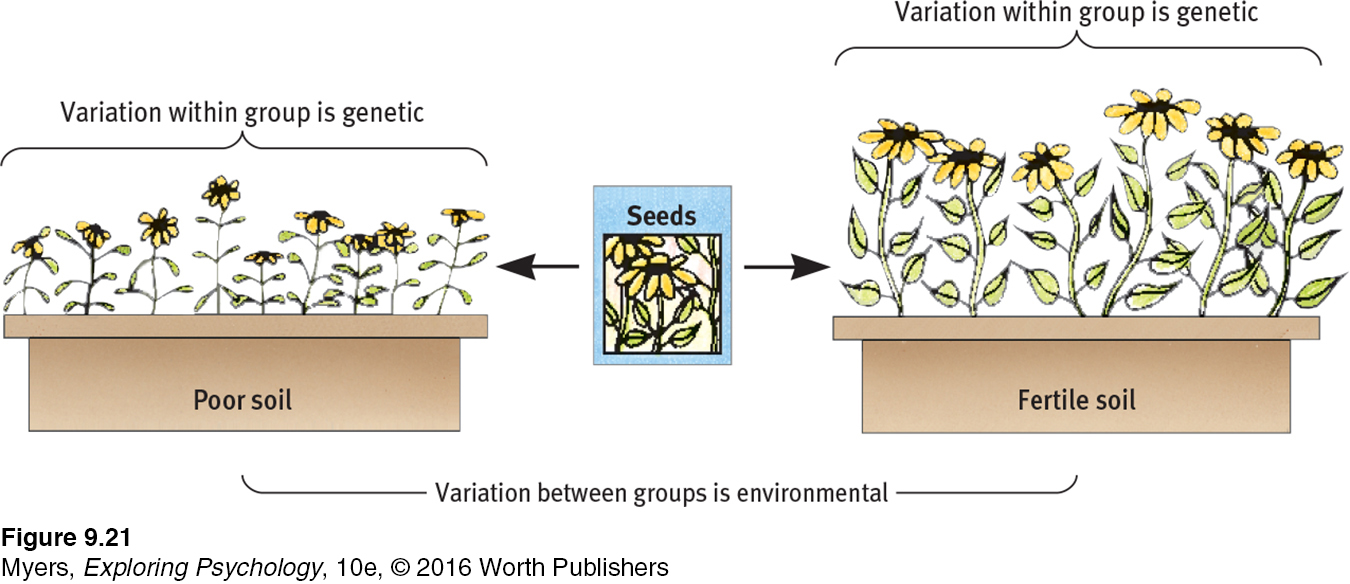

We have seen that heredity contributes to individual differences in intelligence. But group differences in a heritable trait may be entirely environmental. Consider one of nature’s experiments: Allow some children to grow up hearing their culture’s dominant language, while others, born deaf, do not. Then give both groups an intelligence test rooted in the dominant language, and (no surprise) those with expertise in that language will score highest. Although individual performance differences may be substantially genetic, the group difference is not (FIGURE 9.21).

Might the racial gap be similarly environmental? Consider:

