Editing Basics

Choosing a specific editing approach or style for your movie really just means you are deciding how you want to tell your story. Do you want to tell a linear story made up of equal parts beginning, middle, and end? Do you want to jump through time, back and forth, with flashbacks and more? Do you want to tell the same story from two different points of view? Do you want to tell a looser story or series of stories that are directly connected to one another by little more than a theme or an idea?

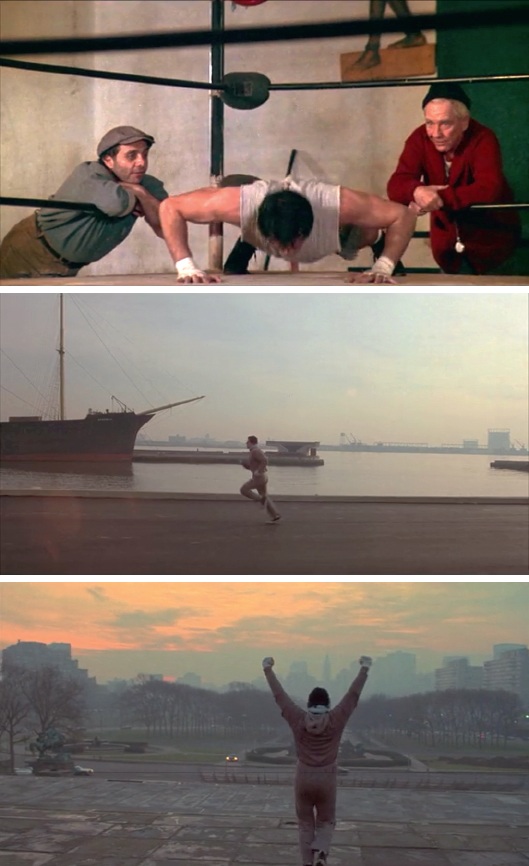

In Rocky (1976), Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky Balboa relentlessly trains for his big fight over the course of many weeks, with the uniqueness of Philadelphia as the backdrop and a motivating piece of music (“Gonna Fly Now” by Bill Conti) driving him along. In this montage sequence, a crucial part of the story was told in a particularly efficient manner that also strengthened the audience’s emotional connection to the story.

These decisions depend on the nature of your story generally, the script specifically, the creative desires of the director (probably you), what picture and sound elements you have available, who your intended audience is, and what type of exhibition plan you have for the movie. No matter the answers to these questions, there is an editing style or methodology that will work for you. Once you pick your approach to the material, you can then figure out the specific types of transitions you wish to make along the way to executing your creative vision.

The Styles

Here’s a basic rundown of the most common approaches. There are others, or hybrids of these and others—and for that matter, you may well discover an entirely new approach along the way. But understanding these basic methods is a big first step toward jumping into the fray for the first time:

Continuity editing. Referring to the most basic and common method of telling a fairly linear story, continuity editing leads the audience through a specific sequence of events that eventually reach a logical conclusion. Often with this approach, the results are what the audience expects, which is why editors sometimes use a continuity approach for certain parts of the movie, and move on to other approaches when they wish to evoke surprise or conclusions the audience may not be expecting.

Continuity editing. Referring to the most basic and common method of telling a fairly linear story, continuity editing leads the audience through a specific sequence of events that eventually reach a logical conclusion. Often with this approach, the results are what the audience expects, which is why editors sometimes use a continuity approach for certain parts of the movie, and move on to other approaches when they wish to evoke surprise or conclusions the audience may not be expecting. Relational editing. Similar to continuity editing, relational editing places a greater emphasis on directly connecting scenes by establishing a specific relationship between them. A simple example of this is the connection of a shot of a baseball pitcher hurling a ball toward home plate to a shot of a batter taking a swing. Viewers will naturally expect that the shot of the ball being pitched will be followed by a shot of the batter swinging, and thus, there is a direct relationship between the two.

