1 Facts About Exchange Rate Crises

1. What Is an Exchange Rate Crisis?

A depreciation of 10 or 15 percent is “large” for developed economies; 20 to 25 percent for developing economies. Crises may occur in either developed or developing economies, but the depreciations in the crises are usually larger for developing economies.

2. How Costly Are Exchange Rate Crises?

Economic costs: Advanced economies bounce back within two or three years after the crisis; developing economies don’t recover, but suffer substantially lower growth rates for three or four years. There is usually a major recession that has severe social, financial, and political consequences.

a. Causes: Other Economic Crises

Exchange rate crises are often linked to banking or financial crises, or sovereign debt defaults, that disrupt credit flows within and to the economy. When they occur together, they are called “twin” or even “triple” crises.

To understand the importance of exchange rate crises, let’s examine what crises look like and the costs associated with them.

What Is an Exchange Rate Crisis?

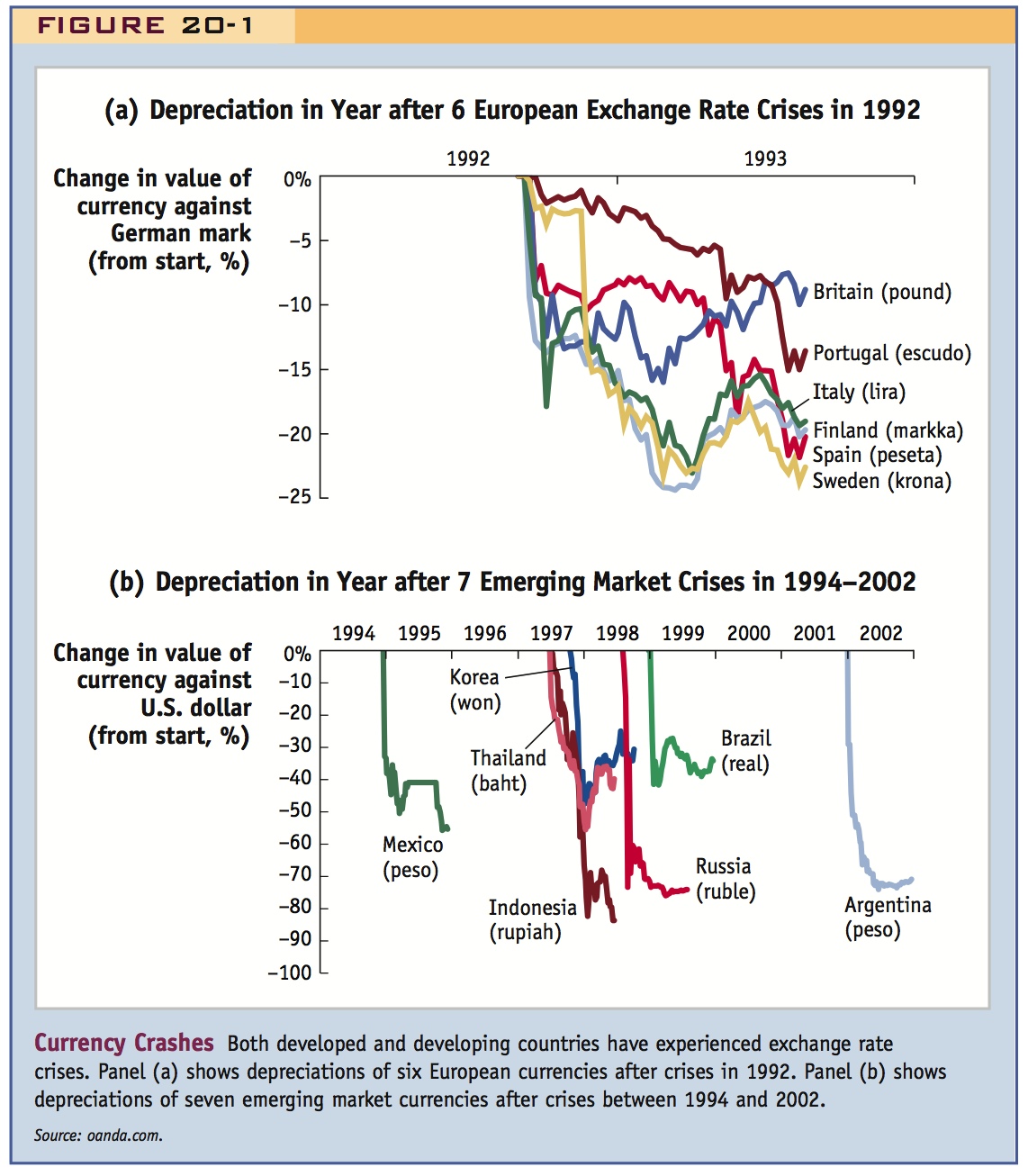

A simple definition of an exchange rate crisis would be a “big” depreciation that occurs after a peg breaks.2 But how big is big enough to qualify as a crisis? In practice, in an advanced country, a 10% to 15% depreciation might be considered large. In emerging markets, the bar might be set higher, say, 20% to 25%.3 Examples of such crises are shown in Figure 20-1.

Panel (a) shows the depreciation of six European currencies against the German mark after 1992. Four currencies (the escudo, lira, peseta, and pound) were part of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM); the other two (the markka and krona) were not in the ERM but were pegging to the German mark. All six currencies lost 15% to 25% of their value against the mark within a year.

Panel (b) shows the depreciation of seven emerging market currencies against the U.S. dollar in various crises that occurred from 1994 to 2002. These depreciations, while also very rapid, were much larger than those in panel (a). These currencies lost 50% to 75% of their value against the dollar in the year following the crisis.

The figure illustrates two important points. First, exchange rate crises can occur in advanced countries as well as in emerging markets and developing countries. Second, the magnitude of the crisis, as measured by the subsequent depreciation of the currency, is often much greater in emerging markets and developing countries.

How Costly Are Exchange Rate Crises?

There is much evidence on the potentially damaging effects of exchange rate crises. The economic costs are often large, and the political costs can be even more dramatic (see Side Bar: The Political Costs of Crises).

