3 The Market for Foreign Exchange

Exchange rates are set in the foreign exchange (or forex or FX) market. Note the huge volume. Three major trading centers, London, New York, and Tokyo.

1. The Spot Contract

A contract for immediate delivery at the current spot exchange rate. Most trading is done by commercial banks in the major financial centers.

2. Transactions Costs

Market frictions or transaction cost create a spread between buying and selling prices. These costs are low for large firms or banks. We will ignore them.

3. Derivatives

Derivatives are contracts derived from the spot rate. They include forwards, swaps, futures, and options. Except for forwards the derivatives market is fairly small. We will focus on forward contracts.

Day by day, and minute by minute, exchange rates the world over are set in the foreign exchange market (or forex or FX market), which, like any market, is a collection of private individuals, corporations, and some public institutions that buy and sell. When two currencies are traded for each other in a market, the exchange rate is the price at which the trade was done, a price that is determined by market forces.

The forex market is not an organized exchange: each trade is conducted “over the counter” between two parties at numerous interlinked locations around the world. The forex market is massive and has grown dramatically in recent years. According to the Bank for International Settlements, in April 2010 the global forex market traded $4.0 trillion per day in currency, 20% more than 2007, twice as much as in 2004, and almost five times as much as in 1992. The three major foreign exchange centers—the United Kingdom ($1,854 billion per day, almost all in London), the United States ($904 billion, mostly in New York), and Japan ($312 billion, principally in Tokyo)—played home to more than 75% of the trade.7 Other important centers for forex trade include Hong Kong, Singapore, Sydney, and Zurich. Thanks to time-zone differences, when smaller trading centers are included, there is not a moment in the day when foreign exchange is not being traded somewhere in the world. This section briefly examines the basic workings of this market.

The Spot Contract

The simplest forex transaction is a contract for the immediate exchange of one currency for another between two parties. This is known as a spot contract because it happens “on the spot.” Accordingly, the exchange rate for this transaction is often called the spot exchange rate. In this book, the use of the term “exchange rate” always refers to the spot rate. Spot trades are now essentially riskless: technology permits settlement for most trades in real time, so that the risk of one party failing to deliver on its side of the transaction (default risk or settlement risk) is essentially zero.8

Most of our personal transactions in the forex market are small spot transactions via retail channels, but this represents just a tiny fraction of the activity in the forex market each day. The vast majority of trading involves commercial banks in major financial centers around the world. But even there the spot contract is the most common type of trade and appears in almost 90% of all forex transactions, either on its own as a single contract or in trades where it is combined with other forex contracts.

40

Transaction Costs

Give an example of going to the bank to get euros to buy, say, a French book. Imagine the bank quoting a spread that reflects its costs of doing the transaction. But then add that for large institutions these transaction costs are now so low that the spread can be ignored.

When individuals buy a little foreign currency through a retail channel (such as a bank), they pay a higher price than the midrange quote typically seen in the press; and when they sell, they are paid a lower price. The difference or spread between the “buy at” and “sell for” prices may be large, perhaps 2% to 5%. These fees and commissions go to the many middlemen that stand between the person on the street and the forex market. But when a big firm or a bank needs to exchange millions of dollars, the spreads and commissions are very small. Spreads are usually less than 0.1%, and for actively traded major currencies, they are approximately 0.01% to 0.03%.

Spreads are an important example of market frictions or transaction costs. These frictions create a wedge between the price paid by the buyer and the price received by the seller. Although spreads are potentially important for any microeconomic analysis of the forex market, macroeconomic analysis usually proceeds on the assumption that, in today’s world of low-cost trading, the transaction-cost spreads in markets are so low for the key investors that they can be ignored for most purposes.

Derivatives

The spot contract is undoubtedly the most important contract in the forex market, but there are many other related forex contracts. These contracts include forwards, swaps, futures, and options. Collectively, all these related forex contracts are called derivatives because the contracts and their pricing are derived from the spot rate.

