4 Policy Response to Dumping

1. Antidumping Duties

The WTO allows an importing country to impose a tariff when it can establish that another country is engaging in dumping. The amount of the duty is calculated as the difference between the exporter’s home price and the price in the importing country.

In the previous section, we learned that dumping is not unusual: a Foreign monopolist that discriminates between its local and export markets by charging different prices in each can end up charging a lower price in its export market. Furthermore, the price it charges in its export market might be less than its average cost of production and still be profitable. Our interest now is in understanding the policy response in the Home importing country.

299

Antidumping Duties

How to calculate the duty.

Under the rules of the WTO, an importing country is entitled to apply a tariff—called an antidumping duty—any time that a foreign firm is dumping its product. An imported product is being dumped if its price is below the price that the exporter charges in its own local market; if the exporter’s local price is not available, then dumping is determined by comparing the import price to (1) a price charged for the product in a third market or (2) the exporter’s average costs of production.10 If one of these criteria is satisfied, then the exporting firm is dumping and the importing country can respond with antidumping duty. The amount of the antidumping duty is calculated as the difference between the exporter’s local price and the “dumped” price in the importing country.

There are many examples of countries applying antidumping duties. In 2006 the European Union applied tariffs of 10% to 16.5% on shoes imported from China and 10% on shoes imported from Vietnam. These antidumping duties were justified because of the low prices at which the imported shoes are sold in Europe. These duties expired in 2011. A recent example of antidumping duties from the United States are those applied to the imports of solar panels from China, discussed next.

The United States has imposed antidumping duties on Chinese solar panels since 2012. It also imposes a countervailing duty to offset subsidies provided by the Chinese government. Export subsidies will be studied in Chapter 10.

a. Strategic Trade Policy?

Antidumping duties have two purposes: First, to raise domestic prices to protect domestic producers: As we saw in Section 2, imposing a tariff on a Foreign monopolist yields a TOT gain for the Home country. Can this make the Home economy better off? Probably not, as we will see below. Second, it may prevent predatory dumping when prices are set below MC in order to force domestic firms out of business. Predatory pricing is unlikely to happen, since the predator must believe that it can sustain its losses longer than its prey. To consider such a possibility requires a model that incorporates entry and exit decisions. We will develop such a model in Chapter 10.

b. Comparison with Safeguard Tariff

The tariff on trucks was a safeguard tariff, not an antidumping duty: Foreign firms perceive the tariff as fixed, but can alter the amount of the antidumping duty themselves by changing their prices in the importing country before the duty is imposed.

c. Calculation of Antidumping Duty

If the Foreign firm anticipates an antidumping duty it has an incentive to raise its price in Home in order to reduce the amount of the duty. This causes a TOT loss to home. It also creates the perverse incentive for Home firms to lobby for anti-dumping duties, even when dumping is not occurring.

United States Imports of Solar Panels from China

Since November 2012, the United States has applied antidumping duties on the imports of solar panels from China. In addition to the antidumping duties, another tariff—called a countervailing duty—has been applied against imports of solar panels from China. A countervailing duty is used when the Foreign government subsidizes its own exporting firms so that they can charge lower prices for their exports. We will examine export subsidies in the next chapter. For now, we’ll just indicate the amount of the subsidy provided by the Chinese government to their firms that export solar panels. Later in the chapter, we’ll discuss the type of subsidies the U.S. government provides to American producers of solar panels.

In October 2011, seven U.S. companies led by SolarWorld Industries America, based in Hillsboro, Oregon, filed a trade case against Chinese exporters of photovoltaic cells, or solar panels. These U.S. companies argued that the Chinese firms were dumping solar panels into the United States —that is, they were exporting them at less than the costs of production—and also that these firms were receiving substantial export subsidies from the Chinese government. These twin claims of dumping and of export subsidies triggered several investigations by the U.S. Department of Commerce and the International Trade Commission (ITC), to determine the U.S. response.

The ITC completed its first investigation in December 2011, and made a preliminary finding that the U.S. companies bringing the trade case had been harmed—or “materially injured”—by the U.S. imports of solar panels from China. From 2009 to 2011, imports of solar panels from China increased by four times, and their value grew from $640 million to more than $3 billion. During this period, several American solar panel producers went bankrupt, so it was not surprising that the ITC found material injury due to imports.

