2 Migration and Foreign Direct Investment

1. Objectives: Discuss flows of labor and capital across borders

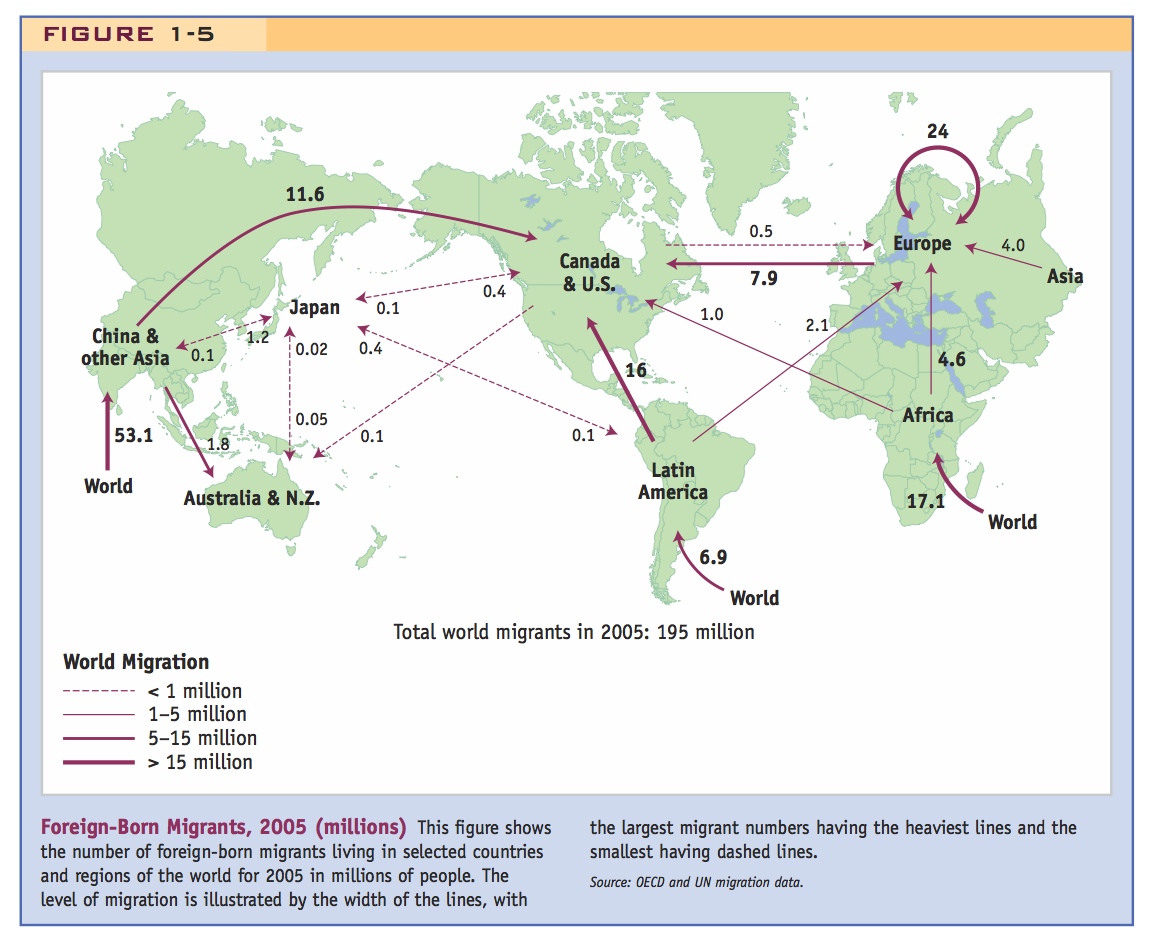

2. Map of Migration

a. Most immigration occurs between developing countries, e.g., in Africa and Asia

b. Migrants would probably prefer to go to high-wage industrial countries; however, they are prevented from doing so by restrictions on immigration.

c. Trade in goods (and services) can substitute for migration by raising wages in the export sectors of poorer countries.

d. European and U.S. Immigration

Europe: Entry of Central European countries into the EU created strong incentives for immigration from the low-wage east to the high-wage west. Germany and Austria wanted a 7-year moratorium from these countries; Britain agreed to accept immigrants, but at the cost of creating political tensions.

United States: 13 million Mexicans in the U.S. in 2005, half of which were there illegally.

Immigration policy is hotly debated.

