6 Export Quotas

This example will get their attention, but so will China in the ensuing application.

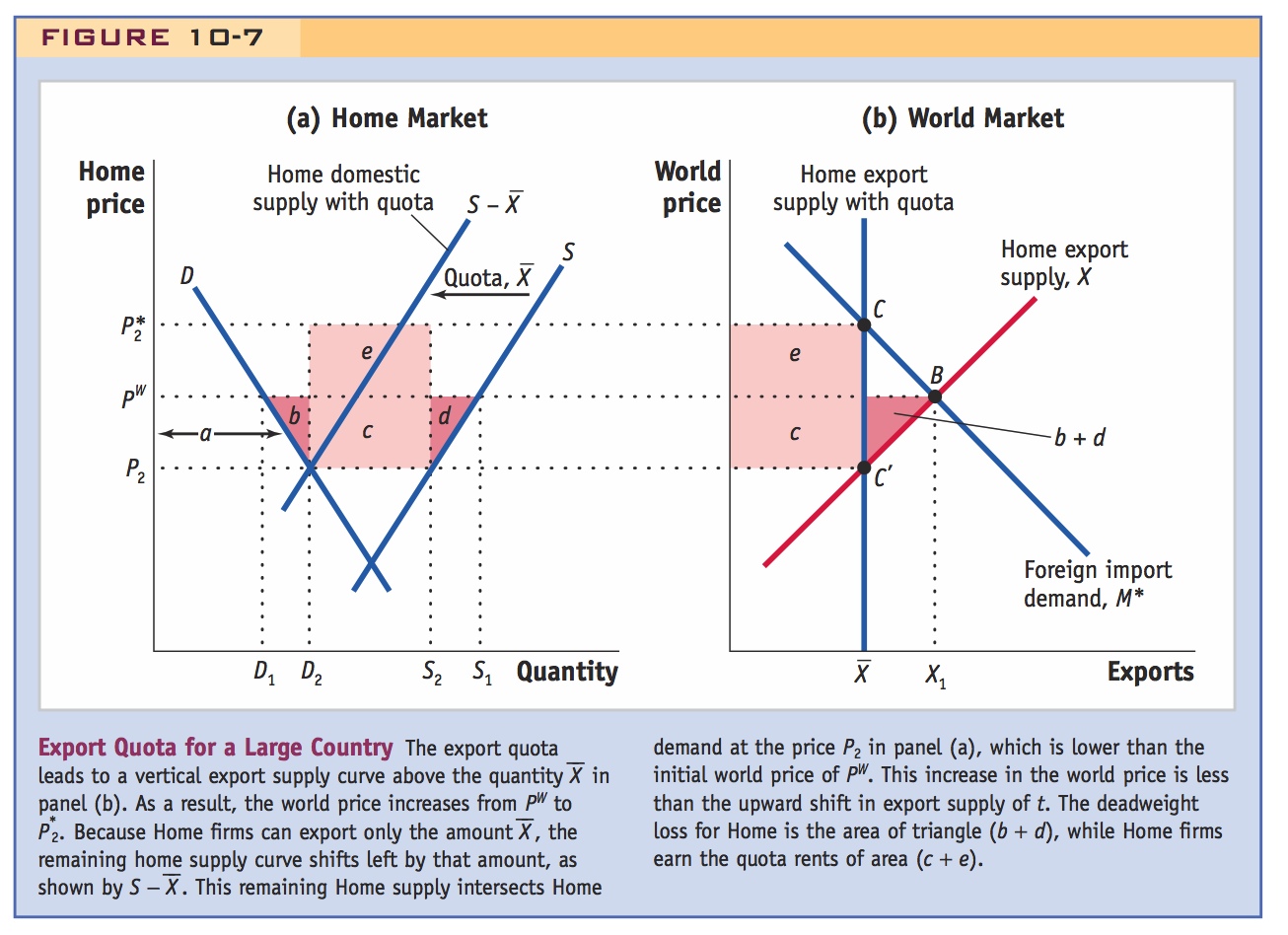

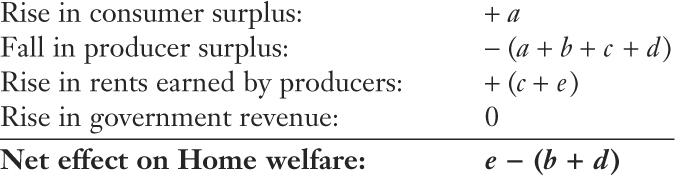

Export quotas limit the amount firms can export. OPEC is a famous example.The quota increases the amount sold domestically, lowering the Home price. However, Home export supply becomes perfectly inelastic at the quota so that, for a large country, the world price increases (the TOT improves).

Welfare effects: Home consumer surplus increases because price is lower and quantity higher. Producer surplus is more complicated. Given a lower Home price and a restricted quantity, producer surplus would fall. However, firms also earn quota rents equal to the difference between world and domestic prices multiplied by the amount of the quota. The deadweight loss is the same as for an export tariff, except that the government gets no revenue; instead domestic firms earn quota rents.

The finding that a large country can gain from an export tariff gives a government an added reason to use this policy, in addition to earning the tariff revenue. There is one other export policy that also benefits the large country applying it: an export quota, which is a limit on the amount that firms are allowed to export. The most well-known system of export quotas in the world today is the system used by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which includes six countries in the Middle East, four in Africa, and two in South America. OPEC sets limits on the amount of oil that can be exported by each country, and by limiting oil exports in this way, it keeps world petroleum prices high. Those high prices benefit not only OPEC’s member countries, but also other oil-exporting countries that do not belong to OPEC. (At the same time, the high prices clearly harm oil-importing countries). The oil companies themselves benefit from the export quotas because they earn the higher prices. Thus, the export quota is different from an export tariff (which is, in effect, a tax on firms that lowers their producer surplus).

348