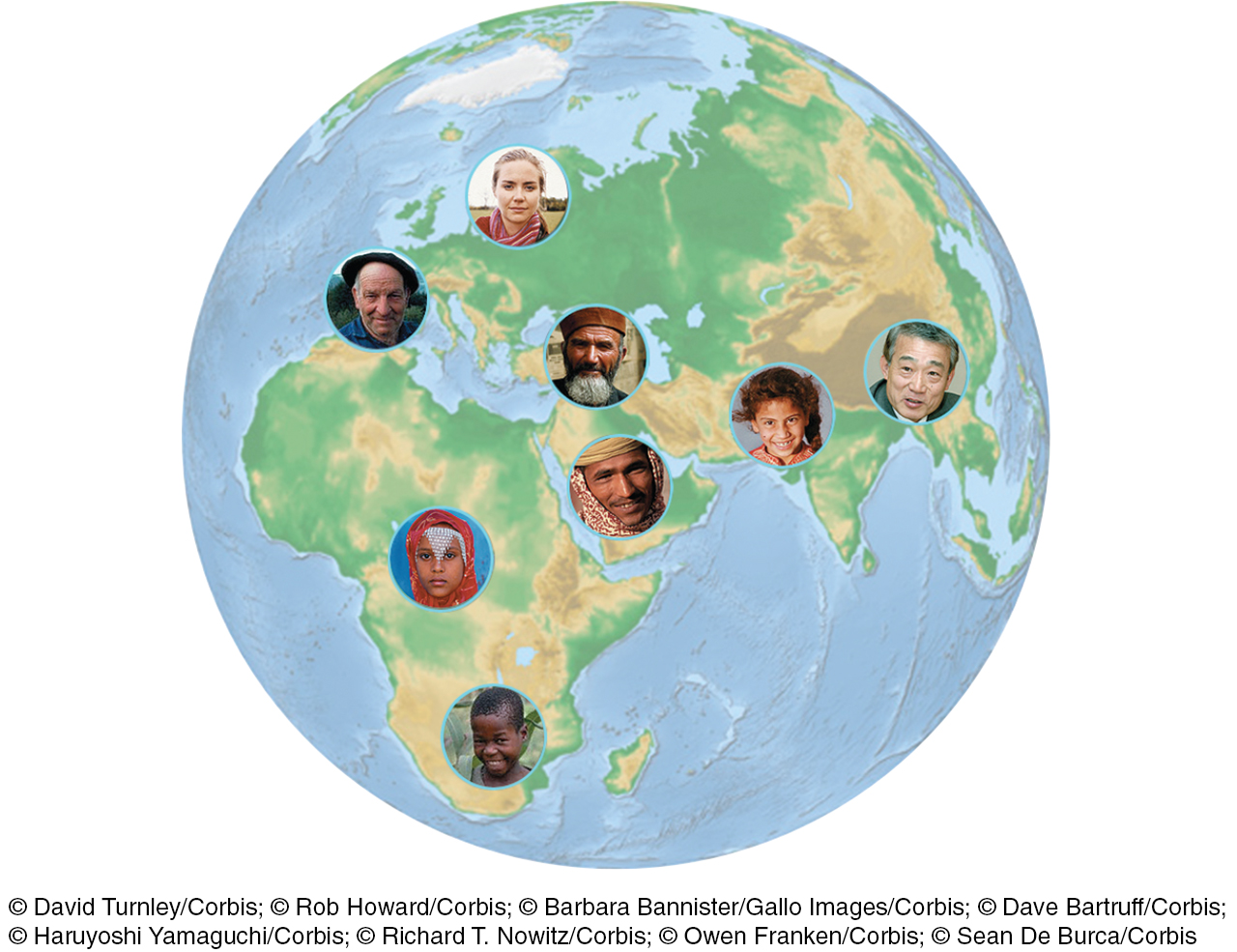

Genetics research reveals that under the skin, the races are remarkably alike. The average genetic difference between two Icelandic villagers or between two Kenyans greatly exceeds the group difference between Icelanders and Kenyans (Cavalli-

Race is not a neatly defined biological category. Many social scientists see race primarily as a social construction without well-

The intelligence test performance of today’s better-

359

When Blacks and Whites have or receive the same pertinent knowledge, they exhibit similar information-

Schools and culture matter. Countries whose economies create a large wealth gap between rich and poor tend also to have a large rich-

In different eras, different ethnic groups have experienced golden ages—

“Do not obtain your slaves from Britain, because they are so stupid and so utterly incapable of being taught.”

Cicero, 106–

RETRIEVE IT

Question

2fSnK7F1pWm8kBdidqvtN1V1wR4u/GvevThoJC4G43PbJw07mgbHJyy3s16jhd7u69A6QddZdNvLG2/3Pwm87CSxGwm+hLq9CLqtwqFspQnidkDlgwd1y6cMenR3PIo986xuNkreEKj3hMq1q3M5uJzL3bGg31lJiJQNuwxzSB91bXfxKa8E1uYk4MfUmTexuuSq+asWQnfpu4vS2eHiA7enHmtMDzmzuegIiETqu7fal//cF/tt5cEAfV5r6DI6AVg9nQ==The Question of Bias

360

9-

If one assumes that race is a meaningful concept, the debate over racial differences in intelligence divides into three camps (Hunt & Carlson, 2007):

There are genetically disposed racial differences in intelligence.

There are socially influenced racial differences in intelligence.

There are racial differences in test scores, but the tests are inappropriate or biased.

