30.1 The Physiology of Hunger

30-

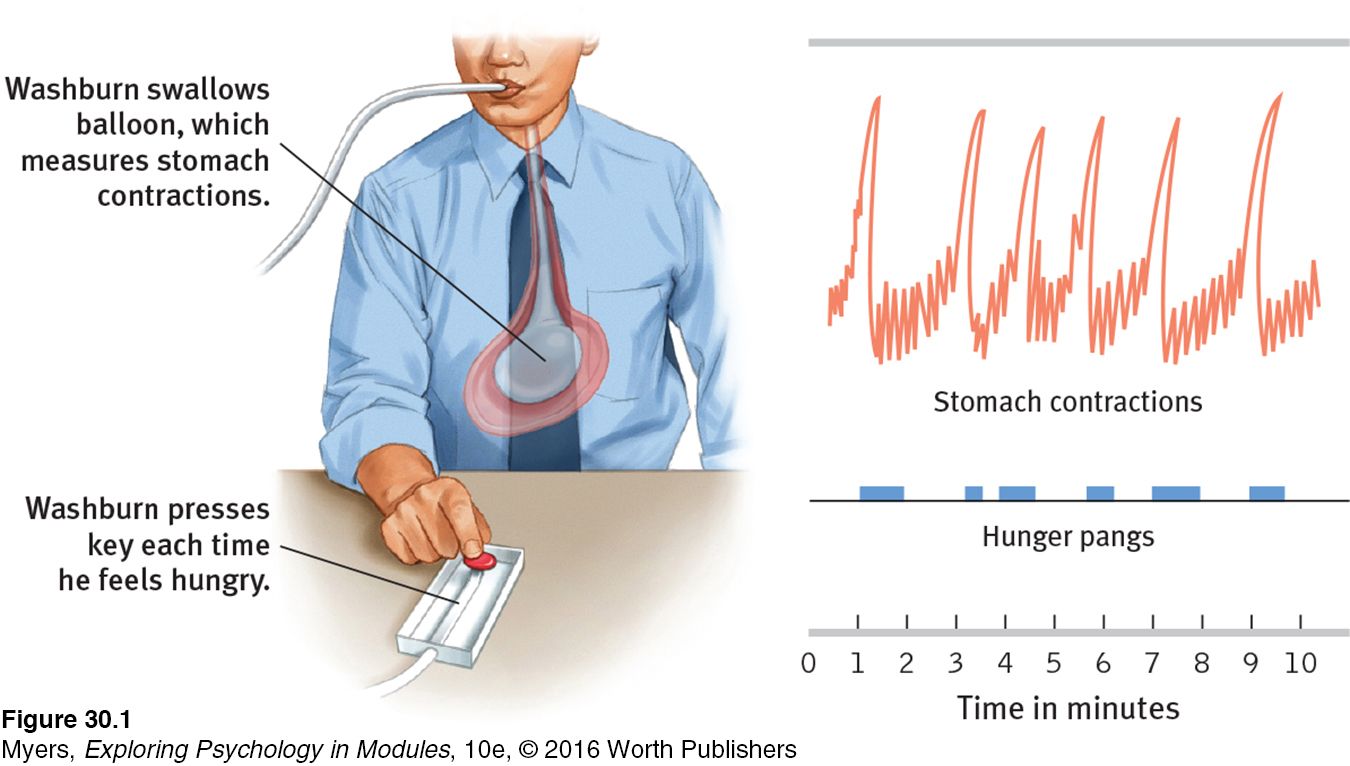

Deprived of a normal food supply, Keys’ semistarved volunteers were clearly hungry. But what precisely triggers hunger? Is it the pangs of an empty stomach? So it seemed to A. L. Washburn. Working with Walter Cannon (Cannon & Washburn, 1912), Washburn agreed to swallow a balloon attached to a recording device (FIGURE 30.1). When inflated to fill his stomach, the balloon transmitted his stomach contractions. Washburn supplied information about his feelings of hunger by pressing a key each time he felt a hunger pang. The discovery: Washburn was indeed having stomach contractions whenever he felt hungry.

Can hunger exist without stomach pangs? To answer that question, researchers removed some rats’ stomachs and created a direct path to their small intestines (Tsang, 1938). Did the rats continue to eat? Indeed they did. Some hunger similarly persists in humans whose ulcerated or cancerous stomachs have been removed. So the pangs of an empty stomach are not the only source of hunger. What else might trigger hunger?

Body Chemistry and the Brain

379

379

glucose the form of sugar that circulates in the blood and provides the major source of energy for body tissues. When its level is low, we feel hunger.

Somehow, somewhere, your body is keeping tabs on the energy it takes in and the energy it uses. If this weren’t true, you would be unable to maintain a stable body weight. A major source of energy in your body is the blood sugar glucose. If your blood glucose level drops, you won’t consciously feel the lower blood sugar, but your stomach, intestines, and liver will signal your brain to motivate eating. Your brain, which is automatically monitoring your blood chemistry and your body’s internal state, will then trigger hunger.

