5 Infant Industry Protection

Suppose that increasing production today reduces costs in the future. Should the government intervene to protect an industry today so that it can profit in the future? Yes, in two cases: (1) if increased production today raises productivity, and if the firm is unable to borrow to cover its initial losses; (2) if increased production today confers positive externalities that reduce costs of other firms. Both cases require market failure: In (1) imperfect capital markets and in (2) an externality.

1. Free-Trade Equilibrium

Domestic monopolist exports to a competitive world market. It has high costs today, but lower costs in the future.

a. Equilibrium Today

Since AC > P, the firm would not produce today.

2. Tariff Equilibrium

To protect the industry, the government could impose a tariff or quota. The tariff is more efficient.

a. Equilibrium Today

Assume tariff is set so the firm breaks even today.

b. Equilibrium in the Future

Costs fall in the future, so that the firm can operate without the tariff.

c. Effect of the Tariff on Welfare

There is the usual deadweight loss today, but an increase in producer surplus in the future. The tariff makes sense if the current deadweight loss is less than the present value of the future gain in producer surplus.

We now turn to the final application of tariffs that we will study in this chapter, and that is a tariff applied to an industry that is too young to withstand foreign competition, and so will suffer losses when faced with world prices under free trade. Given time to grow and mature, the industry will be able to compete in the future. The only way that a firm in this industry could cover its losses today would be to borrow against its future profits. But if banks are not willing to lend to this firm—perhaps because it is small and inexperienced—then it will go bankrupt today unless the government steps in and offers some form of assistance, such as with a tariff or quota. This argument is called the “infant industry case” for protection. Although we include the infant industry tariff argument in this chapter on strategic trade policy, the idea of protecting a young industry dates back to the writings of John Stuart Mill (1806–1873).

305

To analyze this argument and make use of our results from the previous sections, we assume there is only one Home firm, so it is again a case of Home monopoly. The special feature of this Home firm is that increasing its output today will lead to lower costs in the future because it will learn how to produce its output more efficiently and at a lower cost. The question, then, is whether the Home government should intervene with a temporary protective tariff or quota today, so that the firm can survive long enough to achieve lower costs and higher profits in the future.

There are two cases in which infant industry protection is potentially justified. First, protection may be justified if a tariff today leads to an increase in Home output that, in turn, helps the firm learn better production techniques and reduce costs in the future. This is different from increasing returns to scale as discussed in Chapter 6. With increasing returns to scale, lower costs arise from producing farther down along a decreasing average cost curve; while a tariff might boost Home production and lower costs, removing the tariff would reduce production to its initial level and still leave the firm uncompetitive at world prices. For infant industry protection to be justified, the firm’s learning must shift down the entire average cost curve to the point where it is competitive at world prices in the future, even without the tariff.

If the firm’s costs are going to fall in the future, then why doesn’t it simply borrow today to cover its losses and pay back the loan from future profits? Why does it need import protection to offset its current losses? The answer was already hinted at above: banks may be unwilling to lend to this firm because they don’t know with certainty that the firm will achieve lower costs and be profitable enough in the future to repay the loan. In such a situation, a tariff or quota offsets an imperfection in the market for borrowing and lending (the capital market). What is most essential for the infant industry argument to be valid is not imperfect competition (a single Home firm), but rather, this imperfection in the Home capital market.

A second case in which import protection is potentially justified is when a tariff in one period leads to an increase in output and reductions in future costs for other firms in the industry, or even for firms in other industries. This type of externality occurs when firms learn from each other’s successes. For instance, consider the high-tech semiconductor industry. Each firm innovates its products at a different pace, and when one firm has a technological breakthrough, other firms benefit by being able to copy the newly developed knowledge. In the semiconductor industry, it is not unusual for firms to mimic the successful innovations of other firms, and benefit from a knowledge spillover. In the presence of spillovers, the infant industry tariff promotes a positive externality: an increase in output for one firm lowers the costs for everyone. Because firms learn from one another, each firm on its own does not have much incentive to invest in learning by increasing its production today. In this case, a tariff is needed to offset this externality by increasing production, allowing for these spillovers to occur among firms so that there are cost reductions.

306

Students often come into this question presuming naively that of course we should nurture our infant industries, so emphasize this.

As both of these cases show, the infant industry argument supporting tariffs or quotas depends on the existence of some form of market failure. In our first example, the market does not provide loans to the firm to allow it to avoid bankruptcy; in the second, the firm may find it difficult to protect its intellectual knowledge through patents, which would enable it to be compensated for the spillover of knowledge to others. These market failures create a potential role for government policy. In practice, however, it can be very difficult for a government to correct market failure. If the capital market will not provide loans to a firm because it doesn’t think the firm will be profitable in the future, then why would the government have better information about that firm’s future prospects? Likewise, in the case of a spillover of knowledge to other firms, we cannot expect the government to know the extent of spillovers. Thus, we should be skeptical about the ability of government to distinguish the industries that deserve infant industry protection from those that do not.

as well as emphasizing this...

Furthermore, even if either of the two conditions we have identified to potentially justify infant industry protection hold, these market failures do not guarantee that the protection will be worthwhile—we still need to compare the future benefits of protection (which are positive) with its costs today (the deadweight losses). So while some form of market failure is a prerequisite condition for infant industry protection to be justified, we will identify two further conditions below that must be satisfied for the protection to be successful. With these warnings in mind, let’s look at how infant industry protection can work.