We have considered group differences from the first and second perspectives. Let’s turn now to the third: Are intelligence tests biased? The answer depends on the definition of bias we use.

Two Meanings of Bias

The scientific meaning of bias hinges on a test’s validity—

But we can also consider a test biased if it detects not only innate differences in intelligence but also performance differences caused by cultural experiences. This in fact happened to Eastern European immigrants in the early 1900s. Lacking the experience to answer questions about their new culture, many were classified as “feeble-

You may have read examples of intelligence test items that make assumptions (for example, that a cup goes with a saucer). Such items bias the test (in this case, against those who do not use saucers). Could such questions explain cultural differences in test performance? In such cases, tests can be a vehicle for discrimination, consigning potentially capable children (some of whom may have a different native language) to unchallenging classes and dead-

So, test-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

7iAutHCYiMlPW3PW8mP1iqGGA+NDULuqWzGfRJgswbcYb6do9finVuJuSjsIQtBU6Z9gB9F8u6FgR1inXraH/ysVTZtU3B94fZeu5bzm7R9KG8MBdqHvFB4w20XYxQRSJPpIbzdT9pKtSo7Nsxv0zcYAD2PLTx4O2fS+c9M/I5NGeFyZ/zCQXeWemvfdzHr2gWcsLNdcdTcAPGfAVdgmsPIisLI=Stereotype Threat

361

stereotype threat a self-

If, when taking an intelligence test or an exam, you are worried that your group or “type” often doesn’t do well, your self-

When Steven Spencer and his colleagues (1997) gave a difficult math test to equally capable men and women, women did not do as well—

Critics argue that stereotype threat does not fully account for Black-

“Math class is tough!”

“Teen talk” talking Barbie doll (introduced July 1992, recalled October 1992)

Steele (1995, 2010) concludes that telling students they probably won’t succeed (as is sometimes implied by remedial “minority support” programs) functions as a stereotype that can erode performance. Minority students in university programs that have challenged them to believe in their potential, to increase their sense of belonging, or to focus on the idea that intelligence is malleable and not fixed, have produced markedly higher grades and have had lower dropout rates (Walton & Cohen, 2011; Wilson, 2006).

These observations would not surprise psychologist Carol Dweck (2012a,b, 2015). She reports that believing intelligence is changeable fosters a growth mind-

362

Real world studies confirm that ability + opportunity + motivation = success. High school students’ math proficiency and college students’ grades reflect their aptitude but also their self-

“Almost all the joyful things of life are outside the measure of IQ tests.”

Madeleine L’Engle, A Circle of Quiet, 1972

* * *

Perhaps, then, our goals for tests of mental abilities should be threefold.

We should realize the benefits that intelligence testing pioneer Alfred Binet foresaw—

to enable schools to recognize who might profit most from early intervention. We must remain alert to Binet’s fear that intelligence test scores may be misinterpreted as literal measures of a person’s worth and potential.

We must remember that the competence that general intelligence tests sample is important; without such tests, those who decide on jobs and admissions would rely more on other considerations, such as personal opinion. But these tests reflect only one aspect of personal competence (Stanovich et al., 2013, 2014). Our practical intelligence and emotional intelligence matter, too, as do other forms of creativity, talent, and character.

“[Einstein] showed that genius equals brains plus tenacity squared.”

Walter Isaacson, “Einstein’s Final Quest,” 2009

The point to remember: There are many ways of being successful: Our differences are variations of human adaptability. Life’s great achievements result not only from “can do” abilities (and fair opportunity) but also from “will do” motivation. Competence + Diligence → Accomplishment.

What time is it now? When we asked you (in the section on overconfidence) to estimate how quickly you would finish this chapter, did you underestimate or overestimate?

RETRIEVE IT

Question

sCjVLVIjjSe4BNciFHpD7rAmN+VtIYp9EVEQXD21yviRYSPAlSb9maZ2wilizUkAmg1jn/HrLh3UNjnfEf/W3t/9Uqi1OLx3CODZ7zRtLyo0hYLN47e5+AdPj9THLEr0l164Q05CuPTbTXE1LjxwVZJlLfB2EqHxQZFBzXxAcl86/XqtmoIc5eb/ZVc3hg8dz6aWEzT/AbB1W7Y9Io+HxugEGllU2zPUzyKNlOrgE7CC0WB5vcfluQ==REVIEW Genetic and Environmental Influences on Intelligence

