2 Export Subsidies in a Small Home Country

Start with a small country and then move to a large one: Small country faces a world price of a good above its autarky price, so in free trade equilibrium it is an exporter.

1. Impact of an Export Subsidy

A per-unit export subsidy raises the domestic price. Quantity demanded falls and quantity supplied increases, so exports increase. Since the subsidy is like a negative tariff, the Home export supply curve shifts down. The Foreign import demand curve is flat because the country is a price taker.

a. Summary

Price and quantity both increase. Exports increase, and the subsidy drives a wedge between the price that exporters receive and what Foreign importers pay.

b. Impact of the Subsidy on Home Welfare

Consumer surplus falls, producer surplus increases, and the government suffers a loss in revenue. There are efficiency losses in both production and consumption.

To see the effect of export subsidies on prices, exports, and welfare, we begin with a small Home country that faces a fixed world price for its exports. Following that, we see how the outcomes differ when the Home country is large enough to affect world prices.

332

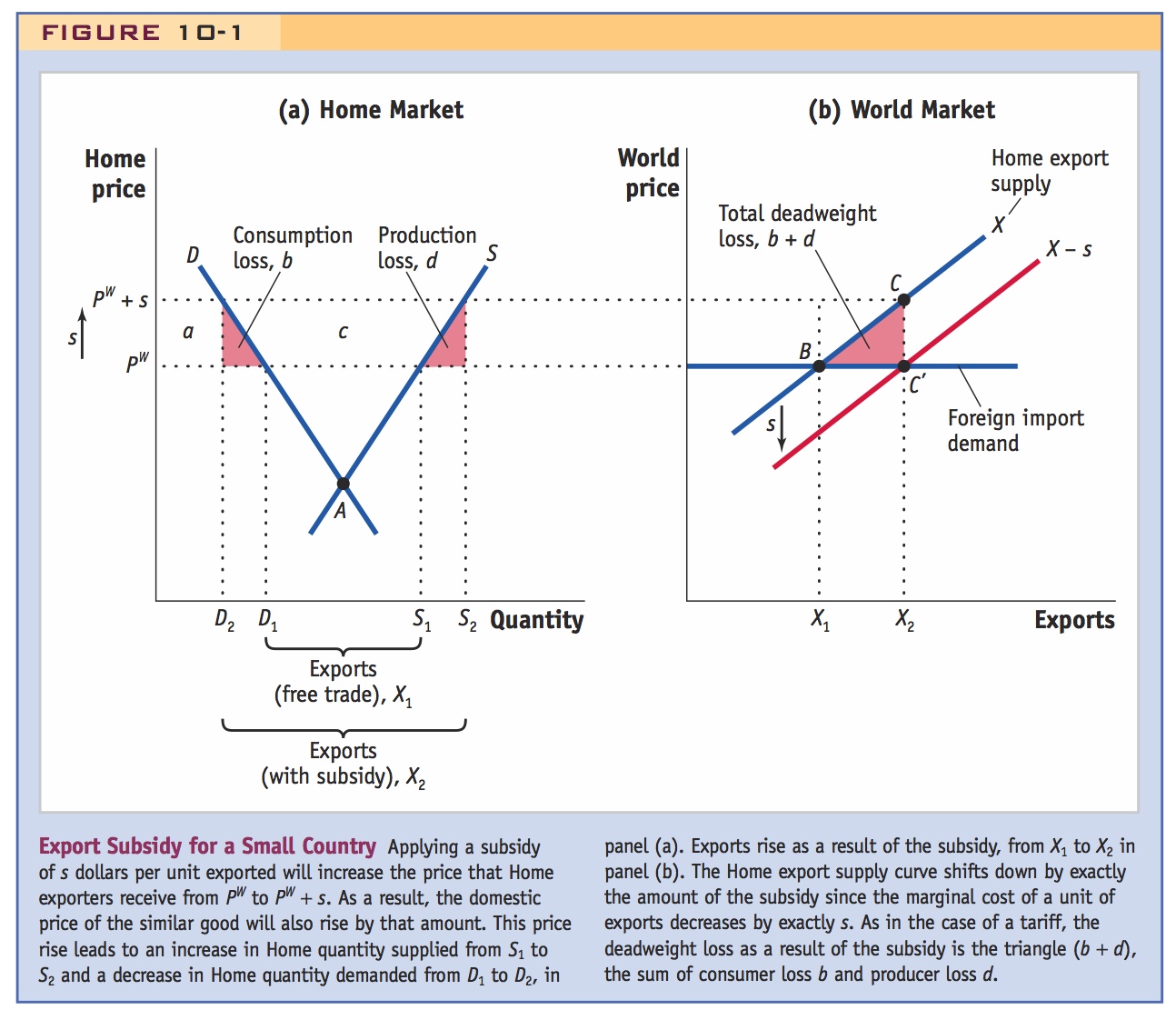

Consider a small country exporting sugar. The Home no-trade equilibrium is at point A in Figure 10-1. With free trade, Home faces the world price of sugar PW. In panel (a) of Figure 10-1, the quantity supplied in Home at that price is S1 and the quantity demanded is D1 tons of sugar. Because quantity demanded is less than quantity supplied, the Home country exports X1 = S1 − D1 tons under free trade. That quantity of exports is shown as point B in panel (b) corresponding to the free-trade price of PW. By determining the level of exports at other prices, we can trace out the Home export supply curve X.

