9.2 Types of Psychoactive Drugs

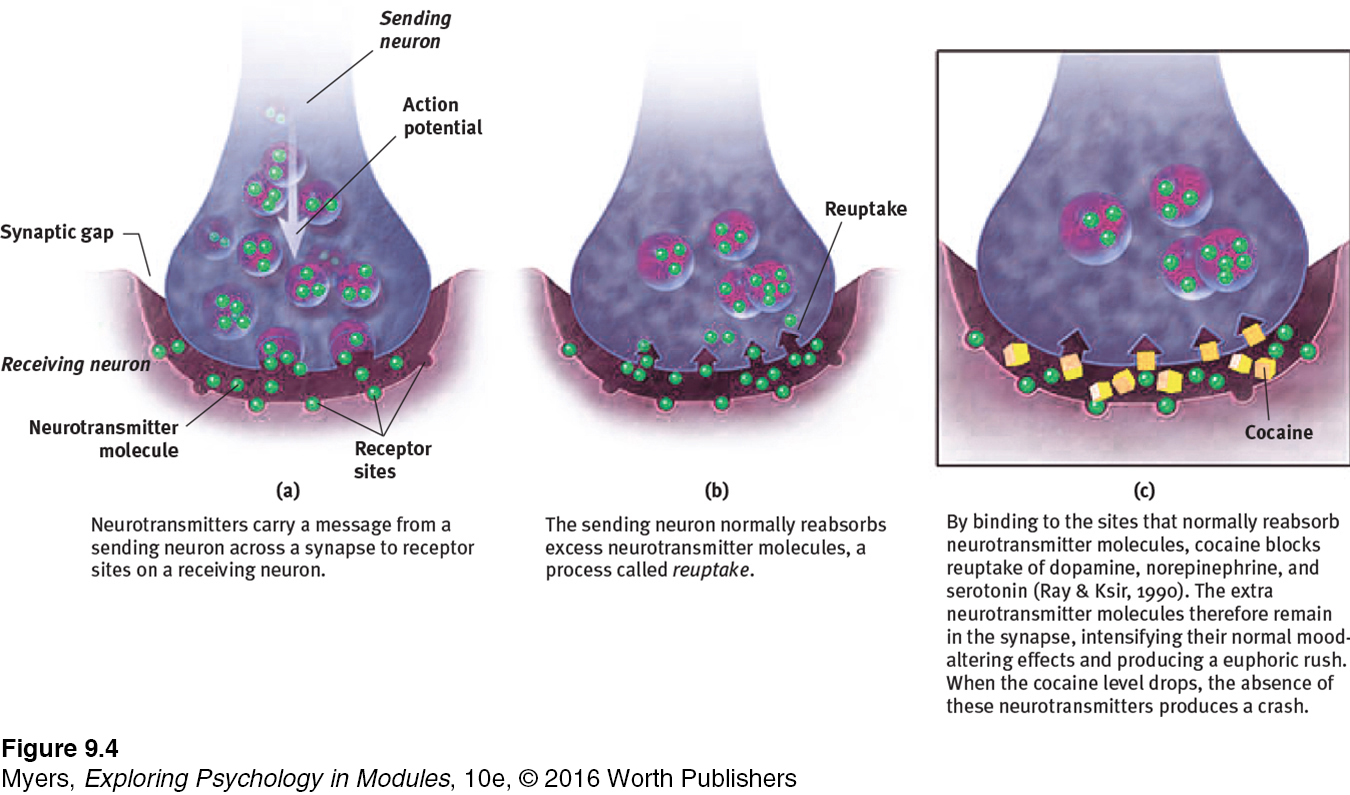

The three major categories of psychoactive drugs are depressants, stimulants, and hallucinogens. All do their work at the brain’s synapses, stimulating, inhibiting, or mimicking the activity of the brain’s own chemical messengers, the neurotransmitters.

Depressants

9-

depressants drugs (such as alcohol, barbiturates, and opiates) that reduce neural activity and slow body functions.