Free-Trade Equilibrium

Key assumption

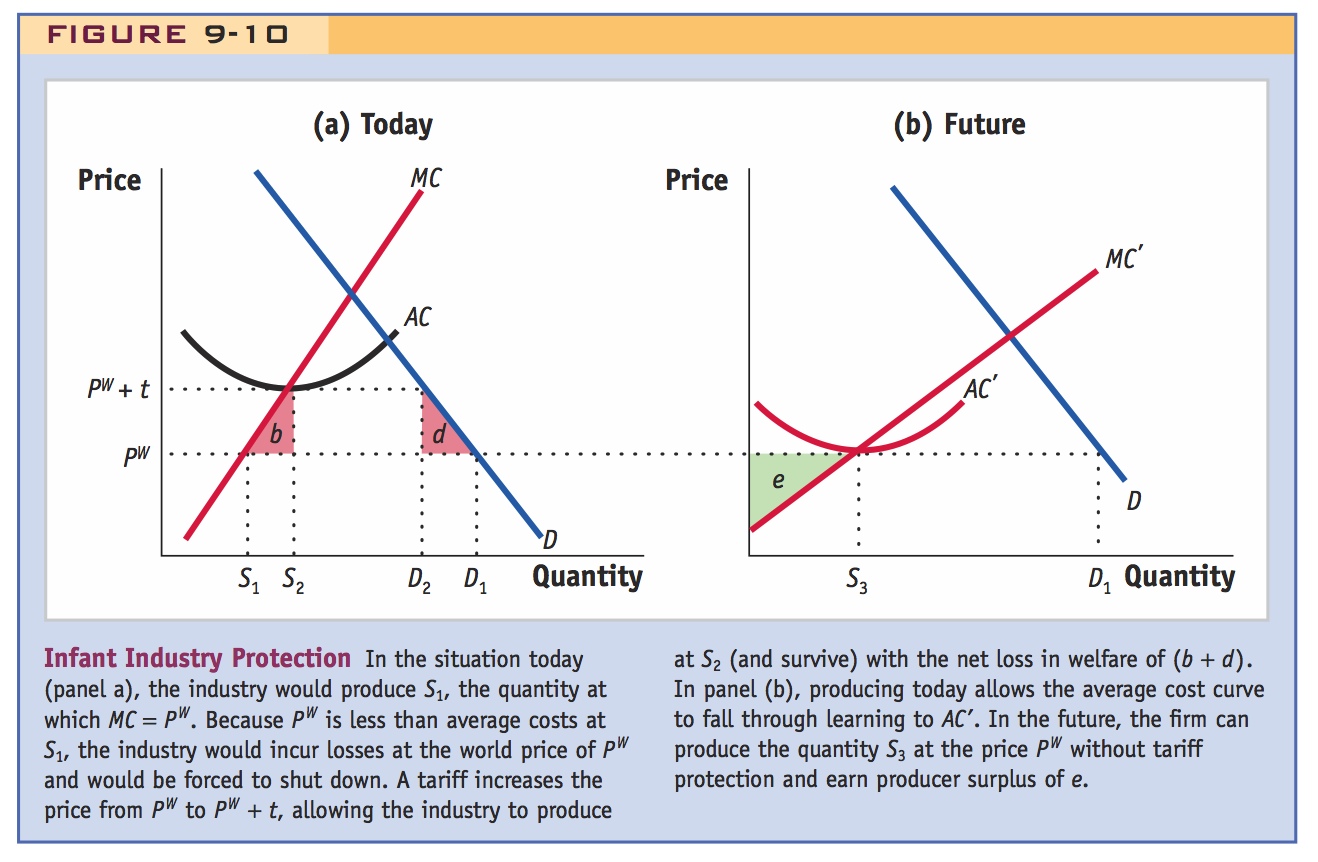

In panel (a) of Figure 9-10, we show the situation a Home firm faces today, and in panel (b) we show its situation in the future. We assume that the Home country is small and therefore faces a fixed world price. As discussed earlier in the chapter, even a Home monopolist will behave in the same manner as a perfectly competitive industry under free trade, assuming that they have the same marginal costs. We also assume that any increase in the firm’s output today leads to a reduction in costs in the future (i.e., a downward shift in the firm’s average cost curve).

Equilibrium Today With free trade today, the Home firm faces the world price of PW (which, you will recall from earlier in this chapter, is also its marginal revenue curve) and will produce to the point at which its marginal cost of production equals PW. The Home firm therefore supplies the quantity S1. To verify that S1 is actually the Home supply, however, we need to check that profits are not negative at this quantity. To do so, we compare the firm’s average costs with the price. The average cost curve is shown as AC in panel (a), and at the supply of S1, average costs are much higher than the price PW. That means the Home firm is suffering losses and would shut down today instead of producing S1.

Tariff Equilibrium

To prevent the firm from shutting down, the Home government could apply an import tariff or quota to raise the Home price. Provided that the Home firm increases its output in response to this higher price, we assume that this increased size allows the firm to learn better production techniques so that its future costs are reduced. Given the choice of an import tariff or quota to achieve this goal, the Home government should definitely choose the tariff. The reason is that when a Home monopolist is faced with a quota rather than a tariff, it will produce less output under the quota so that it can further raise its price. The decrease in output leads to additional deadweight loss today, as discussed earlier in the chapter. Furthermore, because we have assumed that the firm’s learning depends on how much it produces and output is lower under the quota, there would be less learning and a smaller reduction in future costs under a quota than a tariff. For both reasons, a tariff is a better policy than a quota when the goal is to nurture an infant industry.

307

Equilibrium Today If the government applies an import tariff of t dollars today, the Home price increases from PW to PW + t. We assume that the government sets the tariff high enough so that the new Home price, PW + t, just covers the infant industry’s average costs of production. At this new price, the firm produces the quantity S2 in panel (a). As illustrated, the price PW + t exactly equals average costs, AC, at the quantity S2, so the firm is making zero profits. Making zero profits means that the Home firm will continue to operate.

Condition 1: The fall in cost must be large enough for the industry to stay in business in the future without the tariff.

Equilibrium in the Future With the firm producing S2 today rather than S1, it can learn about better production methods and lower its costs in the future. The effect of learning on production costs is shown by the downward shift of the average cost curve from AC in panel (a) to AC′ in panel (b).15 The lower average costs in the future mean that the firm can produce quantity S3 without tariff protection at the world price PW in panel (b) and still cover its average costs. We are assuming that the downward shift in the average cost curve is large enough that the firm can avoid losses at the world price PW. If that is not the case—if the average cost curve AC′ in panel (b) is above the world price PW—then the firm would be unable to avoid losses in the future and the infant industry protection would not be successful. But if the temporary tariff today allows the firm to operate in the future without the tariff, then the infant industry protection has satisfied the first condition to be judged successful.