Impact of an Export Subsidy

Highlight the similarities of this analysis to that on tariffs.

Now suppose that because the government wishes to boost the exports of the domestic sugar producers, each ton of sugar exported receives a subsidy of s dollars from the government. Panel (a) of Figure 10-1 traces the effect of this subsidy on the domestic economy. With an export subsidy of s dollars per ton, exporters will receive PW + s for each ton exported rather than the lower free-trade price PW. Because they are allowed to export any amount they want at the subsidized price, the Home firms will not accept a price less than PW + s for their domestic sales: if the domestic price was less than PW + s, the firms would just export all their sugar at the higher price. Thus, the domestic price for sugar must rise to PW + s so that it equals the export price received by Home firms.

333

Note that export subsidies are often combined with import tariffs.

Notice that with the domestic sugar price rising to PW + s, Home consumers could in principle import sugar at the price of PW rather than buy it from local firms. To prevent imports from coming into the country, we assume that the Home government has imposed an import tariff equal to (or higher than) the amount of the export subsidy. This is a realistic assumption. Many subsidized agricultural products that are exported are also protected by an import tariff to prevent consumers from buying at lower world prices. We see that the combined effect of the export subsidy and import tariff is to raise the price paid by Home consumers and received by Home firms.

With the price rising to PW + s, the quantity supplied in Home increases to S2, while the quantity demanded falls to D2 in panel (a). Therefore, Home exports increase to X2 = S2 − D2. The change in the quantity of exports can be thought of in two ways as reflected by points C and C′ in panel (b). On one hand, if we were to measure the Home price PW on the vertical axis, point C is on the original Home export supply curve X: that is, the rise in Home price has resulted in a movement along Home’s initial supply curve from point B to C since the quantity of exports has increased with the Home price.

On the other hand, with the vertical axis of panel (b) measuring the world price and given our small-country assumption that the world price is fixed at PW, the increase in exports from X1 to X2 because of the subsidy can be interpreted as a shift of the domestic export supply curve to X − s, which includes point C′. Recall from Chapter 8 that the export supply curve shifts by precisely the amount of the tariff. Here, because the export subsidy is like a negative tariff, the Home export supply curve shifts down by exactly the amount s. In other words, the subsidy allows firms to sell their goods to the world market at a price exactly s dollars lower at any point on the export supply curve; thus, the export supply curve shifts down. According to our small-country assumption, Home is a price taker in the world market and thus always sells abroad at the world price PW; the only difference is that with the subsidy, Home exports higher quantities.

Summary From the domestic perspective, the export subsidy increases both the price and quantity of exports, a movement along the domestic export supply curve. From the world perspective, the export subsidy results in an increase in export supply and, given an unchanged world price (because of the small-country assumption), the export supply curve shifts down by the amount of the subsidy s. As was the case with a tariff, the subsidy has driven a wedge between what domestic exporters receive (PW + s at point C) and what importers abroad pay (PW at point C′).

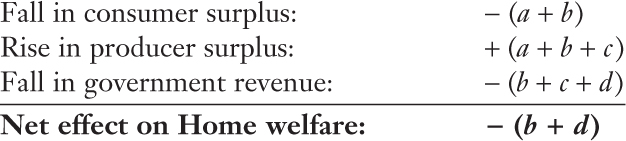

Impact of the Subsidy on Home Welfare Our next step is to determine the impact of the subsidy on the welfare of the exporting country. The rise in Home price lowers consumer surplus by the amount (a + b) in panel (a). That is the area between the two prices (PW and PW + s) and underneath the demand curve D. On the other hand, the price increase raises producer surplus by the amount (a + b + c), the area between the two prices (PW and PW + s), and above the supply curve S. Finally, we need to determine the effect on government revenue. The export subsidy costs the government s per unit exported, or s · X2 in total. That revenue cost is shown by the area (b + c + d).

334

Adding up the impact on consumers, producers, and government revenue, the overall impact of the export subsidy is

The triangle (b + d) in panel (b) is the net loss or deadweight loss due to the subsidy in a small country. The result that an export subsidy leads to a deadweight loss for the exporter is similar to the result that a tariff leads to a deadweight loss for an importing country. As with a tariff, the areas b and d can be given precise interpretations. The triangle d equals the increase in marginal costs for the extra units produced because of the subsidy and can be interpreted as the production loss or the efficiency loss for the economy. The area of the triangle b can be interpreted as the drop in consumer surplus for those individuals no longer consuming the units between D1 and D2, which we call the consumption loss for the economy. The combination of the production and consumption losses is the deadweight loss for the exporting country.