Depressants are drugs such as alcohol, barbiturates (tranquilizers), and opiates that calm neural activity and slow body functions.

ALCOHOL True or false? In small amounts, alcohol is a stimulant. False. Low doses of alcohol may, indeed, enliven a drinker, but they do so by acting as a disinhibitor—

alcohol use disorder (popularly known as alcoholism) alcohol use marked by tolerance, withdrawal, and a drive to continue problematic use.

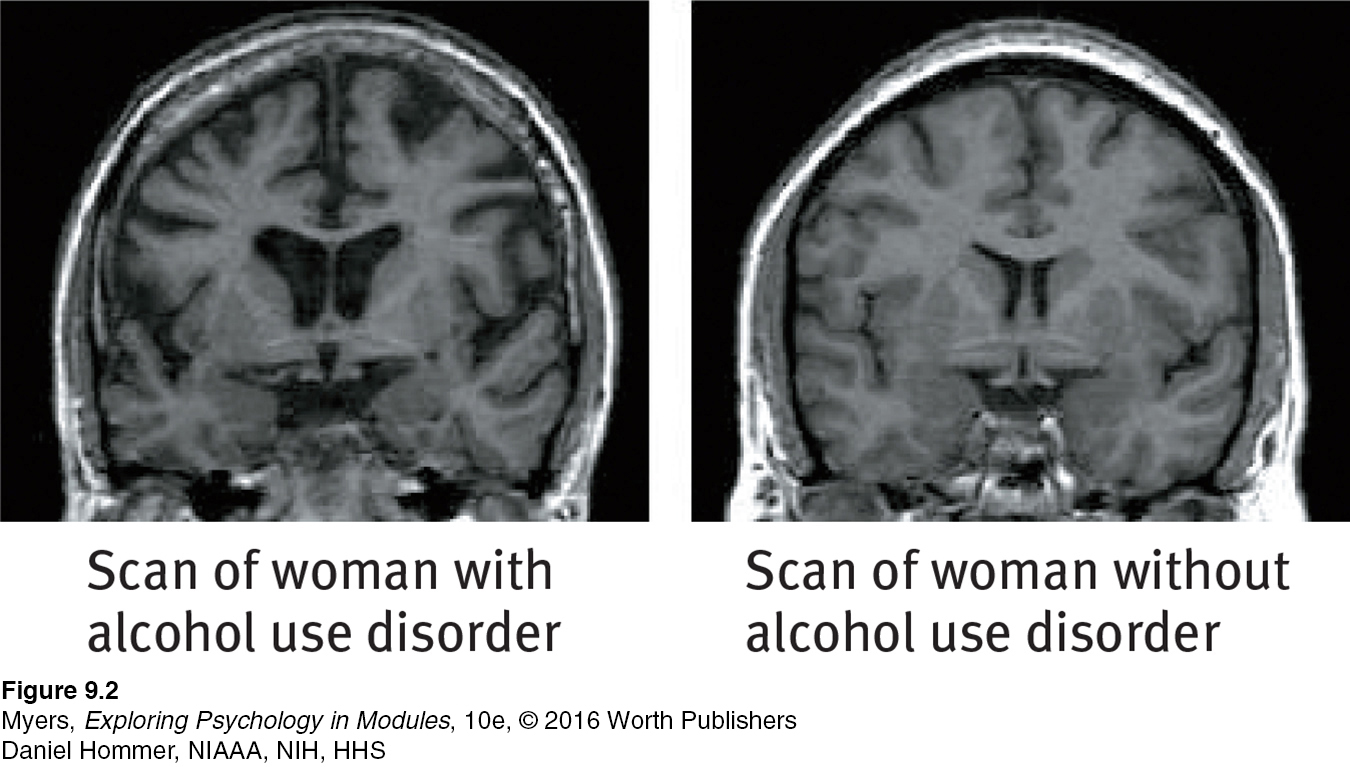

The prolonged and excessive drinking that characterizes alcohol use disorder can shrink the brain (FIGURE 9.2). Girls and young women (who have less of a stomach enzyme that digests alcohol) can become addicted to alcohol more quickly than boys and young men, and they are at risk for lung, brain, and liver damage at lower consumption levels (CASA, 2003).