We can use Figure 10-7 to illustrate the effect of an export quota. This figure is similar to Figure 10-6 because it deals with a large exporting country. Initially under free trade, the world trade price occurs at the intersection of Home export supply X and Foreign import demand M*, at point B in panel (b) with exports of X1. Now suppose that the Home country imposes a quota that limits its exports to the quantity  < X1. We can think of the export supply curve as a vertical line at the amount

< X1. We can think of the export supply curve as a vertical line at the amount  . A vertical line at

. A vertical line at  would intersect Foreign import demand at the point C, leading to a higher world price of

would intersect Foreign import demand at the point C, leading to a higher world price of  > PW.

> PW.

That higher world price is earned by the Home producers. But because they export less ( rather than the free trade amount X1), they sell more locally. Local sales can be found by subtracting exports of

rather than the free trade amount X1), they sell more locally. Local sales can be found by subtracting exports of  from the Home supply curve in panel (a), shifting the remaining Home supply left to the curve labeled S −

from the Home supply curve in panel (a), shifting the remaining Home supply left to the curve labeled S −  . The intersection of this remaining Home supply with Home demand occurs at the price P2 in panel (a), which is lower than the initial world price of PW. As we found for the export tariff in Figure 10-6, the fall in the Home price leads to an increase in Home demand from D1 to D2. That quantity is the amount that Home firms supply to the local market. The total amount supplied by Home firms is D2 +

. The intersection of this remaining Home supply with Home demand occurs at the price P2 in panel (a), which is lower than the initial world price of PW. As we found for the export tariff in Figure 10-6, the fall in the Home price leads to an increase in Home demand from D1 to D2. That quantity is the amount that Home firms supply to the local market. The total amount supplied by Home firms is D2 +  = S2, which has fallen in relation to the free-trade supply of S1. So we see that a side-effect of the export quota is to limit the total sales of Home firms.