Learning Objectives

363

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

9oIU1NYzPMZkjNv3WCb7K2cnGQV5qoqZSbl9Pvtz3DnYKu1hFvZgCY6EaSxpQ4QYkCwLlQ6jh/iHlq9C3UOUs8cK/oeJlzyFyL5GE96Sem+wbUhkPFzR5Dc6QGDsB1WuMdsro+3Zy1UTT2sfiB7cqEMhAkGaqbSMrueG5YGsgEfzgh6F+ufXBnDIg2YrXMHxnZGW0iTsgUN5WFk3lTxJq1dxnNyl+9NNLOftAIS8E3Ujh7Rxsbfepa25QPGW2RsQexxv/Vg/IkZPTSf0Question

UzmTT2SNJzP/1LJZbSo5l8jhI0TroMlq3YmUI0Gh1mM6GpSLj3gLEf5iRrKHcq4AMXj8Qr2knAEu7vJ9HfQmKR7a1jLIk7HqUCCzEgizpAluX/nhasENDKfVi19MoCinCPbh3LJVPHCFXMq9Ypy9sFZEG6RyWulX5uOE/kTExgWhii3i7wkLr3JHa3goNFQUSH4e4ejcdktRQzd0Pa20iE51/ZGWEQ8y29+4/SYPbzLzHEJTXMpRejj3h0M=Question

OnjL8cY/CO0RgjH3jv6BoOKiDZL3T6MBup4xBEFZtSIMOx66nqQpUYrR3Cx/OH2xVX2fZ4rrtXt8mxu6Bs4rnyVFDtzsjYFiiSlwBzS0GPSEGueN619+cFylVG2yxPfmWU4jXE8NbjXJ/kuRRjcwnLnW5XTYDzS2o/JxzOjz96JTbz7uMaQIYst7ogCJJvazSpsOJj1nmDsx39oRLo5LDnNhvRC9fvSwFjtC08NANro=Question

FHnX0V/bTtTAhWveqcfvzt3J8aDGVEv3JZtRVS5GZ+cQs1ZXkddC+v2+CZ9pugKvgbrkzwxP9y21CTgSCHE/9+PbtPsdHfktKcDJaxFmJRR+zvRSWOvcwemRu/PW41hZx+Q1dw3nG4KIoomuJetsKq8ojdG+IkyVUheTTU2PZCpF7+nFLxSZ6WbtoM1+QaRpuZyCqnGdJ2loXdXjRdbSShFTSltI0hW9y1qvN3xOfRZgX7+DOpHjtAdopjM=Question

8blK+9zls9lvW5KtGacJTTYeEJZQA28Xem1UTAUOGB4gXCS0AwNjQOjiSSbcba284QJ+4bj5LSVjHhM0KKyhZ6exPJrMp4Vlc1ONH8Z6FjiCj/5amWQbKnnsWd6UnXPXQ2MKMHa4HhdCZgUQAClbg3AD2qpnA+XIHdc5CM/ozeLJ+kLcX/xunSC7tblzOpxqsoFkhod74ysLaH/GRU4nkMuHRXc=Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

IaaDn63ALsPvl+WNNC/6pW7R6Y9hTACtiRbpSQjxOIQ3qhZ1Wdt06tE11NwN97widUz9clLsMxPCBj8TYgBTAEKvFodplae5o4bAvn7GIfvFmXO4NeMrnEQhwz2Ic52Xx0jfmMk47nyczwKJAjzIosYrKJWDhABa06CIk5gKQ1lQPnS8z6Z2eJFXgGrQ0uRlysHQ8lP4ll2dg/OoG0TpZu6gfGtIPUjucxNcnN48/ZQfQuVhsQLRgch/7S+TI9GQMkf7N38ZCMOryw8tANP02JYWedY75ZlYoL3cAlmqNoKoOdI/wIFOjmcxZD42PdAKabqLny/erJoNYDemv3qsm2cXNNxROH8fYQ9K5rAhm87w/mSDPsSHhGdHunPezPaGIYsOjBX7xyzMQm8sbPuqse2ePsfChWX7tG0WgsZNvtBpciKQu/BAa4LEahzTfHn3KBeJu84BTCqkWLDSa5B1oflq78gjhiwhQKdBwRr4/7c9OIh0Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 9.23