SLOWED NEURAL PROCESSING Low doses of alcohol relax the drinker by slowing sympathetic nervous system activity. Larger doses cause reactions to slow, speech to slur, and skilled performance to deteriorate. Paired with sleep deprivation, alcohol is a potent sedative. Add these physical effects to lowered inhibitions, and the result can be deadly. Worldwide, several hundred thousand lives are lost each year in alcohol-

107

MEMORY DISRUPTION Alcohol can disrupt memory formation, and heavy drinking can have long-

REDUCED SELF-

Reduced self-

EXPECTANCY EFFECTS As with other drugs, expectations influence behavior. When people believe that alcohol affects social behavior in certain ways, and believe that they have been drinking alcohol, they will behave accordingly (Moss & Albery, 2009). In a classic experiment, researchers gave Rutgers University men (who had volunteered for a study on “alcohol and sexual stimulation”) either an alcoholic or a nonalcoholic drink (Abrams & Wilson, 1983). (Both had strong tastes that masked any alcohol.) After watching an erotic movie clip, the men who thought they had consumed alcohol were more likely to report having strong sexual fantasies and feeling guilt free. Being able to attribute their sexual responses to alcohol released their inhibitions—

So, alcohol’s effect lies partly in that powerful sex organ, the mind. Fourteen “intervention studies” have educated college drinkers about that very point (Scott-

barbiturates drugs that depress central nervous system activity, reducing anxiety but impairing memory and judgment.

BARBITURATES Like alcohol, the barbiturate drugs, or tranquilizers, depress nervous system activity. Barbiturates such as Nembutal, Seconal, and Amytal are sometimes prescribed to induce sleep or reduce anxiety. In larger doses, they can impair memory and judgment. If combined with alcohol—

opiates opium and its derivatives, such as morphine and heroin; depress neural activity, temporarily lessening pain and anxiety.

OPIATES The opiates—opium and its derivatives—

108

RETRIEVE IT

Question

TmLos7FjIQ4j8iPHI4OsOHlWWEkjvlmQMn3s5R9Qx4OduLvywAb01q5X4ilspkL/7BOfC3HSla7xUojwb/rBhA3maNsNBVglpiaGoWPgKPuaETlB7y9hN286QzFvyiXNQuestion

Alcohol, barbiturates, and opiates are all in a class of drugs called 8GJ8udVtaaoFHVrPqEswmQ== .

Stimulants

9-

stimulants drugs (such as caffeine, nicotine, and the more powerful amphetamines, cocaine, Ecstasy, and methamphetamine) that excite neural activity and speed up body functions.

A stimulant excites neural activity and speeds up bodily functions. Pupils dilate, heart and breathing rates increase, and blood sugar levels rise, causing a drop in appetite. Energy and self-

amphetamines drugs that stimulate neural activity, causing accelerated body functions and associated energy and mood changes.

Stimulants include caffeine, nicotine, cocaine, Ecstasy, the amphetamines, and methamphetamine. People use stimulants to feel alert, lose weight, or boost mood or athletic performance. Unfortunately, stimulants can be addictive, as you may know if you are one of the many who use caffeine daily in your coffee, tea, soda, or energy drinks. Cut off from your usual dose, you may crash into fatigue, headaches, irritability, and depression (Silverman et al., 1992). A mild dose of caffeine typically lasts three or four hours, which—

nicotine a stimulating and highly addictive psychoactive drug in tobacco.

NICOTINE Cigarettes, e-

The lost lives from these dynamite-

Smoke a cigarette and nature will charge you 12 minutes—

“Smoking cures weight problems … eventually.”

Comedian-

Tobacco products are as powerfully and quickly addictive as heroin and cocaine. Attempts to quit even within the first weeks of smoking often fail (DiFranza, 2008). As with other addictions, smokers develop tolerance, and quitting causes withdrawal symptoms, including craving, insomnia, anxiety, irritability, and distractibility. Nicotine-

For HIV patients who smoke, the virus is now much less lethal than the smoking (Helleberg et al., 2013).

