Your Screen Is Your Canvas

As a filmmaker, the screen is your canvas, whether you’re making a movie for a tablet, a television, or a big cinema screen. You are responsible for understanding how the canvas can be used. At times, you will be required to use it in a certain way—

Aspect Ratios and Formats

Just as a painter needs to decide what size and shape a painting should be, the filmmaker must determine what the film should look like. The first consideration is the film’s aspect ratio. The word aspect means “appearance,” and a ratio compares two things. The aspect ratio is the relationship between width and height of the screen image. But unlike a painter, who can stretch a canvas to any size and even decide if it will be higher than it is wide, the filmmaker has few choices. Movies come in standard sizes, which have evolved and changed over the last one hundred years. These standards are often called formats because they have clearly defined size and shape characteristics. (Later in this chapter, you’ll encounter the word format used in terms of cameras; the important thing to remember is that a format is just a way of saying that something is standardized.)

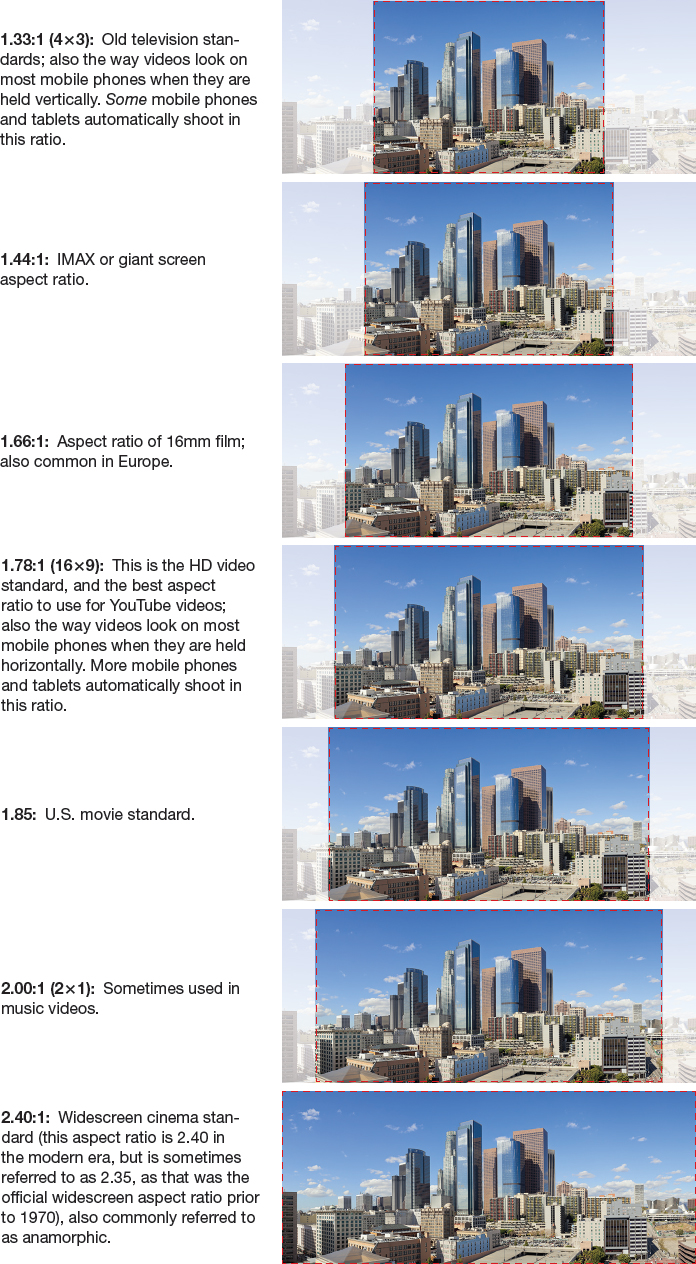

Figure 6.1 shows how the same image looks different in different aspect ratios. You’ll see that with a smaller aspect ratio, the image looks more square, and as the aspect ratio widens, you can see more information on the sides.

Your choice of aspect ratio will be driven by both creative and commercial considerations—what will look best artistically, and where your film is going to be distributed (see Action Steps: Shooting for Multiple Formats, below). For example, if your film is destined to play in cinemas, you can shoot in 1.85 or 2.40 aspect ratios. But if you’re planning to show your movie on a YouTube channel, you’ll want to shoot it in YouTube format (1.78). Wes Anderson’s 2014 film, The Grand Budapest Hotel, uses three different aspect ratios to indicate different time periods, and it is a perfect way to explore the ways aspect ratios change how much of a scene you can see.

FIGURE 6.1The same image in different aspect ratios

Chris Pritchard/Getty Images.

PROTECT FOR MULTIPLE FORMATS

PROTECT FOR MULTIPLE FORMATS

If your film is going to be shown on any kind of large public screen, it must be formatted to at least 1.78 (1.85 is typically the standard for a studio film). However, it will also need to be watchable on mobile devices with a 4 × 3 screen. Solution: Protect the 4 × 3 frame, so that nothing important happens at the extreme edges. When shooting, mark your viewfinder with tape to see where the 4 × 3 area will be. You may have to make small compromises on how you frame the shot to accomplish this.