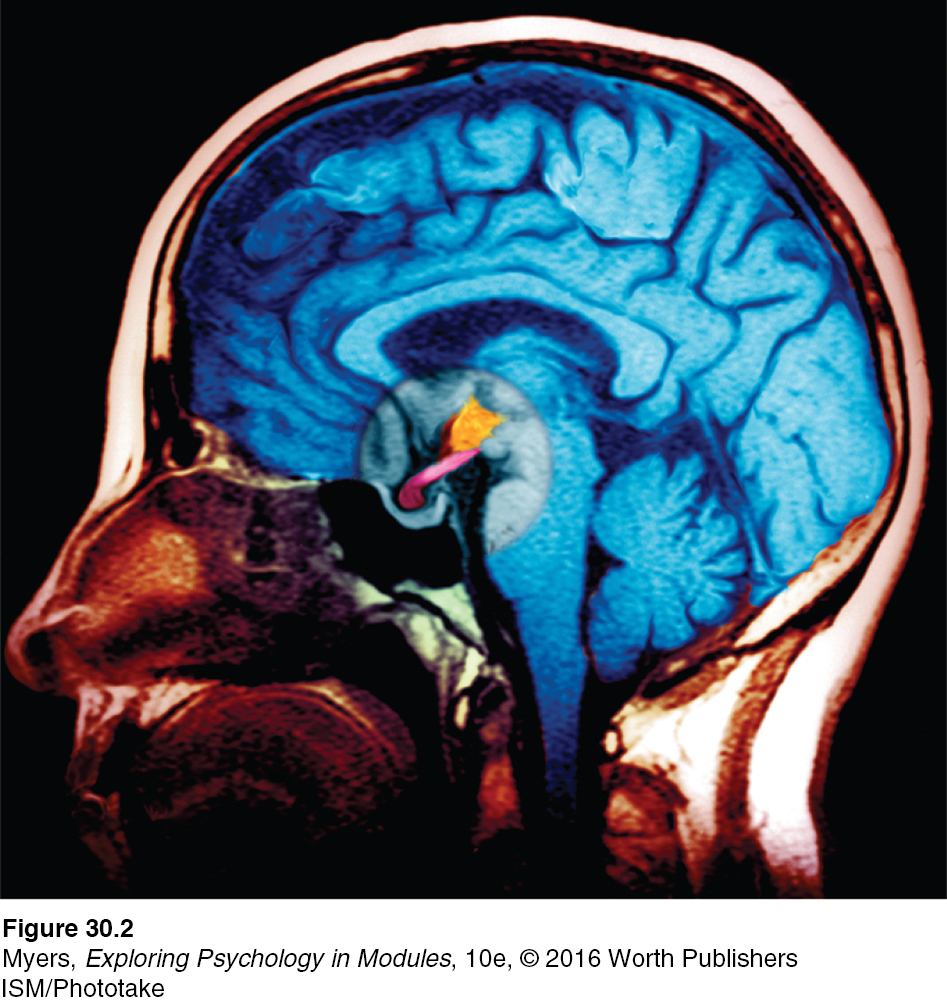

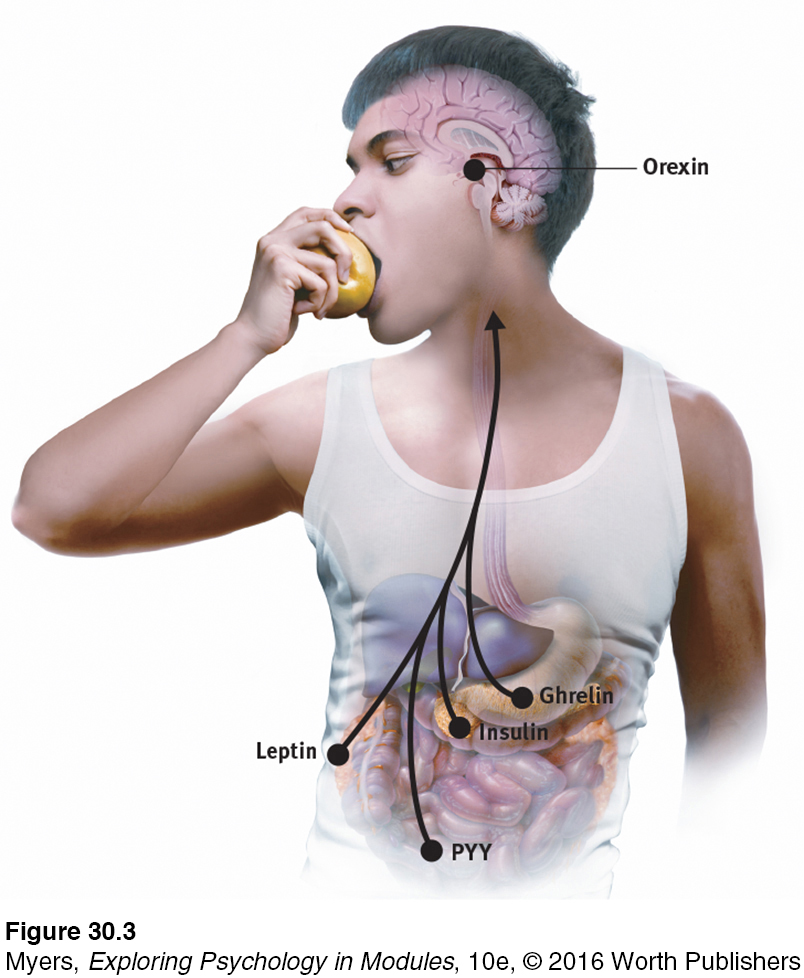

How does the brain integrate these messages and sound the alarm? The work is done by several neural areas, some housed deep in the brain within the hypothalamus, a neural traffic intersection (FIGURE 30.2). For example, one neural arc (called the arcuate nucleus) has a center that secretes appetite-

