26.2 Language Development

26-2 What are the milestones in language development, and how do we acquire language?

Make a quick guess: How many words of your native language(s) did you learn between your first birthday and your high school graduation? Although you use only 150 words for about half of what you say, you probably learned about 60,000 words (Bloom, 2000; McMurray, 2007). That averages (after age 2) to nearly 3500 words each year, or nearly 10 each day! How you did it—how those 3500 words could so far outnumber the roughly 200 words your schoolteachers consciously taught you each year—is one of the great human wonders.

Could you even state the rules of syntax (the correct way to string words together to form sentences) in the language(s) you speak fluently? Most of us cannot. Yet before you were able to add 2 + 2, you were creating your own original and grammatically appropriate sentences. As a preschooler, you comprehended and spoke with a facility that puts to shame college students struggling to learn a new language.

We humans have an astonishing facility for language. With remarkable efficiency, we sample tens of thousands of words in our memory, effortlessly assemble them with near-perfect syntax, and spew them out, three words a second (Vigliocco & Hartsuiker, 2002). Seldom do we form sentences in our minds before speaking them; we organize them on the fly as we speak. And while doing all this, we also adapt our utterances to our social and cultural context. Given how many ways we can mess up, it’s amazing that we master this social dance. When and how does it happen?

When and How Do We Learn Language?

RECEPTIVE LANGUAGE Children’s language development moves from simplicity to complexity. Infants start without language (in fantis means “not speaking”). Yet by 4 months of age, babies can recognize differences in speech sounds (Stager & Werker, 1997). They can also read lips: They prefer to look at a face that matches a sound, so we know they can recognize that ah comes from wide open lips and ee from a mouth with corners pulled back (Kuhl & Meltzoff, 1982). This marks the beginning of the development of babies’ receptive language, their ability to understand what is said to and about them. Infants’ language comprehension greatly outpaces their language production. Even at six months, long before speaking, many infants recognize object names (Bergelson & Swingley, 2012, 2013). At 7 months and beyond, babies grow in their power to do what adults find difficult when listening to an unfamiliar language: to segment spoken sounds into individual words.

babbling stage beginning at about 4 months, the stage of speech development in which the infant spontaneously utters various sounds at first unrelated to the household language.

PRODUCTIVE LANGUAGE Long after the beginnings of receptive language, babies’ productive language, their ability to produce words, matures. Before nurture molds their speech, nature enables a wide range of possible sounds in the babbling stage, beginning around 4 months. Many of these spontaneously uttered sounds are consonant-vowel pairs formed by simply bunching the tongue in the front of the mouth (da-da, na-na, ta-ta) or by opening and closing the lips (ma-ma), both of which babies do naturally for feeding (MacNeilage & Davis, 2000). Babbling does not imitate the adult speech babies hear—it includes sounds from various languages. From this early babbling, a listener could not identify an infant as being, say, French, Korean, or Ethiopian. Deaf infants who observe their deaf parents signing begin to babble more with their hands (Petitto & Marentette, 1991).

Jaimie Duplass/Shutterstock

By about 10 months old, infants’ babbling has changed so that a trained ear can identify the household language (de Boysson-Bardies et al., 1989). Without exposure to other languages, babies lose their ability to discriminate and produce sounds and tones found outside their native language (Meltzoff et al., 2009; Pallier et al., 2001). Thus, by adulthood, those who speak only English cannot discriminate certain sounds in Japanese speech. Nor can Japanese adults with no training in English hear the difference between the English r and l. For a Japanese-speaking adult, la-la-ra-ra may sound like the same syllable repeated.

one-word stage the stage in speech development, from about age 1 to 2, during which a child speaks mostly in single words.

Around their first birthday, most children enter the one-word stage. They have already learned that sounds carry meanings, and if repeatedly trained to associate, say, fish with a picture of a fish, 1-year-olds will look at a fish when a researcher says, “Fish, fish! Look at the fish!” (Schafer, 2005). They now begin to use sounds—usually only one barely recognizable syllable, such as ma or da—to communicate meaning. But family members learn to understand, and gradually the infant’s language conforms more to the family’s language. Across the world, baby’s first words are often nouns that label objects or people (Tardif et al., 2008). At this one-word stage, a single inflected word (“Doggy!”) may communicate a sentence (“Look at the dog out there!”).

two-word stage beginning about age 2, the stage in speech development during which a child speaks mostly in two-word sentences.

telegraphic speech early speech stage in which a child speaks like a telegram—“go car”—using mostly nouns and verbs.