300

Following the ITC’s investigation, the U.S. Department of Commerce held two inquiries during 2012 to determine the extent of dumping and the extent of Chinese export subsidies. It is particularly difficult to determine the extent of dumping when the exporting firm is based in a nonmarket economy like China, because it is hard to determine the market-based costs of the firms. To address this difficulty, the Department of Commerce looked at the costs of production in another exporting country—Thailand—and used those costs to estimate what market-based costs in China would be.11 In a preliminary ruling in May 2012, and a later ruling in October 2012, the Department of Commerce found that a group of affiliated producers, all owned by Suntech Power Holdings, Co., Ltd., were selling in the United States at prices 32% below costs, and that a second group of producers were selling at 18% below costs. The 32% and 18% gaps include an export subsidy of about 11%. Because there was an additional export subsidy of 4% to 6% paid to the Chinese producers that was not reflected in the 32% and 18% gaps between costs and prices, tariffs of 36% were recommended for the first group of producers, and tariffs of 24% were recommended for the others.

In November 2012, the ITC made a final determination of material injury to the U.S. solar panel industry, and the tariffs went into effect. Not all American producers supported these tariffs, however, because they raised costs for firms such as SolarCity Corp., which finances and installs rooftop solar systems. These firms are the consumers of the imported solar panels and they face higher prices as a result of the tariffs. Despite the tariffs, the installation of solar panels is a thriving industry in the United States today, and the higher prices protect the remaining U.S. manufacturers of solar panels.

Strategic Trade Policy? The purpose of an antidumping duty is to raise the price of the dumped good in the importing Home country, thereby protecting the domestic producers of that good. There are two reasons for the Home government to use this policy. The first reason is that Foreign firms are acting like discriminating monopolists, as we discussed above. Then because we are dealing with dumping by a Foreign monopolist, we might expect that the antidumping duty, which is a tariff, will lead to a terms-of-trade gain for the Home country. That is, we might expect that the Foreign monopolist will absorb part of the tariff through lowering its own price, as was illustrated in Figure 9-7. It follows that the rise in the consumer price in the importing country is less than the full amount of the tariff, as was illustrated in the application dealing with Japanese compact trucks.

Does the application of antidumping duties lead to a terms-of-trade gain for the Home country, making this another example of strategic trade policy that can potentially benefit the Home country? In the upcoming analysis, we’ll find that the answer to this question is “no,” and that the antidumping provisions of U.S. trade law are overused and create a much greater cost for consumers and larger deadweight loss than does the less frequent application of tariffs under the safeguard provision, Article XIX of the GATT.12

301

A second reason for the Home government to use an antidumping duty is because of predatory dumping. Predatory dumping refers to a situation in which a Foreign firm sells at a price below its average costs with the intention of causing Home firms to suffer losses and, eventually, to leave the market because of bankruptcy. Predatory pricing behavior can occur within a country (between domestic firms), but when it occurs across borders between a Foreign and Home firm, it is called dumping. Economists generally believe that such predatory behavior is rare: the firm engaged in the predatory pricing behavior must believe that it can survive its own period of losses (due to low prices) for longer than the firm or firms it is trying to force out of the market. Furthermore, the other firms must have no other option except to exit the market even though the firm using the predatory pricing can survive. If we are truly dealing with a case of predatory dumping, then the discussion that follows (about the effect of an antidumping duty) does not really apply. Instead, we need to consider a more complicated model in which firms are deciding whether to enter and remain in the market. In the next chapter’s discussion of export subsidies, we analyze such a model. In this chapter, we focus on dumping by a discriminating Foreign monopoly and the effect of an antidumping duty in that case.

The important difference between a tariff per se and an antidumping duty.

Comparison with Safeguard Tariff It is important to recognize that the tariff on compact trucks, discussed in the earlier application, was not an antidumping duty. Rather, it was a safeguard tariff applied under Section 201 of the U.S. tariff code, or Article XIX of the GATT. Because the tariff on trucks was increased in the early 1980s and has not been changed since, it fits our assumption that Foreign firms treat the tariff as fixed. That assumption does not hold for antidumping duties, however, because Foreign exporting firms can influence the amount of an antidumping duty by their own choice of prices. In fact, the evidence shows that Foreign firms often change their prices and increase the price charged in the importing country even before an antidumping tariff is applied. To see why this occurs, let us review how the antidumping duty is calculated.

Calculation of Antidumping Duty The amount of an antidumping duty is calculated based on the Foreign firm’s local price. If its local price is $10 (after converting from Foreign’s currency to U.S. dollars), and its export price to the Home market is $6, then the antidumping tariff is calculated as the difference between these prices, $4 in our example. This method of calculating the tariff creates an incentive for the Foreign firm to raise its export price even before the tariff is applied so that the duty will be lower. If the Foreign firm charges an export price of $8 instead of $4 but maintains its local price of $10, then the antidumping tariff would be only $2. Alternatively, the Foreign firm could charge $10 in its export market (the same as its local price) and avoid the antidumping tariff altogether!

