Structure

Because a film is a highly concentrated experience—a distillation of a story’s key moments—storytelling structure plays a crucial role. Structure, when used to describe a story, means the order in which the story is told, or the way the scenes are set next to each other to form a coherent whole. Structure is important for all films—especially short student films, in which following a formal storytelling structure often means the difference between an emotional and riveting experience and one that is boring and easily dismissed.

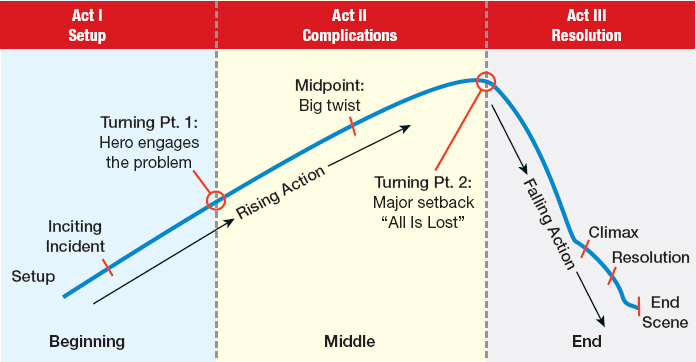

The most frequently used structure in filmmaking is the three-act structure. The three-act structure is not a rule, and of course many dramatists have not followed it. Ancient Greek dramas have only one act. Shakespeare wrote his plays with five acts. But all successful stories, whether they are formally broken up into three acts or not, have the basic attributes of the three-act structure, which roughly translates into beginning, middle, and end. This is a fundamental necessity for class film projects, too.

HOW TO START A LOG LINE

HOW TO START A LOG LINE

It’s especially effective to begin a log line with “When,” “After,” or “During.” These words lend a feeling of action.

The beginning, or setup, of your movie should introduce the main character, or protagonist, and the challenge or crisis he or she will face in order to achieve some specified goal or objective. Often the challenge is personified in another character, called the antagonist.

In the middle, the main character needs to engage in one or more actions that confront the antagonist and move in the direction of the goal. In a well-structured story, each action is more important and has higher stakes than the one before, but the main character doesn’t achieve the goal yet; in fact, at the end of the middle, or second act, it often looks as if the antagonist will prevail.

In the third act, the main character must confront the greatest challenge; vanquish the antagonist once and for all (unless you are planning a sequel); and, in so doing, achieve the goal that was described in act one. Often the resolution in act three occurs because the protagonist realizes that he or she no longer wants what seemed so important in the first act; this movement in a character’s desires or values is sometimes called the character arc. An example might be a story in which the protagonist wants fame and fortune in the first act, only to discover, in the third act, that love is what matters.

THIRD-ACT PROBLEMS ARE FIRST-ACT PROBLEMS

THIRD-ACT PROBLEMS ARE FIRST-ACT PROBLEMS

If you have trouble figuring out the third act, it’s probably because the first act isn’t right yet. Go back to the first act and make sure you have spent enough time giving detail to characters and establishing the primary conflicts.

The third act carries a special burden: it is the key ingredient to a commercially successful film. Marketing research has shown that the last act of a movie is what audiences remember most, and if those final minutes fulfill the audience’s expectations, they will have an overall positive impression of the movie. Of course, this doesn’t mean that the film must finish with a happy ending, and that all issues must be resolved and “tied up with a bow,” because life isn’t like that; creatively and commercially successful films, however, conclude at a place of satisfying resolution and closure. This is often referred to as “what happens in the last reel”—a reference to the fact that movies literally used to be transported on separate film reels. Legendary film executive Louis B. Mayer, one of the founders of MGM studio, reportedly said, “There are only two things that are important in a movie—the first reel and the last reel. And the first reel doesn’t matter so much.”

The three-act structure closely follows the form of the hero’s journey described by mythologist and storyteller Joseph Campbell in his classic book The Hero with a Thousand Faces. In the hero’s journey, he is often reluctantly called to take action to protect a kingdom or the entire world in the first act. When the hero begins his adventure, which is the beginning of the second act, he is involved in a series of battles, quests, or self-discoveries. At his lowest point, the hero suffers a crushing defeat and is killed either in fact or metaphorically, but his spirit rallies and he is resurrected (in the third act); he engages in a final battle with the antagonist and returns home with the world or the kingdom restored or rectified.

