Getting Started

Before editing anything, your first step involves setting up an efficient editing environment that takes into account your creative needs, such as what the purpose of your film is and what format you want to deliver it on. By arranging your available technology, resources, and environment correctly, you are improving your chances of creative success later.

The most important point about designing and organizing your editing infrastructure is to work backwards and plan things from the end to the beginning. By that we mean that every decision you make about how you will edit your film and organize your work needs to consider where you want to end up—

You also should make sure your editing space is comfortable and ergonomically set up—

In terms of choosing that hardware to get started, you’ll want to pick a platform that is both robust enough for your particular project and affordable.

NLE Hardware

A nonlinear editing system (NLE system) is simply a computer workstation configured with special software designed specifically for editing moving images. What is revolutionary about the NLE concept is that it allows you to perform editing functions on digitized imagery without irrevocably eradicating original elements or ruining all the work you have already done. In other words, you can experiment creatively with an NLE system, and then you can export that material to physical or virtual media through off-

Therefore, the components of an NLE system involve relatively powerful hardware and specialized software. First, let’s look at hardware considerations:

Computer In theory, you could use any off-

As a student, you may not have access to a professional turnkey system, so you should strategically evaluate what computers are available to you. Laptops are obviously more mobile for editing on or near the set or while you travel. Desktops, on the other hand, can often be upgraded more easily with additional hard drives, video cards, and other hardware, and they easily connect to big monitors to allow you to better view material. We recommend editing on a desktop with a mouse when feasible, but if you are using a laptop, be sure to connect it to a larger monitor and use a mouse if you can. In either case, you always want to edit on a computer with the most memory and computing power available. Particularly if you are working on material at high-

The other computer performance issue to consider is RAM (random-

Monitor For basic editing, many computer monitors, consumer monitors, or televisions can work with most modern editing software programs as a component of larger NLE systems—

Depending on resources, as you select a monitor, do the best you can with the issue of color depth (how many colors the monitor can display—

Cards and Devices A video graphics card is another important issue to consider. The graphics card contains a computer’s graphics processing unit (GPU)—essentially a circuit board inside the computer with its own separate RAM, which controls the data’s output to a monitor, determining how fast and how clear the image can be. Professional editors, of course, use the fastest graphics cards and accelerator hardware available. You may or may not have that inside your available system, or have the ability to upgrade it, but as you figure out how to configure your NLE, keep this issue in mind and find the best solution possible. Beyond all that, remember that because you need to move data in and out of your NLE, the more input and output ports your computer features, the better—

NLE Software

Among the most exciting aspects of the nonlinear editing revolution is the fact that there is a wide range of NLE software systems that are affordable and accessible for consumers and students. Therefore, if you have even the most basic hardware, and you have set it up correctly, there is undoubtedly an NLE software tool available for you.

What factors should you consider before making your choice? Your computer’s operating system is an important one. Some editing software tools only work within the Apple OS, such as Apple’s signature editing product, Final Cut Pro. Others only work in Windows, but many run in both. In addition, many work best with a 64-

Price is another obvious consideration, especially for student filmmakers. Despite the proliferation of more options than ever before, at the professional level, the vast majority of modern films are edited using some version of Avid’s line of nonlinear editing platforms, to the point where it is fair to refer to Avid as the industry standard for professional editing. A smaller number of films use some version of Final Cut Pro (either a legacy version of the original version of the software or the radically revised Final Cut Pro X, rewritten for the OS X operating system in 2011, which is the only version that Apple now supports), particularly independent or low-

As with many software products, some manufacturers periodically offer student pricing on lower-

Additionally, there are even more budget-

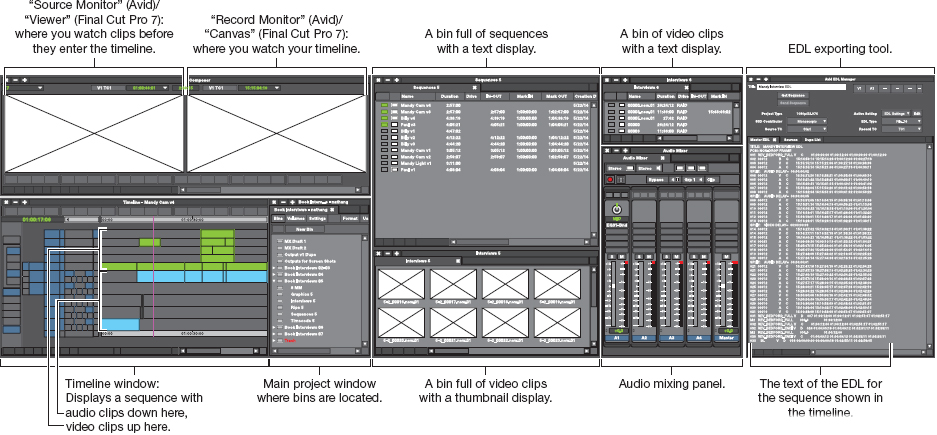

Whatever choice you make, each platform offers a somewhat different user interface, different keystrokes, different looks to the timeline, different options and functionality, and somewhat different nomenclature. Still, there are certain commonalities in how they operate, what to look for, and how to get the most out of them for practical editing work. Among those commonalities are basic features, graphic representations, or icons you are likely to find widely available across multiple systems. They all, for example, have a useful undo function—