109

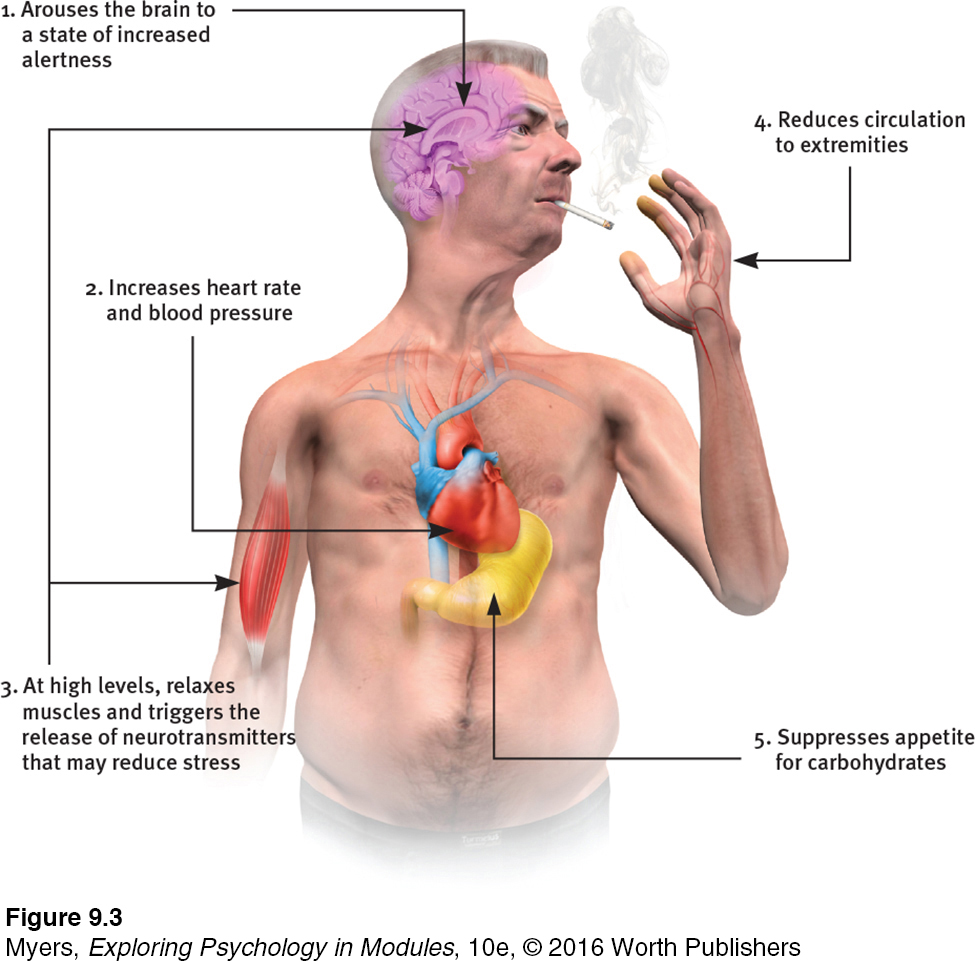

All it takes to relieve this aversive state is a single puff on a cigarette. Within 7 seconds, a rush of nicotine signals the central nervous system to release a flood of neurotransmitters (FIGURE 9.3). Epinephrine and norepinephrine diminish appetite and boost alertness and mental efficiency. Dopamine and opioids temporarily calm anxiety and reduce sensitivity to pain (Ditre et al., 2011; Scott et al., 2004). Thus, ex-

These rewards keep people smoking, even among the 3 in 4 smokers who wish they could stop (Newport, 2013). Each year, fewer than 1 in 7 smokers who want to quit will be able to resist. Even those who know they are committing slow-

