Film

Although you may not have the opportunity to use a film camera in this class, you’ll be a better filmmaker if you know how film works, because it is the basis for the aesthetic and technical standards that have shaped the moviemaking experience.

Film is actually a film—

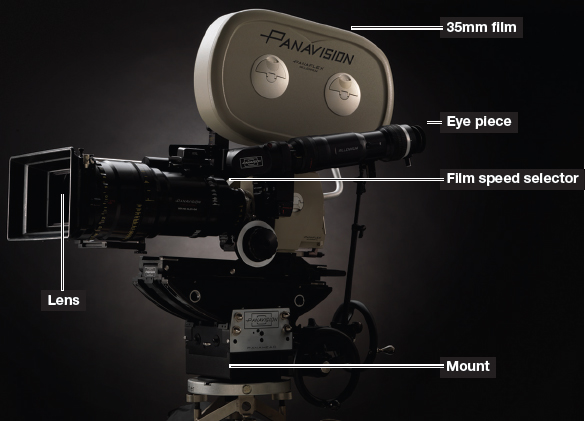

Panavision film camera

Courtesy of Panavision International, L.P.

BUYING FILM

BUYING FILM

When purchasing film for a project, make sure that you purchase all of your film in advance from the same manufacturing run or batch. There can be subtle variances within the same film stock from different batches.

Film Formats and Film Stock

Film comes in two customary formats—35mm and 16mm, which refer to the width in millimeters of the filmstrip. Smaller formats—8mm and Super 8mm—were commonly used as consumer recording media until the widespread adoption of video cameras. Although 8mm formats are not used by general consumers anymore, they have found a home with professionals looking for a more homemade feel or period quality imagery, and with some consumers for recording personal events, such as weddings. In addition, music video directors and some film directors occasionally use 8mm for special sequences. Film also comes in 65mm, which is used for higher resolution on giant screens, or when added details are needed to create better visual effects shots.

FILM MATH

FILM MATH

Film Math for One Standard 1,000-Foot Reel: Based on a camera running at 24 frames per second with 16 frames in every foot of film: 1,000 feet × 16 frames per foot ÷ 24 frames per second ÷ 60 seconds per minute = 11.1 minutes running time before you will need to change magazines. Note that when working with a digital camera, you will not be limited to such short run times generally—one of the advantages of digital touted by many aficionados. On the other hand, that reality only works if you have sufficient recording media storage space to keep going. You will likewise have to stop at some point and change recording cards or hard drives periodically. How much recording media you will need, and how long you can record at one time before swapping media can vary greatly based on several technical factors that are beyond the scope of this book. Just as you would make sure to purchase enough film stock to cover your entire project, make sure you have enough recording media to shoot each day, and a detailed workflow plan for backing up and downloading that material so you can use that media again the next day.

Film is simpler than digital video, even though its ability to create imagery is as complex and in some cases superior. Film technology is well understood, and DPs have over a century of working knowledge on which to draw. Film imagery comes about through two phases: (1) recording, during which the image is captured in the camera, and (2) processing, during which the shot film is taken to a laboratory where chemical processes are applied to the physical film so that the image can be seen and used. Because both of these phases can be individually controlled, film is a fully handcrafted medium and allows its users almost infinite flexibility in capturing and rendering imagery. (See Action Steps: Using a Film Camera, below.)

Unexposed film can be purchased from a film supplier and is called raw stock or film stock. There are different kinds of film stock, which respond to light in different ways. Some film stock produces more vibrant greens or more vibrant reds, some stock has more or less contrast, and other stock is specially adapted to low-light photography. A film stock’s sensitivity to light is called film speed, and it is indicated by ISO, ASA, or EI numbers, ranging from low to high. (ISO refers to the International Organization for Standardization, ASA refers to the American Standards Association, and EI stands for exposure index. The numbers are numerically the same and can be used interchangeably.) Higher ISO films are more sensitive to light, which means they can capture images with less available light; this film stock is called fast. Lower ISO film requires more light to capture an image, and it is called slow.

In professional filmmaking, ISO numbers will generally range from 50 (slow) to 500 (fast). In a bright-light situation, cinematographers will typically use a slower film; in a low-light or nighttime situation, they will use a faster film. For decades, Kodak and Fuji were the two principal producers of raw film stock for motion picture production. In 2013, due to the industry’s digital transition, Fuji opted to discontinue making motion picture film, leaving Kodak as the sole provider of high-end stock for making movies. Today, new stocks continue to be developed by Kodak that allow far better resolution in low-light conditions while still keeping a fine grain. Additionally, since most studio films are scanned (converted into high-resolution digital files) during the editing and visual effects steps, newer film stocks provide better visual information for the scanning process.