Organize a Workflow

Many technical nuances associated with importing, manipulating, and exporting files, and the nature of different formats and codecs, are beyond the scope of this book and the type of filmmaking work you will be doing for the foreseeable future. However, you do need to formulate a workflow—the basic plan for the series of steps you will use throughout the editing process to get files into your NLE system, back up and keep track of them, work on them, save them, and export the final product to your desired finishing media at the end of the process.

The lure of editing is the creative possibilities it offers filmmakers. But as the old saying goes, organization is the key to success. If you are spending much of your precious creative time searching for files, comparing versions, and worrying about lost or misplaced data, then logically you aren’t being creative during those moments. The following phases are the ones you will follow on the path to getting organized and avoiding that eventuality. As noted elsewhere, in the file-based digital workflow era, there are dozens of options and degrees of sophistication to these processes. You need to figure out the simplest, most basic, and safest way to move your files into your system, but no matter what approach you adopt, it will include some version of the following steps:

Logging The process of deciding what material you want downloaded to your NLE system as possible elements to be considered while editing is called logging. Due to limits on storage space, and the need to be organized and not bogged down, it’s rarely a good idea to download every single frame you shot.

Therefore, reference any records or notes you or your crew kept during production about what you shot, from a marked-up script to camera reports or informal notes. If feasible, you might also hook your camera up to a monitor before downloading anything and scan your footage take by take and scene by scene, looking for shots you definitely want to consider and taking note of the timecode, if it is available, to make it easier to find that material. As you scan your way through shots, write a report that lists the scenes, takes, basic descriptions, and timecodes of shots that particularly interest you. With many modern NLEs, you can do this during the download process by viewing footage and simply telling the software which shots you want. Many systems also include dialog boxes for you to manually input various kinds of metadata information about the clip.

FILE APPS

FILE APPS

Research the range of widely available and often inexpensive apps that are designed to help people catalog files on hard drives, listing results in easily searchable PDF documents. FileMaker Pro database software has long been a favorite for this kind of work, and Microsoft’s Excel spreadsheet technology is also widely used. Other popular applications that are simple to use and readily accessible are DiskCatalogMaker, WeTransfer, and MPEG Streamclip.

Ingest Obviously, you will need to transfer captured image and sound files from your recording media to your NLE system’s hard drive, so that you can organize and work on them. How you transfer the images to your computer depends on what format and media you shot them in, what system you are using, and personal preferences. Among the possibilities are film, analog videotape, digital videotape, or—more likely these days—digital image files, either standard definition or high definition.

With modern cameras, you will typically apply settings as you shoot, telling the camera what file format you want the images to be translated into. This way, you will have established files on your recording media that can be seamlessly transferred to a computer via any of several types of digital interface connectors now available, or via a removable drive or solid-state card that plugs into your computer. In fact, there are currently dozens of ways via dozens of input methods to transfer digital files from a camera to your NLE, depending on your camera and how you configured your NLE system, as discussed earlier. You might end up using a standard USB connection, a FireWire connection, a faster Thunderbolt connection, or even HDMI or Ethernet technology for even faster data transfer. On the other hand, if you are still using digital videotape, you might have to connect a video tape recorder (VTR) to your NLE system.

You might also need one of several different kinds of capture cards, which are really circuit boards for your NLE computer that serve as an interface for ingesting different kinds of file formats into your system. Some of these technologies can also transcode a file from one format to another, convert the image up or down from standard definition to high definition, improve the speed of your computer’s ability to do all this, and much more. For now, your goal should be to find the simplest, fastest, most straightforward way of moving captured image files to your computer.

ALWAYS AUTO-SAVE

ALWAYS AUTO-SAVE

Remember to use the auto-save function on your NLE system to create an incremental backup on your hard drive at least every 10–15 minutes. That way, if you are faced with a power outage or nonrecoverable computer crash, you will not lose more than a few minutes of work.

Backup/Storage Another advantage of working in the digital era is the fact that large hard drives are relatively accessible. On any project, among your first steps should be the act of copying all media and source material to a redundant drive or set of drives of one type or another. If at all possible, keep those drives in a different location from where you are working for extra security. Depending on resources and logistics, you may even want to keep a RAID (redundant array of independent disks) system on-site—powerful, automated storage systems that are constantly backing up files while you work. They can range in price from under one hundred dollars to hundreds of thousands of dollars, depending on their size and degree of sophistication.