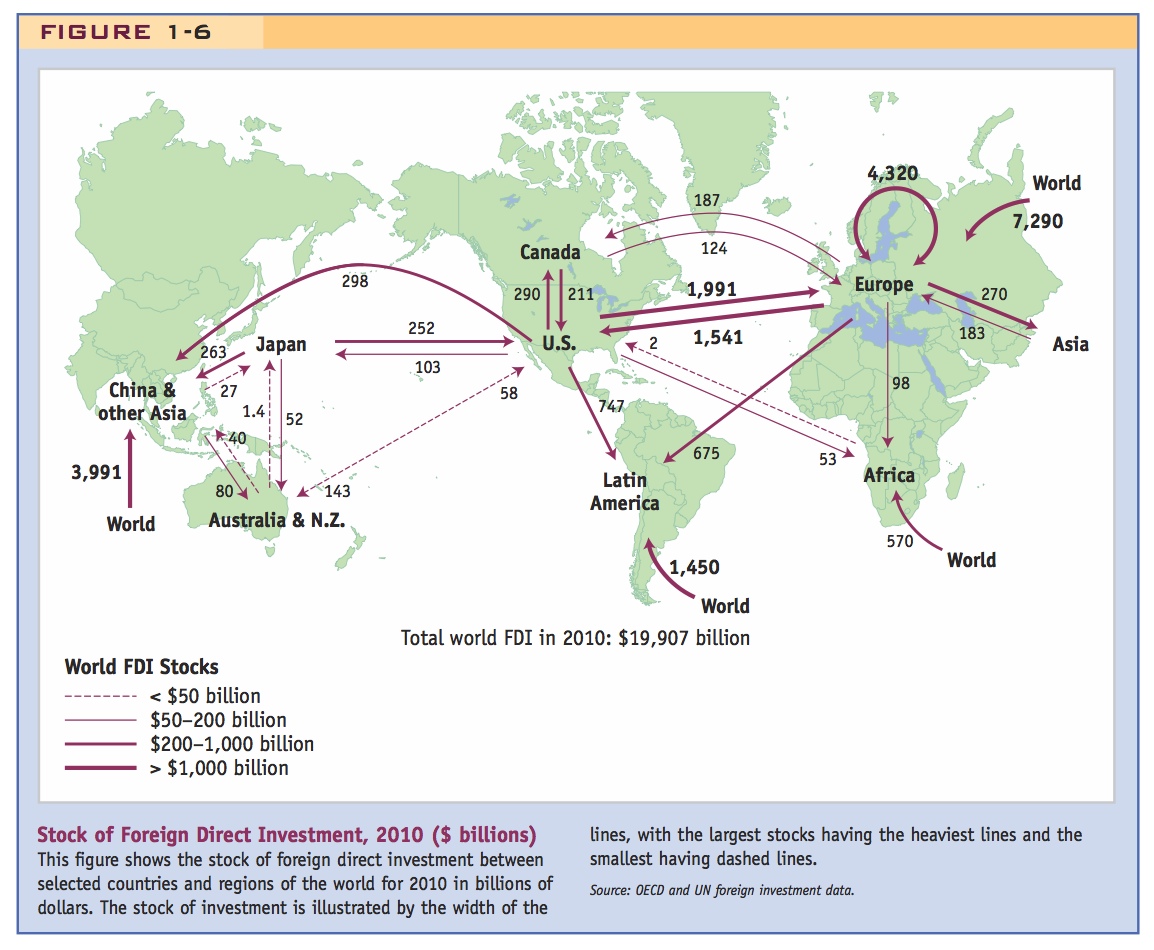

3. Map of Foreign Direct Investment

a. Most FDI occurs in, or is owned by firms in, OECD countries, although China is beginning to make FDIs in Asia and Latin America.

b. Types of FDIs:

i. Horizontal (FDI between industrial countries): Advantages include avoiding tariffs, improved access to local markets, sharing technical expertise, and avoiding duplication of products

ii. Vertical (FDI from industrial to developing countries): Main advantage is cheap labor, although firms also make FDIs in China to avoid tariffs and find local partners

c. European and U.S. FDIs: Most FDI is horizontal FDI between industrialized countries, particularly the U.S. and Europe

d. FDI in the Americas: Much horizontal FDI between U.S. and Canada, also large vertical FDIs from U.S., particularly with Mexico and Brazil

e. FDI with Asia: Horizontal FDIs between U.S. and Japan and between Europe and Japan; also vertical FDIs elsewhere in Asia, particularly China. However, Chinese firms also engage in reverse-vertical FDI, in order to acquire technological knowledge from developed economies, and to acquire companies that produce goods needed by the growing Chinese economy

In addition to examining the reasons for and effects of international trade (the flow of goods and services between countries), we will also analyze migration, the movement of people across borders, and foreign direct investment, the movement of capital across borders. All three of these flows affect the economy of a nation that opens its borders to interact with other nations.

