Chapter 18 HEADLINES: Poland Is Not Latvia

See the full-size image.

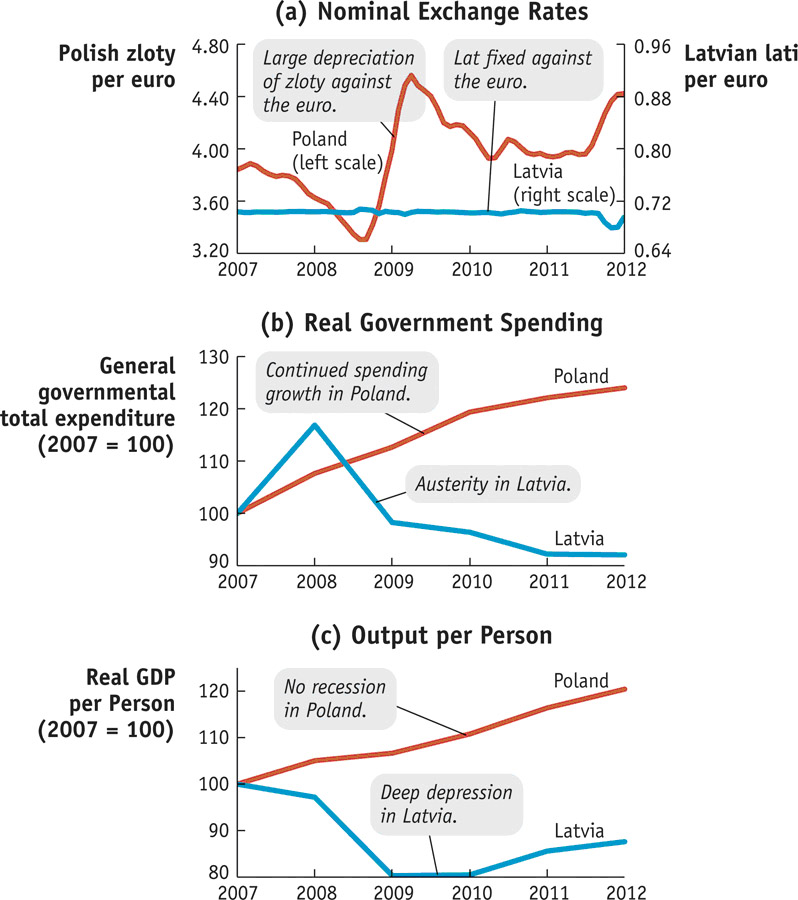

Eastern Europe faced difficult times in the Great Recession. Yet not all countries suffered the same fate, as we see from this story, and the macroeconomic data presented and discussed in Figure 18-

…Poland and Latvia … inherited woefully deficient institutions from communism and have struggled with many of the same economic ills over the past two decades. They have also adopted staggeringly different approaches to the crisis, one of which was a lot more effective than the other.

…I don’t think it’s being radical to say that [since 2004] Poland’s performance is both a lot better and a lot less variable and that if you were going to draw lessons from one of the two countries that it should probably be the country which avoided an enormous bubble and subsequent collapse. What is it that caused Poland’s economy to be so sound? Was it austerity? Was it hard money?

…Both Latvia and Poland actually ran rather substantial budget deficits during the height of the crisis, though Latvia’s budgeting in the years preceding the crisis was more balanced and restrained than Poland’s… . Poland’s government spending as a percentage of GDP was also noticeably higher than Latvia’s both before the crisis and after it… . You can see how, starting in 2008, Latvia starts to make some sharp cuts while Poland continues its steady, modest increases.

So, basically, Poland is a country whose government habitually ran budget deficits before, during, and after the crisis, whose government spends a greater percentage of GDP than Latvia, and which did not cut spending in response to the crisis. Latvia,in contrast, ran balanced budgets, had a very small government as a percentage of GDP, and savagely cut spending in response to the crisis. While I don’t think you can call Poland “profligate,” if economics really were a morality play you’d expect the Latvians to come out way ahead since they’ve followed the austerity playbook down to the letter. However, in the real world, Poland’s economic performance has been vastly, almost comically, superior to Latvia’s despite the fact that the country didn’t make any “hard choices.”

All of this, of course, leaves out monetary policy… . Part of the reason that Latvia’s economic performance has been so awful is that it has pegged its currency to the Euro, a course of action which has made the Lat artificially expensive and which made Latvia’s course of “internal devaluation” necessary… . Poland did the exact opposite, allowing its currency, the zloty, to depreciate massively against the Euro…

Poland did not, in other words, “defend the zloty” because it realized that a devaluation of its currency would be incredibly helpful. And the Polish economy has continued to churn along while most of its neighbors have either crashed and burned or simply stagnated… .