308

Effect of the Tariff on Welfare The application of the tariff today leads to a deadweight loss, and in panel (a), the deadweight loss is measured by the triangles (b + d). But we also need to count the gain from having the firm operating in the future. In panel (b) of Figure 9-10, the producer surplus earned in the future by the firm is shown by the region e. We should think of the region e as the present value (i.e., the discounted sum over time) of the firm’s future producer surplus; it is this amount that would be forgone if the firm shut down today. The second condition for the infant industry protection to be successful is that the deadweight loss (b + d) when the tariff is used should be less than the area e, which is present value of the firm’s future produce surplus when it no longer needs the tariff.

Condition 2: The current costs of the tariff must be less than (presumably the present value) of the future benefits.

To evaluate whether the tariff has been successful, it needs to satisfy both conditions: the firm has to be able to produce without losses and without needing the tariff in the future; and the future gains in producer surplus need to exceed the current deadweight loss from the tariff. To evaluate the second criterion, we need to compare the future gain of e with the deadweight loss today of (b + d). If e exceeds (b + d), then the infant industry protection has been worthwhile, but if e is less than (b + d), then the costs of protection today do not justify the future benefits. The challenge for government policy is to try to distinguish worthwhile cases (those for which future benefits exceed present costs) from those cases that are not. In the application that follows, we will see whether the governments of China, Brazil, and the United States have been able to distinguish between these cases.

Four detailed studies of infant industry protection: (1) solar panels in U.S., Europe, and China; (2) U.S. tariffs for Harley-Davidson, (3) computer imports in Brazil; (4) protection for autos in China

Examples of Infant Industry Protection

There are many examples of infant industry protection in practice, and we will consider four: (1) policies used in the United States, Europe, and in China to support the solar panel industry; (2) a U.S. tariff imposed to protect Harley-Davidson motorcycles in the United States during the 1980s; (3) a complete ban on imports imposed from 1977 to the early 1990s to protect the computer industry in Brazil; and (4) tariffs and quotas imposed to protect the automobile industry in China, which were reduced when China joined the WTO in 2001.

Government Policies in the Solar Panel Industry

Many countries subsidize the production or installation of photovoltaic cells (solar panels). In the United States, there are tax credits available to consumers who install solar panels on their home. This type of policy is common in other countries, too, and can be justified because the generation of electricity using solar panels does not lead to any pollution, in contrast to the generation of electricity by the burning of fossil fuels (coal, natural gas, and oil), which emits carbon dioxide and other pollutants. Earlier in this chapter we introduced the concept of an externality, which is an economic activity that imposes costs on other firms or consumers. Pollution is the leading example of an externality, and too much pollution will be emitted unless the government takes some action. Giving a subsidy to users of solar panels, because these households and businesses use less electricity from fossil fuels, is one way to limit the amount of pollution arising from electricity generation.

309

the market failure on this case

But how can we assess future benefits?

So subsidies for the use of solar panels are a way to correct an externality and, on their own, should not be viewed as a form of infant industry protection. But countries use other policies to encourage the production (not just the use) of solar panels in their own country. In the United States, the government gives tax breaks and low-interest loans or loan guarantees to companies that produce solar panels. One example of a loan guarantee was to the U.S. company Solyndra, which received a $535 million loan guarantee from the U.S. Department of Energy in 2009. The guarantee meant that the U.S. government would repay the loan if Solyndra could not, so that banks making loans to Solyndra did not face any risk. That policy can be viewed as a type of infant industry protection: giving the loan guarantee in the hope that the company will be profitable in the future. But Solyndra subsequently went bankrupt in 2011, and President Obama was widely criticized for this loan guarantee. This example illustrates how difficult it is to know whether a company protected by some form of infant industry protection will actually become profitable in the future, which is one of the conditions for the infant industry protection to be successful.

China has also pursued policies to encourage the production of solar panels, and especially to encourage their export. We discussed the use of export subsidies in China in an earlier application dealing with U.S. imports of solar panels from China. We discuss export subsidies in more detail in the next chapter, but for now you should think of them as similar to import tariffs: the export subsidy raises the price received by firms, just like an import tariff, and also carries a deadweight loss. So our discussion of infant industry protection applies equally well to export subsidies: these infant-industry policies are successful if (1) the industry becomes profitable in the future, after the export subsidy is removed; and (2) the deadweight loss of the subsidy is less than the future profits earned by the industry.

As we have already learned about the use of loan guarantees in the United States (where Solyndra went bankrupt), export subsidies also don’t always work out as planned. In China, for example, the extensive use of subsidies led to vast overcapacity in the industry, which in turn led to the bankruptcy of the key Chinese firm, Suntech Power Holdings, whose main subsidiary in Beijing went bankrupt in March 2013. The Suntech-affiliated firms were named in the antidumping and countervailing duty case brought by the American companies in 2011 as having the lowest prices in the United States. The fact that some of these firms have gone bankrupt indicates that the Chinese export subsidies were not successful in leading them to be profitable. Other firms have survived and are still producing in China, but their exports to the United States are limited by the antidumping and countervailing duties now applied by the United States. Furthermore, the European Union is now contemplating stiff antidumping penalties against Chinese firms, as discussed in Headlines: Solar Flares. Ironically, the company in Europe calling for these duties is SolarWorld, whose U.S. subsidiary filed the trade case against Chinese exporters of solar panels in the United States. If these European duties are enacted, more Chinese firms could go bankrupt. For these various reasons, it appears that the Chinese subsidies to the solar panel industry have not been successful.

310

Still, we should recognize that this industry is still young and future years could bring further changes. Some experts believe that the industry might now migrate to Taiwan, where it would not face the U.S. tariffs applied against China. On the other hand, the Chinese industry itself will be helped by subsidies to the installation of solar panels in China, which the government is now starting to use rather than only relying on export subsidies. And in the United States and Europe, there are still a number of producers of solar panels, as well as a strong industry involved with the installation of either locally produced or imported panels, and this industry will continue to create demand for solar panels built in China or elsewhere in Asia. Given the state of the worldwide solar panel industry, it is too early to say for sure what the long-term impact of the U.S., European, and Chinese policies will be.