Map of Migration

Figure 1-5 is another neat picture. Here too let the students infer its messages.

In Figure 1-5, we show a map of the number of migrants around the world. The values shown are the number of people in 2005 (this is the most recent year for which these data are available) who were living (legally or illegally) in a country other than the one in which they were born. For this map, we combine two different sources of data: (1) the movement of people from one country to another, reported for just the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries and shown by arrows from one country to another7, and (2) the number of foreign-born located in each region (but without data on their country of origin), shown by the bold arrows from World into Asia, Africa, and Latin America.8

In 2005 there were 62 million foreign-born people living in the OECD countries. But that was less than one-third of the total number of foreign-born people worldwide, which was 195 million. These figures show that unlike trade (much of which occurs between the OECD countries), the majority of immigration occurs outside the OECD between countries that are less wealthy. Asia, for example, was home to 53.1 million migrants in 2005, and Africa was home to 17.1 million migrants. Latin America has 6.9 million foreign-born people living there. We expect that many of these immigrants come from the same continent where they are now living but have had to move from one country to another for employment or other reasons such as famine and war.9

17

Given the choice, these migrants would probably rather move to a high-wage, industrial country. But people cannot just move to another country as can the goods and services that move in international trade. All countries have restrictions on who can enter and work there. In many OECD countries, these restrictions are in place because policy makers fear that immigrants from low-wage countries will drive down the wages for a country’s own less skilled workers. Whether or not that fear is justified, immigration is a hotly debated political issue in many countries, including Europe and the United States. As a result, the flow of people between countries is much less free than the flow of goods.

18

The limitation on migration out of the low-wage countries is offset partially by the ability of these countries to export products instead. International trade can act as a substitute for movements of labor or capital across borders, in the sense that trade can raise the living standard of workers in the same way that moving to a higher-wage country can. The increased openness to trade in the world economy since World War II has provided opportunities for workers to benefit through trade by working in export industries, even when restrictions on migration prevent them from directly earning higher incomes abroad.

European and U.S. Immigration We have just learned that restrictions on migration, especially into the wealthier countries, limit the movement of people between countries. Let us see how such restrictions are reflected in recent policy actions in two regions: the European Union and the United States.

Prior to 2004 the European Union (EU) consisted of 15 countries in western Europe, and labor mobility was very open between them.10 On May 1, 2004, 10 more countries of central Europe were added: Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia. These countries had per capita incomes that were only about one-quarter of the average per capita incomes in those western European countries that were already EU members. This large difference in wages created a strong incentive for labor migration. In principle, citizens from these newly added countries were permitted to work anywhere in the EU. As shown in Figure 1-5, in 2005 there were 24 million people from Europe living in an EU country in which they were not born. In practice, however, fears of this impending inflow of labor led to policy disagreements among the countries involved.

At this point, allow some freewheeling class discussion on these issues. Then promise theory and data that will lend more structure to the debate.

Germany and Austria, which border some of the new member countries, argued for a 7-year moratorium on allowing labor mobility from new members, if desired by the host countries. Britain and Ireland, on the other hand, promised to open up their countries to workers from the new EU members. In January 2007 two more countries joined the EU: Romania and Bulgaria. Legal immigration from these countries in the expanded EU, together with legal and illegal immigration from other countries, has put strains on the political system in Britain. All major political parties spoke in favor of limiting immigration from outside the EU, and this issue may have contributed to the ousting of the Labour Party in Britain in the election of May 2010.

A second example of recent migration policy is from the United States. As shown in Figure 1-5, there were 16 million people from Latin America living in the United States and Canada in 2005, and the largest group of these migrants is Mexicans living in the United States. It is estimated that today close to 13 million Mexicans are living in the United States, about half legally and half illegally. This number is more than 10% of Mexico’s population of 115 million. The concern that immigration will drive down wages applies to Mexican migration to the United States and is amplified by the exceptionally high number of illegal immigrants. It is no surprise, then, that immigration policy is a frequent topic of debate in the United States.

There is a widespread perception among policy makers in the United States that the current immigration system is not working and needs to be fixed. In 2007 President George W. Bush attempted an immigration reform, but it was not supported by the Congress. During his first term as president, Barack Obama also promised to pursue immigration reform. But that promise had to wait for other policy actions, most notably the health-care reform bill and the reform of the financial system following the 2008–2009 crisis, both of which delayed the discussion of immigration. As President Obama began his second term in 2013, he again promised action on immigration reform, and that idea is supported by members of both parties in the United States. As of the time of writing, it remains to be seen what type of immigration bill will be enacted during President Obama’s administration.