The size of the film stock determines the size and technical requirements of film cameras, meaning that cameras are categorized by the size of the film in use—35mm, 16mm, or 70mm (giant screen or IMAX). Unlike digital cameras, for which there are distinctions among consumer, prosumer, and professional models, all film cameras are capable of delivering professional-quality images. However, only professional film cameras have the ability to change lenses, and until recently, they had far more lens choices than digital cameras. Interestingly, among the lingering legacies of film cameras are these kinds of lens choices. Many modern digital cameras are now being engineered so that they can be outfitted with traditional film-camera lensing systems that filmmakers have valued for generations.

Some film cameras, such as the Panaflex, are getting smaller and lighter to operate. Still, many digital cameras are smaller because film itself is a fixed physical size, and there is a size below which film cameras cannot be built. In fact, many professional film cameras are quite heavy. The Millennium camera body alone weighs 17.2 pounds. Add to that a 1,000 foot magazine (the box that holds the film reels on the camera), where the raw stock is held (12 lb.); an extension eyepiece (4.7 lb.); a matte box (5 lb.); a focus-assist unit (2 lb.); a follow focus and rods (3 lb.); a big prime lens (5 lb. or so); and the film itself (4 lb. or so), and you’re up to 50 pounds!

SLOW MOTION

SLOW MOTION

Slow motion is created by shooting more frames per second, or running the film through the camera faster (also known as “over-cranking”). When the images are projected at normal speed, the action appears to move more slowly than normal.

How Film and Film Cameras Work

Film cameras load their film in reels. A standard reel of 35mm film is 1,000 feet long and will run for 11 minutes. The reel was established as a standard length to provide simplicity in film equipment and shipping of actual film. After one reel is used, the camera must be stopped and a new reel loaded. At this point, you (or the first camera assistant) always check the gate—the small rectangular opening through which the film passes when it is exposed to light. Sometimes small pieces of celluloid can break off in the mechanical movement of the film, creating streaks or hairs on the negative. If the gate is clean, the production can move on; if the gate is not clean, it is cleaned with orangewood sticks or compressed air and then the scene is reshot. The fact that film cameras must be reloaded and checked regularly may seem like a disadvantage—and sometimes it is, especially for directors who like to leave digital cameras rolling for up to an hour at a time. On the other hand, many cinematographers and directors feel they get better acting performances because of the urgency film creates; there is a creative energy on the set when film begins to roll, a creative energy made stronger by the realization that each take, each shot, is precious and finite.

Film cannot be seen until it is developed; thus, it is impossible to see what you have shot until the film comes out of the lab. (See Tech Talk: Go Negative!) If there is a problem with the footage, usually a lab technician will call the DP. The production team will then inspect the film to see if the scene needs to be reshot or digitally repaired through a film restoration or visual effects process.

As you learned in Chapter 3, footage that comes out of the lab is referred to as dailies. Traditionally, dailies are telecined (transferring and converting film images for video viewing), so people can watch them without a film projector. Since film cameras do not record sound (unlike cell-phone and consumer digital cameras), film sound must then be synchronized to the picture (see Chapter 11 for more on this discussion). To enable synchronization, a crew member slates each take by physically clapping a stick to the top of a board (known as the slate) to create a sound. The slate lists the shot (based on the number established in the breakdown sheets) and take number, or the number of times the shot has been recorded, beginning with take 1. The editorial team will use the sound and synchronize it with the physical action of the stick coming down to “sync up” each reel. In the vernacular of filmmaking, a reel that has been synced is said to have been “sunk.”

FAST MOTION

FAST MOTION

Fast motion, or time-lapse, is created by shooting fewer frames per second, or running the film through the camera more slowly (also known as “undercranking”). When the images are projected at normal speed, the action appears to move faster than normal.

ACTION STEPS

Using a Film Camera

A film camera functions in much the same way as a digital camera, with the important difference being that it captures imagery on physical film instead of digital ones and zeros. If you’re using a film camera, your instructor will give you step-by-step instructions on how to load film into its magazine, the compartment that holds the film as it runs through the camera. After that, follow these steps and you’ll be ready to go:

Mount the camera on its base.

Mount the camera on its base. Load film into the magazine and thread it through the camera’s mechanism or gears.

Load film into the magazine and thread it through the camera’s mechanism or gears. Mount the film magazine on the camera.

Mount the film magazine on the camera. Select your lens and mount it.

Select your lens and mount it. Looking through the viewfinder, frame your shot.

Looking through the viewfinder, frame your shot. Using a light meter measure the light hitting the object or actor you are going to shoot (see Chapter 8), determine your aperture and shutter speed, and set them.

Using a light meter measure the light hitting the object or actor you are going to shoot (see Chapter 8), determine your aperture and shutter speed, and set them. Focus on your subject by dialing the focus ring. Measure your distance to the subject with a cloth tape, and use that measurement to get your focus near-perfect (the focus ring has distance markings).

Focus on your subject by dialing the focus ring. Measure your distance to the subject with a cloth tape, and use that measurement to get your focus near-perfect (the focus ring has distance markings). When you’re ready to shoot, start filming by turning the switch on. To stop filming, turn it off.

When you’re ready to shoot, start filming by turning the switch on. To stop filming, turn it off.