Humorist Dave Barry (1995) recalling why he smoked his first cigarette the summer he turned 15: “Arguments against smoking: ‘It’s a repulsive addiction that slowly but surely turns you into a gasping, gray-

Nevertheless, repeated attempts seem to pay off. Half of all Americans who have ever smoked have quit, sometimes aided by a nicotine replacement drug and with encouragement from a counselor or support group. Success is equally likely whether smokers quit abruptly or gradually (Fiore et al., 2008; Lichtenstein et al., 2010; Lindson et al., 2010). For those who endure, the acute craving and withdrawal symptoms gradually dissipate over the ensuing 6 months (Ward et al., 1997). After a year’s abstinence, only 10 percent will relapse in the next year (Hughes et al., 2010). These nonsmokers may live not only healthier but also happier lives. Smoking correlates with higher rates of depression, chronic disabilities, and divorce (Doherty & Doherty, 1998; Edwards & Kendler, 2012; Vita et al., 1998). Healthy living seems to add both years to life and life to years.

110

RETRIEVE IT

Question

NtNmxDdKH3LpuM0wE7JSsaWMfxG724hisqKWN6+ljtnt//714IgXfOTWcvlkCKXj05MoifWgd42gERql+avlUNuUCFDoLCotmpZXhUpTxijn2lUykH7kdxhamKsZGt1ucocaine a powerful and addictive stimulant derived from the coca plant; produces temporarily increased alertness and euphoria.

COCAINE The recipe for Coca-

“Cocaine makes you a new man. And the first thing that new man wants is more cocaine.”

Comedian George Carlin (1937-

In situations that trigger aggression, ingesting cocaine may heighten reactions. Caged rats fight when given foot shocks, and they fight even more when given cocaine and foot shocks. Likewise, humans who voluntarily ingest high doses of cocaine in laboratory experiments impose higher shock levels on a presumed opponent than do those receiving a placebo (Licata et al., 1993). Cocaine use may also lead to emotional disturbances, suspiciousness, convulsions, cardiac arrest, or respiratory failure.

In national surveys, 3 percent of U.S. high school seniors and 6 percent of British 18-

Cocaine’s psychological effects depend in part on the dosage and form consumed, but the situation and the user’s expectations and personality also play a role. Given a placebo, cocaine users who thought they were taking cocaine often had a cocaine-

methamphetamine a powerfully addictive drug that stimulates the central nervous system, with accelerated body functions and associated energy and mood changes; over time, appears to reduce baseline dopamine levels.

111

METHAMPHETAMINE Methamphetamine is chemically related to its parent drug, amphetamine (NIDA, 2002, 2005), but has greater effects. Methamphetamine triggers the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine, which stimulates brain cells that enhance energy and mood, leading to 8 hours or so of heightened energy and euphoria. Its aftereffects may include irritability, insomnia, hypertension, seizures, social isolation, depression, and occasional violent outbursts (Homer et al., 2008). Over time, methamphetamine may reduce baseline dopamine levels, leaving the user with depressed functioning.

Ecstasy (MDMA) a synthetic stimulant and mild hallucinogen. Produces euphoria and social intimacy, but with short-

ECSTASY Ecstasy, a street name for MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine, also known in its powder form as “Molly”), is both a stimulant and a mild hallucinogen. As an amphetamine derivative, Ecstasy triggers dopamine release, but its major effect is releasing stored serotonin and blocking its reuptake, thus prolonging serotonin’s feel-

During the 1990s, Ecstasy’s popularity soared as a “club drug” taken at nightclubs and all-

Hallucinogens

9-

hallucinogens psychedelic (“mind-

Hallucinogens distort perceptions and evoke sensory images in the absence of sensory input (which is why these drugs are also called psychedelics, meaning “mind-