349

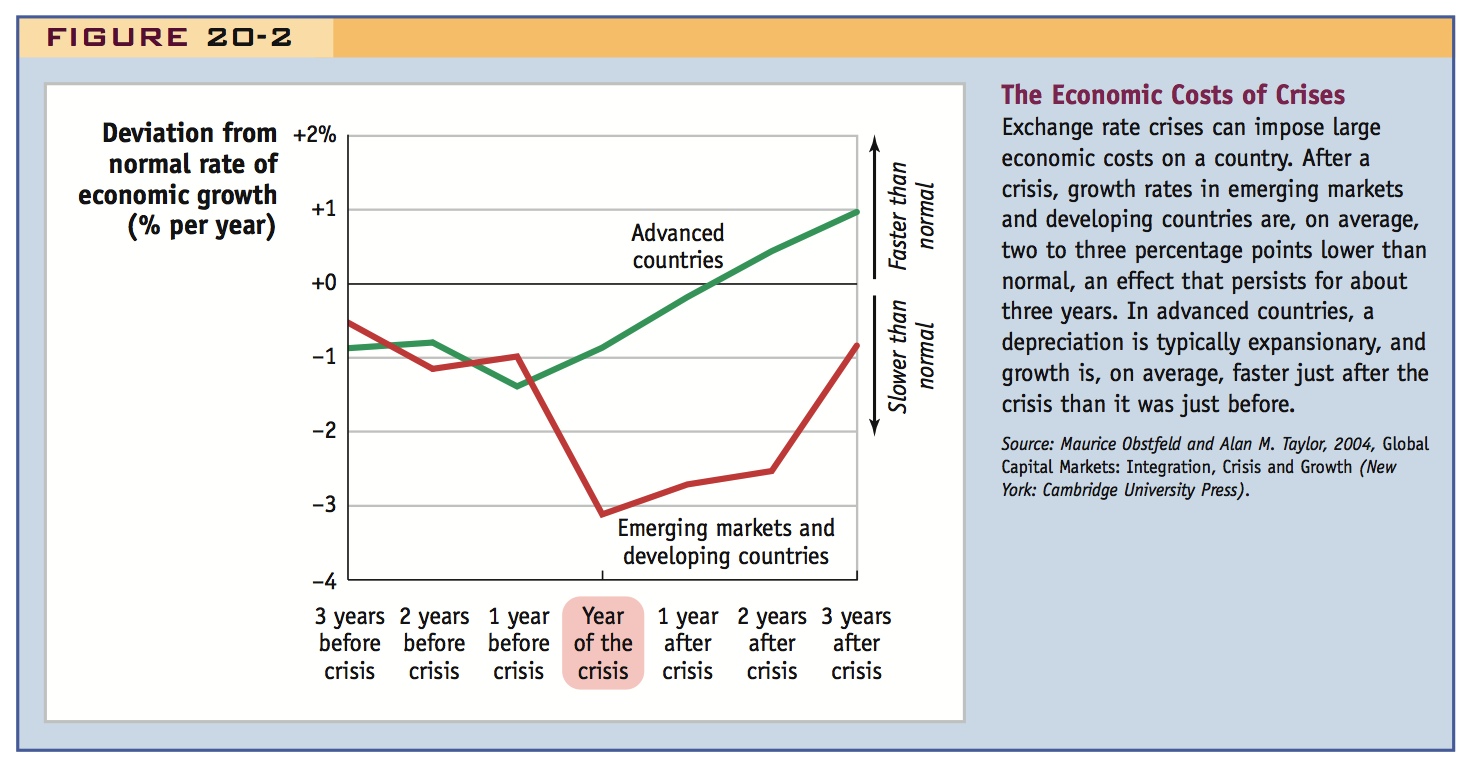

Figure 20-2 presents some evidence on the effects of exchange rate crises. Annual rates of growth of GDP in years close to crises were compared with growth in other (i.e., “normal”) years to obtain a measure of how growth differs during crisis periods. The figure shows that just before a crisis all countries have economic growth that is between 0.5% and 1.0% below that in normal years.

After a typical exchange rate crisis, advanced countries and emerging markets react differently. Advanced countries tend to bounce back: growth accelerates and is above normal by the second and third years after the crisis. Emerging markets do not bounce back, and growth usually plummets: it is 2.5% to 3% below normal in the year of the crisis and the two subsequent years, and is still 1% below normal in the third year. All those reductions in growth add up to about a 10% decline in GDP relative to its typical trend three years after the crisis—a major recession.4

350

The major downturns in emerging markets often have serious economic and social consequences. For example, in the aftermath of the Argentina crisis of 2001 to 2002, news reports were filled with shocking tales of unemployment, financial ruin, rising poverty, hunger, and deprivation. After the Asian crisis of 1997, the recoveries were a little faster, but the economic misfortunes were still deep and painful.

This chapter develops first- and second-generation models of currency crises. Note in passing that the link between currency and banking crises is so strong that there is a third generation of models that has developed to understand it.

Causes: Other Economic Crises Why are exchange rate crises sometimes so damaging? From the crises of the 1990s, economists learned that exchange rate crises usually go hand in hand with other types of economically harmful financial crises, especially in emerging markets. In the private sector, if banks and other financial institutions face adverse shocks, they may become insolvent, causing them to close or declare bankruptcy: this is known as a banking crisis. In the public sector, if the government faces adverse shocks, it may default and be unable or unwilling to pay the principal or interest on its debts: this is known as a sovereign debt crisis or default crisis. Both banking and default crises can have damaging effects on the economy because they disrupt the flow of credit within and between countries. (In a later chapter, we examine default crises in more detail, including their links to banking and exchange rate crises.)