At about 18 months, children’s word learning explodes from about a word per week to a word per day. By their second birthday, most have entered the two-word stage (TABLE 26.1). They start uttering two-word sentences in telegraphic speech. Like today’s texts or yesterday’s telegrams that charged by the word (TERMS ACCEPTED. SEND MONEY), a 2-year-old’s speech contains mostly nouns and verbs (“Want juice”). (Children recognize noun-verb differences—as shown by their responses to a misplaced noun or verb—earlier than they utter sentences with nouns and verbs [Bernal et al., 2010].) Also like telegrams, 2-year-olds’ speech follows the rules of syntax specific to their language. English-speaking children typically place adjectives before nouns—white house rather than house white. Spanish-speaking children reverse this order, as in casa blanca.

Table 9.1: TABLE 26.1

Summary of Language Development

| Month (approximate) |

Stage |

| 4 |

Babbles many speech sounds (“ah-goo”). |

| 10 |

Babbling resembles household language (“ma-ma”). |

| 12 |

One-word stage (“Kitty!”). |

| 24 |

Two-word speech (“Get ball.”). |

| 24+ |

Rapid development into complete sentences. |

Moving out of the two-word stage, children quickly begin uttering longer phrases (Fromkin & Rodman, 1983). If they get a late start on learning a particular language, such as after receiving a cochlear implant or being adopted by a family in another country, their language development still proceeds through the same sequence, although usually at a faster pace (Ertmer et al., 2007; Snedeker et al., 2007). By early elementary school, children understand complex sentences and begin to enjoy the humor conveyed by double meanings: “You never starve in the desert because of all the sand-which-is there.”

Sidney Harris/Science Cartoons Plus

RETRIEVE IT

Question

7RMGRpeCZ8pLAvLcwulRwlHLPAGeCO8QMD9JVXwifFgTUf1U+mv5SK8qIfT5QH32eMt/KQDxsrO9wCaqs/kJnmfPEhoa+1cpaAsNDwrOtK/LaEClLt2/+5eSW0CkYfHOLjR6EXCZpF0XbxN5UQs4I7XhwlNNClRjrgB54ZPjxcrQ+vR+tH3Hsmu+a6QwdHb1VqH8pkvj736qOt6izHS33FncfBk=

ANSWER: Infants normally start developing receptive language skills (ability to understand what is said to and about them) around 4 months of age. Then, starting with babbling at 4 months and beyond, infants normally start building productive language skills (ability to produce sounds and eventually words).