A typical feature-film screenplay is 120 pages long. The first act is in the first 30 pages, the second act is pages 31–90, and the third act is the last 30 pages. As you can see, the second act is the longest, and successful screenwriters often break the second act down into smaller sections to keep it manageable and exciting.

Three-act structure

WRITING LOG LINES

WRITING LOG LINES

Log lines are notoriously difficult to write and perfect. The key is not to tell the movie’s story. Instead, you need to do the following:

Engage the listener

Engage the listener Introduce the main character or characters and where the story takes place (also when the story takes place if not present day)

Introduce the main character or characters and where the story takes place (also when the story takes place if not present day) Tell what the big problem is going to be

Tell what the big problem is going to be Make it interesting—leave the listener curious about what happens next (Question: “And then what?” Answer: “You’ve gotta see the movie to find out!”)

Make it interesting—leave the listener curious about what happens next (Question: “And then what?” Answer: “You’ve gotta see the movie to find out!”)

Try writing log lines for three movies you’ve seen, plus for three original ideas.

A five-minute student film might have a five-page script; the middle two to three pages will be the second act, and the first and last pages will be the first and third acts, respectively. In this compressed format, there is less time to flesh out complexities of theme, character, and plot. You will need to find efficient visual mechanisms to convey key information to the audience, and you should try to keep the plot simple and direct. In storytelling terms, short films most closely resemble the literary form of the short story, which announce their theme, quickly set up character and situation, and often rely on a plot twist or significant character transformation in the last paragraphs.

Although the three-act structure is a useful tool, and certainly a concept all screenwriters should be familiar with, it is by no means a strict requirement of good writing. For every writer who follows the three-act structure, there is another who passionately protests its programmatic efficiency, its substitution of creativity with formula, and its tendency for making movies predictable. Like most tools, it is best to think of the three-act structure as a valuable guide or starting point that can also be discarded when the demands of character and storytelling take over. In fact, in the best stories, the structure seems to take care of itself. (See Action Steps: How to Avoid Writing a Bad Student Film, below.)

ACTION STEPS

How to Avoid Writing a Bad Student Film

Some people say, “There are three kinds of student films: long, too long, and way too long.” That’s your first tip: be concise. The most successful student films embrace their brevity and do not overstay their welcome.

Here are six more tips you can use as you are crafting your screenplay to avoid making a bad student film:

Don’t tell a conventional love story, especially if it’s about your recent breakup. We’ve seen it before. If you’re going to make a love story, make it different!

Don’t tell a conventional love story, especially if it’s about your recent breakup. We’ve seen it before. If you’re going to make a love story, make it different! Don’t try to string together disconnected incidents or to tell a “slice of life” story—because those aren’t stories. A story has scenes that build on each other and move forward as the characters seek to achieve their goals.

Don’t try to string together disconnected incidents or to tell a “slice of life” story—because those aren’t stories. A story has scenes that build on each other and move forward as the characters seek to achieve their goals. Don’t strive for natural-sounding dialogue. Great movie dialogue is made up of heightened and concentrated speech. Quentin Tarantino’s films are a good example.

Don’t strive for natural-sounding dialogue. Great movie dialogue is made up of heightened and concentrated speech. Quentin Tarantino’s films are a good example. Start each scene as late as possible, and get out of it as soon as possible. Begin in the middle of the action, eliminate the fluff, and end with the audience wanting to know what happens in the next scene.

Start each scene as late as possible, and get out of it as soon as possible. Begin in the middle of the action, eliminate the fluff, and end with the audience wanting to know what happens in the next scene. Lose the music montages and dream sequences. You won’t have time for an effective montage in a short film, and dream sequences are overused. Concentrate on what the characters want, and show it in dialogue and action.

Lose the music montages and dream sequences. You won’t have time for an effective montage in a short film, and dream sequences are overused. Concentrate on what the characters want, and show it in dialogue and action. Don’t choose a story about making a movie, trying to make a movie, or otherwise trying to express yourself as an artist. You are expressing yourself as an artist by making your movie—now go tell a great story.

Don’t choose a story about making a movie, trying to make a movie, or otherwise trying to express yourself as an artist. You are expressing yourself as an artist by making your movie—now go tell a great story.