Find the Rhythm

As noted, there are important rules, techniques, and styles to consider when editing a movie, and we will discuss them shortly. First, however, you need to think carefully about developing a plan for how you want to pace your movie. Some of this is straightforward common sense—

But what is “pacing” in terms of a movie’s narrative to begin with? The simplest way to think about it is that when you pace a movie, you are varying the length of shots/sequences for strategic purposes—

This sequence from Dirty Harry (1971) demonstrates that movie scenes do not need to play out in real time. The audience only sees the phone ringing in the phone booth, then Clint Eastwood running to pick it up, and then the shot of him answering the phone out of breath. All the in-

ECONOMICAL CAUSE AND EFFECT

ECONOMICAL CAUSE AND EFFECT

Although illustrating cause-and-effect is important, there are times when you should be economical in how you do it. You can, for instance, enter a scene or an event in the middle, when certain events have obviously already occurred. When properly executed, this approach will not impact the audience’s sense of continuity, because what the audience does see will remain perfectly logical, even if joined midway through.

Analyze the Material

Beyond the basics, however, consider the subtle impact of your pacing decisions. Even if you want action, too-quick transitions between scenes can cause your audience to lose interest if they can’t keep up. If you transition too slowly, you can bore them and also lose their interest. Either way, if you consistently meet their expectations, you risk losing their interest because they will have the story figured out before you want them to. If you never meet their expectations, you risk alienating or disappointing them—and so on down the line.

Therefore, you need to decide on your editing philosophy as it relates to your specific story overall. This means poring over the script and watching all dailies, every take. Take notes and write yourself scene-by-scene bullet points for what you hope to achieve with each scene and each transition, and the emotional impact you want your audience to feel from each shot, sequence, or cut. Many editors say this process of immersing yourself in your story and its corresponding elements is the actual hard part of editing, and if you can master a working method of making yourself a road map, the other, more mechanical parts of cutting sequences together will be far less painful.

CUT FOR EMOTIONAL IMPACT

CUT FOR EMOTIONAL IMPACT

As you analyze material, remember that the most important thing is how your cuts will end up impacting the viewer emotionally. Therefore, if you take the time and effort to identify those spots where emotional impact is crucial, it will be easier for you to decide the precise point at which to make the cut, how long to make the shot, and so on.

Where do you want to meet your audience’s expectations? Where do you want to surprise or shock them? Where do you want to leave conclusions open for their interpretation? As many veteran editors advise, look for big issues or concerns: Is a particular scene repetitive, or could it be moved to a different location in the narrative? Is there a character that is superfluous and adds nothing to moving the story forward? These are creative issues to think about before you cut anything. You don’t always need to have hard and fast conclusions to proceed—your feeling about the material may well evolve as you are editing it. But you at least need a beginning point of view, as well as a basic understanding of what you think your audience may be expecting. After all, how can you either meet their expectations or deviate intentionally from them if you have given no thought to what they might be expecting to begin with?

To find the right pace and rhythm for your piece as you study each scene and make your notes, ponder the core issues of cause, effect, motivation, continuity, and logic.2 Every action or event you show in your film needs to have a reason for happening, and a certain logic to it—either real-world logic or logic within the context of the world you are creating in your story. Particularly in a fantasy, sci-fi, or animated film, your edit should set up the rules of that world. For example, the coyote can keep running off the cliff after the roadrunner, unless he looks down. This doesn’t mean, however, that events always need to take place in linear order—that all depends on your creative intent. In crime dramas, for example, it is commonplace for viewers to see the results of the crime at the start of the show—police examining a crime scene or a corpse of someone who has been murdered—even though we won’t get the details of how the crime happened, and who committed it, until much later. But even with that example, there is logic to it: a crime has been committed, and now we will be told the story behind that crime. One of the most classic examples is in Sunset Boulevard (1950), which starts out with the star of the film, William Holden, asking the audience if they want to know how his character wound up dead floating in a swimming pool.