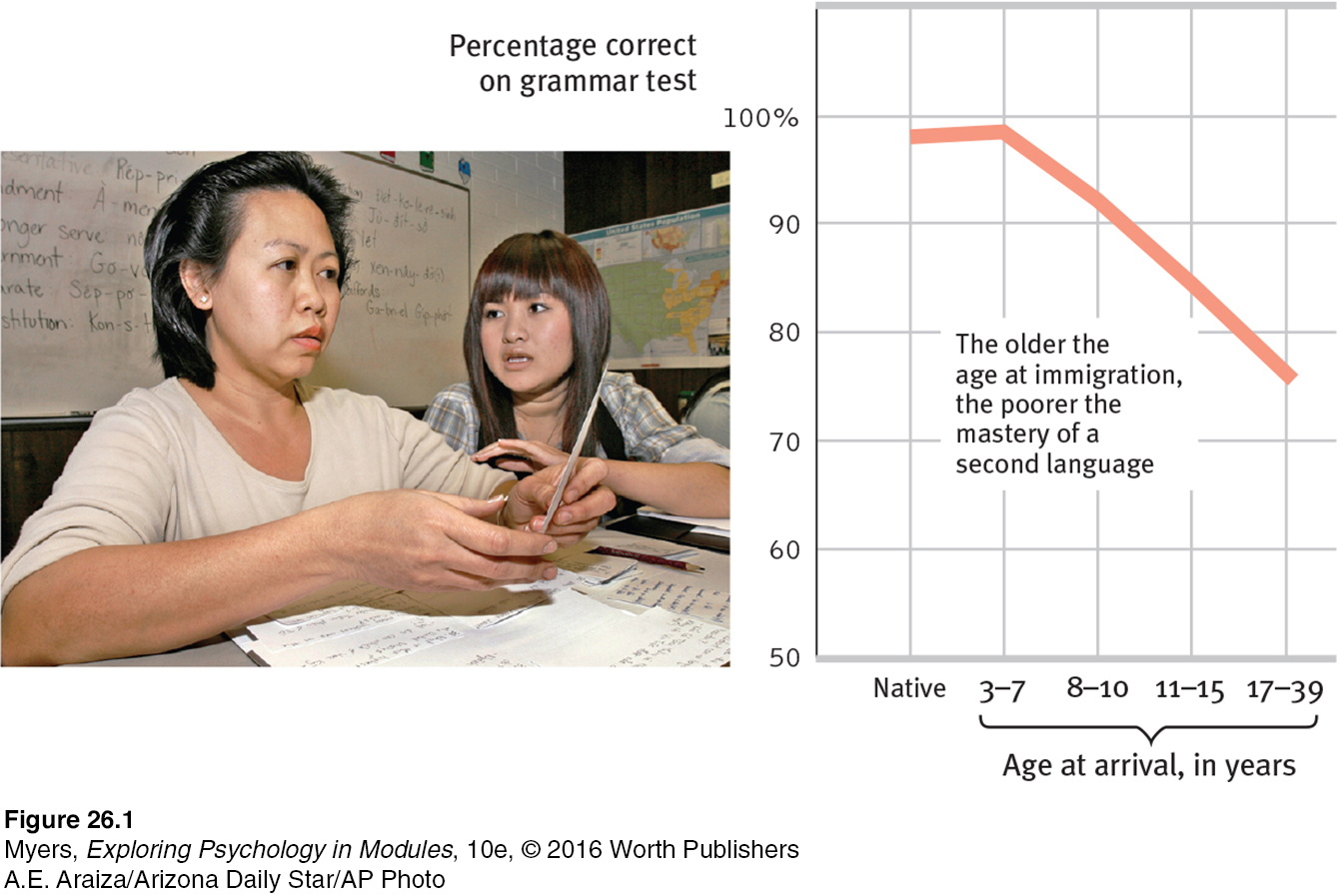

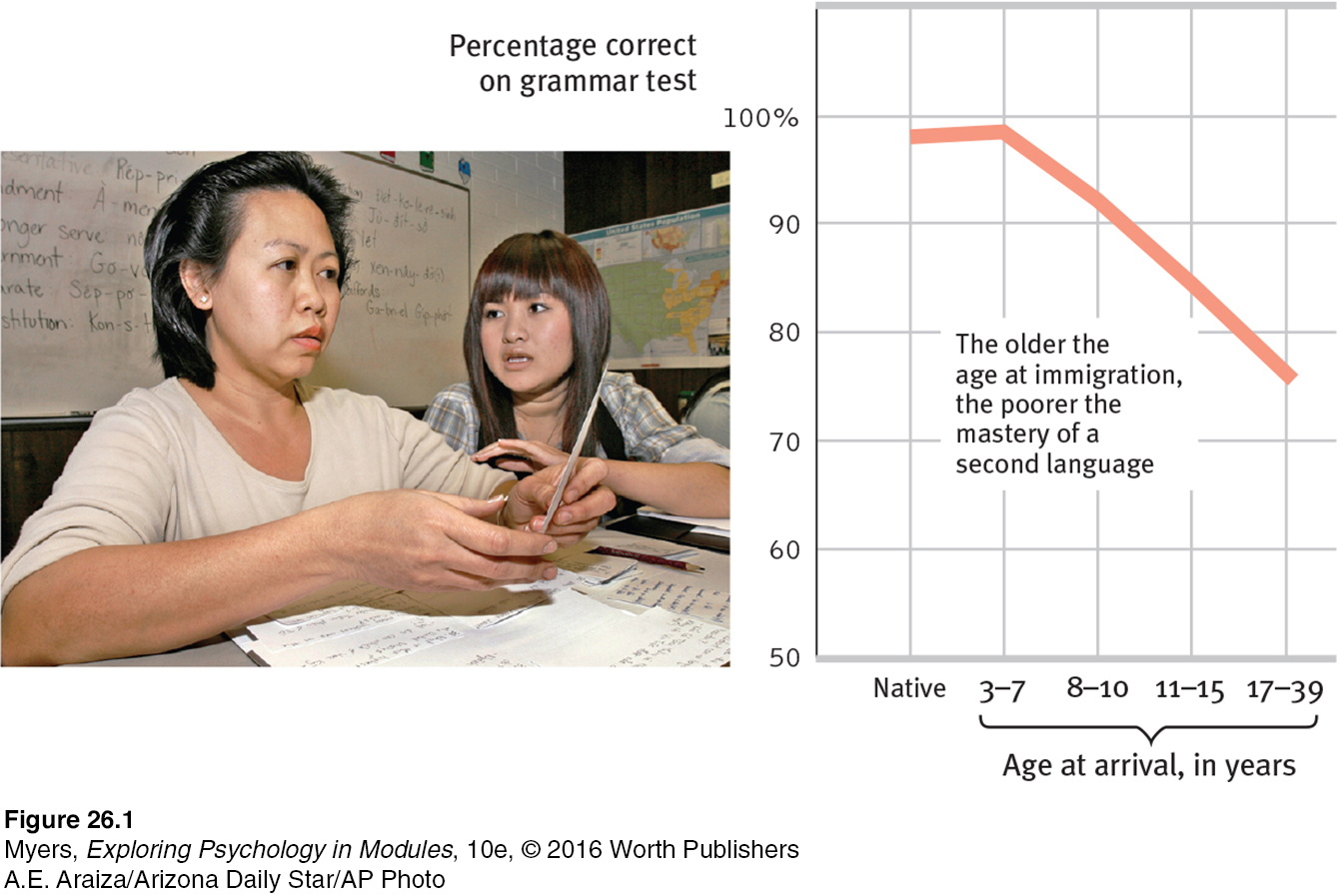

CRITICAL PERIODS Childhood seems to represent a critical (or “sensitive”) period for mastering certain aspects of language before the language-learning window closes (Hernandez & Li, 2007). People who learn a second language as adults usually speak it with the accent of their native language, and they also have difficulty mastering the new grammar. In one experiment, Korean and Chinese immigrants considered 276 English sentences (“Yesterday the hunter shoots a deer”) and decided whether they were grammatically correct or incorrect (Johnson & Newport, 1991). All had been in the United States for approximately 10 years: Some had arrived in early childhood, others as adults. As FIGURE 26.1 reveals, those who learned their second language early learned it best. The older one is when moving to a new country, the harder it will be to learn its language and to absorb its culture (Cheung et al., 2011; Hakuta et al., 2003).

Figure 9.9: FIGURE 26.1 Our ability to learn a new language diminishes with age Ten years after coming to the United States, Asian immigrants took an English grammar test. Although there is no sharply defined critical period for second language learning, those who arrived before age 8 understood American English grammar as well as native speakers did. Those who arrived later did not. (Data from Johnson & Newport, 1991.)

A.E. Araiza/Arizona Daily Star/AP Photo

The window on language learning closes gradually in early childhood. Later-than-usual exposure to language (at age 2 or 3) unleashes the idle language capacity of a child’s brain, producing a rush of language. But by about age 7, those who have not been exposed to either a spoken or a signed language gradually lose their ability to master any language.

“Children can learn multiple languages without an accent and with good grammar, if they are exposed to the language before puberty. But after puberty, it’s very difficult to learn a second language so well. Similarly, when I first went to Japan, I was told not even to bother trying to bow, that there were something like a dozen different bows and I was always going to ‘bow with an accent.’”