. . . and its consequences.

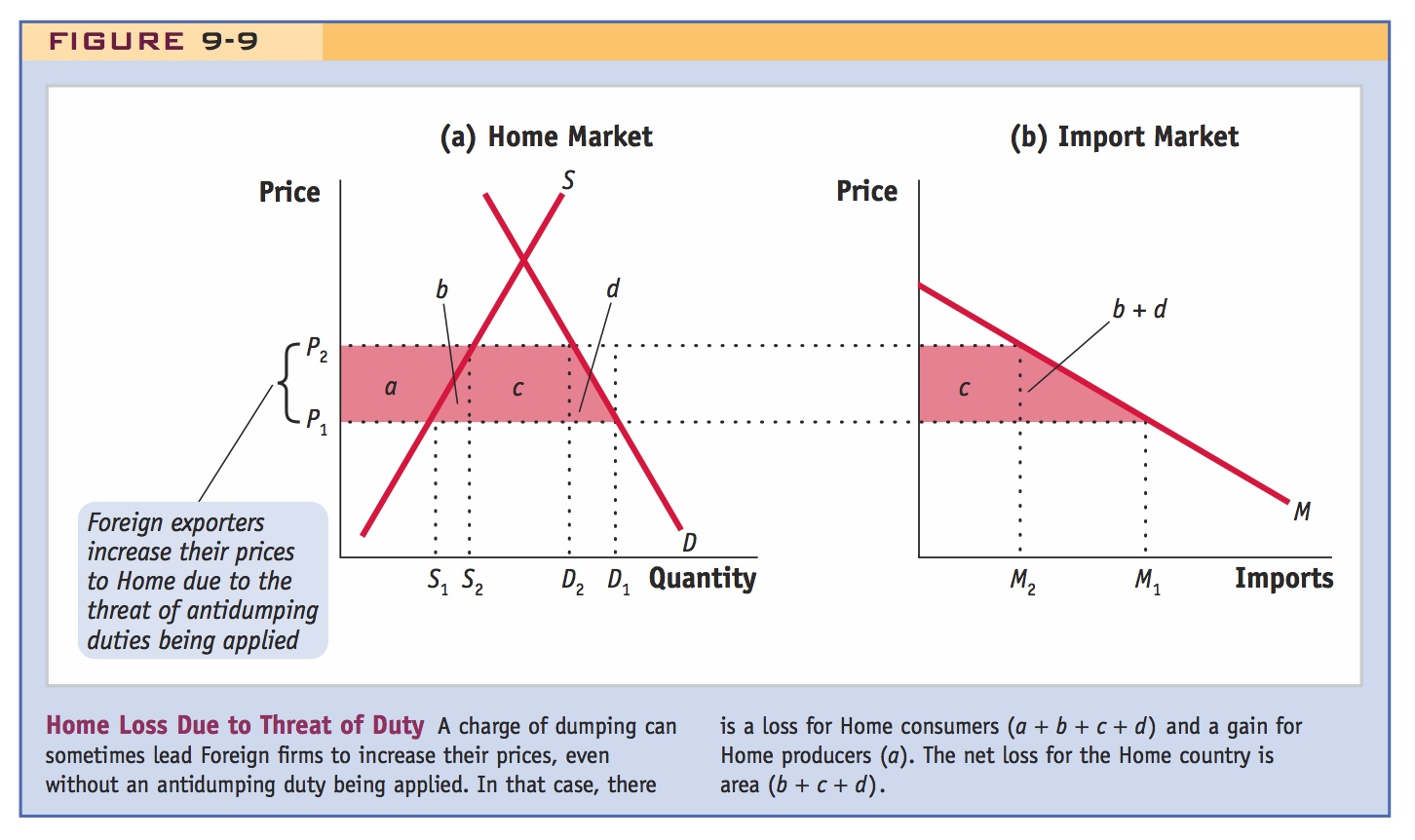

Thus, the calculation of an antidumping duty creates a strong incentive for Foreign firms to raise their export prices to reduce or avoid the duty. This increase in the import price results in a terms-of-trade loss for the Home country. Such an increase in the import price is illustrated in Figure 9-9 as the rise from price P1 to P2. This price increase leads to a gain for Home firms of area a, but a loss for Home consumers of area (a + b + c + d). There is no revenue collected when the duty is not imposed, so the net loss for the Home country is area (b + c + d). This loss is higher than the deadweight loss from a tariff (which is area b + d) and illustrates the extra costs associated with the threat of an antidumping duty.