More generally, though, logic should prevail even when your overall story structure is complex. How you get there, exactly, is the magic of editing. You do not necessarily need a detailed scene showing someone drinking to know in a different scene that the person is drunk. But what if someone is doing drugs? If you skip over showing some aspect of that reality, we might see the person inebriated later but have no idea if that is because he or she was doing drugs or was drinking, or if there was some other cause, such as illness. Therefore, you need to illustrate the cause in some fashion to have the effect make sense.

DON’T OVERDO THE MUSIC

DON’T OVERDO THE MUSIC

When making decisions about what kind of music, and how much, to add to your story—and where to add it—keep in mind that music works best in a dramatic narrative when it appears to be naturally occurring or has a specific reason for occurring. Therefore, be judicious in your use of music, and remember that there are many classic films that minimize or do without music entirely, including Fritz Lang’s M (1931) and the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men (2007).

But what do we mean when we say an element has to “have a reason” for being there? Isn’t modern cinema filled with all sorts of eye-candy action sequences and cool visual effects that add little or nothing to the narrative but that set audience tongues wagging?

Well, yes, and that’s precisely the point. As a beginning filmmaker, this should not be your agenda. First, most of those movies are not necessarily ones you will remember with passion. You might remember the scene, or the shot, but will you be moved by the story? And second, by definition, if the audience comments on a shot or an edit, even if they are being complimentary, that means they are thinking about something other than the story—in fact, they are outside the movie-watching experience altogether if they are focused on such matters. You want them thinking about story first, second, and always. In fact, editing-room floors throughout the history of cinema are littered with impressive shots, stunning effects, sophisticated dance numbers, and more—bits and pieces of famous motion pictures that were discarded for the simple reason that they did nothing to advance the narrative and frequently took away from it. The original opening scene of Toy Story (1995) was cut because of this, although the idea did wind up as the opening of Toy Story 2 (1999). Such scenes, no matter how well crafted, come from “outside” the movie and therefore need to be removed. (Editors, both in film and in writing, frequently refer to this necessity as “killing your darlings,” since they are periodically required to remove some of their best work from a movie.)

As discussed in Chapter 10, you will also be deciding where, how, when, and—most important—why you will or will not be adding music and other sound elements to various scenes. On a professional project, you will be working with an entire team of sound professionals to execute those sound decisions; on a student project, you will most likely be doing all that work yourself. In either case, it is during the picture-editing phase that you will make those decisions, and you will be inserting, for the time being, temp music and sounds to illustrate what you are going for in order to provide the necessary impact for you to continue wading your way through the editing process. At this point, it is important to reiterate that music is central to the building of emotion and tension in a motion picture—if you use it judiciously.

Thus, for both picture and sound elements, it makes a lot of sense to be analytical and almost clinically objective in terms of examining your available material and pondering the editing approach that best fits your material before and during the cutting process. By doing so, you will find yourself well on your way to organically figuring out the pace you want for your story.

DRAGNET REDO

DRAGNET REDO

Head to YouTube and examine the opening 2:45 of the following clip from a 1953 episode of the classic television crime drama Dragnet: www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mm0TjfQzf-k. For years, editors and instructors have been using Dragnet as a show that exemplifies the kind of stilted, back-and-forth conversational editing style we have warned you to avoid. Watch this clip and then write your analysis or suggestions for how the editing could have been more interesting in terms of when transitions occurred or could have occurred, what elements could have been easily introduced to make it less stilted, and where you might have changed transitions or other elements to spice things up. There is no one right or wrong answer to this challenge—the idea is for you to understand how and why it is important to make conversations in your work look and sound more sophisticated and interesting than the kind of old-fashioned approach that was popular during the Dragnet era.

Transition In and Out

Before we discuss the types of transitions you can use to tell your story (see here), you first have to think about where and when you want there to be transitions to begin with—that is, where you want to place your edit points. Generally speaking, how does a beginning editor figure out when exactly to make a cut? Where is the “sweet spot” in terms of knowing where to insert a transition? And how do transitions work in the cinematic storytelling process anyway?