19

Map of Foreign Direct Investment

For Figure 1-6 also, let students play with it and think on their own.

As mentioned earlier in the chapter, foreign direct investment (FDI) occurs when a firm in one country owns (in part or in whole) a company or property in another country. Figure 1-6 shows the principal stocks of FDI in 2010, with the magnitude of the stocks illustrated by the width of the lines. As we did for migration, we again combine two sources of information: (1) stocks of FDI found in the OECD countries that are owned by another country, shown by arrows from the country of ownership to the country of location, and (2) FDI stocks from anywhere in the world found in Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America.

20

In 2010 the total value of FDI stocks located in the OECD countries or owned by those countries was $17 trillion. That value is 85% of the total world stock of FDI, which was $19.9 trillion in 2010. So unlike our findings for immigration, the vast majority of FDI is located in or owned by firms in the OECD countries. The concentration of FDI among wealthy countries is even more pronounced than the concentration of international trade flows. The FDI stock in Africa ($570 billion) is just over one-third of the stock in Latin America ($1,450 billion), which in turn is less than one-half of the FDI into China and other Asian countries ($3,991 billion). Most of this FDI is from industrial countries, but Chinese firms have begun to acquire land in Africa and Latin America for agriculture and resource extraction, as well as purchase companies in the industrial countries, as we discuss below.

FDI can be described in one of two ways: horizontal FDI or vertical FDI.

Horizontal FDI The majority of FDI occurs between industrial countries, when a firm from one industrial country owns a company in another industrial country. We refer to these flows between industrial countries as horizontal FDI. Recent examples have occurred in the automobile industry, such as the 2009 purchase of Chrysler by Fiat, an Italian firm.

There are many reasons why companies want to acquire firms in another industrial country. First, having a plant abroad allows the parent firm to avoid any tariffs from exporting to a foreign market because it can instead produce and sell locally in that market. For example, as early as the 1950s and 1960s, American auto manufacturers produced and sold cars in Europe to avoid having to pay any tariffs. In the 1980s and 1990s many Japanese auto firms opened plants in the United States to avoid U.S. import quotas (restrictions on the amount imported). Today, more Japanese cars are built in the United States than are imported from Japan.

Second, having a foreign subsidiary abroad also provides improved access to that economy because the local firms will have better facilities and information for marketing products. For example, Toyota Motor Sales U.S.A. is a wholly owned subsidiary of Toyota Motor Corporation in Japan and markets Toyota cars and trucks in the United States. Many other foreign firms selling in the United States have similar local retail firms. Third, an alliance between the production divisions of firms allows technical expertise to be shared and avoids possible duplication of products. Examples are the American and Canadian divisions of General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler, which have operated plants specializing in different vehicles on both sides of the border (in Detroit, Michigan, and Windsor, Ontario) for decades. There are many reasons for horizontal FDI, which is really just a way for a firm to expand its business across international borders.

Vertical FDI The other form of FDI occurs when a firm from an industrial country owns a plant in a developing country, which we call vertical FDI. Low wages are the principal reasons that firms shift production abroad to developing countries. In the traditional view of FDI, firms from industrial economies use their technological expertise and combine this with inexpensive labor in developing countries to produce goods for the world market. This is a reasonable view of FDI in China, although as we have already seen, much of worldwide FDI does not fit this traditional view because it is between industrial countries.

21

In addition to taking advantage of low wages, firms have entered the Chinese market to avoid tariffs and acquire local partners to sell there. For example, China formerly had high tariffs on automobile imports, so many auto producers from the United States, Germany, and Japan established plants there, always with a Chinese partner, enabling them to sell more easily in that market. China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, which means that it has reduced its tariffs on nearly all imports, including automobiles. Nevertheless, the foreign automobile firms are planning to remain and are now beginning to export cars from China.

European and U.S. FDI Turning back now to Figure 1-6, the largest stocks of FDI are within Europe; these stocks amounted to $11.6 trillion in 2010, or more than one-half of the world total, with $4.3 trillion coming from other European countries. In addition, the horizontal FDI from Europe to the United States ($1.5 trillion) and that from the United States to Europe ($2.0 trillion) are very substantial. An example of a European direct investment in the United States was the merger of the German company Daimler-Benz (which produces the Mercedes-Benz car) and Chrysler Corporation in 1998, resulting in the firm DaimlerChrysler. That deal lasted for fewer than 10 years, however, and in May 2007 DaimlerChrysler sold the Chrysler firm back to an American financial company, Cerberus Capital Management, so Chrysler returned to American ownership. Then, in 2009, Chrysler was again sold to a European automobile firm, Fiat. An example of American direct investment in Europe was Ford Motor Company’s acquisition of the British firm Jaguar (in 1989) and the Swedish firm Volvo (in 1999). The United States consistently ranks as the top country for both inbound and outbound FDI stocks ($2.5 trillion and $4.3 trillion in 2010, respectively), followed by the United Kingdom and then France.