Relational editing. Similar to continuity editing, relational editing places a greater emphasis on directly connecting scenes by establishing a specific relationship between them. A simple example of this is the connection of a shot of a baseball pitcher hurling a ball toward home plate to a shot of a batter taking a swing. Viewers will naturally expect that the shot of the ball being pitched will be followed by a shot of the batter swinging, and thus, there is a direct relationship between the two. Montage or thematic editing. With montage editing (thematic editing), editors are connecting images based on a central theme or idea to efficiently convey information or ideas in a concise and powerful manner. Therefore, unlike with many other approaches, there is often no attempt made with thematic editing to have events unfold in a strictly linear manner. The notion is built on a classical montage technique developed in the 1920s that later evolved and grew to influence commercials, music videos, and avant-garde filmmaking. But the montage is now frequently used in narrative filmmaking to compress time or summarize events at a particular point in the story (see Action Steps: Art of the Montage, below), often to relate to an overall theme. To comprehend the power of the montage to aid narrative storytelling, refer to the famous montage in the original Rocky movie (1976), above.

Montage or thematic editing. With montage editing (thematic editing), editors are connecting images based on a central theme or idea to efficiently convey information or ideas in a concise and powerful manner. Therefore, unlike with many other approaches, there is often no attempt made with thematic editing to have events unfold in a strictly linear manner. The notion is built on a classical montage technique developed in the 1920s that later evolved and grew to influence commercials, music videos, and avant-garde filmmaking. But the montage is now frequently used in narrative filmmaking to compress time or summarize events at a particular point in the story (see Action Steps: Art of the Montage, below), often to relate to an overall theme. To comprehend the power of the montage to aid narrative storytelling, refer to the famous montage in the original Rocky movie (1976), above. Parallel editing. Parallel editing is a technique in which editors interweave multiple story lines or portions of story lines. It is an approach frequently used in television, in which multiple characters and plot lines and subplots are commonplace. It is also an approach in which it is typical to vary the pace and rhythm of the overall piece depending on which story or characters are being followed.

Parallel editing. Parallel editing is a technique in which editors interweave multiple story lines or portions of story lines. It is an approach frequently used in television, in which multiple characters and plot lines and subplots are commonplace. It is also an approach in which it is typical to vary the pace and rhythm of the overall piece depending on which story or characters are being followed. Time expansion or contraction (elliptical editing). With this technique, time is frequently drawn out or pulled in for both creative reasons and to allow movies to achieve desired run times. For instance, watching a mobster unload a body from his car, drag it around back, and bury it is something that may well, in the finished product, begin with the mobster unloading the body and then cut to the finish, in which he is shoveling the last bits of dirt on the body in the grave he prepared around back. It is obvious what happened between the two events, and so editors can combine them and thus compress time in that particular sequence. On the other hand, if your story depicts a speaker talking on a stage while an assassin aims his gun and prepares to take his shot, you may want to expand time to build suspense. This method is sometimes called elliptical editing because the omission of pieces of the sequence results in the visual equivalent of grammatical ellipses.

Time expansion or contraction (elliptical editing). With this technique, time is frequently drawn out or pulled in for both creative reasons and to allow movies to achieve desired run times. For instance, watching a mobster unload a body from his car, drag it around back, and bury it is something that may well, in the finished product, begin with the mobster unloading the body and then cut to the finish, in which he is shoveling the last bits of dirt on the body in the grave he prepared around back. It is obvious what happened between the two events, and so editors can combine them and thus compress time in that particular sequence. On the other hand, if your story depicts a speaker talking on a stage while an assassin aims his gun and prepares to take his shot, you may want to expand time to build suspense. This method is sometimes called elliptical editing because the omission of pieces of the sequence results in the visual equivalent of grammatical ellipses. Post-classical editing (MTV style). A more recent technique, post-classical editing is nicknamed MTV style because it became popular through its use on music videos and commercials in recent years. The basic approach involves particularly fast pace, rapid cuts, short shots, and more jump cuts than in classical techniques.