351

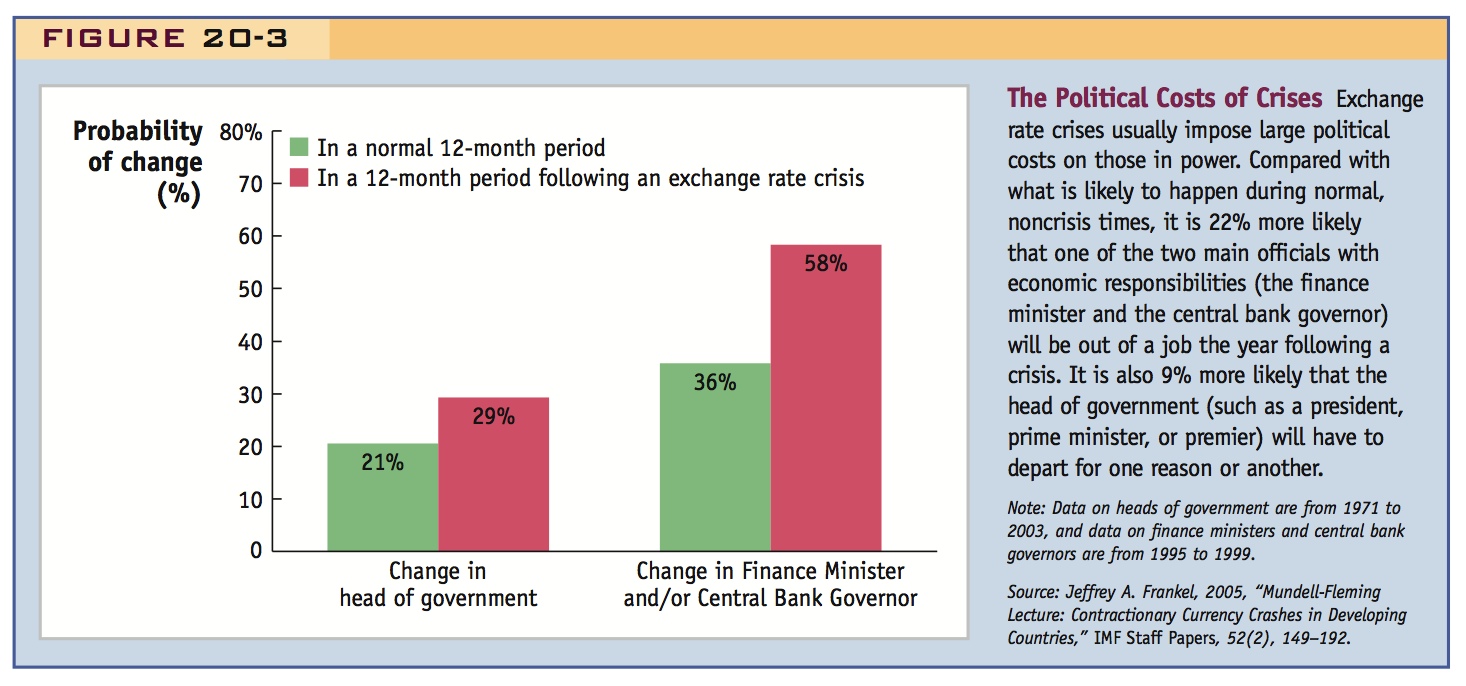

Crises often are followed by personnel changes in the central bank or finance ministries, and sometimes in a country’s leadership.

3. Summary

Exchange rate crises are common and have disastrous consequences. Why are fixed rate regimes so fragile? Why and how do crises occur? How can their costs be reduced?