U.S. Tariff on Heavyweight Motorcycles

Harley-Davidson does not really fit the usual description of an “infant” industry: the first plant opened in 1903 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and it was owned and operated by William Harley and the three Davidson brothers. Until the late 1970s it did not face intense import competition from Japanese producers; but by the early 1980s, Harley-Davidson was on the verge of bankruptcy. Even though it had been around since 1903, Harley-Davidson had many of the characteristics we associate with an infant industry: the inability to compete at the international price today and (as we will see) the potential for lower costs in the future. By including this case in our discussion of infant industries, we are able to make a precise calculation of the effect of the tariffs on consumers and producers to determine whether the infant industry protection was successful.

European proposal to impose antidumping duties on Chinese solar panels

Solar Flares

This article discusses the solar energy industry in Europe, and a recent proposal by the European Union to impose antidumping duties against China.

Four years ago, in the midst of Europe’s solar energy boom, Wacker Chemie opened a new polysilicon factory in its sprawling chemicals facility in the small Bavarian town of Burghausen. There, in a production hall as large as an aircraft hangar but as clean as a laboratory, ultra-pure ingots of polysilicon—the most basic ingredient in photovoltaic cells—take shape in custom-built reactors heated to more than 1,000C. These days, the boom is over and Wacker’s factory, with its 2,400 workers, is looking vulnerable. The company has been caught in what is shaping up to be a decisive trade fight between Europe and China and Wacker executives are worried about collateral damage.

Last September the EU launched its biggest ever investigation, probing billions of euros of imports of Chinese solar equipment. This week Karel De Gucht, the EU trade commissioner, urged that provisional duties averaging 47 per cent be imposed on the country’s exports of solar panels for dumping, or selling products below cost, in Europe. For Wacker, the fear is that such measures will backfire by pushing up solar equipment prices for consumers and further undermining an industry already under pressure in Europe. Adding to their unease is the likelihood that Wacker will be first in line for Chinese retaliation. Late last year—just weeks after the EU opened its investigation—Beijing launched its own probe into Europe’s polysilicon manufacturers. “This simply does not make sense,” says Rudolf Staudigl, Wacker’s chief executive, who is pleading with Brussels to hold fire. “If tariffs are implemented, Europe will be damaged more than China.”

The case has risen to the highest political levels, with Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, last year calling for a negotiated solution amid concerns that the confrontation could precipitate a full-blown trade war.

Source: Excerpted from “Solar Flares,” Main Paper, May 10, 2013, p. 7. From the Financial Times © The Financial Times Limited 2013. All Rights Reserved.

311

In 1983 Harley-Davidson, the legendary U.S.-based motorcycle manufacturer, was in trouble. It was suffering losses due to a long period of lagging productivity combined with intense competition from Japanese producers. Two of these producers, Honda and Kawasaki, not only had plants in the United States but also exported Japan-made goods to the United States. Two other Japanese producers, Suzuki and Yamaha, produced and exported their products from Japan. In the early 1980s these four Japanese firms were engaged in a global price war that spilled over into the U.S. market, and inventories of imported heavyweight cycles rose dramatically in the United States. Facing this intense import competition, Harley-Davidson applied to the International Trade Commission (ITC) for Section 201 protection.

As required by law, the ITC engaged in a study to determine the source of injury to the industry, which in this case was identified as heavyweight (more than 700 cc) motorcycles. Among other factors, it studied the buildup of inventories by Japanese producers in the United States. The ITC determined that there was more than nine months’ worth of inventory of Japanese motorcycles already in the United States, which could depress the prices of heavyweight cycles and threaten bankruptcy for Harley-Davidson. As a result, the ITC recommended to President Ronald Reagan that import protection be placed on imports of heavyweight motorcycles. This case is interesting because it is one of the few times that the threat of injury by imports has been used as a justification for tariffs under Section 201 of U.S. trade law.

President Reagan approved the recommendation from the ITC, and tariffs were imposed on imports of heavyweight motorcycles. These tariffs were initially very high, but they declined over five years. The initial tariff, imposed on April 16, 1983, was 45%; it then fell annually to 35%, 20%, 15%, and 10% and was scheduled to end in April 1988. In fact, Harley-Davidson petitioned the ITC to end the tariff one year early, after the 15% rate expired in 1987, by which time it had cut costs and introduced new and very popular products so that profitability had been restored. Amid great fanfare, President Reagan visited the Harley-Davidson plant in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and declared that the tariff had been a successful case of protection.

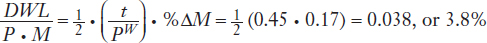

Calculation of Deadweight Loss Was the tariff on heavyweight motorcycles really successful? To answer this, we need to compare the deadweight loss of the tariff with the future gain in producer surplus. In our discussion of the steel tariff in the previous chapter, we derived a formula for the deadweight loss from using a tariff, measured relative to the import value:

We can calculate the average import sales from 1982 to 1983 as (452 + 410)/2 = $431 million. Multiplying the percentage loss by average imports, we obtain the deadweight loss in 1983 of 0.038 × 431 = $16.3 million. That deadweight loss is reported in the last column of Table 9-2, along with the loss for each following year. Adding up these deadweight losses, we obtain a total loss of $112.5 million over the four years that the tariff was used.16

312

Future Gain in Producer Surplus To judge whether the tariff was effective, we need to compare the deadweight loss of $112.5 million with the future gain in producer surplus (area e in Figure 9-10). How can we assess these future gains? We can use a technique that economists favor: we can evaluate the future gains in producer surplus by examining the stock market value of the firm around the time that the tariff was removed.

During the time that the tariff was in place, the management of Harley-Davidson reduced costs through several methods: implementing a “just-in-time” inventory system, which means producing inventory on demand rather than having excess amounts in warehouses; reducing the workforce (and its wages); and implementing “quality circles,” groups of assembly workers who volunteer to meet together to discuss workplace improvements, along with a “statistical operator control system” that allowed employees to evaluate the quality of their output. Many of these production techniques were copied from Japanese firms. The company also introduced a new engine. These changes allowed Harley-Davidson to transform losses during the period from 1981 to 1982 into profits for 1983 and in following years.

In July 1986 Harley-Davidson became a public corporation and issued stock on the American Stock Exchange: 2 million shares at $11 per share, for a total offering of $22 million. It also issued debt of $70 million, which was to be repaid from future profits. In June 1987 it issued stock again: 1.23 million shares at $16.50 per share, for a total offering of $20.3 million. The sum of these stock and debt issues is $112.3 million, which we can interpret as the present discounted value of the producer surplus of the firm. This estimate of area e is nearly equal to the consumer surplus loss, $112.5 million, in Table 9-2. Within a month after the second stock offering, however, the stock price rose from $16.50 to $19 per share. Using that price to evaluate the outstanding stock of 3.23 million, we obtain a stock value of $61 million, plus $70 million in repaid debt, to obtain $131 million as the future producer surplus.