There are plenty of lessons from Poland’s economic success, including the need for effective government regulation (Poland never had an out-

Source: Excerpted from Mark Adomanis, “If Austerity Is So Awesome Why Hasn’t Poland Tried It?” forbes.com, January 10, 2013. Reproduced with Permission of Forbes Media LLC © 2013.

Questions to Consider

After reading Poland Is Not Latvia, consider the question(s) below. Then “submit” your response.

Question

VXT7/LsOccOoDsJvZoJFDGtEOjXI4OTGrsJzKK3yDWMjGS2+3qqLwMtzmgL/2CPVHIW1WSHXgqXbdwsNurmhYqXfcBoG5fOqn2WJqWyKFhKEv+Tfff3ud2+CckXXJjQLhkccpJrJ3rjxi0rFQuestion

keyI1vJTofK0Dqg9pF6sj5+GO+Av3FmKQkhqKHCT0Av2Tgi/5UCfUCDD1czHYuy57Lc2PBxZG6whBkY9I2lpGm92EeA611VJ3VOgwKyJ41ksMOZOkA1ZfUlbEzH9ntd+QbaRL43CGjOc51tHp2lwP2IZ1ygV1Xztpj9edtTHiZ/eXFM1ssl7cqsl6mnkcAlrizIv78phxwM1XwHoxC2wtI9BGh63mQnJ2Yc0jO1XEGaQJaT+MipNPcnILDwmMD8OiUH3WMEZBLWHgngddCSdnrd4ThF7Ntz2isJ2cSgRZveEsmA0MWmQmYVp0VQBwmX/ihLlWPmD+6etDDLXG4+XD440sUthDD+QzzFeQUTHlZ72EDytsDDcoGGlret9EA5GmpsTiEfdMbU7r4MS62QinGfg1g1GrvKxmqXVBa/7kNDpJ29aeRAxo14ToZcfJGZGQ0XPZKeUv96J+MJZJdw40Ux/gXOz/pzY+28qiKpIDrOAlGRjaH3wASlbNWKBZQeG/r6QC9ZnozErymeWTYynuA8s5kQg/epn3+pJCsoxyOw56xTQF3MGqSM3pcv41XLxtSaTxG0Wn0KU1A4ZUBDB2wHfebODDPAiUwpwXA==Question

rIxdUPJ/rUeuTQ1pSygrA9of9sc2amKCmPcAO1YS2JP4B+XVWGd+NwgkEq5h9U7N9n2xY4FLfVz/XREKD8IN/BWurzfUMaUZTWdO/wbD4SdWzIOlolcpiJql/cKDxcX+s5eMOBGmVE10W74EHLoEznzn/wCxxoDRAOnlexzUu9WbBPgv2GGWJUOkzntqqG2tEdOP5eUf/M1AaD+/O/Ug5l+6ZyG4ODqPqz8mN2WULFioibnmrVb2Cbo1m4GMnQbxP2gq9p3twVTvqIKYvq8LnC55wSmQKs8o3cvJe7mPDLFsHkv1/uUhhRGGp90GjOW+JsGAQg==

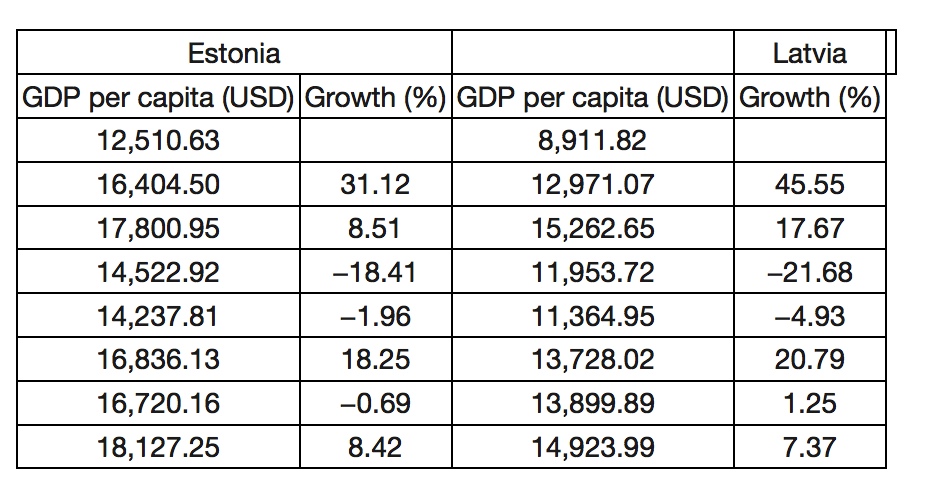

Estonia has a fixed exchange rate with the EMU and actually joined the monetary union in 2011. They also decided to follow a path of austerity during the Great Recession. It would be expected then that the economic outcomes of these policy choices are the same.