The Political Costs of Crises

Exchange rate crises don’t simply have economic consequences—they often have political consequences, too. Figure 20-3 shows that exchange rate crises are often followed by personnel changes at the central bank or finance ministry and not infrequently by a change in a country’s leadership as well.

At first, this result might seem odd. As the economist Jeffrey Frankel said, speaking of the Indonesian crisis of 1997: “What is it about devaluation that carries such big political costs? How is it that a strong ruler like Indonesia’s Suharto can easily weather 32 years of political, military, ethnic, and environmental challenges, only to succumb to a currency crisis?”*

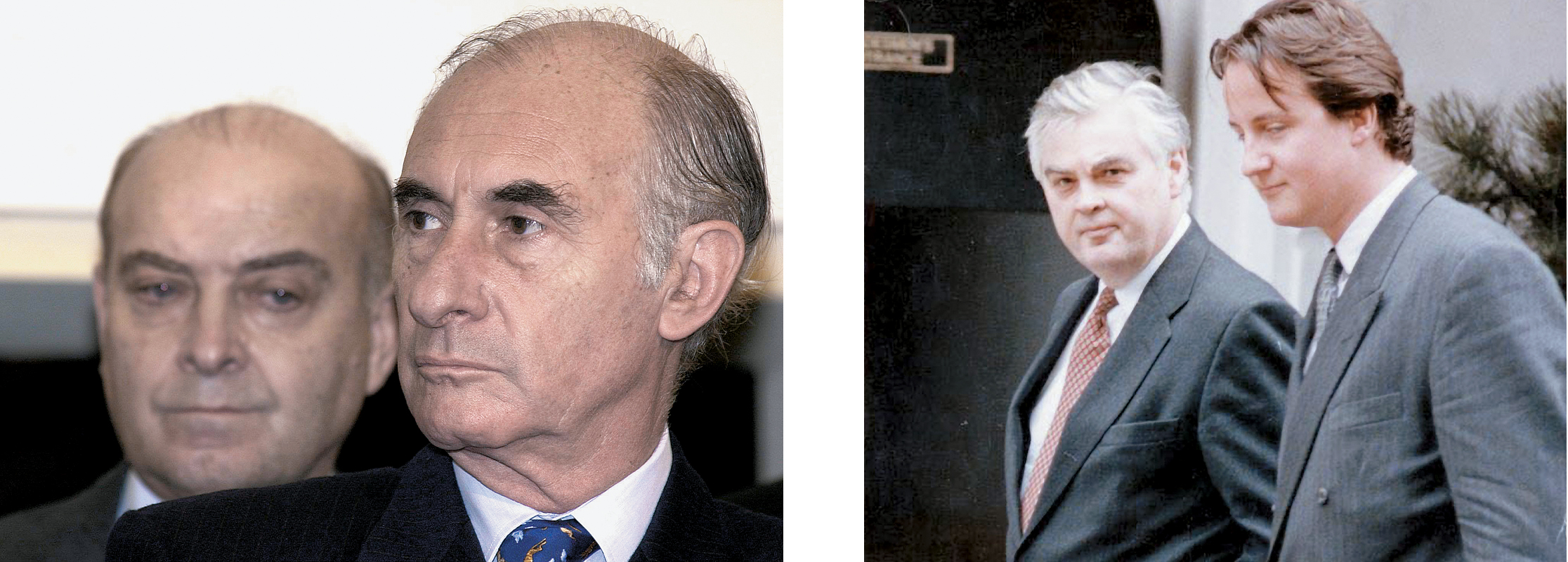

In emerging markets, we know that the economic costs of exchange rate crises can be large, which helps explain how a Suharto could be undermined. There are many other examples: the Radical Party is the oldest political party in Argentina, but after the exchange rate crisis in 2001 to 2002 under the leadership of President Fernando de la Rúa and Economy Minister Domingo Cavallo, the party faced extinction, polling just 2.3% in the 2003 presidential election.†

Still, why do exchange rate crises carry large political costs in advanced countries where the exit from an exchange rate peg often allows for a depreciation and favorable growth performance? A pertinent example is the decision by Britain’s Conservative government to exit the ERM on “Black Wednesday,” September 16, 1992. Chancellor Norman Lamont left his job within a year, and Prime Minister John Major tasted defeat at the next general election in 1997, despite faster economic growth after 1992.