313

But where was the market failure?

By this calculation, the future gain in producer surplus from tariff protection to Harley-Davidson ($131 million) exceeds the deadweight loss of the tariff ($112.5 million). Furthermore, since 1987 Harley-Davidson has become an even more successful company. Its sales and profits have grown every year, and many model changes have been introduced, so it is now the Japanese companies that copy Harley-Davidson. By March 2005 Harley-Davidson had actually surpassed General Motors in its stock market value: $17.7 billion versus $16.2 billion. Both of these companies suffered losses during the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009, but Harley-Davidson continued to operate as usual (with a stock market value of $4.3 billion in mid-2009), whereas General Motors declared bankruptcy and required a government bailout (its stock market value fell to less than $0.5 billion). Although both companies can be expected to recover after the crisis, it is clear that General Motors—which once had the world’s highest stock market value—has been surpassed by Harley-Davidson.

Was Protection Successful? Does this calculation mean that the infant industry protection was successful? A complete answer to that question involves knowing what would have happened if the tariff had not been put in place. When we say that infant industry protection is successful if the area e of future producer surplus gain ($131 million) exceeds the deadweight loss ($112.5 million), we are assuming that the firm would not have survived at all without the tariff protection. That assumption may be true for Harley-Davidson. It is well documented that Harley-Davidson was on the brink of bankruptcy from 1982 to 1983. Citibank had decided that it would not extend more loans to cover Harley’s losses, and Harley found alternative financing on December 31, 1985, just one week before filing for bankruptcy.17 If the tariff saved the company, then this was clearly a case of successful infant industry protection.

On the other hand, even if Harley-Davidson had not received the tariff and had filed for bankruptcy, it might still have emerged to prosper again. Bankruptcy does not mean that a firm stops producing; it just means that the firm’s assets are used to repay all possible debts. Even if Harley-Davidson had gone bankrupt without the tariff, some or all of the future gains in producer surplus might have been realized. So we cannot be certain whether the turnaround of Harley-Davidson required the use of the tariff.18

But the fact that HD couldn't get a loan didn't mean there was a capital market imperfection, merely that lenders were less sanguine about its prospects than the government implicitly was.

Despite all these uncertainties, it still appears that the tariff on heavyweight motorcycles bought Harley-Davidson some breathing room. This is the view expressed by the chief economist at the ITC at that time, in the quotation at the beginning of the chapter: “If the case of heavyweight motorcycles is to be considered the only successful escape-clause [tariff], it is because it caused little harm and it helped Harley-Davidson get a bank loan so it could diversify.”19 We agree with this assessment that the harm caused by the tariff was small compared with the potential benefits of avoiding bankruptcy, which allowed Harley-Davidson to become the very successful company that it is today.

314

Computers in Brazil

There are many cases in which infant industry protection has not been successful. One well-known case involves the computer industry in Brazil. In 1977 the Brazilian government began a program to protect domestic firms involved in the production of personal computers (PCs). It was thought that achieving national autonomy in the computer industry was essential for strategic military reasons. Not only were imports of PCs banned, but domestic firms also had to buy from local suppliers whenever possible, and foreign producers of PCs were not allowed to operate in Brazil.

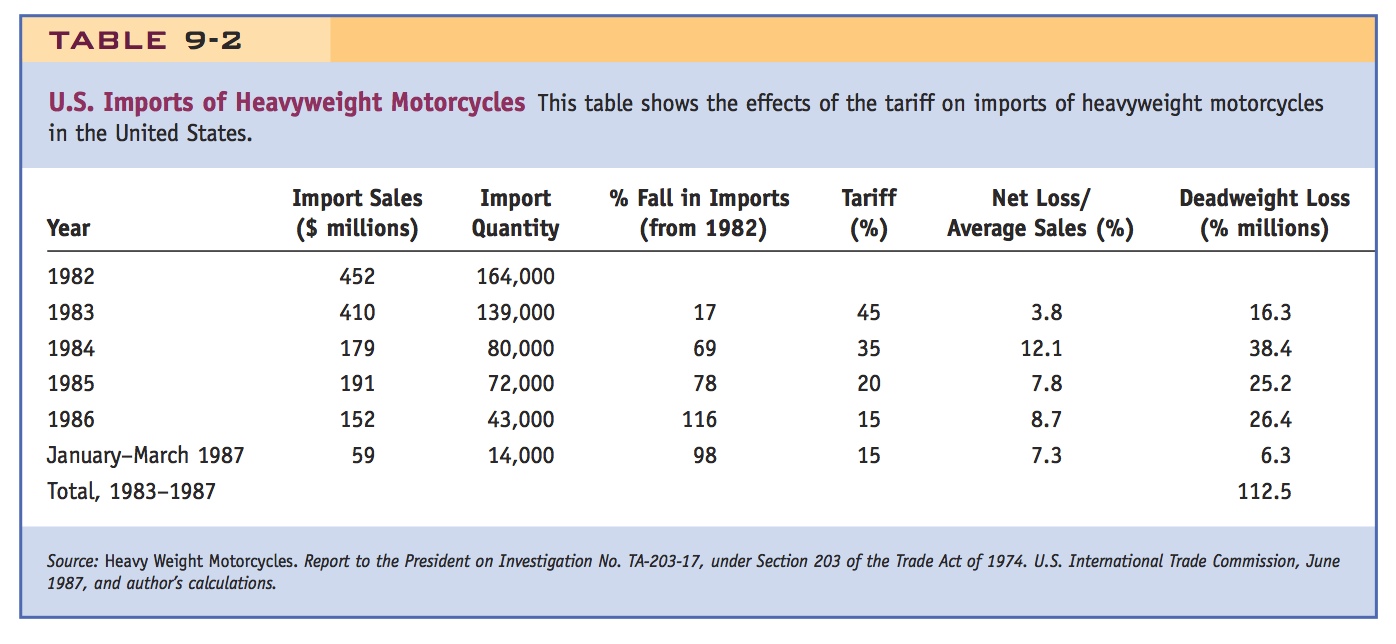

Prices in Brazil The Brazilian ban on imports lasted from 1977 to the early 1990s. This was a period of rapid innovations in PC production worldwide, with large drops in the cost of computing power. In Figure 9-11, we show the effective price of computing power in the United States and Brazil between 1982 and 1992, which fell very rapidly in both countries. The price we are graphing is “effective” because it is not just the retail price of a new PC but a price index that reflects the improvements over time in the PC’s speed of calculations, storage capacity, and so on.