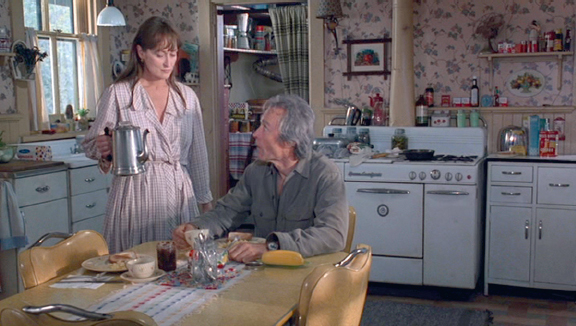

This scene from The Bridges of Madison County (1995) lets the conversation between Clint Eastwood and Meryl Streep play out naturally, without over-mechanical cuts.

There is, of course, no single, all-encompassing answer to these questions, because it all depends on the specifics of the shot, the scene, the sequence, the story, and your overall creative intent. However, there is a general guideline you can keep in mind as you ponder where to place transitions: much of the time, it is a good idea to get into a scene as late as you can, and out of a scene as early as you can.

“You want to be able to tell the story in the most economical way possible,” advises William Goldenberg. “Each scene has a beginning, middle, and end, but you also have to worry about the overall arc of the story. So traditionally, you want to come into the scene at a high point and leave at a high point. If every scene is structured with the same beginning, middle, and end, that doesn’t do much for maintaining a rhythm. But if you always ask yourself, for each scene, what is the latest I can get into the scene, and the earliest I can get out, then each scene will naturally come out [with a somewhat different pace] that works.”

There are exceptions, naturally, where, for emotional impact, you will need to linger on an event. But Goldenberg’s general point is that if you search for your first available opportunity to transition from one scene to the next, the mere insertion of the transition—provided you execute it properly—will create what he calls “a pop for the narrative drive,” which keeps your film’s pacing on track.

When it comes to transitions in conversation within a scene, insert them in places where they will aid and advance the overall pacing of your movie while impacting the viewer emotionally, acting in an organic, realistic way. Avoid monotone, mechanical back-and-forths, with cuts happening between two characters just as each one finishes his or her entire line of dialogue. This is a common occurrence in the work of inexperienced editors, but it isn’t a particularly realistic way to cut, as it makes the scene seem unbelievable and thus boring. Keep in mind that people normally pause, speak over each other, glance about, get distracted, change the tone of their voice, and switch topics when engaging in real conversations.3 (See Action Steps: Cutting a Conversation, below.)

SLOW DOWN

SLOW DOWN

Slow down and relax. There are so many creative and technical issues involved in editing a movie that some students tend to lose themselves in the impulse to tackle editing chores globally; focus on your current task only, and go one step at a time.

ACTION STEPS

Cutting a Conversation

In Chapter 10, we discussed how to edit dialogue. However, the film editor is the one who will combine sound and picture elements into full conversations in order to hold the viewer’s interest and advance the story. Generally, putting a conversation together successfully means you have properly considered anticipation on the part of one or both speakers, their reactions, and whether your creative intent requires you to emphasize one actor over another visually. With all that said, how best can you pace a conversation? Here are some basic considerations:

As discussed, be intimately familiar with your script and how, exactly, the writer and director envisioned the conversation unfolding. Your script may even have directions about reactions and environment to consider.

As discussed, be intimately familiar with your script and how, exactly, the writer and director envisioned the conversation unfolding. Your script may even have directions about reactions and environment to consider. Likewise, be intimately familiar with your available takes. On major features, the various takes the director wants the editor to consider among his options during the dailies process are called circle takes.4 On your first student film, you should consider all takes. Watch and rewatch them, make notes about your favorites, and organize them into folders.

Likewise, be intimately familiar with your available takes. On major features, the various takes the director wants the editor to consider among his options during the dailies process are called circle takes.4 On your first student film, you should consider all takes. Watch and rewatch them, make notes about your favorites, and organize them into folders. Be cognizant of continuity. Often, conversations are filmed over the shoulder, and you are usually going to want to obey the 180-degree rule (see here). Generally, this means you will be cutting between shots of each conversant, unless your creative plan requires wide shots of both people in the same shot. Either way, search for the best performances that obey continuity, rather than putting in shots that are illogical when juxtaposed with other shots in the conversation.