= S2, which has fallen in relation to the free-trade supply of S1. So we see that a side-effect of the export quota is to limit the total sales of Home firms.

349

Let’s compare the welfare effects of the export quota with those of the export tariff. Home consumers gain the same amount of consumer surplus a due to lower domestic prices. The change in producer surplus is more complicated. If producers earned the lower price of P2 on all their quantity sold, as they do with the export tariff, then they would lose (a + b + c + d) in producer surplus. But under the export quota they also earn rents of (c + e) on their export sales, which offsets the loss in producer surplus. These rents equal the difference between the Home and world prices,  − P2, times the amount exported

− P2, times the amount exported  . A portion of these rents—the area e—is the rise in the world price times the amount exported, or the terms-of-trade gain for the exporter; the remaining amount of rents—the area c—offsets some of the loss in producer surplus. The government does not collect any revenue under the export quota, because the firms themselves earn rents from the higher export prices.

. A portion of these rents—the area e—is the rise in the world price times the amount exported, or the terms-of-trade gain for the exporter; the remaining amount of rents—the area c—offsets some of the loss in producer surplus. The government does not collect any revenue under the export quota, because the firms themselves earn rents from the higher export prices.

Identical to the export tariff, except that forms get the quota rent rather than the government getting it as tariff revenue.

The overall impact of the export quota is:

Most likely to be positive if there is a large TOT gain. Ask the students if they think this might apply to OPEC, and if so when and why.

To summarize, the overall effect of the export quota on the Home country welfare is the same as the export tariff, with a net effect on welfare of e − (b + d). If this amount is positive, then Home gains from the export quota. The effects of the quota on Home firms and the government differ from those of the tariff. Under the export tariff the Home government earns revenue of (c + e), while under the export quota that amount is earned instead as quota rents by Home firms.

This conclusion is the same as the one we reached in Chapter 8, when we examined the ways that import quotas can be allocated. One of those ways was by using a “voluntary” export restraint (VER), which is put in place by the exporting country rather than the importing country. The VER and the export quota are the same idea with different names. In both cases, the restriction on exports raises the world price. Firms in the exporting country can sell at that higher world price, so they earn the quota rents, with no effect on government revenue. In the following application, we look at how China used export quotas to limit its export of some mineral products.

China uses export quotas in steel and in mineral products. Imported countries complained because this raised prices of several mineral products. They complained to the WTO. The WTO restricts export quotas, but allows an exception for “export prohibitions or restrictions temporarily applied to prevent critical shortages of foodstuffs or other products essential” to the country. China invoked this exception, but the WTO rejected it. China is appealing. China also began to employ export quotas for rare earth minerals. Other countries filed a complaint with the WTO, which ruled against China again. However, China has now curtailed its export quotas and is using production subsidies for rare earth minerals.

Chinese Export Policies in Mineral Products

Like many developing countries, China uses a wide variety of export policies. Export tariffs ranging from 10% to 40% are applied to steel products, for example, which create a source of revenue for the government. In addition, China has applied both tariffs and quotas to its exports of mineral products. The policies that China has applied to mineral exports have attracted international attention recently, since some of these minerals are essential to the production of goods in other countries. As we saw in Figures 10-6 and 10-7, export tariffs and export quotas both increase the world price, making it more expensive for other countries to obtain a product and at the same time benefiting the exporting country with a terms-of-trade gain.