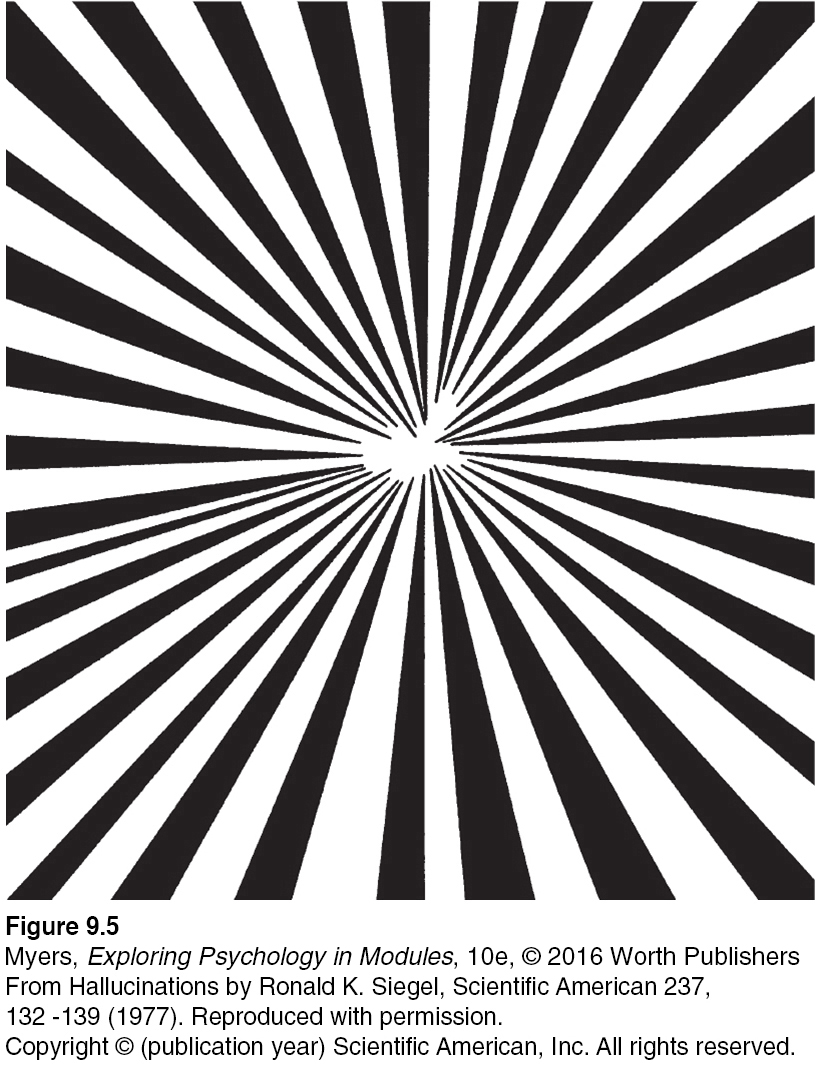

Whether provoked to hallucinate by drugs, loss of oxygen, or extreme sensory deprivation, the brain hallucinates in basically the same way (Siegel, 1982). The experience typically begins with simple geometric forms, such as a lattice, cobweb, or spiral. The next phase consists of more meaningful images; some may be superimposed on a tunnel or funnel, others may be replays of past emotional experiences. As the hallucination peaks, people frequently feel separated from their body and experience dreamlike scenes so real that they may become panic-

near-death experience an altered state of consciousness reported after a close brush with death (such as cardiac arrest); often similar to drug-

112

These sensations are strikingly similar to the near-death experience, an altered state of consciousness reported by about 10 to 15 percent of patients revived from cardiac arrest (Agrillo, 2011; Greyson, 2010; Parnia et al., 2014). Many describe visions of tunnels (FIGURE 9.5), bright lights or beings of light, a replay of old memories, and out-

LSD a powerful hallucinogenic drug; also known as acid (lysergic acid diethylamide).

LSD Chemist Albert Hofmann created—

The emotions of an LSD trip range from euphoria to detachment to panic. Users’ current mood and expectations (their “high hopes”) color the emotional experience, but the perceptual distortions and hallucinations have some commonalities.

THC the major active ingredient in marijuana; triggers a variety of effects, including mild hallucinations.