Solo Syndication/Zuma Press

The legacy of “Black Wednesday” haunted the Conservatives for years. On the question of economic competence, the polls gave the subsequent Labour government a massive lead for many years. It was not until 2010 that the Conservatives regained power, but only in a coalition, and under their fifth leader in 13 years, David Cameron (who had been a junior minister working under Lamont at the Treasury on that fateful day in 1992).

Even when a depreciation turns out to be good for the economy, the collapse of a peg typically destroys the reputations of politicians and policy makers for credibility and competence. Regaining the trust of the people can take a very long time.

* Jeffrey A. Frankel, “Mundell-Fleming Lecture: Contractionary Currency Crashes in Developing Countries,” IMF Staff Papers, 52(2), 149–192.

†Cavallo had previously served the rival Peronist Party as economy minister in the Menem administration and had presided over the creation of the fixed exchange rate regime, as well as its collapse.

352

International macroeconomists thus have three crisis types to consider: exchange rate crises, banking crises, and default crises. Evidence shows they can occur one at a time, but they are quite likely to occur simultaneously:

- The likelihood of a banking or default crisis increases significantly when a country is having an exchange rate crisis. One study found that the probability of a banking crisis was 1.6 times higher during an exchange rate crisis (16% versus 10% on average). Another study found that the probability of a default crisis was more than 3 times higher during an exchange rate crisis (39% versus 12% on average).5 Explanations for these findings focus on valuation effects. As we saw in the last chapter, a big depreciation causes a sudden increase in the local currency value of dollar debts (principal and interest). Because this change in value can raise debt burdens to intolerable levels, exchange rate crises are frequently accompanied by financial distress in the private and public sectors.

- The likelihood of an exchange rate crisis increases significantly when a country is having a banking or default crisis. The same two studies just noted found that the probability of an exchange rate crisis was 1.5 times higher during a banking crisis (46% versus 29% on average). The probability of an exchange rate crisis was more than 5 times higher during a default crisis (84% versus 17% on average).