Post-classical editing (MTV style). A more recent technique, post-classical editing is nicknamed MTV style because it became popular through its use on music videos and commercials in recent years. The basic approach involves particularly fast pace, rapid cuts, short shots, and more jump cuts than in classical techniques.

DON’T INSIST ON PERFECTION

DON’T INSIST ON PERFECTION

Don’t insist on perfect continuity. We have emphasized continuity and logic as crucial under many circumstances when editing. However, small differences or imperfections are likely to matter less to your audience than either performances or their emotional connection to your story.

ACTION STEPS

Art of the Montage

Stylewise, the montage often involves the adding or mixing of as many shots as possible; keep in mind, however, that there are different kinds of montages. A parallel montage, for instance, involves cutting between different locations or events happening simultaneously, whereas an accelerated montage uses particularly fast or accelerating cuts to overwhelm viewers for creative reasons. Here are some basic ideas about how to construct a montage that meets your creative needs:

Feel free to experiment. Continuity is not always your goal; your objective may even be to disorient or upset or briefly confuse viewers. Therefore, you may want to consider including opposing or clashing images, different-shaped images, symbols, specialized graphics, or even different colors.

Feel free to experiment. Continuity is not always your goal; your objective may even be to disorient or upset or briefly confuse viewers. Therefore, you may want to consider including opposing or clashing images, different-shaped images, symbols, specialized graphics, or even different colors. Play with color tones, resolution, saturation, or contrast in the color-correction process. Color can be a powerful tool in changing moods for viewers.

Play with color tones, resolution, saturation, or contrast in the color-correction process. Color can be a powerful tool in changing moods for viewers. Mix shots up or juxtapose them, meaning you should try combining images that have different screen depth or composition, or move radically between different types of shots—from close-ups to wide shots, and so forth. Similarly, the juxtaposition of ideas—young and old, big and small, happy and sad—is a part of montage editing that is particularly commonplace in commercial/marketing editing.

Mix shots up or juxtapose them, meaning you should try combining images that have different screen depth or composition, or move radically between different types of shots—from close-ups to wide shots, and so forth. Similarly, the juxtaposition of ideas—young and old, big and small, happy and sad—is a part of montage editing that is particularly commonplace in commercial/marketing editing. Freeze shots or use still images to emphasize particular ideas.

Freeze shots or use still images to emphasize particular ideas. Balance the volume of material you present for creative purposes with a realistic understanding of how much your audience can process. Although the montage is often used to create a disorienting feeling, you still want to try to arrange elements in both space and time to be most meaningful to viewers. Thus, you should experiment with presenting your images in different ways—slower and more simply, faster and more complex—and see which allows viewers to better process your message.

Balance the volume of material you present for creative purposes with a realistic understanding of how much your audience can process. Although the montage is often used to create a disorienting feeling, you still want to try to arrange elements in both space and time to be most meaningful to viewers. Thus, you should experiment with presenting your images in different ways—slower and more simply, faster and more complex—and see which allows viewers to better process your message. Build the mixture of images to your main point. If you show a caveman running in fear, men of different eras throughout history running in fear, and modern people running in fear, you are probably doing so to lead up to some point about why they are all running. Perhaps, for instance, your culminating shot or sequence of shots might show the planet exploding—making the point that the end has arrived, which would be a particularly good reason to run in fear, to be sure.

Build the mixture of images to your main point. If you show a caveman running in fear, men of different eras throughout history running in fear, and modern people running in fear, you are probably doing so to lead up to some point about why they are all running. Perhaps, for instance, your culminating shot or sequence of shots might show the planet exploding—making the point that the end has arrived, which would be a particularly good reason to run in fear, to be sure.