The other advantage that is available to you at modest cost is the fact that there are a wide range of consumer-based cloud storage services, such as Dropbox, and automated cloud-based archiving services, such as CrashPlan and Carbonite—that permit you to upload full or compressed individual files; copies of your entire NLE project and EDL (see here); or, in some cases, a mirrored image of your entire hard drive in order to achieve security off-site in a relatively affordable manner. Other ideas include simply emailing yourself or a fellow student backup copies of the project at the end of each day.

BACKING IT UP

BACKING IT UP

Figure out at least five different ways you can back up a basic video clip currently in your possession. The clip and its source or format do not matter for this exercise—it could be home video you took with your phone. The idea is to figure out ways to copy it and move it to multiple locations at the best quality possible as a security exercise. Use only the media, online services, cables, or other technology you have, without spending a dime or borrowing technology from others, and make sure the clip has zero chance of being lost for the foreseeable future. Write a couple of paragraphs explaining your choices, which of them would be useful in a basic nonlinear editing environment on a student project if the original source version of the clip were somehow eradicated, and why.

Resolution As you import and organize material, the other thing you need to figure out is what resolution you want to edit your movie in, because resolution impacts the size of files and therefore how much work and memory your computer has to dedicate to rendering and dealing with them. This is where the terms offline editing and online editing enter the discussion. In essence, at this stage, you are deciding whether to edit material in its native resolution and file size—typically higher-quality files you imported into your NLE exactly at the size they were originally recorded and saved in, a process often referred to as using an “online workflow”—or whether to change files to a lower resolution, which more or less means a lower-quality format and a lower-quality look on your monitor, but which makes it easier for your system to work with image data during editing (offline editing). In that scenario, you will need to reassemble the movie using your original higher-resolution elements during the finishing stage, which is often called the “online edit,” or the conforming process. (See Tech Talk, for more on the distinction between offline and online editing generally, and here for a deeper look at a typical offline/online workflow, and also the difference between using an “online workflow” throughout and performing an “online edit” after the offline process. See also Producer Smarts: Stretching Resources, below.)

Stretching Resources

As a student, you need to keep things as affordable and logistically straightforward as possible while serving your project’s needs as best you can. Here are a few important things for you to consider as you make workflow and technology choices:

When building an NLE system, how do you balance your need to moderate cost with your need for the most flexible system available, so that it can help you get as much related work done as possible within the editorial suite? Because you can find cheap or even free basic editing software on the Internet, you need to evaluate whether that is a better move than forking out precious cash to purchase a more sophisticated system whose cost you might be able to amortize over several projects. Evaluate the trade-offs.

When building an NLE system, how do you balance your need to moderate cost with your need for the most flexible system available, so that it can help you get as much related work done as possible within the editorial suite? Because you can find cheap or even free basic editing software on the Internet, you need to evaluate whether that is a better move than forking out precious cash to purchase a more sophisticated system whose cost you might be able to amortize over several projects. Evaluate the trade-offs. Will your project be rendering-heavy? If so, have you accounted for that requirement with your hardware? Putting together an NLE system on your laptop is great, but if processing the images is continually slowing you down, you need to decide if you should find a way to get a more powerful computer, or even more than one computer. What will the cost be of working at a slower pace compared to purchasing or renting more equipment?

Will your project be rendering-heavy? If so, have you accounted for that requirement with your hardware? Putting together an NLE system on your laptop is great, but if processing the images is continually slowing you down, you need to decide if you should find a way to get a more powerful computer, or even more than one computer. What will the cost be of working at a slower pace compared to purchasing or renting more equipment? Is all your equipment compatible? Do you have the right cables for the inputs and outputs on your computer? Have you done enough testing of systems and storage to have confidence that your infrastructure is in good shape for handling the project? Test and plan strategically to avoid spending valuable time dealing with unanticipated work-arounds at the 11th hour.

Is all your equipment compatible? Do you have the right cables for the inputs and outputs on your computer? Have you done enough testing of systems and storage to have confidence that your infrastructure is in good shape for handling the project? Test and plan strategically to avoid spending valuable time dealing with unanticipated work-arounds at the 11th hour. Are there online resources and free technologies you can add to the mix to strengthen your hand? Are there tasks you can get help from classmates on—trading your services for theirs on specific aspects of the work?

Are there online resources and free technologies you can add to the mix to strengthen your hand? Are there tasks you can get help from classmates on—trading your services for theirs on specific aspects of the work? Do you have backup tools, stable power, and proper security? What is your backup plan if you lose power or suffer a hard-drive crash?

Do you have backup tools, stable power, and proper security? What is your backup plan if you lose power or suffer a hard-drive crash? Most important, is your plan viable for how you expect to finish? Will mastering your movie to your chosen form of media be served by your chosen workflow? You need to be confident in knowing that you can finish long before you start.

Most important, is your plan viable for how you expect to finish? Will mastering your movie to your chosen form of media be served by your chosen workflow? You need to be confident in knowing that you can finish long before you start.