Although some cameras have settings that give you a choice between wide screen and standard formats, what the camera manufacturer means by these words isn’t always the same as what’s standard in filmmaking. You need to shoot something in each format and look for yourself, or check the manufacturer’s specifications manual. On mobile-phone cameras, “widescreen” simply means 16 × 9. (Aspect ratios are often described as “this number by that number.” It is simply another way of explaining the ratio. In this example, 16 × 9 is another way of saying 1.78 [because 16 ÷ 9 = 1.78].) In movies, the ones you see in the cinema, widescreen is anything wider than 1.85—that is, wider than a cell-phone screen—and conveys a sense of epic scope.

Widescreen is often used for stories that have large-scale scenery or settings: movies that take place in nature or in eye-popping, invented worlds, or movies that depict the extreme loneliness of characters dwarfed against a landscape. Widescreen can also make more intimate movies feel less claustrophobic; if a movie takes place entirely in confined spaces, a widescreen approach can give the film a sense of scale, making a “small movie” seem large. Widescreen can seem grandiose, whereas a narrower format, such as 1.33, can direct the audience’s attention more toward the characters and their relationships with one another than on their relationship to the film’s physical setting.

ACTION STEPS

Shooting for Multiple Formats

Sometimes you may need to either capture your images so that they can be displayed in different formats or manipulate the imagery after you’ve shot it so that it works on different-size screens.

Shooting multiple versions. You may need to shoot multiple versions of a scene (also known as coverage), as when you are creating content for an interactive game that might be played on a TV screen (16 × 9) or on a mobile device (4 × 3), or when you must sanitize explicit or offensive imagery or dialogue so that it can be shown to a general audience. This will also give you more choices in the editing room. You need to know what your final format is going to be, and be prepared in case your movie will need to finish in more than one format.

Shooting multiple versions. You may need to shoot multiple versions of a scene (also known as coverage), as when you are creating content for an interactive game that might be played on a TV screen (16 × 9) or on a mobile device (4 × 3), or when you must sanitize explicit or offensive imagery or dialogue so that it can be shown to a general audience. This will also give you more choices in the editing room. You need to know what your final format is going to be, and be prepared in case your movie will need to finish in more than one format. How to fix things if you only have one version. If a film is shot in one aspect ratio but will be shown on others, there are four ways to fix the problem.

How to fix things if you only have one version. If a film is shot in one aspect ratio but will be shown on others, there are four ways to fix the problem.- Letterboxing puts a black bar above and below the frame to preserve the original aspect ratio. For example, if a movie is going to be shown on an IMAX screen and you want to preserve a 1.85 aspect ratio, you would place black horizontal space above and below the image on IMAX’s 1.44 screen. This is commonly done when showing a 16 × 9 film on a 4 × 3 screen.

- Pillarboxing puts black bars on the right and left of an image. You’d use this if you wanted to show a 4 × 3 film on a 16 × 9 screen.

- Windowboxing, a combination of letterboxing and pillarboxing, completely wraps the film in a black frame so that its entire aspect ratio will be preserved.

- Another fix is panning and scanning—a process in which the film is altered for the screen by recomposing shots to make sure the audience can see what is happening. For example, if a film was shot in 2.40, and important information happened at the edge of the frame, the film would be panned and scanned for each scene, shot by shot, before it could be shown on television.

While panning and scanning may seem to be a practical fix, it is expensive and time-consuming, and it is disdained by many filmmakers as it alters the original composition, depriving the audience of seeing the work as the filmmaker carefully composed it. Some filmmakers demand that their movies be shown in their original aspect ratio on all devices, which means that their films need to be letterboxed. However, letterboxing makes the image quite small on mobile devices, so movies formatted this way may be less appealing to consumers.

Special Formats: 3D Stereoscopic and Giant Screen

We’ve explored the conventional size and shape of most films, but there are two important formats that fall outside the norm: 3D stereoscopic and giant screen. These formats have gained increasing popularity in recent years, and there are more than 50,000 3D stereoscopic–