With the exception of forwards, the forex derivatives market is small relative to the entire global forex market. According to the most recent April 2010 survey data from the Bank for International Settlements, the trade in spot contracts amounted to $1,490 billion per day (37% of trades), the trade in forward contracts was $475 billion per day (12% of trades), and the trade in swaps (which combine a spot and a forward) accounted for $1,765 billion per day (44% of trades). The remaining derivative trades amounted to $250 billion per day (7% of trades).

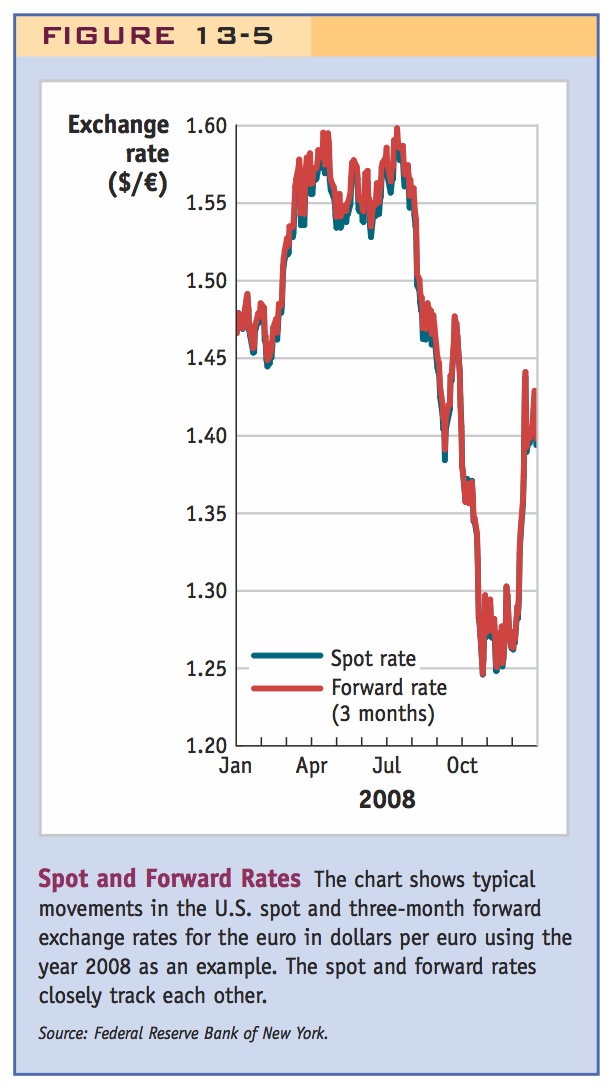

For the rest of this chapter, we focus on the two most important contracts—the spot and the forward. Figure 13-5 shows recent trends in the spot and forward rates in the dollar–euro market. The forward rate tends to track the spot rate fairly closely, and we will explore this relationship further in a moment.

This is certainly true, but students are interested in what these things are. So follow the following material to talk briefly about option contracts and how they permit hedging and speculation, and about how swaps relate to forwards.

The full study of derivative markets requires an in-depth analysis of risk that is beyond the scope of this book. Such topics are reserved for advanced courses in finance that explore derivative contracts in great detail. The following application, however, will provide you with a basic guide to derivatives.

41

You might ask students to think about what kinds of traders would use futures rather than forwards.

Futures are also marked to market, so that profits and losses are closed at the end of the trading day.

Brief descriptions of forwards, swaps, futures, and options, contracts that allow traders to hedge (avoid risk) or speculate (accept risk).

Foreign Exchange Derivatives

There are many derivative contracts in the forex market, of which the following are the most common.

Forwards A forward contract differs from a spot contract in that the two parties make the contract today, but the settlement date for the delivery of the currencies is in the future, or forward. The time to delivery, or maturity, varies—30 days, 90 days, six months, a year, or even longer—depending on the contract. However, because the price is fixed as of today, the contract carries no risk.