The Rules

As alluded to throughout this chapter, there have traditionally been certain concepts that some people view as firm rules for picture editing—rules they believe need to be adhered to for an edited narrative to look and feel right. Others contend that they are general guidelines that should be respected but that do not always need to be adhered to, depending on creative needs and other factors. Let’s examine and contextualize these basic ideas before discussing when it is appropriate to make exceptions.

Some of these concepts are relatively ubiquitous, with the most common rule being the 180-degree rule, as explained in Chapter 7. There, our emphasis was on how you shoot the elements, remembering to capture the conversational shots according to the rule’s requirements, with the camera staying on one side of the conversation or the other throughout. But the idea will ultimately be applied, or not applied, in editing, because you may have chosen to also capture elements that do, in fact, break the imaginary axis line for any number of reasons. In editing, the concept is most frequently applied when doing continuity editing: if you follow the rule, you will always be choosing elements in a conversation that consistently keep one character frame left and one character frame right.

Of course, many notable filmmakers have violated this rule. When you flip the camera to the other side of the axis, it is called jumping or crossing the line. Thus, in editing, if you then proceed to show the action from the other side of the axis, that is called a reverse cut. For this and virtually all other editing rules, there can be good reasons to ignore them, and we will discuss some of those shortly. For the time being, understand that the 180-degree rule is a good basic guideline when doing straightforward continuity editing—a way to make sure viewers are not disoriented or confused.

Another basic idea that is widely adhered to is the notion of the eyeline match, which, again, is seen most commonly on projects that use continuity editing. The idea with the eyeline match is that you want the audience to see the same thing that the character on the screen is seeing. Thus, it’s a basic cut—a character gazes at something we cannot see, and you seamlessly cut to whatever he or she is looking at.

There are reams of other principles that are important for new editors to understand and consider when cutting a project, whether they intend to always follow them or not. Some of the most basic ideas come from famed film director/editor Edward Dmytryk, who wrote several filmmaking books, including a book on editing in which he laid down seven basic editing rules that most seasoned editors seriously consider to this day. Dmytryk’s rules are as follows:

- Never make a cut without a positive reason.

- When undecided about the exact frame to cut on, cut long rather than short.

- Whenever possible, cut “in movement.”

- The “fresh” is preferable to the “stale.”

- All scenes should begin and end with continuing action.

- Cut for proper values rather than proper “matches.”

- Substance first—then form.5

There is logic to all of these ideas of particular value to the beginning editor. For instance, Dmytryk advises us to cut “in movement,” simply because it is generally easier to hide an edit when the footage is moving, and thus blurred, than when it is static and clear. Similarly, a good way to begin and end with continuing action, he advises, is to simply overlap action cuts by three to four frames.

But of all Dmytryk’s suggestions, the first and last ones may be the most important. Making a flashy or technically challenging or visually compelling cut merely because you can rather than because you need to in order to tell your story is just about the worst reason in the world to make such an edit. Likewise, as noted, you will typically need to meld or mix styles or methodologies on most projects rather than adhere rigidly to a single style throughout every scene. Therefore, if you ask yourself with each cut if what you are doing is helpful to telling your story in a way that connects emotionally with your audience, then you are well on your way to making a good editing decision.

In his writings and lectures, Walter Murch has offered up some baseline concepts for film editing that, like Dmytryk’s, are widely respected and adhered to around the industry. Murch proposes the following six basic criteria for deciding where to cut, widely referred to as Murch’s Rule of Six:6

- Emotion—How will the cut impact the audience emotionally at the moment it happens?

- Story—Does the cut move the story forward in a meaningful way?

- Rhythm—Is the cut at a point that makes rhythmic sense?

- Eye Trace—How does the cut impact the audience’s focus in the scene?

- Two-Dimensional Place of Screen—Is the axis being followed properly? (This relates to the 180-degree rule.)

- Dimensional Space—Is the cut true to established physical and spatial relationships?