315

Brazilian firms were adept at reverse engineering the IBM PCs being sold from the United States. But the reverse engineering took time, and the fact that Brazilian firms were required to use local suppliers for many parts within the computers added to the costs of production. We can see from Figure 9-11 that Brazil never achieved the same low prices as the United States. By 1992, for example, the effective prices in Brazil were between the prices that had been achieved in the United States four or five years earlier. The persistent gap between the prices in Brazil and the United States means that Brazil was never able to produce computers at competitive prices without tariff protection. This fact alone means that the infant industry protection was not successful.

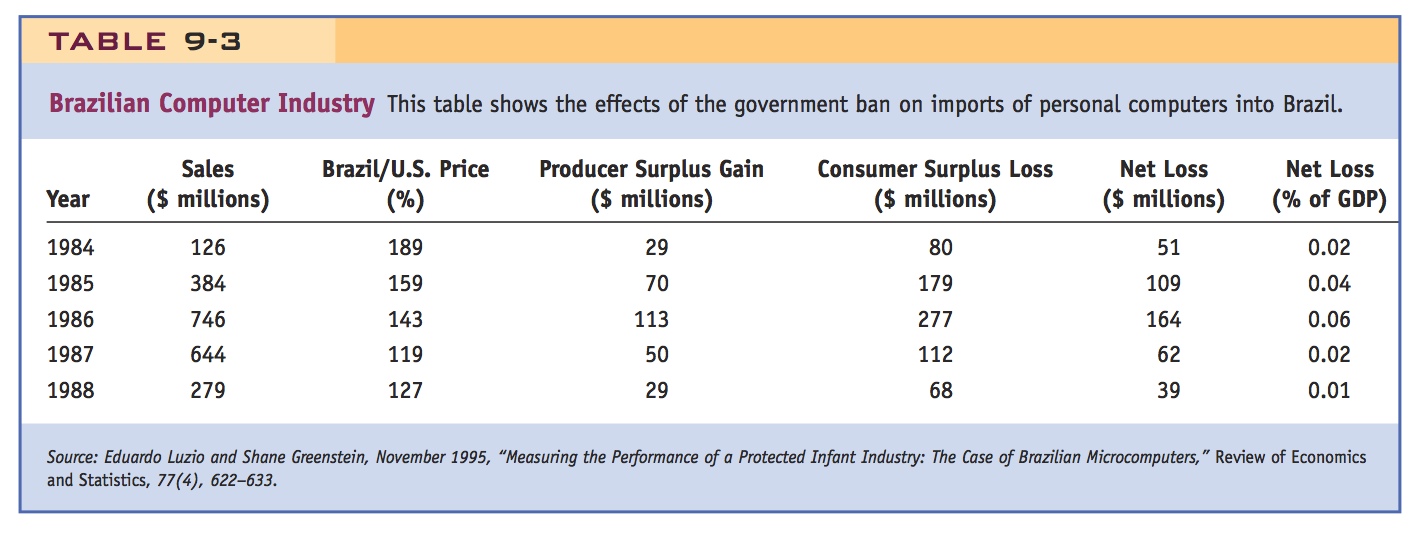

Consumer and Producer Surplus In Table 9-3, we show the welfare calculation for Brazil, as well as other details of the PC industry. Local sales peaked at about $750 million in 1986, and the following year, the Brazilian prices rose to within 20% of those in the United States. But that is as close as the Brazilian industry ever got to world prices. In 1984 prices in Brazil were nearly double those in the United States, which led to a producer surplus gain of $29 million but a consumer surplus loss in Brazil of $80 million. The net loss was therefore $80 million − $29 million = $51 million, which was 0.02% of Brazilian gross domestic product (GDP) that year. By 1986 the net loss had grown to $164 million, or 0.06% of GDP. This net loss was the deadweight loss from the tariff during the years it was in place. The industry was never able to produce in the absence of tariffs, so there are no future gains (like area e in Figure 9-10) that we can count against those losses.

Other Losses The higher prices in Brazil imposed costs on Brazilian industries that relied on computers in manufacturing, as well as on individual users, and they became increasingly dissatisfied with the government’s policy. During his campaign in 1990, President Fernando Collor de Mello promised to abolish the infant industry protection for personal computers, which he did immediately after he was elected.

A number of reasons have been given for the failure of this policy to develop an efficient industry in Brazil: imported materials such as silicon chips were expensive to obtain, as were domestically produced parts that local firms were required to use; in addition, local regulations limited the entry of new firms into the industry. Whatever the reasons, this case illustrates how difficult it is to successfully nurture an infant industry and how difficult it is for the government to know whether temporary protection will allow an industry to survive in the future.

316

Protecting the Automobile Industry in China

The final example of infant industry protection that we discuss involves the automobile industry in China. In 2009, China overtook the United States as the largest automobile market in the world (measured by domestic sales plus imports). Strong competition among foreign firms located in China, local producers, and import sales have resulted in new models and falling prices so that the Chinese middle class can now afford to buy automobiles. In 2009, there were over 13 million vehicles sold in China, as compared with 10.4 million cars and light trucks sold in the United States. Four years later in 2013, the Chinese industry is poised to reach another milestone by producing more cars than Europe, as described in Headlines: Milestone for China Car Output.

Documents rapid expansion of Chinese car production

Milestone for China Car Output

China is poised to produce more cars than Europe in 2013 for the first time, hitting a landmark in the country’s rise in the automobile industry and underlining the difficulties for the European vehicle sector as it faces a challenging 12 months. China is in 2013 set to make 19.6 million cars and other light vehicles such as small trucks compared with 18.3 million in Europe…In 2012, on the basis of motor industry estimates, Europe made 18.9 million cars and related vehicles, comfortably ahead of China’s tally of 17.8 million…. With global sales valued at about $1.3 trillion a year, the car industry is one of the best bellwethers of world economic conditions.