MARIJUANA Marijuana leaves and flowers contain THC (delta-

The straight dope on marijuana: It is a mild hallucinogen, amplifying sensitivity to colors, sounds, tastes, and smells. But like alcohol, marijuana relaxes, disinhibits, and may produce a euphoric high. Both alcohol and marijuana impair the motor coordination, perceptual skills, and reaction time necessary for safely operating an automobile or other machine. “THC causes animals to misjudge events,” reported Ronald Siegel (1990, p. 163). “Pigeons wait too long to respond to buzzers or lights that tell them food is available for brief periods; and rats turn the wrong way in mazes.”

Marijuana and alcohol also differ. The body eliminates alcohol within hours. THC and its by-

A marijuana user’s experience can vary with the situation. If the person feels anxious or depressed, marijuana may intensify the feelings. The more often the person uses marijuana, especially during adolescence, the greater the risk of anxiety, depression, or addiction (Bambico et al., 2010; Hurd et al., 2013; Murray et al., 2007).

Researchers are studying and debating marijuana’s effect on the brain and cognition. Some evidence indicates that marijuana disrupts memory formation (Bossong et al., 2012). Such cognitive effects outlast the period of smoking (Messinis et al., 2006). Heavy adult use for over 20 years has been associated with a shrinkage of brain areas that process memories and emotions (Filbey et al., 2014; Yücel et al., 2008). One study, which has tracked more than 1000 New Zealanders from birth, found that the IQ scores of persistent marijuana users before age 18 predicted lower adult intelligence (Meier et al., 2012). Other researchers are unconvinced that marijuana smoking harms the brain (Rogeberg, 2013; Weiland et al., 2015).

113

In some cases, legal medical marijuana use has been granted to relieve the pain and nausea associated with diseases such as AIDS and cancer (Munsey, 2010; Watson et al., 2000). In such cases, the Institute of Medicine recommends delivering the THC with medical inhalers. Marijuana smoke, like cigarette smoke, is toxic and can cause cancer, lung damage, and pregnancy complications (BLF, 2012).

* * *

Despite their differences, the psychoactive drugs summarized in TABLE 9.2 share a common feature: They trigger negative aftereffects that offset their immediate positive effects and grow stronger with repetition. And that helps explain both tolerance and withdrawal. As the opposing, negative aftereffects grow stronger, it takes larger and larger doses to produce the desired high (tolerance), causing the aftereffects to worsen in the drug’s absence (withdrawal). This in turn creates a need to switch off the withdrawal symptoms by taking yet more of the drug.

A Guide to Selected Psychoactive Drugs

| Drug | Type | Pleasurable Effects | Negative Aftereffects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Depressant | Initial high followed by relaxation and disinhibition | Depression, memory loss, organ damage, impaired reactions |

| Heroin | Depressant | Rush of euphoria, relief from pain | Depressed physiology, agonizing withdrawal |

| Caffeine | Stimulant | Increased alertness and wakefulness | Anxiety, restlessness, and insomnia in high doses; uncomfortable withdrawal |

| Nicotine | Stimulant | Arousal and relaxation, sense of well- |

Heart disease, cancer |

| Cocaine | Stimulant | Rush of euphoria, confidence, energy | Cardiovascular stress, suspiciousness, depressive crash |

| Methamphetamine | Stimulant | Euphoria, alertness, energy | Irritability, insomnia, hypertension, seizures |

| Ecstasy (MDMA) | Stimulant; mild hallucinogen | Emotional elevation, disinhibition | Dehydration, overheating, depressed mood, impaired cognitive and immune functioning |

| LSD | Hallucinogen | Visual “trip” | Risk of panic |

| Marijuana (THC) | Mild hallucinogen | Enhanced sensation, relief of pain, distortion of time, relaxation | Impaired learning and memory, increased risk of psychological disorders, lung damage from smoke |

RETRIEVE IT

“How strange would appear to be this thing that men call pleasure! And how curiously it is related to what is thought to be its opposite, pain! … Wherever the one is found, the other follows up behind.”

Plato, Phaedo, fourth century B.C.E.