302

Furthermore, the fact that Foreign firms will raise their prices to reduce the potential duty gives Home firms an incentive to charge Foreign firms with dumping, even if none is occurring: just the threat of an antidumping duty is enough to cause Foreign firms to raise their prices and reduce competition in the market for that good. As the following application shows, these incentives lead to excessive filings of antidumping cases.

Requests to the ITC for safeguard tariffs are relatively infrequent, while requests for antidumping duties are relatively frequent. Many of the antidumping cases are dropped prior to a ruling by the ITC, but still are settled at higher domestic prices. The annual cost of U.S. antidumping policies is equivalent to the deadweight loss of a uniform tariff of 6 percent across all imports.

Antidumping Duties Versus Safeguard Tariffs

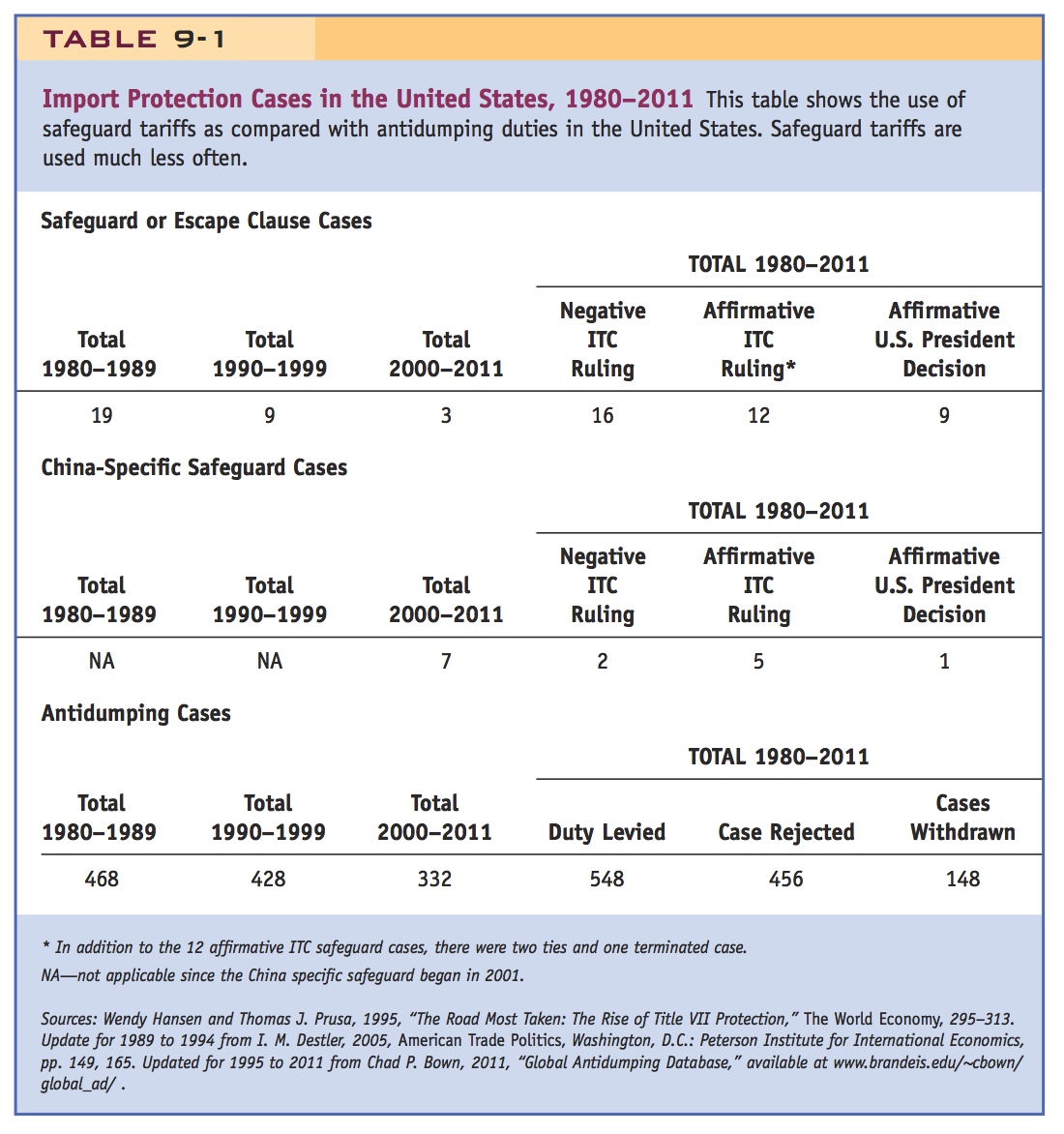

In the previous chapter, we discussed the “safeguard” provision in Article XIX of the GATT (Side Bar: Key Provisions of the GATT) and Section 201 of U.S. trade law. This provision, which permits temporary tariffs to be applied, is used infrequently. As shown in Table 9-1, from 1980 to 1989, only 19 safeguard (also called “escape clause”) cases were filed in the United States. In the following decade there were only nine, and from 2000 to 2011 only three such cases were filed. In each case, the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) must determine whether rising imports are the “most important cause of serious injury, or threat thereof, to the domestic industry.” Of the 31 cases filed from 1980 to 2011, the ITC made a negative recommendation (i.e., it did not approve the tariff requests) in 16, or about one-half the cases. One of those negative recommendations was for the tariff on Japanese compact trucks discussed in the earlier application: the ITC made a negative recommendation for both cars and trucks in 1980, but trucks still obtained a tariff by reclassifying the type of trucks being imported.

303

The ITC made an affirmative ruling for protection in 12 cases, which then went for a final ruling to the President, who recommended import protection in only nine cases.13 An example of a positive recommendation was the tariff on the import of steel, as discussed in the previous chapter, and the tariff imposed on heavyweight motorcycles, discussed later in this chapter. That only 31 cases were brought forward in three decades, and that tariffs were approved by the President in only nine cases, shows how infrequently this trade provision is used.

In the next panel of Table 9-1, we show the number of China-specific safeguard cases. This new trade provision, discussed in the previous chapter, took effect in 2001. Since that time, seven cases have been filed, of which two were denied by the ITC and five were approved. Of these five approved tariffs, the President also ruled in favor only once—the tariff imposed on imports of tires from China, approved by President Obama in 2009 and in effect until 2012.

304

