module 44 Nonchemical Water Pollution

502

When we think about water pollution, we most commonly envision scenes of dirty water contaminated with toxic chemicals. Though such scenarios certainly receive a great deal of public attention, there are other, less familiar types of water pollution. In this module, we will examine four types of nonchemical water pollution: solid waste, sediment, heat, and noise.

Learning Objectives

After reading this module you should be able to

identify the major sources of solid waste pollution.

explain the harmful effects of sediment pollution.

discuss the sources and consequences of thermal pollution.

understand the causes of noise pollution.

Solid waste pollution includes garbage and sludge

Solid waste consists of discarded materials that do not pose a toxic hazard to humans and other organisms. Much solid waste is what we call garbage and the sludge produced by sewage treatment plants. In the United States, solid waste is generally disposed of in landfills, but in some cases it is dumped into bodies of water and can later wash up on coastal beaches. In 1997, scientists discovered a large area of solid waste, composed mostly of discarded plastics, floating in the North Pacific. This area, named the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, appears to collect much of the solid waste that is dumped into waters and concentrates it in the middle of the rotating currents in an area the size of Texas. Other ocean currents appear to also have the ability to concentrate garbage. Given the vastness of these areas, no one is certain how much solid waste is floating but current estimates are in the range of hundreds of millions of kilograms.

Garbage on beaches and in the ocean is not only unsightly; it is dangerous to both marine organisms and people. Plastic rings from beverage six-

503

Another major source of solid waste pollution is the coal ash and coal slag that remain behind when coal is burned. As we saw in Chapter 12, such waste contains a number of harmful chemicals including mercury, arsenic, and lead. The solid waste products from burning coal are typically dumped into landfills, ponds, or abandoned mines where it can contaminate groundwater. In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency considers the waste from burning coal and other fossil fuels to be “special waste” that is exempt from federal regulations for the disposal of hazardous waste. In addition, most states have either no regulations or weak regulations governing the disposal of coal ash and coal slag.

Sediment pollution consists of soil particles that are carried downstream

As noted in the our discussion of the Chesapeake Bay, sediments are particles of sand, silt, and clay carried by moving water in streams and rivers that eventually settle out in another location where water movement is slowed, such as where streams empty into lakes and rivers empty into oceans forming deltas. The transport of sediments by streams and rivers is a natural phenomenon, but sediment pollution is the result of human activities that can substantially increase the amount of sediment entering natural waterways (FIGURE 44.2).

Numerous human activities lead to increased sedimentation. Construction of buildings, for example, requires digging up the soil, and the bare ground can lose some of its soil to erosion. As we saw in Chapters 8 and 10, plowed agricultural fields are susceptible to erosion from rain and wind. Sediments can also enter streams and rivers when natural vegetation is removed from the edge of a water body and replaced with either crops or domesticated animals that continually disturb the soil when they come to drink. According to recent estimates, 30 percent of all sediments in our waterways comes from natural sources while 70 percent comes from human activities.

What is the effect of increased sediment caused by human activities? Perhaps the most noticeable is that waterways become brown and cloudy due to the suspension of soil particles in the water. Increased sediment in the water column reduces the infiltration of sunlight, which can reduce the productivity of aquatic plants and algae. Because sediments can also clog gills, they sometimes hinder the ability of fish and other aquatic organisms to obtain oxygen. In locations where water moves slowly, the sediments settle out and accumulate on the bottom of the water body. This accumulation can clog the gills of bottom dwellers such as oysters or clams. Since the sediments can contain nutrients, this pollution may also contribute to increased nutrients coming into the ecosystem. In total, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that sediment pollution costs $16 billion annually in environmental damage.

Thermal pollution causes substantial changes in water temperatures

Thermal pollution Nonchemical water pollution that occurs when human activities cause a substantial change in the temperature of water.

A third type of nonchemical water pollution, thermal pollution, occurs when human activities cause a substantial change in the temperature of water. Thermal pollution is most common when an industry removes cold water from a natural supply, uses it to absorb heat that is generated in a manufacturing process, and returns the heated water back to the natural supply. For example, we saw in Chapter 12 that electric power plants use nearly half of all water extracted; they remove cold water from rivers, lakes, or oceans, cool the steam converted from water back into water, and then return the water to nature at temperatures that are 10°C to 15°C (18°F–

Thermal shock A dramatic change in water temperature that can kill organisms.

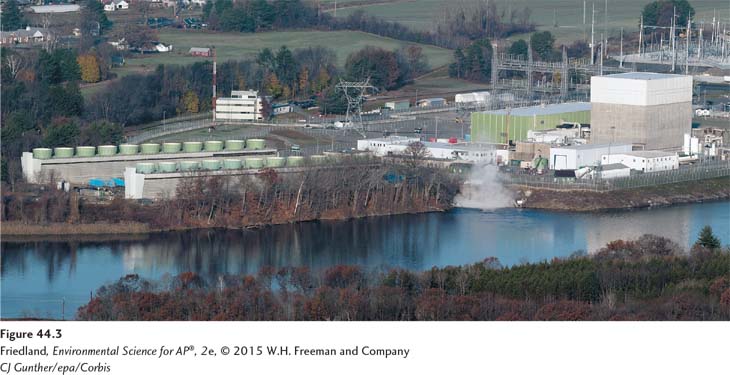

Species in a given community are generally adapted to a particular natural range of temperatures. Therefore a dramatic change in temperature can kill many species, a phenomenon called thermal shock. High temperatures also cause organisms to increase their respiration rate. But because warmer water does not contain as much dissolved oxygen as cold water, an increase in respiration and a decrease in oxygen will cause many animals to suffocate. In recent years, steps have been taken to help reduce thermal pollution, including pumping the heated water into outdoor holding ponds where it can cool further before being pumped back into natural water bodies (FIGURE 44.3).

504

In the United States, the EPA regulates how much heated water can be returned to natural water bodies. Compliance can become a real challenge in the summer when high demand for electricity causes an increased demand for cooling water even though the water in rivers and lakes will then probably be at its lowest volume and at its highest temperature. One common solution to this problem has been the construction of cooling towers that release the excess heat into the atmosphere instead of into the water. A cooling tower relies on the cooling power of evaporation to reduce the temperature of the water, much as we depend on our own sweat and a breeze to cool ourselves on a hot day. Some industries have built closed systems in which they cool the hot water in a cooling tower and then recycle the water to be heated again. In this way, the industries do not extract water from natural water bodies, nor do they release any heated water back into nature.

Noise pollution may interfere with animal communication

It may strike you as odd to think of noise as a type of water pollution. Indeed, noise pollution has received the least amount of attention from environmental scientists and, as a result, we know the least about it. When we think of noise pollution, what often comes to mind is the sound of city traffic. However, noise pollution also occurs in the water. For example, sounds emitted by ships and submarines that interfere with animal communication are the major concern. Especially loud sonar could negatively affect species such as whales that rely on low-

In 2003 a federal judge rejected the U.S. Navy’s request to install a network of long-