Swaps A swap contract combines a spot sale of foreign currency with a forward repurchase of the same currency. This is a common contract for counterparties dealing in the same currency pair over and over again. Combining two transactions reduces transactions costs because the broker’s fees and commissions are lower than on a spot and forward purchased separately.

Futures A futures contract is a promise that the two parties holding the contract will deliver currencies to each other at some future date at a prespecified exchange rate, just like a forward contract. Unlike the forward contract, however, futures contracts are standardized, mature at certain regular dates, and can be traded on an organized futures exchange. Hence, the futures contract does not require that the parties involved at the delivery date be the same two parties that originally made the deal.

Options An option contract provides one party, the buyer, with the right to buy (call) or sell (put) a currency in exchange for another at a prespecified exchange rate at a future date. The other party, the seller, must perform the trade if asked to do so by the buyer, but a buyer is under no obligation to trade and, in particular, will not exercise the option if the spot price on the expiration date turns out to be more favorable.

All of these products exist to allow investors to trade foreign currency for delivery at different times or with different contingencies. Thus, derivatives allow investors to engage in hedging (risk avoidance) and speculation (risk taking).

- Example 1: Hedging. As chief financial officer of a U.S. firm, you expect to receive payment of €1 million in 90 days for exports to France. The current spot rate is $1.20 per euro. Your firm will incur losses on the deal if the euro weakens (dollar strengthens) to less than $1.10 per euro. You advise the firm to buy €1 million in call options on dollars at a rate of $1.15 per euro, ensuring that the firm’s euro receipts will sell for at least this rate. This locks in a minimal profit even if the spot exchange rate falls below $1.15 per euro. This is hedging.

- Example 2: Speculation. The market currently prices one-year euro futures at $1.30 per euro, but you think the euro will strengthen (the dollar will weaken) to $1.43 per euro in the next 12 months. If you wish to make a bet, you would buy these futures, and if you are proved right, you will realize a 10% profit. In fact, any spot rate above $1.30 per euro will generate some profit. If the spot rate is at or below $1.30 per euro a year from now, however, your investment in futures will generate a loss. This is speculation.

42

Private Actors

4. Private Actors

Most traders work for banks. They buy and sell FX for customers who want to buy or sell goods, services, and assets in other countries and to make profit for themselves. Most of the volume involves interbank trading, which is highly concentrated in 10 banks. Some corporations and nonbank financial institutions are also active in the market.

The key actors in the forex market are the traders. Most forex traders work for commercial banks. These banks trade for themselves in search of profit and also serve clients who want to import or export goods, services, or assets. Such transactions usually involve a change of currency, and commercial banks are the principal financial intermediaries that provide this service.

For example, suppose Apple Computer Inc. has sold €1 million worth of computers to a German distributor and wishes to receive payment for them in U.S. dollars (with the spot rate at $1.30 per euro). The German distributor informs its commercial bank, Deutsche Bank, which then debits €1 million from the distributor’s bank account. Deutsche Bank then sells the €1 million bank deposit in the forex market in exchange for a $1.3 million deposit and credits that $1.3 million to Apple’s bank in the United States, which, in turn, deposits $1.3 million into Apple’s account.

This is an important fact to note.

This is an example of interbank trading. This business is highly concentrated: about 75% of all forex market transactions globally are handled by just 10 banks, led by names such as Deutsche Bank, UBS, Citigroup, HSBC, and Barclays. The vast majority of forex transactions are profit-driven interbank trades, and it is the exchange rates for these trades that underlie quoted market exchange rates. Consequently, we focus on profit-driven trading as the key force in the forex market that affects the determination of the spot exchange rate.

Other actors are increasingly participating directly in the forex market. Some corporations may trade in the market if they are engaged in extensive transactions either to buy inputs or sell products in foreign markets. It may be costly for them to do this, but by doing so, they can bypass the fees and commissions charged by commercial banks. Similarly, some nonbank financial institutions such as mutual fund companies may invest so much overseas that they can justify setting up their own forex trading operations.