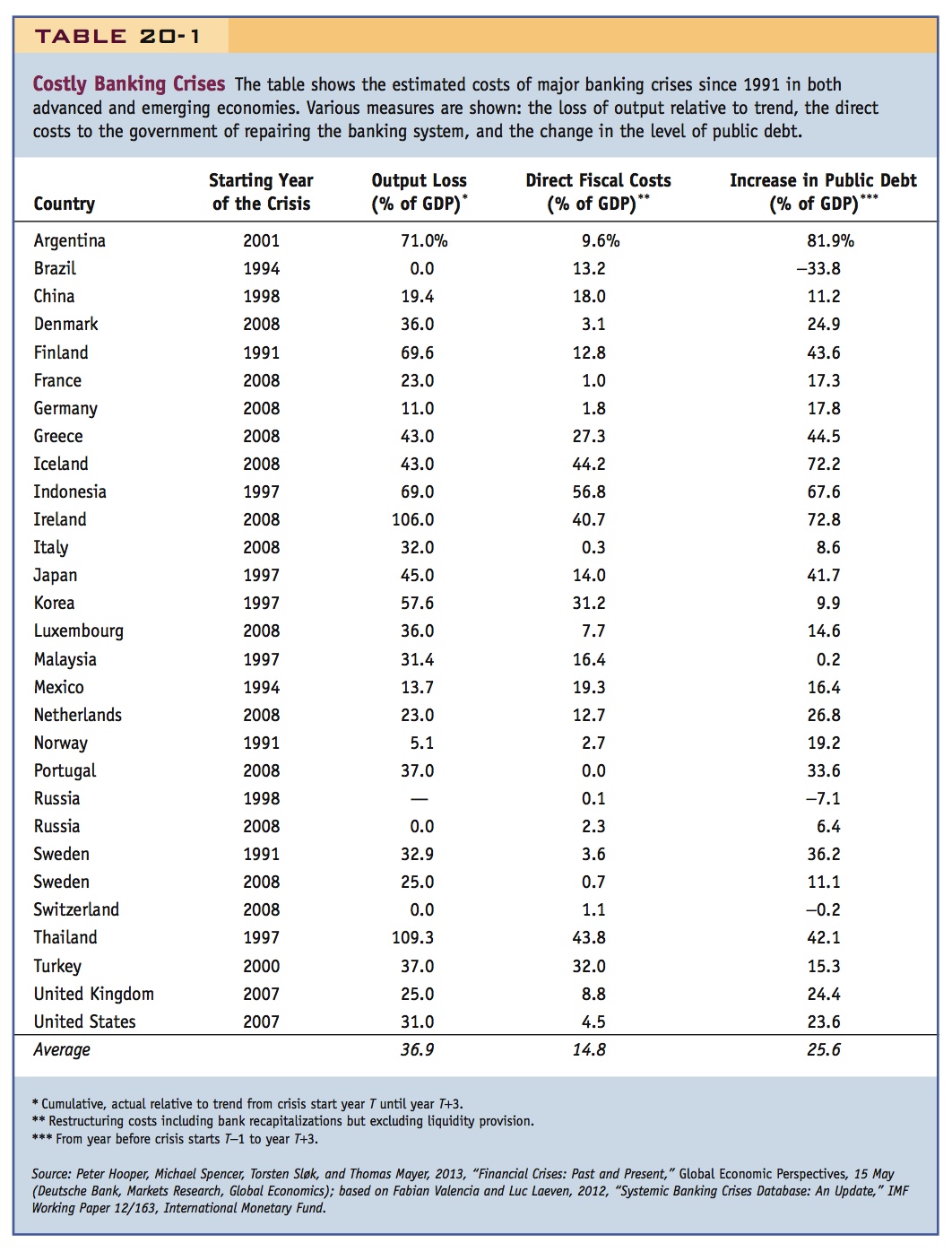

Explanations for these reverse effects center on the issuance of money by the central bank to bail out banks and governments. Banking crises can be horrendously costly. As can be seen in Table 20-1, countries have to cope not only with direct fiscal costs of fixing a damaged banking sector (e.g., through the bailout and recapitalization of insolvent institutions) but also with typically very long and protracted recessions where output is significantly below trend. These slumps in turn create added cyclical drag on the government’s fiscal position (lower taxes, higher spending) leading to a large run up in public debt. Such burdens might be handled purely via future fiscal adjustments, but they can sometimes endanger monetary policy and the nominal anchor. If a country is having a banking crisis, the central bank will be under pressure to extend credit or outright transfers to weak banks to prop them up. If a country is having a default crisis, the government will lose access to foreign and domestic loans and may pressure the central bank to lend to the government. This raises a key question: Why does the extension of credit by the central bank threaten an exchange rate peg? In this chapter, we show how a peg works—and how, if the central bank issues too much money to pay for bailouts and/or government deficits, it can place the peg at risk by causing a loss of reserves.

These findings show how crises are likely to happen in pairs, known as twin crises, or all three at once, known as triple crises, magnifying the costs of any one type of crisis.

Summary

Exchange rate crises have been recurring for more than 100 years, and we have not seen the last of them. They can generate significant economic costs, and policy makers and scholars are seriously concerned about how to prevent them. What is it about fixed exchange rate regimes that makes them so fragile? Why and how do crises happen? And how can the risks of such crises be mitigated? These are the questions we address in the rest of this chapter.

353

354