350

In 2009, the United States, the European Union, and Mexico filed a case against China at the World Trade Organization (WTO), charging that the export tariffs and export quotas that China applied on bauxite, zinc, yellow phosphorus, and six other industrial minerals, distorted the pattern of international trade.5 Export restrictions of this type are banned under Article XI of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (see Side Bar: Key Provisions of the GATT, Chapter 8). When China joined the WTO in 2001, it was required to eliminate its export restrictions, including those on minerals. But an exception to Article XI states that this rule does not apply to “export prohibitions or restrictions temporarily applied to prevent or relieve critical shortages of foodstuffs or other products essential to the exporting contracting party.” For example, a country facing a food shortage can restrict its food exports to keep the food at home. In its response to this 2009 case, China claimed that this exception applied to its exports of industrial minerals; China claimed that it was restricting its exports of the minerals because they were needed by Chinese industries using these products (such as the solar panel industry), and also because the export quota would limit the total amount sold of these precious resources and leave more in the ground for future use. But in July 2011, the WTO ruled that this exception did not apply to China’s exports of these products, and that it must remove its export restrictions on industrial minerals. China filed an appeal, but the WTO reaffirmed the ruling again in January 2012.

This legal battle at the WTO was closely watched around the world, because shortly after the case was filed in 2009, China also started applying export quotas to other mineral products: “rare earth” minerals, such as lanthanum (used in batteries and lighting) and neodymium (used in making permanent magnets, which are found in high-tech products ranging from smartphones to hybrid cars to wind turbines).6 At that time, China controlled more than 95% of the world production and exports of these minerals. The export quotas applied by China contributed to a rise in the world prices of these products. For example, the price of lanthanum went from $6 per kilogram in 2009 to $60 in 2010 to $151 in 2011, and then back down to $36 in 2012. The high world prices made it profitable for other nations to supply the minerals: Australia opened a mine and the United States reopened a mine in the Mojave Desert that had closed a decade earlier for environmental reasons. The U.S. mine includes deposits of light rare earth elements, such as neodymium, as well as the heavy rare elements terbium, yttrium, and dysprosium (which are needed to manufacture wind turbines and solar cells).7 These new sources of supply led to the price drop in 2012.

351

In March 2012, the United States, the European Union, and Japan filed another WTO case against China charging that it applied unfair export restrictions on its rare earth minerals, as well as tungsten and molybdenum. The first step in such a case is for the parties involved (the United States, Europe, and Japan on one side; China on the other) to see whether the charges can be resolved through consultations at the WTO. Those consultations failed to satisfy either side, and in September 2012, the case went to a dispute settlement panel at the WTO. The Chinese government appealed to Article XX of the GATT, which allows for an exception to GATT rules in cases “relating to the conservation of exhaustible natural resources.” But the WTO ruled against China, who is expected to appeal.

Regardless of the ultimate outcome of that case, it appears that China has already changed its policies on rare earth minerals. By the end of 2012, China realized that its policy of export quotas for rare earth minerals was not having the desired effect of maintaining high world prices. It therefore shifted away from a strict reliance on export quotas, and introduced subsidies to help producers who were losing money. These new policies are described in Headlines: China Signals Support for Rare Earths. The new subsidy policy might also lead to objections from the United States, the European Union, and Japan. But as we have seen earlier in this chapter, it is more difficult for the WTO to control subsidies (which are commonly used in agriculture) than to control export quotas.

A final feature of international trade in rare earth minerals is important to recognize: the mining and processing of these minerals poses an environmental risk, because rare earth minerals are frequently found with radioactive ores like thorium or uranium. Processing these minerals therefore leads to low-grade radioactive waste as a by-product. That aspect of rare earth minerals leads to protests against the establishment of new mines. The Lynas Corporation mine in Australia, mentioned in the Headlines article, processes the minerals obtained there in Malaysia. That processing facility was targeted by protesters in Malaysia, led by a retired math teacher named Tan Bun Teet. Although Mr. Tan and the other protestors did not succeed in preventing the processing facility from being opened, they did delay it and also put pressure on the company to ensure that the radioactive waste would be exported from Malaysia, in accordance with that country’s laws. But where will this waste go? This environmental dilemma arises because of the exploding worldwide demand for high-tech products (including your own cell phone), whose manufacturing involves environmental risks. This case illustrates the potential interaction between international trade and the environment, a topic we examine in more detail in the next chapter.

A discussion of changes in China’s rare earths policies