According to the data, Europe will in 2013 make just over a fifth of the world’s cars—a figure that is well down on the 35 per cent it recorded in 2001. In 1970 nearly one in every two cars made in the world originated from a factory in Europe—which is generally recognized as the place where the global auto industry began with the unveiling of a rudimentary three-wheeler in 1885 by the German inventor Karl Benz. Car production in China in 2013 is likely to be 10 times higher than in 2000—when its share of global auto manufacturing was just 3.5 per cent as opposed to a likely 23.8 per cent in 2013.

Source: Excerpted from “Milestone for China Car Output,” Financial Times, January 2, 2013, p. 11. From the Financial Times © The Financial Times Limited 2013. All Rights Reserved.

Growth in automotive production and sales has been particularly strong since 2001, when China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO). With its accession to the WTO, China agreed to reduce its tariffs on foreign autos, which were as high as 260% in the early 1980s, then fell from 80% to 100% by 1996, and 25% by July 2006. The tariff on automobile parts was further cut from 25% to 10% in 2009. China has loosened its import quotas, as well. Those tariffs and quotas, in addition to restrictions at the province and city level on what type of cars could be sold, had limited China’s imports and put a damper on the auto industry in that country. Prices were high and foreign producers were reluctant to sell their newest models to China. That situation has changed dramatically. Now, foreign firms scramble to compete in China with their latest designs and are even making plans to export cars from China. Is the Chinese automobile industry a successful case of infant industry protection? Are the benefits gained by the current production and export of cars greater than the costs of the tariffs and quotas imposed in the past? To answer this, we begin by briefly describing the history of the Chinese auto industry.

317

Production in China Beginning in the early 1980s, China permitted a number of joint ventures between foreign firms and local Chinese partners. The first of these in 1983 was Beijing Jeep, which was a joint venture between American Motors Corporation (AMC—later acquired by Chrysler Corporation) and a local firm in Beijing. The following year, Germany’s Volkswagen signed a 25-year contract to make passenger cars in Shanghai, and France’s Peugeot agreed to another passenger car project to make vehicles in Guangzhou.

Although joint venture agreements provided a window for foreign manufacturers to tap the China market, there were limits on their participation. Foreign manufacturers could not own a majority stake in a manufacturing plant—Volkswagen’s venture took the maximum of 50% foreign ownership. The Chinese also kept control of distribution networks for the jointly produced automobiles. These various regulations, combined with high tariff duties, helped at least some of the new joint ventures achieve success. Volkswagen’s Shanghai plant was by the far the winner under these rules, and it produced more than 200,000 vehicles per year by the late 1990s, more than twice as many as any other plant. Volkswagen’s success was also aided by some Shanghai municipal efforts. Various restrictions on engine size, as well as incentives offered to city taxi companies that bought Volkswagens, helped ensure that only Volkswagen’s models could be sold in the Shanghai market; essentially, the Shanghai Volkswagen plant had a local monopoly.

That local monopoly has been eroded by entry into the Shanghai market, however. A recent example occurred in early 2009, when General Motors opened two new plants in Shanghai, at a cost of $1.5 billion and $2.5 billion each. General Motors is a leading producer in China, and locally produced 1.8 million of the 13 million vehicles sold in China in 2009. In fact, its profits from the Chinese market were the only bright spot on its global balance sheet that year, and served to offset some of its losses in the American market, as described in Headlines: Shanghai Tie-Up Drives Profits for GM.

Cost to Consumers The tariffs and quotas used in China kept imports fairly low throughout the 1990s, ranging from a high of 222,000 cars imported in 1993 to a low of 27,500 imports in 1998 and 160,000 cars in 2005. Since tariffs were in the range of 80% to 100% by 1996, import prices were approximately doubled because of the tariffs. But the quotas imposed on auto imports probably had at least as great an impact on prices of imports and domestically produced cars. Our analysis earlier in the chapter showed that quotas have a particularly large impact on domestic prices when the Home firm is a monopoly. That situation applied to the sales of Volkswagen’s joint venture in Shanghai, which enjoyed a local monopoly on the sales of its vehicles.

318

Shanghai Tie-Up Drives Profits for GM

This article discusses how partnerships in China have helped GM’s profits.

If General Motors believes in God, it must be thanking Him right now for China.

Mainland Chinese sales were by far the brightest spot in GM’s universe last year: sales in China rose 66 per cent while US sales fell by 30 per cent. One in four GM cars is now made in China. Even those cars made in Detroit were partly designed in Shanghai. GM managed to offload distressed assets to Chinese companies: the loss-making, environment-harming Hummer was sold to a previously unknown heavy equipment manufacturer, Sichuan Tengzhong [this sale was, however, blocked by the Chinese government in February 2010], and Beijing Automotive (BAIC) took some Saab technology off GM’s hands. Perhaps most importantly of all, though, China agreed last year to bankroll GM’s expansion in Asia.

In exchange for a deal to sell Chinese minicommercial vehicles in India, GM agreed to give up the 50-50 ownership of its leading mainland joint venture, Shanghai General Motors, ceding 51 percent majority control to its Chinese partner, Shanghai Automotive Industry Corp (SAIC). The Sino-American partnership said this would be only the first of many such deals. Will observers one day look back at that deal and say that was the day GM signed over its future to the Chinese? And does that deal demonstrate how China can save GM—or hint that it might gobble it up? “The quick answer is that Chinese consumers have already saved GM,” says Klaus Paur of TNS auto consultancy in Shanghai, referring to stratospheric Chinese auto sales last year.

Source: “Shanghai Tie-Up Drives Profits for GM,” by Patti Waldmeir, Financial Times, January 21, 2010. From the Financial Times © The Financial Times Limited 2010. All Rights Reserved.