Government Actions

5. Government Actions

Governments can influence the FX market in two ways: (1) They can impose capital controls to restrict cross-border financial transactions. Examples include Malaysia, China, Argentina, Iceland, and Cyprus. (2) They can intervene in the market by buying or selling FX reserves to achieve a desired peg. There are two problems with FX intervention: (1) the resource cost of holding the reserve, and (2) reserves can run out, precipitating a currency crisis.

We have so far described the forex market in terms of the private actors. Our discussion of the forex market is incomplete, however, without mention of actions taken by government authorities. Such activities are by no means present in every market at all times, but they are sufficiently frequent that we need to fully understand them. In essence, there are two primary types of actions taken by governments in the forex market.

At one extreme, it is possible for a government to try to completely control the market by preventing its free operation, by restricting trading or movement of forex, or by allowing the trading of forex only through government channels. Policies of this kind are a form of capital control, a restriction on cross-border financial transactions. In the wake of the 1997 Asian exchange rate crisis, for example, the Malaysian government temporarily imposed capital controls, an event that prompted Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad to declare that “currency trading is unnecessary, unproductive and totally immoral. It should be stopped, it should be made illegal.”9 In more recent years, capital controls have been seen in countries such as China, Argentina, Iceland, and Cyprus.

43

Capital controls are never 100% successful, however. Illegal trades will inevitably occur and are almost impossible to stop. The government may set up an official market for foreign exchange and issue a law requiring people to buy and sell in that market at officially set rates. But illicit dealings can persist “on the street” in black markets or parallel markets where individuals may trade at exchange rates determined by market forces and not set by the government. For example, in Italy in the 1930s, the Mussolini regime set harsh punishments for trading in foreign currency that gradually rose to include the death penalty, but trading still continued on the black market.

A less drastic action taken by government authorities is to let the private market for forex function but to fix or control forex prices in the market through intervention, a job typically given to a nation’s central bank.

Comparing a pegged rate to a price control on grain is the single best way to explain what a pegged rate is. One might even consider drawing demand and supply curves to foreign exchange (although that requires some motivation) to show how pegging below the market rate requires a depletion of reserves. This in turn permits a graphic depiction of how this could engender speculation that would precipitate a crisis.

How do central banks intervene in the forex market? Indeed, how can a government control a price in any market? This is an age-old problem. Consider the issue of food supply in medieval and premodern Europe, one of the earliest examples of government intervention to fix prices in markets. Rulers faced a problem because droughts and harvest failures often led to food shortages, even famines—and sometimes political unrest. Governments reacted by establishing state-run granaries, where wheat would be stored up in years of plenty and then released to the market in years of scarcity. The price could even be fixed if the government stood ready to buy or sell grain at a preset price and if the government always had enough grain in reserve to do so. Some authorities successfully followed this strategy for many years. Others failed when they ran out of grain reserves. Once a reserve is gone, market forces take over. If there is a heavy demand that is no longer being met by the state, a rapid price increase will inevitably follow.

Government intervention in the forex market works in a similar manner. To maintain a fixed or pegged exchange rate, the central bank must stand ready to buy or sell its own currency, in exchange for the base foreign currency to which it pegs, at a fixed price. In practice, this means keeping some foreign currency reserves as a buffer, but having this buffer raises many problems. For one thing, it is costly—resources are tied up in foreign currency when they could be invested in more profitable activities. Second, these reserves are not an unlimited buffer, and if they run out, then market forces will take over and determine the exchange rate. In later chapters, we explore why countries peg, how a peg is maintained, and under what circumstances pegs fail, leading to an exchange rate crisis.

So, as we’ve seen, the extent of government intervention can vary. However, even with complete capital controls, including the suppression of the black market, private actors are always present in the market. Our first task is therefore to understand how private economic motives and actions affect the forex market.