Murch went on to assign in what he calls a “slightly tongue-in-cheek” manner specific mathematical percentages to these ideas to indicate how much value each should be given in the course of a narrative film. He elaborates today that the assignment of specific values such as 51 percent to emotion, 23 percent to story, and 10 percent to rhythm was “not an ironclad regimen” in that “it is impossible to really quantify any of this exactly, and also it is rare that we can achieve all six at the same time.”

However, Murch adds that such value assignments do have meaning as “a kind of abstract goal” in the sense that if an editor needs to sacrifice or minimize something, he or she should logically minimize from the bottom of the list rather than from the top. “Let go of 3D continuity before 2D, and 2D before eye trace, and so on,” he suggests. In other words, especially at this stage of your career, focus on the ideas behind Murch’s criteria. Understand clearly what he is suggesting is of primary importance—emotion, story, and rhythm—and do the best you can with everything else. If you manage that kind of balance, chances are you are on the right track in terms of editing your narrative in a compelling and impactful manner.7

TRY EVERYTHING

TRY EVERYTHING

Within reason, try everything. By that, we mean use every available take, angle, and element at your disposal within your timeline and resources, and experiment with each of them in the early rough cut to discover your best options.

Breaking the Rules

All of the principles discussed here are solid, nuts-and-bolts concepts that good editors routinely know, consider, and frequently follow when cutting movies. The problem, of course, is that a rigid adherence to them in all situations can result in mechanical cutting that does not always fit the emotional intent of your scenes. Since editing is a highly creative and instinctual endeavor, you need to develop a framework for comprehending when to rigidly adhere to a rule and when to ignore it entirely.

The basic principle, of course, is to make sure you have good reason for violating a rule, such as the 180-degree axis or the eyeline match. Related to that, verify that the reason is a positive one—that your decision in either direction is being guided by an understanding of what your desired audience will, or will not, get from what you are doing. Indeed, many editors suggest that your deciding factor on whether to cross the 180-degree line or break another rule is whether or not the audience will be able to follow what is going on if you do it. So you need to ask yourself if you are confusing the audience or making it easier for them to follow a point you are trying to make or an emotion you are trying to convey. In that sense, it is about common sense. Therefore, as the editor, feel free to experiment with breaking a rule and the consequences of doing so. Once you have tried it, does the scene work? Can the viewer follow along? Is the emotional connection still there or even stronger than before? If so, it was probably a good move. If not, you probably made a mistake and should switch back to adhering to the rule.

DO IT THREE WAYS

DO IT THREE WAYS

Propose three scenarios for how you could edit the following basic scenes, using a different order or style or approach that would subtly change the meaning or impact of the scene: (1) a close shot of a breathless man running, eyes wide in horror; (2) a house exploding and bursting into flames; (3) a car driving slowly along, with the driver’s window slightly down and someone watching.

As you go through this process, be aware that certain ideas can evolve out of basic editing rules that may ironically provide your basic defense for violating those very rules. For instance, a big point is made out of emphasizing performance over style. That, however, may cause you, as an editor, to linger on a shot or sequence longer than you otherwise would. Similarly, poorly executed or ugly shots may cause you to move on more quickly than you would otherwise do, or to resize or reposition the shot. Also, there is an understandable urge to take advantage of master shots as you set the scene for certain sequences—you might want to linger on a particularly beautiful master shot if you think it will help you hold the audience’s interest.

More generally, you may want to violate a particular rule if the intent of the rule is not what you are trying to achieve creatively. The 180-degree rule, for instance, is all about not disorienting the viewer. In Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), the legendary director strategically wanted to disorient the audience during the famous bathroom scene, and so he violated the 180-degree rule to accomplish that goal. In other words, the best reason to break an important rule in the editing process is the same reason for following the rules—to evoke a desired emotional response from the audience.

In this scene from The Shining (1980), director Stanley Kubrick and editor Ray Lovejoy deliberately break the 180-degree rule to disrupt the audience’s expectations.