Psychologist Stephen M. Kosslyn, “The World in the Brain,” 2008

Deafness and Language Development

Don’t means Don’t—no matter how you say it! Deaf children of deaf-signing parents and hearing children of hearing parents have much in common. They develop language skills at about the same rate, and they are equally effective at opposing parental wishes and demanding their way.

George Ancona

The impact of early experiences is evident in language learning in prelingually (before learning language) deaf children born to hearing-nonsigning parents. These children typically do not experience language during their early years. Natively deaf children who learn sign language after age 9 never learn it as well as those who lose their hearing at age 9 after learning a spoken language such as English. They also never learn English as well as other natively deaf children who learned sign in infancy (Mayberry et al., 2002). Those who learn to sign as teens or adults are like immigrants who learn English after childhood: They can master basic words and learn to order them, but they never become as fluent as native signers in producing and comprehending subtle grammatical differences (Newport, 1990). As a flower’s growth will be stunted without nourishment, so, too, children will typically become linguistically stunted if isolated from language during the critical period for its acquisition.

Hearing improved A boy in Malawi experiences new hearing aids.

Andy Richter/Aurora Photos/Corbis

RETRIEVE IT

Question

s4mP8DWa98lMLVPsHWNxy3pygQR4I3nZdgIY4J6rVgFA0lp+oNpmnvwAoo9oEKtkFaE+UhioSPysn/NmkJN3ZKi13O44Ft8WnBpWdkuH3/4uOdv1

ANSWER: Chomsky maintained that all languages share a universal grammar, and humans are biologically predisposed to learn the grammar rules of language.

Question

yfdsaw5ssVAvbJYpiU7u9aOD1qZqsiroO4CSGwxX71AZLw7tkfVbBjnyzR1R7OTjHIkcOxeqLRALckmUHWiEMw==

ANSWER: Our brain's critical period for language learning is in childhood, when we can absorb language structure almost effortlessly. As we move past that stage in our brain's development, our ability to learn a new language diminishes dramatically.