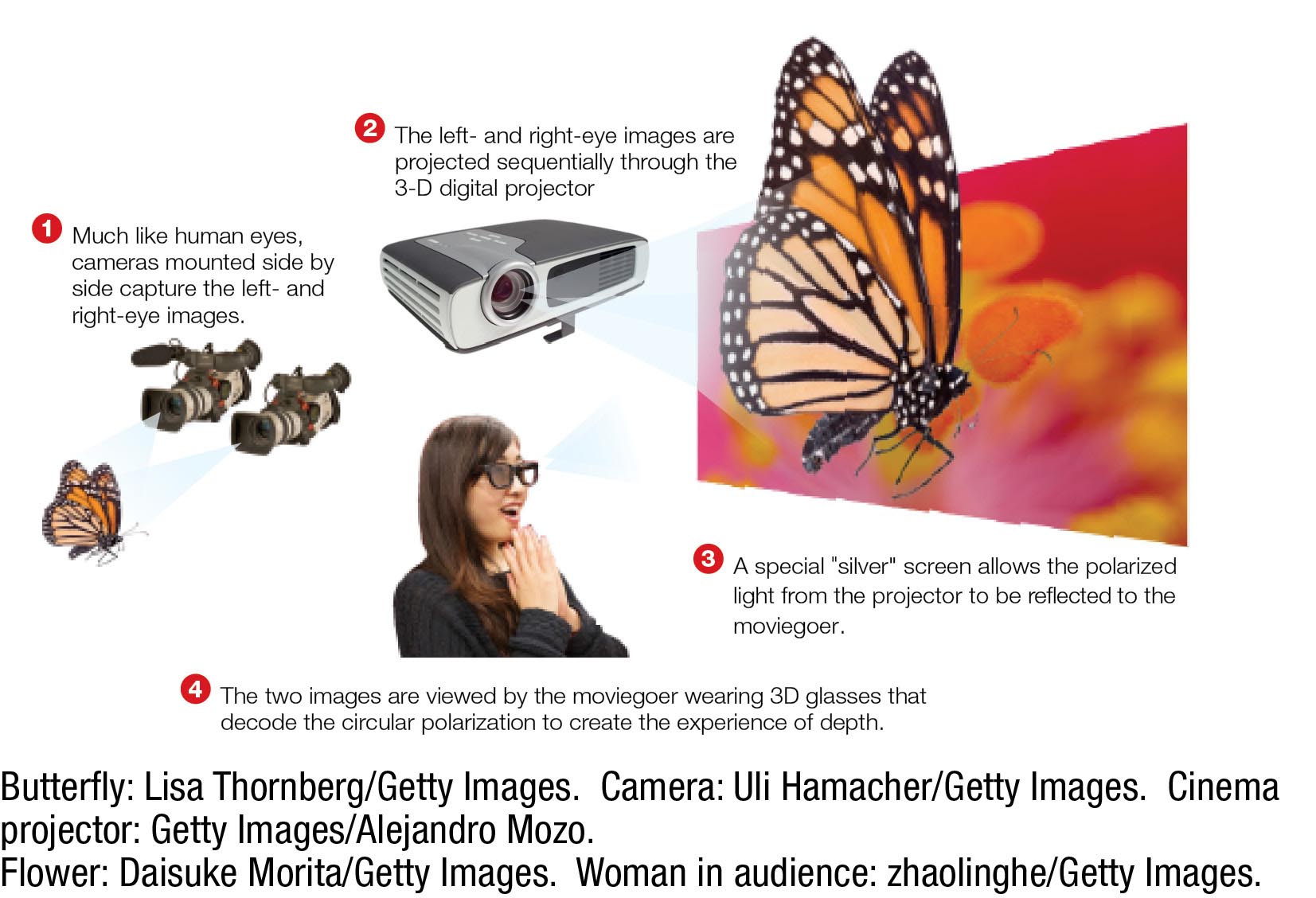

3D stereography is a process that creates a visual illusion of dimensionality by showing two different images, one for the right eye and one for the left eye, mimicking the way our eyes perceive depth with stereoscopic vision. There are numerous methods for achieving this—

3D stereography

If your film will be shown in 3D, your creative challenge is to use the added depth in your canvas, sometimes referred to as z-

Giant screen is an inclusive term that applies to IMAX and other large-

WORKING WITH ASPECT RATIOS

WORKING WITH ASPECT RATIOS

Go back to the storyboards or shot sketches you created for Chapter 4. Overlay a frame of 1.85 and 2.39 aspect ratios on the sketches. Is important information missing when you change aspect ratios? Redraw a key shot so that the important visual information will be seen no matter which aspect ratio might be used. This will inevitably result in some creative compromise.

Creative Discussion about the Look of the Film

One of the producer’s most important jobs is to help the director clarify the look of the film and to work with the director and the cinematographer to make sure it can be achieved. We’ll spend a lot of time talking about film looks or styles in subsequent chapters; one area of a film’s look that directly relates to the camera is the resolution of the images.

Resolution refers to how highly detailed each frame is—

Other important image qualities, all of which can also be controlled, are color rendition (the ability to show color), tonal value (the ability to show shades of gray), and contrast (the sharpness of the difference between black and white). Each of these image qualities can convey a storytelling or emotional value; for example, a lot of color may suggest an experience that is more vivid than everyday life: a musical, for example. A lot of contrast may suggest suspense and foreboding, as is common in horror or suspense films. Good producers talk about these creative issues at the beginning of the preparation stage, so that everyone can get on the same page and assemble the right equipment to create the right look and design sets, props, and costumes to support that look. Many studios or producers employ quality checkers, to ensure that all that hard work is being properly projected at your local theater.