Adding up the stocks within Europe and between Europe and the United States, we find that they total $7.9 trillion, or more than one-third (39%) of the world total. That share is even larger than the roughly one-quarter (27%) of worldwide trade that occurs within Europe and between Europe and the United States (see Table 1-1). This finding illustrates that the greatest amount of FDI is horizontal FDI between the industrial countries.

FDI in the Americas There are also substantial amounts of FDI shown in Figure 1-6 among the United States, Canada, and Latin America. The United States had a stock of direct investments of $290 billion in Canada in 2010, and Canada invested $211 billion in the United States. The United States had a stock of direct investments of $747 billion in Latin America, principally in Mexico. Brazil and Mexico are two of the largest recipients of FDI among developing countries, after China. In 2010 Mexico had a FDI stock of $265 billion, and Brazil had a stock of $514 billion, accounting for about one-half of the total $1,450 billion in FDI to Latin America. These are examples of vertical FDI, prompted by the opportunity to produce goods at lower wages than in the industrial countries.

FDI with Asia The direct investments between the United States and Japan and between Europe and Japan are horizontal FDI. In addition to Japan, the rest of Asia shows a large amount of FDI in Figure 1-6. The United States had direct investments of $298 billion in the rest of Asia, especially China, while Europe had a direct investment of $270 billion in Asia. These stocks are also examples of vertical FDI, foreign direct investment from industrial to developing countries, to take advantage of low wages.

22

China has become the largest recipient country for FDI in Asia and the second largest recipient of FDI in the world (after the United States). The FDI stock in China and Hong Kong was $1,476 billion in 2010, which accounts for 37% of the total FDI into China and the rest of Asia ($4.0 trillion). There is some “double counting” in these numbers for China and Hong Kong because Hong Kong itself has direct investment in mainland China, which is funded in part by businesses on the mainland. This flow of funds from mainland China to Hong Kong and then back to China is called “round tripping,” and it is estimated that one-quarter to one-half of FDI flowing into China is funded that way.

Notice in Figure 1-6 that Asia has direct investment into the United States and Europe, or what we might call “reverse-vertical FDI.” Contrary to the traditional view of FDI, these are companies from developing countries buying firms in the industrial countries. Obviously, these companies are not going after low wages in the industrial countries; instead, they are acquiring the technological knowledge of those firms, which they can combine with low wages in their home countries. A widely publicized example was the purchase of IBM’s personal computer division by Lenovo, a Chinese firm. What expertise did Lenovo acquire from this purchase? According to media reports, Lenovo will acquire the management and international expertise of IBM and will even hire IBM executives to run the business. Instead of using FDI to acquire inexpensive labor, Lenovo has engaged in FDI to acquire expensive and highly skilled labor, which is what it needs to succeed in the computer industry.

Another example of reverse-vertical FDI from China is the 2009 purchase of Volvo (formerly a Swedish company) from Ford Motor Company, by the Chinese automaker Geely. In a later chapter, we will discuss how automobile companies from the United States, Europe, and Japan entered the automobile industry in China by buying partial ownership in Chinese firms, which allowed the Chinese firms to learn from their foreign partners. That process of learning the best technology continues in the case of Geely purchasing Volvo from Ford, but now it is the Chinese firm that is doing the buying rather than the American, European, or Japanese firms.

In addition to acquiring technical knowledge, Chinese firms have been actively investing in foreign companies whose products are needed to meet the growing demand of its 1.3 billion people. A recent example is the proposed purchase of the American firm Smithfield Foods, one of the largest producers of pork in the United States, by the Chinese firm Shuanghui International. Rising incomes have led to increased demand for pork in China, exceeding that country’s own ability to supply it. This example illustrates the more general trend of Chinese companies investing in natural resource and infrastructure projects around the world. As reported in The New York Times:11

[The proposed purchase of Smithfield] fulfills a major ambition of the Chinese government, to encourage companies to venture abroad by acquiring assets, resources and technical expertise. In North America, Africa and Australia, Chinese companies, flush with cash, are buying up land and resources to help a country that is plagued by water shortages and short of arable land, a situation exacerbated by a long running property and infrastructure boom.

23

As China continues to industrialize, which will raise the income of its consumers and the ability of its firms to invest overseas, we can expect that its firms and government will continue to look beyond its borders to provide for the needs of its population.