qaYzlAhHKbibHUwv9kQhoS4eE04Wa+vi3tB7kX4O4c8Ev73SnD+YkKX/Ky6qZg6Tm2YmNx5zIoXYb234wEDqrcjeun6psKIVcVUIRhDh8s26cI6If26Q3ib1zDds/hEVmgtJo6g5Hw3mjyemGK/rPA99f+n5mm1uY/iD3lRVi8uwWolV2TVIIXYAoUQvBFS95CqiNo3IdgYFVVM6GJrUuRxDECl+a01GOf5id6s0lXOYbfAf/i69JdKZX6DNOLltmEX4Nc5TDXp2GqXgS6NtrDTOWgj/uEQ2sncEhg1WVk/qN6NL7TRT28gW5Qq8z9yJYTlyDb4uGNP28YvlhNbzTmh61DAfc25rQtt4HZryJX/wMiqzKaXCUmBj1zg9KS+GDjGrBkRTtw2xCK+9Rw37LNRyQUQbhxqfOodm8LALVG/n7ekvfRXufrXaITnWA33jpLwbNJFpQrxyIf9ZVeXsjadhxZFmbNg2iozeyBeL+E2hs74sSu1RciDs4huASJ0W9d9ZO9a+WW07U+oYEK4fFxt84wHdP52xXaBGGyIpRQqbNZXSSH5pEcdOyW86LqE2gmgq15//rs+/aSeK+4QaA603xkv0ApDsMjhIbWaUXqS0nxSxVhaiqpXk9Fjyd8mJQuestion 9.24

udA8N7R1DpHnsHj1cFjLgVZJwXQbBmsOdI82t47V3H3qpr0T3uBKRuxFXLw3tqan/GfRA4tluyt9VyFBvgtzH4HEpkcKME8eSKWUf6l+IRcDPw13LPlz7tFF56jZyrsWRCaj1yS/Lz6VHC+hFwEjesmSX6mdPgkEKNOQT4cAw1k3vatNhwfnrhD57VyGgoJ6LYHVpjjRIwNkHppt11qoCZOAMyspmpoNWseJQV5YBHzxU888LdASVy4Hzvapz1SDlAR+y0YP68PAEDsz+1craca/1EDgTk6Beuz123u8QzSmq/1DT2jxvgWtqgmxLxmlzhBQKlWmEZGHNjqk2EjIsMyPgZv6SCqfj6rZBixRi2gLQBG/FNw48Vc8Sko1sDhZSV5DjVWjiHDf6pXa1I4t6ZK+k9Wx2hh083pzBPpcX1NJwDth5DfPVJye4CVbufzM2CUU4IfhTsTrbMn0GGyqIjX+9871oDDyYMCOL+i+FPwFZRdNABHIMQvAGEnC1vRfYOlBh7sJbecdZjTegvTR45s4L8jpMRVdxu354YdEnP8VaNcte+r4LZ3a3EuZjqGtd26uRX1tn2s=Question 9.25

Yj247aO6X1YiUN3hbaAq+CA4gNhBcIz9aNV6WE1phYI5ADp9iIx6DKQaVvbDGJcvX29Rbsa6512M1kCMh548rP7iPIkCiKIsDdkL79xXTwd8Bf3eUTfp3fQ6BGPrAUdPXr14Qok4Hk2+f0Z3deHGbbyZ/jLH5UgeRftlXN6P5qbuzxIapgLmyhXimd0OsPT1if/cUs8SkY8sdY1CTS8zJEtFFv2C2MmEixRtrGrW7mib9hkw1paHk8aY3/oLVOF1rKePulXVzZV3hs3FgyeGsj7Q+ELBEMnsLJXWofUbR0HRGWSDrNHf2IbbVutpHD2pk3YHRxL8AkTXFjiEeNPcS9vZeaG6PZB9j66bbhv+MDohiZC2cYX2cCSHLNkdpfcX6aci+Qam6+Vxl+2xuvlHGnxaPknBAe+RRGrEQWyyKA1QZ6cdkf8uaaizVUDwMqsV+lbHHPpZ8iKa6AC3y+EQZGfZnT8VOWpG9xQTggsYjhg=Question 9.26

4. fHy8Vt+atfVWN/fnHD1hJGCz9uHo3eYl

can lead to poor performance on tests by undermining test-

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.