Blood vessels connect the hypothalamus to the rest of the body, so it can respond to our current blood chemistry and other incoming information. One of its tasks is monitoring levels of appetite hormones, such as ghrelin, a hunger-

• Ghrelin: Hormone secreted by empty stomach; sends “I’m hungry” signals to the brain.

• Insulin: Hormone secreted by pancreas; controls blood glucose.

• Leptin: Protein hormone secreted by fat cells; when abundant, causes brain to increase metabolism and decrease hunger.

• Orexin: Hunger-

• PYY: Digestive tract hormone; sends “I’m not hungry” signals to the brain.

set point the point at which your “weight thermostat” is supposedly set. When your body falls below this weight, increased hunger and a lowered metabolic rate may combine to restore the lost weight.

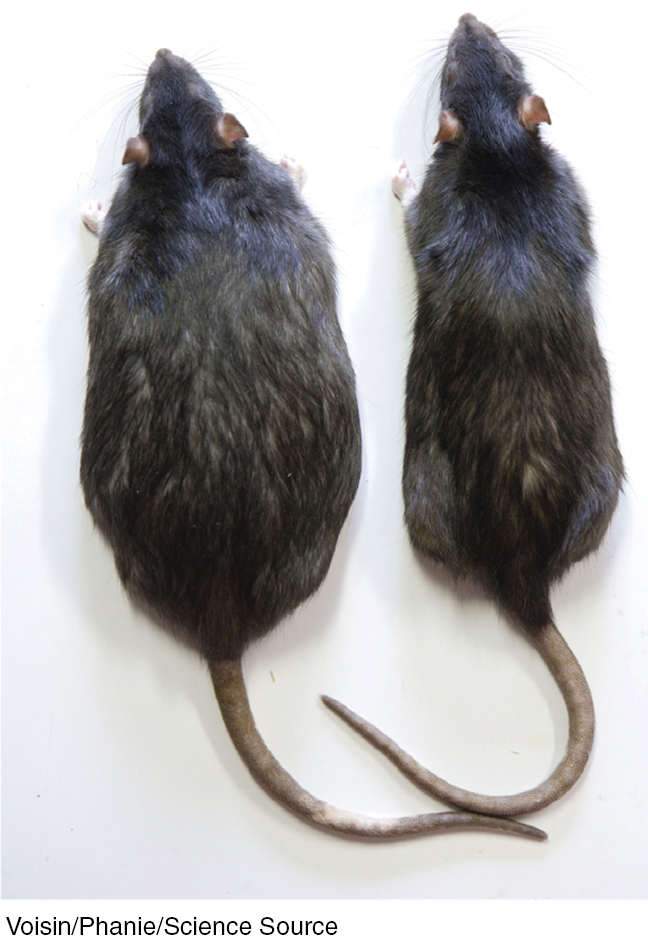

The interaction of appetite hormones and brain activity suggests that the body has some sort of “weight thermostat.” When semistarved rats fall below their normal weight, this system signals the body to restore the lost weight. Fat cells cry out (so to speak) “Feed me!” and grab glucose from the bloodstream (Ludwig & Friedman, 2014). Hunger increases and energy output decreases. In this way, rats (and humans) tend to hover around a stable weight, or set point, influenced in part by heredity (Keesey & Corbett, 1983).

For an interactive and visual tutorial on the brain and eating, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Hunger and the Fat Rat.

For an interactive and visual tutorial on the brain and eating, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Hunger and the Fat Rat.

basal metabolic rate the body’s resting rate of energy expenditure.

380

We humans (and other species, too) vary in our basal metabolic rate, a measure of how much energy we use to maintain basic body functions when our body is at rest. But we share a common response to decreased food intake: Our basal metabolic rate drops, as it did for participants in Keys’ experiment. After 24 weeks of semistarvation, they stabilized at three-

Some researchers have suggested that the idea of a biologically fixed set point is too rigid to explain some things. One thing it doesn’t address is that slow, sustained changes in body weight can alter a person’s set point (Assanand et al., 1998). Another is that when we have unlimited access to a wide variety of tasty foods, we tend to overeat and gain weight (Raynor & Epstein, 2001). And set points don’t explain why psychological factors influence hunger. For all these reasons, some prefer the looser term settling point to indicate the level at which a person’s weight settles in response to caloric intake and energy use. As we will see next, these factors are influenced by environment as well as biology.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Hunger occurs in response to lg05kNDUDyk= (low/high) blood glucose and y7/vtewiIOWV+gAS (low/high) levels of ghrelin.