Be cognizant of continuity. Often, conversations are filmed over the shoulder, and you are usually going to want to obey the 180-degree rule (see here). Generally, this means you will be cutting between shots of each conversant, unless your creative plan requires wide shots of both people in the same shot. Either way, search for the best performances that obey continuity, rather than putting in shots that are illogical when juxtaposed with other shots in the conversation. Consider the space, or gaps, between lines from each actor. If you use different takes from each, there could be an awkward or uneven gap of time between when one person stops speaking and the other starts. It’s not that you don’t want gaps—such gaps, hesitations, brief moments of distraction, or waiting are normal in real-world conversations. You just want to make sure the gaps seem natural.

Consider the space, or gaps, between lines from each actor. If you use different takes from each, there could be an awkward or uneven gap of time between when one person stops speaking and the other starts. It’s not that you don’t want gaps—such gaps, hesitations, brief moments of distraction, or waiting are normal in real-world conversations. You just want to make sure the gaps seem natural. Concentrate more on dialogue audio than the corresponding picture. If performances are right and natural, this should be preferred over a take in which dialogue is stilted or weak, no matter which one has the stronger picture associated with it.

Concentrate more on dialogue audio than the corresponding picture. If performances are right and natural, this should be preferred over a take in which dialogue is stilted or weak, no matter which one has the stronger picture associated with it. Along those lines, if dialogue was recorded separately, always search for your best audio performance and include the best picture that does not conflict with it. Remember that if you love the picture from a take in which the actor’s moving lips are not visible, but you aren’t crazy about the audio track from that take, you may have the option to add replacement dialogue later, as you learned in Chapter 10.

Along those lines, if dialogue was recorded separately, always search for your best audio performance and include the best picture that does not conflict with it. Remember that if you love the picture from a take in which the actor’s moving lips are not visible, but you aren’t crazy about the audio track from that take, you may have the option to add replacement dialogue later, as you learned in Chapter 10. Once you have your best audio-performance elements, commit to them and adjust picture elements while finalizing the conversation. You might add inserts (a nervous man tapping the table with his thumb), cutaways (villains coming through the back door), or reactions from a picture point of view.

Once you have your best audio-performance elements, commit to them and adjust picture elements while finalizing the conversation. You might add inserts (a nervous man tapping the table with his thumb), cutaways (villains coming through the back door), or reactions from a picture point of view. You may also end up “rolling” initial picture edits to make the conversation look more seamless. Rolling picture basically means using tools to lengthen a clip on one side of your edit and shorten the clip on the other side. Doing so does not change the length of the overall scene but can change visual focus or emphasis in the shot. Typically, when you roll the edit point forward in a shot, you are doing so to arrive sooner at what the speaker’s reaction will be when he or she finishes talking and starts hearing the other person’s reply. If you roll the picture backward, you are doing so to show anticipation on the part of the speaker just before or as he or she begins speaking—an eye twitch, a frown, a brow furrowing, and so on. Split edits, or L cuts, which we discuss later in this chapter, are useful for this kind of effect.

You may also end up “rolling” initial picture edits to make the conversation look more seamless. Rolling picture basically means using tools to lengthen a clip on one side of your edit and shorten the clip on the other side. Doing so does not change the length of the overall scene but can change visual focus or emphasis in the shot. Typically, when you roll the edit point forward in a shot, you are doing so to arrive sooner at what the speaker’s reaction will be when he or she finishes talking and starts hearing the other person’s reply. If you roll the picture backward, you are doing so to show anticipation on the part of the speaker just before or as he or she begins speaking—an eye twitch, a frown, a brow furrowing, and so on. Split edits, or L cuts, which we discuss later in this chapter, are useful for this kind of effect. Finally, keep in mind that much of the subtlety of editing a conversation depends on your creative desires as the filmmaker and thus will require some experimentation to get right. You might, for instance, realize after a few tries that you need environmental music in the background, that your approach resulted in lip-sync problems, and so on.

Finally, keep in mind that much of the subtlety of editing a conversation depends on your creative desires as the filmmaker and thus will require some experimentation to get right. You might, for instance, realize after a few tries that you need environmental music in the background, that your approach resulted in lip-sync problems, and so on.