32.4 The Effects of Facial Expressions

32-

As William James (1890) struggled with feelings of depression and grief, he came to believe that we can control emotions by going “through the outward movements” of any emotion we want to experience. “To feel cheerful,” he advised, “sit up cheerfully, look around cheerfully, and act as if cheerfulness were already there.”

“Whenever I feel afraid

I hold my head erect

And whistle a happy tune.”

Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, The King and I, 1958

Studies of emotional effects of facial expressions reveal precisely what James might have predicted. Expressions not only communicate emotion, they also amplify and regulate it. In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Charles Darwin (1872) contended that “the free expression by outward signs of an emotion intensifies it… . He who gives way to violent gestures will increase his rage.”

Want to test Darwin’s hypothesis? Try this: Fake a big grin. Now scowl. Can you feel the “smile therapy” difference? Participants in dozens of experiments have felt a difference. James Laird and his colleagues (1974, 1984, 1989, 2014) subtly induced students to make a frowning expression by asking them to “contract these muscles” and “pull your brows together” (supposedly to help the researchers attach facial electrodes). The results? The students reported feeling a little angry, as do people who are facing the Sun (squinting activates the frowning muscles) (Marzoli, et al., 2013). So, too, for other basic emotions. For example, people reported feeling more fear than anger, disgust, or sadness when made to construct a fearful expression: “Raise your eyebrows. And open your eyes wide. Move your whole head back, so that your chin is tucked in a little bit, and let your mouth relax and hang open a little” (Duclos et al., 1989).

facial feedback effect the tendency of facial muscle states to trigger corresponding feelings such as fear, anger, or happiness.

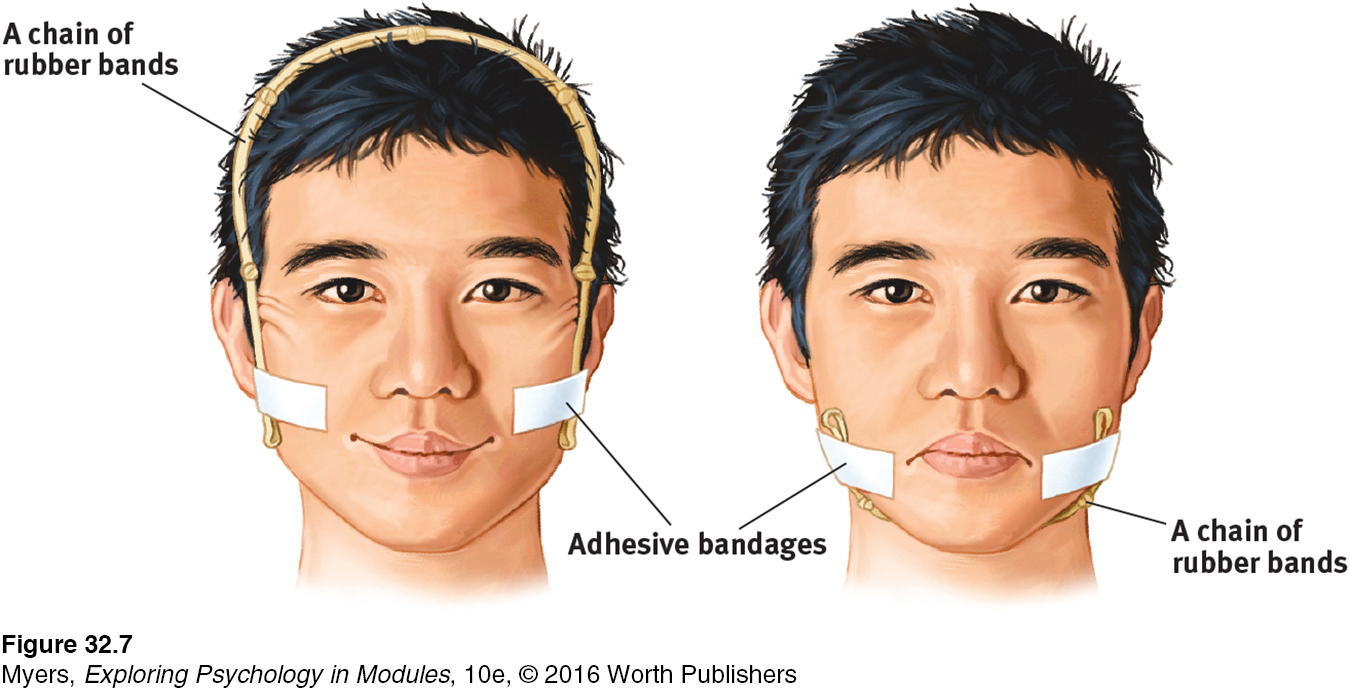

This facial feedback effect has been found many times, in many places, for many basic emotions (FIGURE 32.7 below). Just activating one of the smiling muscles by holding a pen in the teeth (rather than gently in the mouth, which produces a neutral expression) makes stressful situations less upsetting (Kraft & Pressman, 2012). A heartier smile—

A request from your authors: Smile often as you read this book.

RETRIEVE IT

402

So your face is more than a billboard that displays your feelings; it also feeds your feelings. No wonder some depressed patients reportedly felt better after Botox injections paralyzed their frowning muscles (Wollmer et al., 2012). Four months after treatment, they continued to report lower depression levels. Follow-

behavior feedback effect the tendency of behavior to influence our own and others’ thoughts, feelings, and actions.

With studies of bodily posture and vocal expressions, researchers have observed a broader behavior feedback effect (Flack, 2006; Snodgrass et al., 1986). You can duplicate the participants’ experience: Walk for a few minutes with short, shuffling steps, keeping your eyes downcast. Now walk around taking long strides, with your arms swinging and your eyes looking straight ahead. Can you feel your mood shift? Going through the motions awakens the emotions.

Likewise, people perceive ambiguous behaviors differently depending on which finger they move up and down while reading a story. (This was said to be a study of the effect of using finger muscles “located near the reading muscles on the motor cortex.”) If participants read the story while moving an extended middle finger, the story behaviors seemed more hostile. If read with a thumb up, they seemed more positive. Hostile gestures prime hostile perceptions (Chandler & Schwarz, 2009; Goldin-

You can use your understanding of feedback effects to become more empathic: Let your own face mimic another person’s expression. Acting as another acts helps us feel what another feels (Vaughn & Lanzetta, 1981). Losing this ability to mimic others can leave us struggling to make emotional connections, as one social worker with Moebius syndrome, a rare facial paralysis disorder, discovered while working with Hurricane Katrina refugees: When people made a sad expression, “I wasn’t able to return it. I tried to do so with words and tone of voice, but it was no use. Stripped of the facial expression, the emotion just dies there, unshared” (Carey, 2010).

403

Our natural mimicry of others’ emotions helps explain why emotions are contagious (Dimberg et al., 2000; Neumann & Strack, 2000). Positive, upbeat Facebook posts create a ripple effect, leading Facebook friends to also express more positive emotions (Kramer, 2012).

* * *

We have seen how our motivated behaviors, triggered by the forces of nature and nurture, frequently go hand in hand with significant emotional responses. Our often-