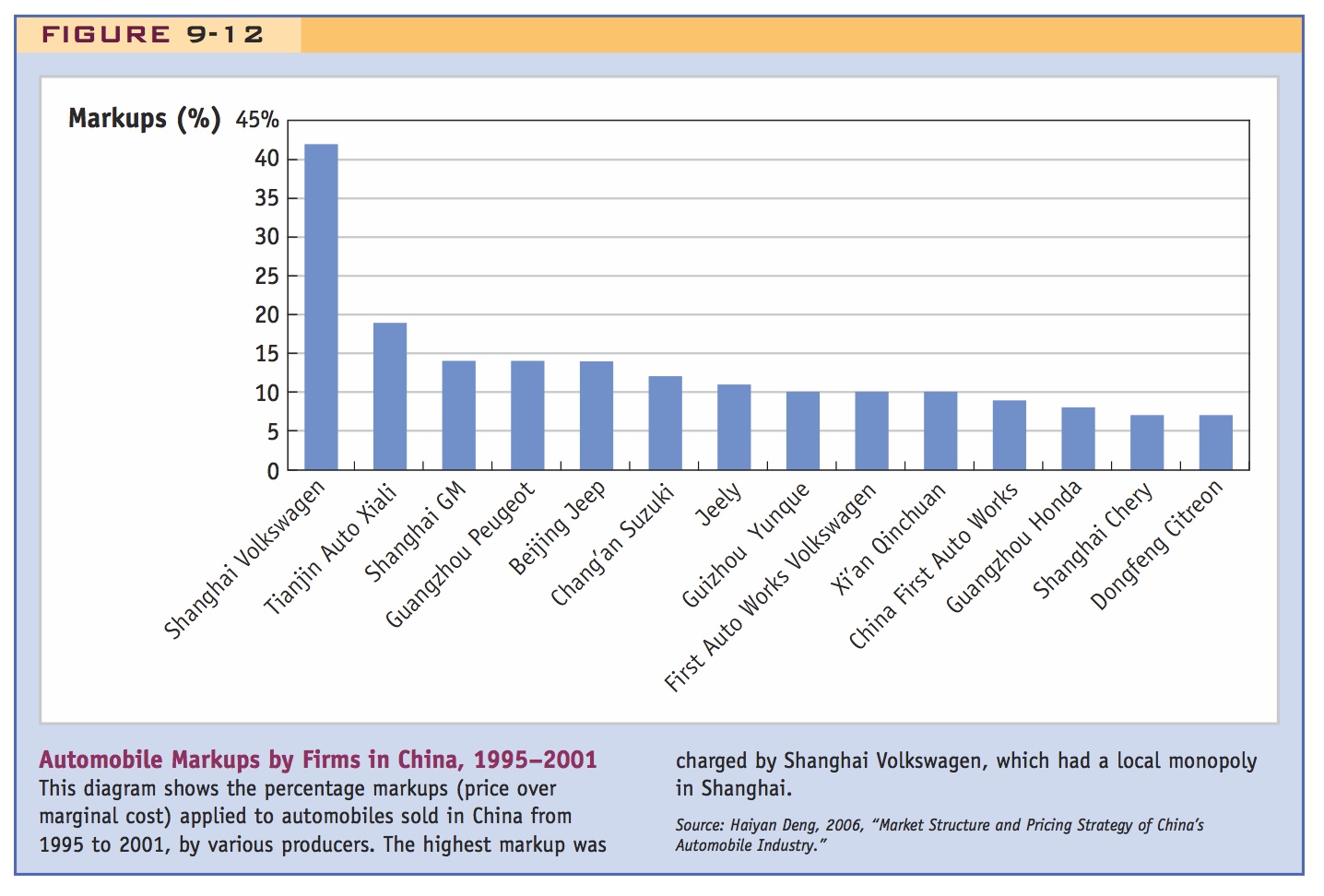

The effect of this local monopoly was to substantially increase prices in the Shanghai market. In Figure 9-12, we show the estimated markups of price over marginal costs for autos sold in China from 1995 to 2001, by various producers. The markups for Shanghai Volkswagen are the highest, reaching a high of 54% in 1998 and then falling to 28% in 2001, for an average of 42% for the period from 1995 to 2001. In comparison, the average markup charged by Tianjin Auto was 19%, and the average markup charged by Shanghai GM was 14%. All the other producers shown in Figure 9-12 have even lower markups.

From this evidence, it is clear that Shanghai Volkswagen was able to substantially raise its prices because of the monopoly power granted by the local government. Furthermore, the Jetta and Audi models produced by Shanghai Volkswagen during the 1990s were outdated models. That plant had the highest production through 2001, despite its high prices and outdated models, so a large number of consumers in the Shanghai area and beyond bore the costs of that local protection. This example illustrates how a Home monopoly can gain from protection at the expense of consumers. The example also illustrates how protection can stifle the incentive for firms to introduce the newest models and production techniques.

Gains to Producers For the tariffs and quotas used in China to be justified as infant industry protection, they should lead to a large enough drop in future costs so that the protection is no longer needed. China has not reached that point entirely, since it still imposes a tariff of 25% on autos, and a 10% tariff on auto parts. These tariff rates are much lower than in the past but still substantially protect the local market. So it is premature to point to the Chinese auto industry as a successful case of infant industry protection. Still, there are some important lessons that can be learned from its experience. First, there is no doubt that past protection contributed to the inflow of foreign firms to the Chinese market. All the foreign auto companies that entered China prior to its WTO accession in 2001 did so under high levels of protection, so that acquiring a local partner was the only way to sell locally: tariffs were too high to allow significant imports to China. As a result, local costs fell as Chinese partners gained from the technology transferred to them by their foreign partners. We can conclude that tariff protection combined with the ownership restrictions for joint ventures has led to a great deal of learning and reduced costs by the Chinese partners.

319

The externality

Second, at least as important as the tariffs themselves is the rapid growth of income in China, which has led to a boom in domestic sales. It is that rapid growth in income that has led China to overtake the United States to become the largest automobile market in the world measured by sales in 2009, and with production exceeding that of Europe in 2013. Tariffs have contributed to the inflow of foreign investment, but it is now the consumers in China who are forcing firms to offer the newest models built with the most efficient techniques. For now, we must leave open the question of whether the high tariffs and quotas in China are responsible for the current success of its auto industry, or whether they just resulted in high prices and lagging model designs that slowed the development of the industry. It will be some years before researchers can look back at the development of this industry and identify the specific causes of its success.

320