The infrequent use of the safeguard provision can be contrasted with the many cases of antidumping duties. The cases filed in the United States under this provision are also listed in Table 9-1, which shows that the number of antidumping cases vastly exceeds safeguard cases. From 1980 to 1989 and from 1990 to 1999, there were more than 400 antidumping cases filed in the United States. In the next 12 years, 2000 to 2011, there were more than 300 antidumping cases, bringing the total number of antidumping cases filed from 1980 to 2011 to more than 1,200!

To have antidumping duties applied, a case must first go to the U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC), which rules on whether imports are selling domestically at “less than fair value”; that is, below the price in their own market or below the average cost of making them. These rulings were positive in 93% of cases during this period. The case is then brought before the ITC, which must rule on whether imports have caused “material injury” to the domestic industry (defined as “harm that is not inconsequential, immaterial, or unimportant”). This criterion is much easier to meet than the “substantial cause of serious injury” provision for a safeguard tariff, and as a result, the ITC more frequently rules in favor of antidumping duties. Furthermore, the application of duties does not require the additional approval of the President. Of the 1,200 antidumping cases filed from 1980 to 2011, about 450 were rejected and another 550 had duties levied.

The remaining 150 antidumping cases (or 148 to be precise, shown at the bottom of Table 9-1) fall into a surprising third category: those that are withdrawn prior to a ruling by the ITC. It turns out that the U.S. antidumping law actually permits U.S. firms to withdraw their case and, acting through an intermediary at the DOC, agree with the foreign firm on the level of prices and market shares! As we would expect, these withdrawn and settled cases result in a significant increase in market prices for the importing country.

Why do firms make claims of dumping so often? If a dumping case is successful, a duty will be applied against the Foreign competitor, and the import price will increase. If the case is withdrawn and settled, then the Foreign competitor will also raise its price. Even if the case is not successful, imports often decline while the DOC or ITC is making an investigation, and the smaller quantity of imports also causes their price to rise. So regardless of the outcome of a dumping case, the increase in the price of Foreign imports benefits Home firms by allowing them to charge more for their own goods. As a result, Home producers have a strong incentive to file for protection from dumping, whether it is occurring or not.

Because of the large number of antidumping cases and because exporting firms raise their prices to avoid the antidumping duties, this trade policy can be quite costly. According to one estimate, the annual cost to the United States from its antidumping policies is equivalent to the deadweight loss of a 6% uniform tariff applied across all imports.14

An interesting fact . . .

. . . and its explanation.